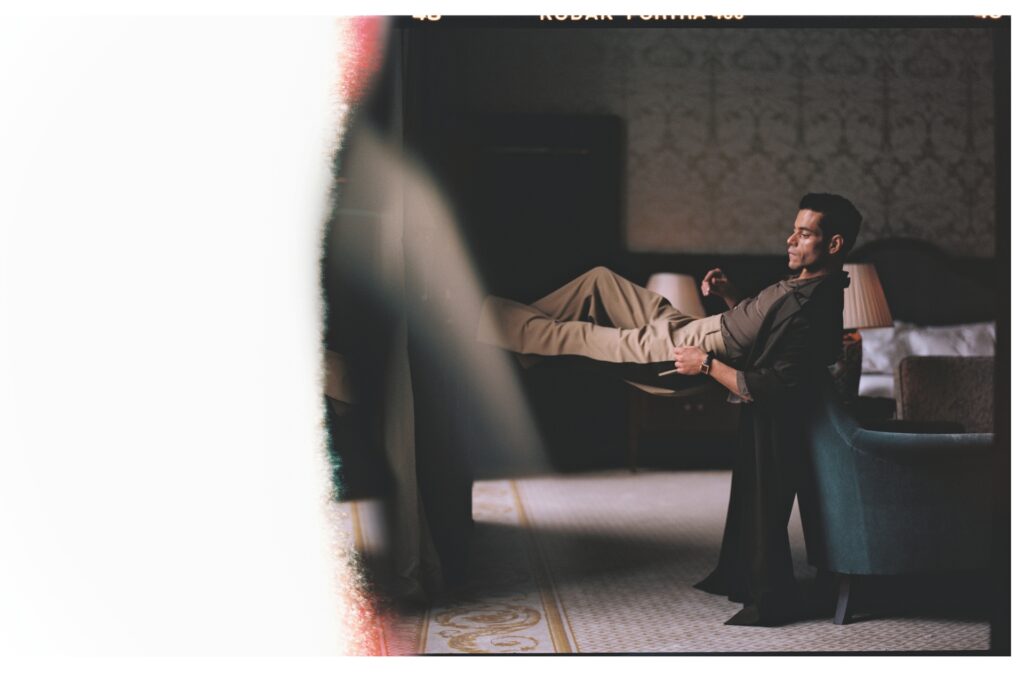

ONE THING YOU SHOULD KNOW about Rami Malek is that he has incredible core strength. I learned that the first time we met, in a suite at a West London hotel, where he casually balanced himself mid-air – feet resting on the edge of a wooden bureau, shoulders on the back of an armchair – like some kind of dashing human bridge. It’s no accident that Esquire is shooting Malek in the Haldane Suite, once the office of Richard Haldane, Britain’s first Secretary of War and a key figure in establishing MI5 and MI6. Because, as established as Rami Malek is, 2025 has been a year of pushing limits. In February, he made his UK stage debut at London’s Old Vic in his first return to theatre since he began his career acting in Off-Broadway plays in New York. This month, he steps into a new role as the first-time producer of The Amateur, a London-based spy thriller in which he plays a CIA decoder whose world shatters when his wife is killed in a terrorist attack.

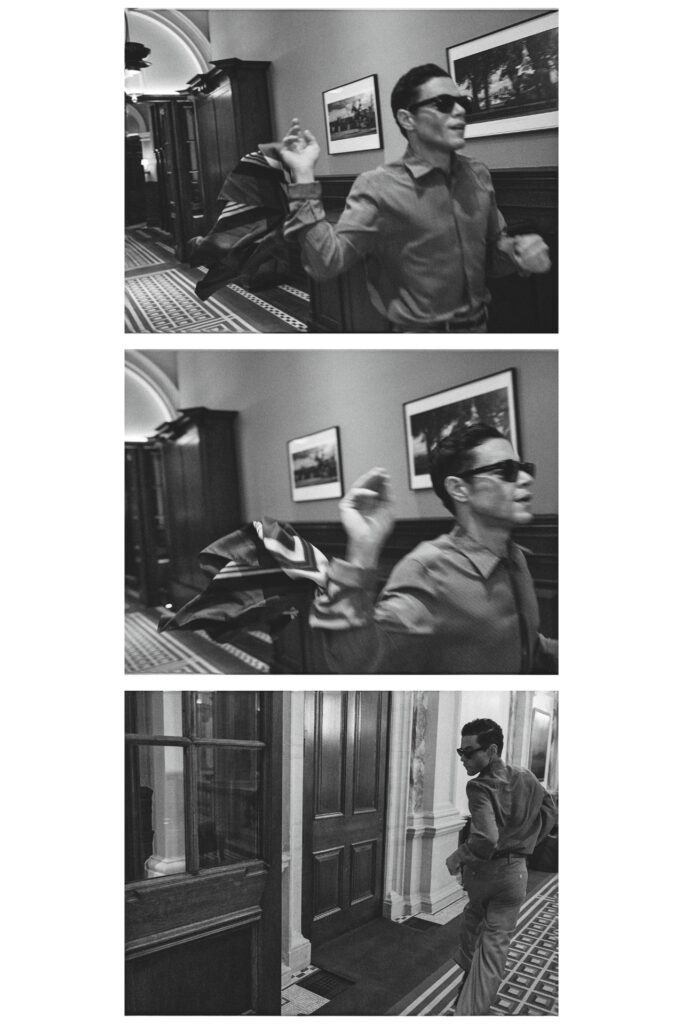

Proving his chops as an all-action leading man, Malek held that pose for what felt like forever, ensuring everyone got what they needed, before flinging himself into a new outfit in 30 seconds flat. By the time he has changed from a leather jacket into a silky shirt, I’ve realised exactly what kind of man Rami Malek is: someone who doesn’t do things by half measures. A man who has spent his entire life committing to the bit and shows no signs of stopping anytime soon.

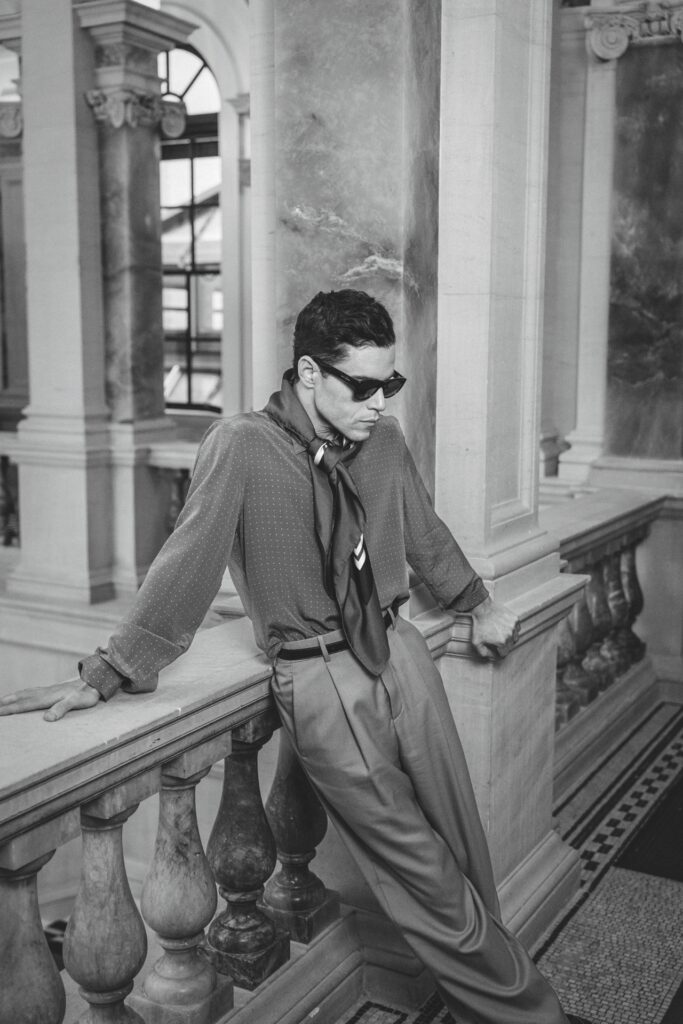

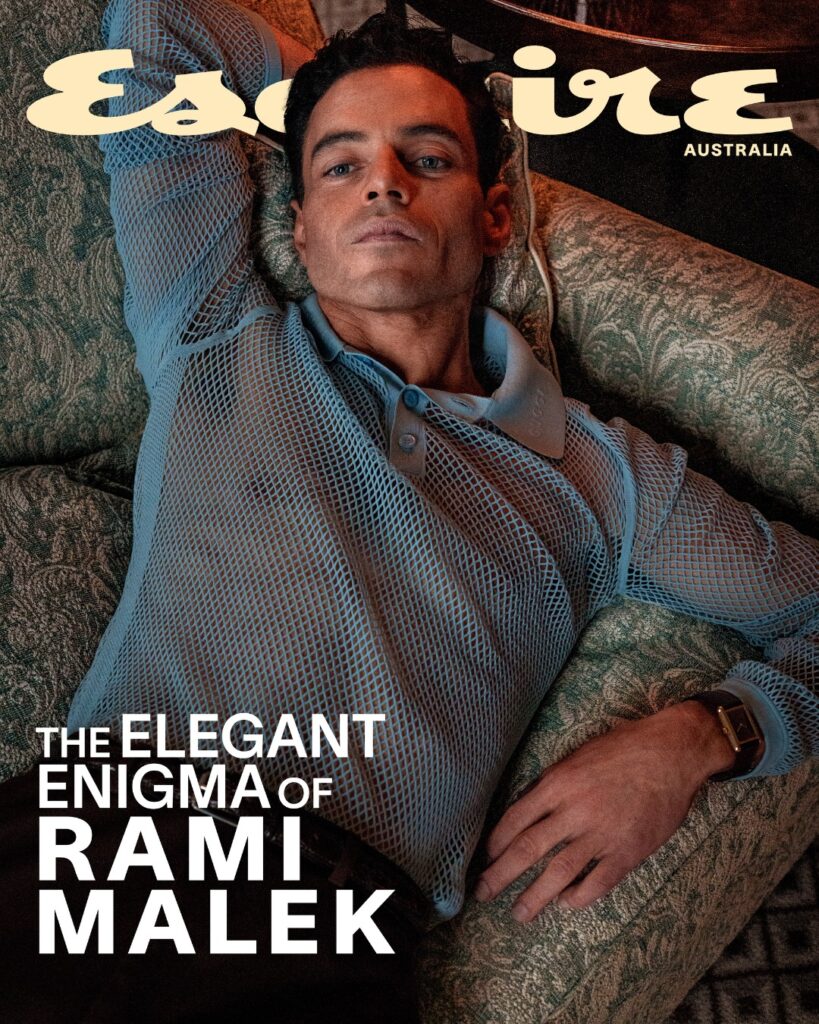

The photographer barks at Malek to be “more mysterious”. He obliges instantly. With his right leg suspended in a doorway, expensive sunglasses sitting flush on his nose, and the barest twitch of a muscle in his cut-glass jaw, he succeeds at making himself look just that. More mysterious – as if he’s got a secret to hide and there’s no chance in hell he’s letting you in on it. Don’t ask me how he does it. He’s built like a whippet and moves like a gymnast. There’s no wasted movement as Malek slinks around the room, folding himself over the furniture in couture. It’s easy to see why luxury fashion houses like Saint Laurent and Cartier have singled him out as one of their darlings. What wouldn’t look good draped on that wiry frame? What colour wouldn’t pop against those cornflower blue eyes?

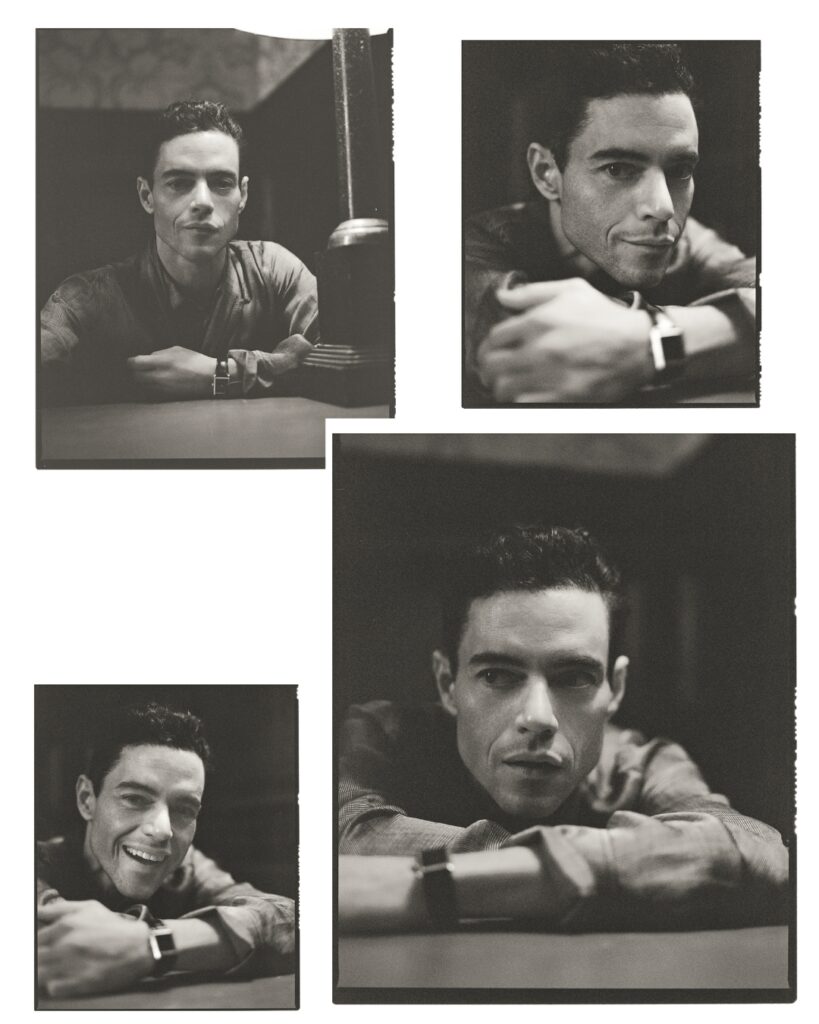

Even from across the room, when his eyes land on you it’s like getting hit by a wave. You feel drenched. Throughout the shoot, Malek had been standing and flitting – at one point even getting his hands on the camera – but then he finally sat down, as if suddenly aware he’d need to reserve some energy for later. He glided feather-like into a loveseat. But he could only sit still for a moment before he pulled himself to his feet again and moved on to the next outfit and pose. It’s exhausting just to watch.

Already an accomplished actor before his Oscar- winning portrayal of Freddie Mercury in 2018’s Bohemian Rhapsody, the Egyptian-American’s reputation as a character actor was built on powerful and nuanced performances as the enigmatic hacker Elliot Alderson in the critically acclaimed TV series Mr. Robot, before stepping into meaty supporting roles, firstly as Daniel Craig’s final 007-antagonist in No Time To Die, and later in Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer.

He’s not your prototypical leading man. There’s a hint of vaudeville about Malek – something Buster Keaton-y and balletic about how he can twist and contort himself on demand. He’s a natural-born performer with a magnetic charisma that comes through in his low Californian drawl. I’d go as far as to say no one looks or sounds quite like Rami Malek were it not for the existence of his twin brother, Sami. Born and raised in LA to parents who emigrated from Egypt in 1978, Rami and Sami’s first language was Arabic and they spoke it at home until the age of four. Although he describes his Arabic to Esquire as “not-so-brilliant” today, Malek’s voice remains a tool he’s in complete and utter control of.

Malek doesn’t mumble but speaks with quiet confidence, radiating so many kilowatts of charm during the shoot that it’s hard to believe he’ll have any left to perform on stage as Oedipus opposite Indira Varma’s Jocasta in Ella Hickson’s adaptation of the classic play – set to begin in as little as three hours. Switching from the headspace of a magazine photoshoot to an incest-riddled Greek tragedy isn’t easy, but neither is winning an Oscar or an Emmy. And Malek’s already done both of those.

“It’s a brave and brand-new world, I suppose,” says Malek, when we meet again in his dressing room at The Old Vic Theatre. “People ask me if it’s intimidating going out there in front of a thousand people. And for some reason, it’s not. I don’t find it that tricky or daunting. My favourite thing has always been collaborating with people at work. What I like is artists coming together and that communal experience of everybody sharing something and giving something that they’ve kind of treasured, cherished and discovered at the very depths of their soul – perhaps at some point in their life – and then having that all coalesce, either on stage or in front of a camera.”

Collaboration is something Malek takes seriously. He just as readily cites Tom Hanks, Amy Adams, Julia Roberts and Denzel Washington as inspirational colleagues as he does Jan Sewell, Pippa Woods, Maria Djurkovic, Eve Stewart, Newton Thomas Sigel and Dariusz Wolski – names that might not be as familiar but belong to the makeup designers, production designers and cinematographers who have helped bring Malek’s films to life.

The dressing room is cool and still. Permeated with centuries of history, it’s just the right amount of subterranean. You can watch Chelsea boots pounding the streets above through a series of frosted windows, safe in the knowledge you can look out at the world but the world can’t look in. Chubby bulbs dot a large vanity mirror behind Malek’s head, bathing the room in a warm, candle-like glow. Some might feel overawed by the prospect of treading the same boards as legendary sirs and dames like Laurence Olivier, Judi Dench and Maggie Smith but Malek, dressed down in a black knitted shirt and crisp blue trousers, appears at ease with the challenge.

“I just get here every day and feel like it’s a privilege to be out there at The Old Vic. It’s embedded in the cultural history, not only of this country but all over the world. I think this theatre resonates as a place that warrants a certain amount of respect.”

It’s easy to get caught up in Malek’s wonderfully meandering monologues, his train of thought gliding through conversation without the faintest screech of the rails before you realise he’s arrived at a completely different destination from where you thought you were going. He doesn’t speak in simple sentences but in lucid, fluid paragraphs. He’ll apologise for talking in “roundabout ways” yet even the way he takes those linguistic roundabouts – on the hard shoulder, pedal to the metal – comes across as sincerely profound. When Malek speaks, or rather purrs, he gives the impression of an outsider: an ironic description for someone with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. But Rami Malek is full of contradictions.

He’s a man who doesn’t like the spotlight, but thrives under it; a man whose face is often plastered across advertising boards but shuns social media; an LA-born movie star who prefers to live in leafy north London; and a man who has reached what most would deem to be the pinnacle of a career as a screen and TV actor, but is now pushing himself to perform on stage and produce films.

“I have never thought I was a made man,” says Malek, firmly. “I never have, and I don’t think I ever will. It’s just not in my bones. It’s not in my DNA. I have a strong drive to keep working on things that I am passionate about and elevating them. And if there’s something that I am incredibly passionate about I will reach for it with resolve and determination, with the same grit and fight that I had in my younger days, but I won’t let it engulf me in a way where it becomes detrimental. Because it can easily topple you.”

Something he’s set his drive to most recently is The Amateur. Starring big hitters like Laurence Fishburne and Jon Berthnal, as well as rising star Rachel Brosnahan, The Amateur is sort of what you’d expect to happen if Q from James Bond – a franchise Malek is well-acquainted with, having played Luystisfer Safin in 2021’s No Time To Die – went rogue. Malek plays the lead role with wide-eyed enthusiasm and there are plenty of car chases, gun fights and explosions rammed into its pacy two-hour runtime. Malek was inspired by the recent success of the John Wick franchise just as much as he was by the old conspiracy-theory films he loved as a kid. He references The Fugitive, the 1991 thriller that saw Tommy Lee Jones take home the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, as a lodestar – a standout from a genre which has become seemingly extinct.

“You could do that back then. Why did we lose that?” he asks, more to himself than to me. “Why did we give up on it?”

“I’m driven to tell the stories of PEOPLE WHO ARE UNIQUE and somehow UNDERESTIMATED and FORGOTTEN or MISCAST in society”

Directed by James Howes of Slow Horses fame, The Amateur is a refreshing callback to that fun and stylish brand of action film. It’s a bit Bourne, a touch Law Abiding Citizen, a dash Mission:Impossible, and exactly the type of film your dad would watch on the TV while standing in the living room. That being said, the sheer scale and sound of the set pieces make it a film worth seeing on the big screen.

At this point of our conversation, Malek leans forward on his chair, his elbows resting on his knees as if to punctuate the importance of what he’s about to say next. “Getting to work with those guys, it’s not lost on me how good I have it,” he tells Esquire. “I pulled out the Rolodex for The Amateur and Laurence, in particular, is a man I’ve always wanted to work with. I remember meeting him years ago with my twin brother and he reminded us both of our father. He was so reminiscent of my dad and I remember looking at my brother thinking: Is it just me or is something special going on there? So, to get that opportunity to have a Hollywood icon of that nature to be in a movie you’re producing and acting in is another pinch-yourself moment that I keep acknowledging and recognising.”

Acknowledgement and recognition are important therapy-speak traits for any Hollywood actor doing a press circuit. But surely a bit of genuine joy has got to come into it as well?

“I can levitate for a moment in the circumstance,” Malek admits, choosing his words with the care you’d use selecting a chocolate from a selection box, keen to avoid anything filled with raspberry liqueur, “but my feet are always very much tethered to the ground.” Like I said: sincerely profound.

Considering his lithe stature, you might think a man like Rami Malek sticks out next to beefcakes like Fishburne and Berthnal. You’d be right. But Malek is convincing as a man that no one expects to be dangerous. Unlike most action movie heroes, Charlie Heller flinches at explosions. He loses sleep over whether or not he’s doing the right thing. The film leans into Malek’s striking appearance and oddball demeanour, with the antagonists not taking him seriously until it’s too late. And by “too late”, I mean he’s already blown them up. Did I mention there are a lot of explosions in the film?

“I wanted to continue that idea of playing someone who is an outcast,” says Malek. “Someone who we don’t expect to do something extraordinary because I see that every day, day in and day out: people doing extraordinary things under extreme duress when they could easily fall into hopelessness and let all those stages of grief overwhelm them to the point where they become debilitated.”

He knows exactly how rare it is to be an action hero of Arab descent, and he carries that knowledge like a badge of honour. “It’s my blood. It’s where I’m from. I find myself speaking in Arabic to my mum in this dressing room and it’s interesting when people come in and discover that and go: ‘Oh, yeah, he comes from that world’. And I think that consistently surprises people, which is a shame.”

Malek’s heritage isn’t something he’s ever tried to hide – his mother once made a batch of baklava which he brought with him to an audition and, like any good Egyptian son, she was the first person he thanked after winning his Oscar – but following early typecasting that saw him pigeonholed in roles as an Iraqi insurgent and a suicide bomber, Malek held a caucus with his agents, refusing to take on any roles where he’d portray Arab or Middle Eastern characters in a negative light.

“It’s still a fight,” he adds. “It’s a profound fight and struggle and if I have to say that I can’t imagine what it’s like for the younger generation. Well, I can because I was there once. But I’m at an age now where I still have a passion for the things that I find an element of conviction in and things that I feel will help society and entertain them side-by-side in a mutual way that benefits us and moves us forward, culturally and in a progressive social way. So, if there’s some type of commentary that can be addressed sociopolitically as well that’s always enticing for me. I’m driven to tell the stories of people who are unique and somehow underestimated and forgotten or miscast in society.”

It’s about more than just the stories he tells on screen. Malek was recently at the British Parliament as a keynote speaker at the International Rescue Committee’s (IRC) 2025 Emergency Watchlist event. The IRC is an organisation that supports millions worldwide, including displaced people in developing countries, by promoting vaccinations, providing cash assistance in war-torn nations and supplying emergency food. Using his platform to help others – whether through being a role model to those looking to break into the industry or through his work as an ambassador for the IRC – Malek believes everyone should have the chance to seek a better future. “That’s something I want to do more of – visit the region [Egypt] in that capacity, not only as a tourist but go back home and lend a hand properly.”

Even as his Middle Eastern food delivery arrives, the minutes until ‘curtain up’ counting down, Malek doesn’t break eye contact. Not once. “I want to look back on

my work as a whole,” he says, looking me square in the eye, “and see that not only did it entertain but perhaps it imbued someone with a sense of strength or guidance or discovery that perhaps they didn’t know they had.”

Following The Amateur, he’ll play Lieutenant Colonel Douglas Kelley in James Vanderbilt’s Nuremberg, a historical drama about the Nuremberg trial. After that? Your guess is as good as mine. But it’s bound to be interesting. Rami Malek is at the peak of his powers, and instead of resting on his laurels, he’s calling all the shots. He’s looking forward, not back, because, as he tells Esquire, “You can only reminisce on things for so long before they get stale”. He’s always learning, always striving to do more. He’s on the phone with marketing and going on location scouts. He’s meeting with journalists minutes before going on stage. He’s at once a Hollywood leading man and a beloved outsider, fitting in just enough to stand apart. He’s doing a hell of a lot, seemingly all of the time.

And while it might seem impossible for anyone to balance so many things at once, it’s important to remember one thing about Rami Malek: he has incredible core strength.

Photography: JUANKR

Styling: Tanja Martin

More from the Winter 2025 issue: