AMONG A LINE OF TERRACE HOUSES in the Sydney neighbourhood of Stanmore, a shamrock green door offers a clue as to the art-filled residence we’re here to visit. It’s the home of contemporary Australian artist Jonny Niesche, which he shares with his wife, Amber, son, Monte, and dog, Panda. It’s Panda who greets us first, tail-wagging her way to the door to welcome us in. Shortly after, Niesche appears. He’s wearing black track pants and brown sneakers from Song for the Mute’s latest collaboration with Adidas, which he’s coordinated with a charcoal and black T-shirt from Bassike. That he’s colourmatched his outfit makes perfect sense: colour plays a starring role in the artist’s multidisciplinary practice.

“It’s kind of like having a soundtrack to paint to,” says the artist of the way the palette of an object or scene guides his compositions. “You choose a scheme and an idea that means something to you, you explore it, and you don’t know where it’s gonna take you. It’s a journey every time, which is really fun.”

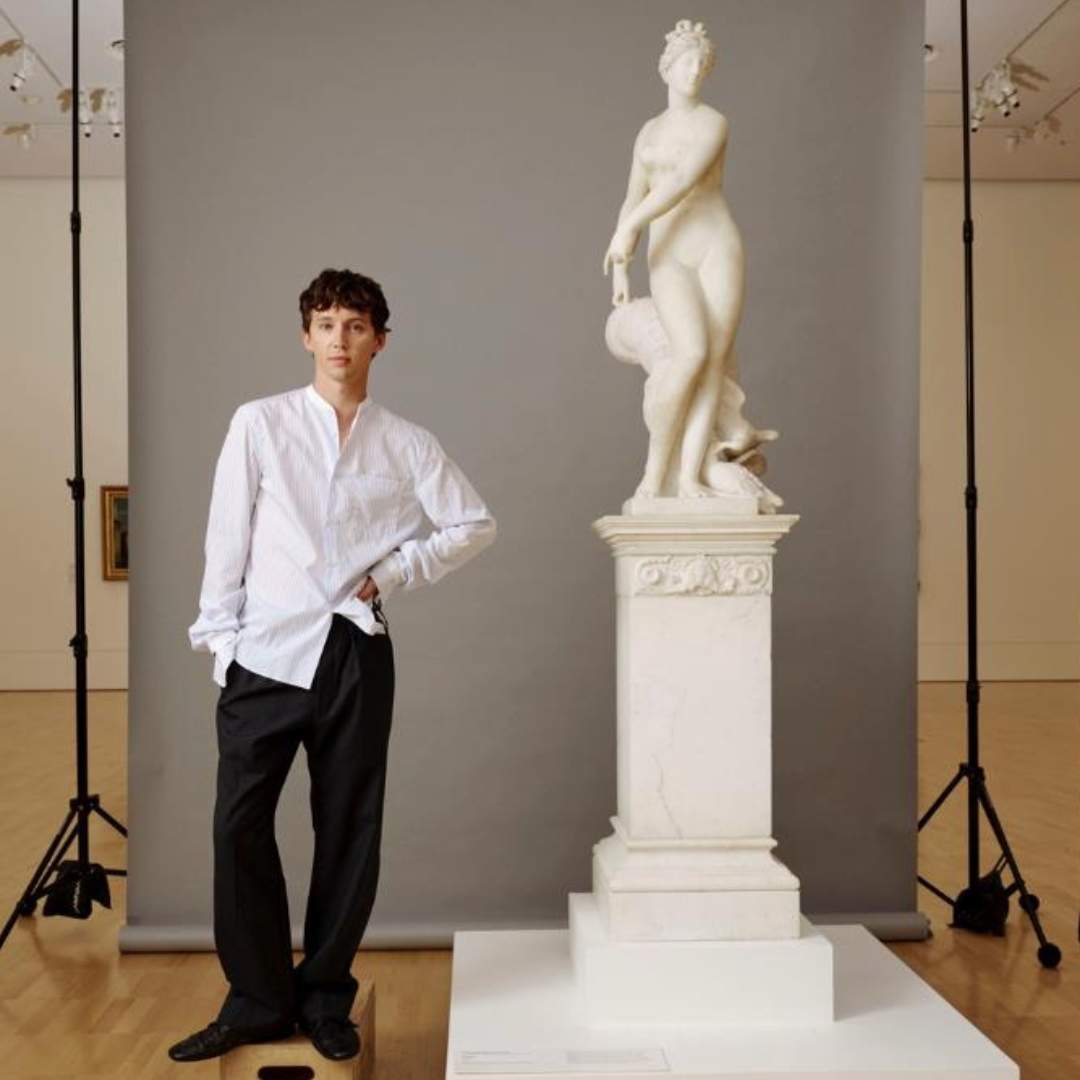

One of the most exciting names in contemporary Australian art right now, Niesche has exhibited all over the world, from Ibiza to Amsterdam to Germany, where he was the official artist for the 2024 Munich Opera Festival. Just this year, Gucci handpicked him to reimagine its iconic silk scarves and archival motifs as part of the Italian fashion house’s 90 x 90 project. His work is held in the collections of some of Australia’s biggest institutions, the NGV, MCA and MONA among them.

But we’re not here to talk only about the work Niesche makes. In addition to being a successful working artist, he is also an avid collector. The collection he and Amber have built, which brightens the walls, floors and surfaces of their two-storey home, contains some of the most significant names in contemporary Antipodean art. A Bill Henson photograph of a dark winding road is one of the first things you see when you walk through that green door and into the living room. A vibrant painting by Diena Georgetti from her recent The Collector collection hangs on the landing upstairs. Two photographs by renowned Māori artist Dr Fiona Pardington,

who will represent New Zealand at this year’s Venice Biennale, hang in the dining room. There’s a translucent piece by acclaimed sculptor Mikala Dwyer sitting in the living room, beneath one of Niesche’s own paintings, which he refers to as “image objects”.

“One of Monte’s friends came over and tried to sit on it the other day,” laughs the artist as he glances at Dwyer’s rockshaped work. “He was like, ‘Is this a seat?’ I was like, ‘No!’”

There are also a number of works by renowned German sculptors and painters, including a geometric painting by Gerold Miller and a light sculpture by Anselm Reyle. “He’s definitely one of my heroes,” says the artist of Reyle. “His way with colour, and the way he plays with cheap materials and turns them into something extraordinary, is really magical.”

This particular piece is made from mylar and found pieces of neon, which are encased in a Perspex box. It weighs about 100 kilograms. “When it was delivered to Australia it was broken, so I sent it back to Berlin, they fixed it and sent it back to Australia, and it was broken again,” laughs Niesche. “Luckily, I met this Australian guy who had worked in Anselm’s studio in Berlin, and he helped me put it back together, which was kind of cool, because it meant I could learn how they were made.”

Every art collector has a story of how they came to be a collector, as well as a method behind the works they collect. In a space that’s often associated with big purchases and art as investment, the combined story, process and ethos behind the Niesches’ collection stands out as unique. Rather than buying everything in their collection, most of the works he shows us have been traded with his contemporaries; artists he admires who, through the course of trading, have also become close friends.

“It started because I was working in studios next to other artists. You develop relationships and you admire someone else’s practice and you’re probably also very poor at the time,” he explains with a laugh. “But also, as time goes on, and you think more about art and the market and monetary transactions, there’s nothing more enjoyable to me than to think about trading with another artist that I admire. That way, it’s love for love, like for like, meaning for meaning. Rather than just, ‘Here’s my dollars, give me the work’.”

The first trade Niesche made was with Dwyer, who had supervised his master’s degree. When he graduated, she exchanged one of her trademark empty sculptures for one of his iridescent canvases, kickstarting a process that would transform Niesche’s future home into a rotating gallery of sorts.

“I’m swapping them around all the time. Amber and Monte will be doing something at home and I’ll be carrying paintings around like, ‘What about this over here?’” he laughs. “But I think things need to move around to regenerate and revitalise their energy.”

Niesche points to the painting by Gerold Miller. “If we were to move it over here, it would act differently. It responds differently to the environment around it, and it gives it life in a different way,” he says, gesturing hypothetically to the wall behind him where a Henson currently hangs. “I find that really exciting – creating different relationships between different works and seeing who talks to what and who hates each other. Because the thing is, today we’re hit with so many images all the time – on our phones, on the TV . . . and so they begin to become invisible to us. No matter how good a work is – and I’m sure some people will argue with me here – over time, hanging in the same place, it can become a bit invisible.”

The rotating aspect doesn’t just apply to their own home. The Niesches’ friends and family are also beneficiaries of the fact they don’t like keeping too much of their art in storage. One of Jonny’s best friends is currently babysitting a Bill Henson; his brother and sister-in-law have a few works on display, as do his parents.

“It’s really nice to keep them cycling around and getting them seen, rather than sticking them in storage where no one can enjoy them. I also think that by living with the work of someone who inspires you, you can just learn so much from it. When you’re lying on the couch, staring into space and you’re able to look at a fantastic work of art – that’s when ideas just kind of float around and come to mind.”

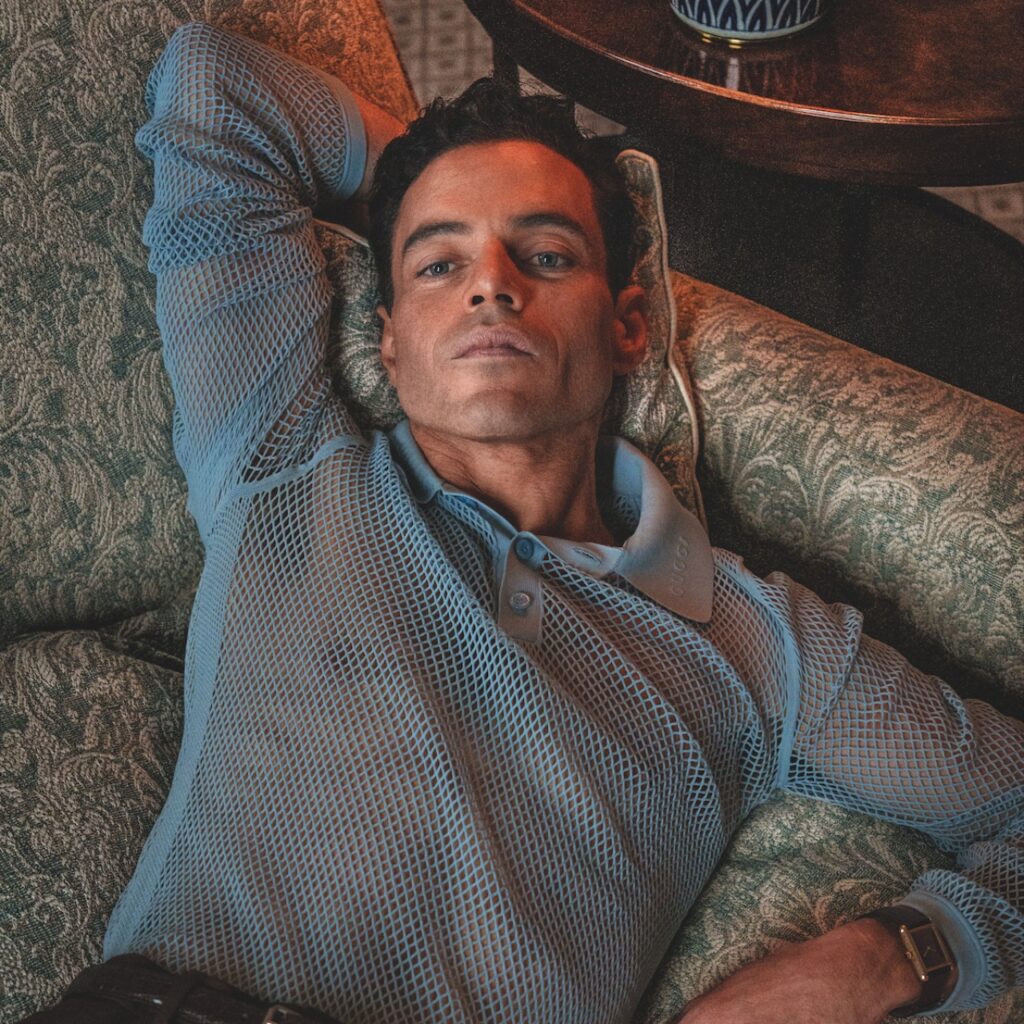

Of course, the inverse of Niesche’s trading philosophy is that some of the world’s most decorated contemporary artists also have his work hanging in their homes. Anselm Reyle, Fiona Pardington, Bill Henson, Gerold Miller, Robert Moreland, Diena Georgetti and American minimalist Vincent Szarek are all current custodians of a Jonny Niesche. “I love seeing where they hang my works, and what other artists they collect,” says Niesche as Panda, who has been hovering at a polite distance this entire time, comes looking for a pat. Nor is it difficult to see why such major artists – or anyone, really – would want a Jonny Niesche in their home. His works, which are constructed from voile that’s been sublimated with dye and wrapped around a mirrored frame, hum with colour. Because of their layered compositions, they don’t just hang in a space – they interact with it.

Rather than learning how to produce this sensation at art school, Niesche first got a feel for it in the recording studio – a decade making hardcore and experimental music in New York City might not have culminated in a record deal, but it did train him in the art of animating a room. “The studio is very much about placing sound in a sonic landscape. So, you’re thinking through sound, but you’re thinking about it sculpturally; you’re creating a whole field of sound that’s not just two-dimensional, or flat,” he explains. “That’s what I always found most exciting about music. So, for me, when I think about making my own art, I want to create something very spatial, and something that could hopefully lead you into some mystical, sublime distance with an element of magic.”

I want to create something very SPATIAL . . . that could hopefully lead you into some MYSTICAL, SUBLIME distance

Walking into the Niesches’ home does feel a bit like entering a parallel universe, one where a love of colour, form, light and music collide to create an eclectic haven, which explains why it was recently chosen to feature in Collecting: Living with Art, a book on the homes of Australia’s most prolific art collectors. As we make our way upstairs, Niesche points out a work by Lithuanian-born, Berlin-based Aistė Stancikaitė. It’s a cropped view of two gloved hands clasped in front of the creases of someone’s backside.

“Realism isn’t something Amber and I usually go for, but this one really spoke to us,” he says. “There was something quite saucy and sexy about it. It’s a little bit naughty, it’s a little bit demure, but it’s got some kind of magic, some otherworldliness to it that it’s abstract enough to be anything you want it to be, really.”

Back downstairs in the dining area, we gather around a large square table that was a wedding gift from Niesche’s dad. Above it hangs a gold chandelier that looks like it could be from the ’20s. “It was the one thing we decided to keep from the original house when we bought it,” he smiles. “It’s kind of kitschy, don’t you think?”

Niesche is enjoying a brief spell at home the day we meet him – the following day he’ll head to New Zealand to open his solo show, Fat Lava, at Auckland’s Starkwhite gallery. The heavy rust tones that make up many of the works are inspired by West German Art Pottery, a medium defined by thick glazes and oversaturated colours that Niesche used to find repulsive. “It’s the first time I’ve taken something that I wasn’t into, and found really uncomfortable, and tried to explore it,” he says of the colour palette. “But that’s what so much of being an artist is. You get this irksome feeling, and you just can’t let it go, so you’ve just gotta explore it. That’s where it took me.”

He has another solo show at 1301SW in Melbourne in August and, come September, will unveil an installation at Sydney Contemporary. Right now, he is also working on the biggest painting he’s ever made – for a private collector in Mexico. “It’s four metres by two metres,” he grins. “I think it’ll take up the whole side of a shipping container.” All the while, his home will play host to a rotating selection of artworks, its rooms evolving with every rehang and rearrange.

“My dream trade? Probably Mark Rothko,” says Niesche, adding that he’d have to coordinate that one with Rothko’s estate – the celebrated American artist passed away in 1970. “I would really love to live with a Mark Rothko painting, or a Donald Judd work.”

That justification contains the key to Niesche’s collecting theory, as well as how he intends his own art to be encountered: it is to be lived with, experienced and enjoyed from different vantages.

“It’s a really lucky position to be in – to have these works that you can just sit here and get nourishment from.”

This story appears in the Winter 2025 issue of Esquire Australia, on sale now. Find out where to buy the issue here.