IN 1998, AMERICAN hip-hop bible Vibe magazine published a now-infamous article titled ‘Racer X’. In it, journalist Kenneth Li painted a picture of a burgeoning underground scene that, having emerged in the backstreets and alleys of early ’90s LA, had since taken over streets and highways as far away as Manhattan: street racing. Everything about it was illegal and, in hindsight, tailor-made to appeal to the Limp Bizkit generation: the races took place on public roads, with thousands of dollars and even cars themselves changing hands on the outcome of a 10-second drag. Garages and tuning shops became hangout spots by day, while after sundown, drivers risked their own lives – and those of the unsuspecting public – in a nocturnal, nitrous oxide-soaked battle to rule the streets.

The true allure, however, lay in the cars themselves – not American muscle cars or even European exotics, but cheap, fun-to-drive and eminently customisable Japanese sports cars. Shipped across the Pacific and technically illegal to own, Japanese Domestic Market (JDM) cars became collectors’ items, and the basis of a nationwide underground movement. And while not every driver raced them, those who took to the streets did so with a bottomless appetite for risk, knowing that if the police showed up and chased them down, their cars would be seized on the spot and turned into scrap metal.

If reading this is making you feel nostalgic, it’s likely for one of two reasons: either you’re a street racer yourself, or (and much more likely) you’ve seen the film that Kenneth Li’s article inspired: The Fast and the Furious. While today the multi-billion-dollar action franchise spawned by the 2001 original trades on outlandish CGI sequences and a cast of high-profile action stars, for an entire generation of millennial petrolheads, The Fast and the Furious wasn’t just a formative cinematic experience; it sparked the beginning of a lifelong love affair with sports cars, a golden-hued, high-octane and unabashedly cheesy introduction into the world of street racing and tuning culture.

Likewise, the public perception of Japanese cars – seen broadly until then as cheap, reliable and utilitarian family runabouts – changed the second Vin Diesel’s fictional crew and their blacked-out Honda Civics launched into frame. Just as The Wild One made Marlon Brando’s Harley an icon 50 years earlier, The Fast and the Furious turned vehicles like the Nissan Skyline and Toyota Supra into countercultural symbols for an entire generation. For car culture as a whole, it’s been perhaps the century’s most defining statement so far.

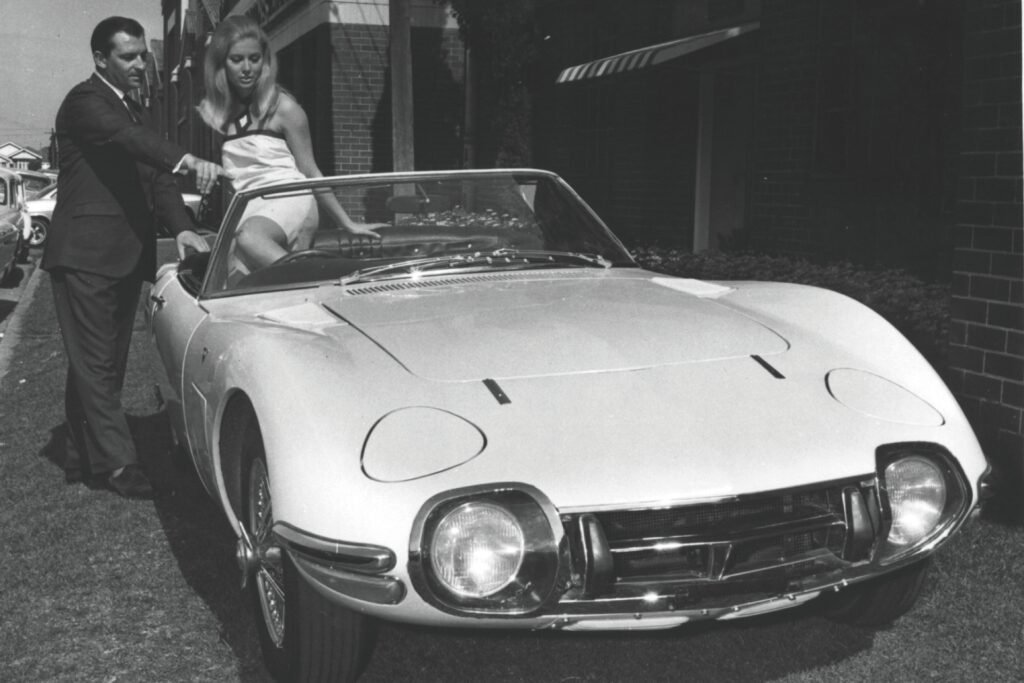

While it took until the turn of get their Hollywood moment, the aura of playful cool they enjoy today can be traced back more than half a century. The Toyota 2000GT, regarded as the nation’s first real supercar, permanently altered the West’s view of Japanese passenger cars when it debuted in 1967, earning a starring role in the Sean Connery-starring You Only Live Twice as Japanese agent Aki’s getaway vehicle of choice. Nissan brought its first two proper sports cars to Western roads two years later: the 240Z set a new benchmark for affordable, reliable performance, while the debut of the Skyline GT-R set the stage for an automotive icon, establishing immediate Japanese dominance on the global touring car circuit. Models like the Nissan Silvia, Mazda’s rotary-powered RX series and Toyota’s Celica would come to attract plaudits on streets and tracks alike throughout the ’70s – in comparison to traditional muscle cars, their smaller size, practicality and efficiency appealed to motorists hit by that decade’s oil crisis.

As Japan flourished socially and economically throughout the ’80s, so too did Western fascination with the nation’s culture and its cars. A sportier riff on the Toyota Celica, developed initially with the help of Lotus, would evolve into the affordable Porsche killer we know today simply as the Supra. Touge, a form of street racing popularised in the mountain roads around Tokyo and Osaka, emerged as the progenitor of the motorsport we now know as drifting, turning budgetconscious, ostensibly family-friendly cars like the Toyota Corolla and Honda Civic into underground icons in the process. After 15 years of dormancy, Nissan’s Skyline GT-R also returned in the form of the R32 (affectionately known as ‘Godzilla’), taking the world to task on the race track and proving so dominant in Australia’s own Touring Car Championship that after two years of embarrassing Holden and Ford in their own backyard (including successive victories at Bathurst), it was excluded from the competition in 1993.

“The public perception of Japanese cars changed the moment Vin Diesel’s crew and their blacked-out Honda Civics launched into frame”

But perhaps the most important thing anyone ever did to enhance the cool of Japanese cars was ban them. Introduced in 1988, Ronald Reagan’s Imported Vehicle Safety Compliance Act brought an end to the = importation of cars under 25 years old unless they were specifically intended for the American market or modified to comply with local regulations. By 1995, just 300 cars not intended for US dealerships were entering the country each year – down from 69,000 vehicles a decade earlier. Naturally, when American kids caught wind of an entirely foreign car culture flourishing across the Pacific, the cars they weren’t allowed to own became all the more desirable. As Subaru, Mitsubishi and Toyota waged a decade-long battle for dominance in the World Rally Championship, tuning magazines and anime series like Initial D brought an entirely new type of poster car to bedrooms across the West, replete with big wings, garish body kits and high-revving engines that buzzed and crackled like a hornet’s nest in a paint shaker.

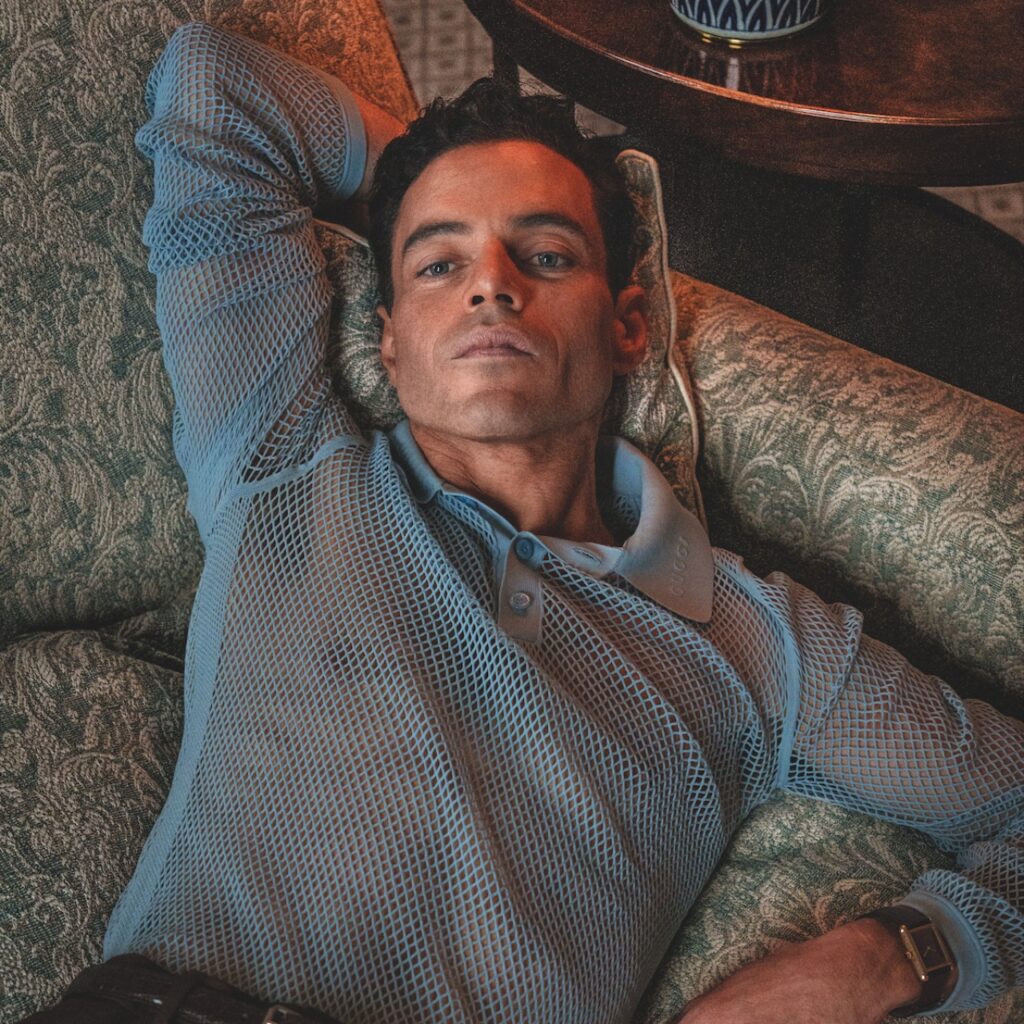

JDM vehicles became the new exotics for a new generation, a multi-million-dollar grey market of cars with aftermarket parts taking root as owners spent small fortunes to import, tune and ultimately race them – right under the nose of the authorities. All it took was Paul Walker, Vin Diesel and their band of mesh-singleted street racers to bring an already burgeoning underground scene fully into the mainstream.

Twenty-five years on from the height of the JDM craze, the automotive industry again finds itself at an era-defining crossroads. As the effects of global warming intensify, brands are scrambling to adapt to an environment defined by constantly shifting consumer sentiment and emissions targets that can change overnight with the stroke of a government pen. Meanwhile, spooked by sluggish sales of EVs at the premium end of the market, sports car icons like Porsche, Audi and Mercedes have spent the last few years committing to, and then shifting the goalposts of, a fully electrified future as they collectively attempt to define what the supercar of the 2030s will come to look like.

Japan, however, remains unshaken in its pursuit of fun, each of its most iconic car makers trawling through the archives in an arms race to reboot as many cult classics as they possibly can. Toyota’s Gazoo Racing division, responsible for both the company’s Le Mans and World Rally teams, has spent the last decade releasing totally bonkers, rally-derived versions of the Yaris, Corolla and even the Land Cruiser. Its long-awaited revival of the Supra, developed in a joint project with BMW, hit the streets to critical acclaim in 2018. Toyota isn’t the only Japanese marque reviving fun, relatively affordable sports cars for drivers to get excited about. Subaru’s WRX remains about the most fun you can have in a new car for under 60 grand. Honda brought back the NSX in 2020, and continues to set Nürburgring records with increasingly mad versions of the Civic Type R.

“The most important thing anyone ever did to enhance the cool of Japanese cars was to ban them”

There’s more on the way, as well. Toyota’s MR2 roadster is widely expected to be making a comeback in the next couple of years, while a redux of the Celica, inspired by the model’s World Rally dominance during the early ’90s, was unofficially confirmed by the company’s Chief Technology Officer back in January. Mazda has spent the last few years teasing concepts of a new, potentially rotary-powered RX sports car, and despite constant speculation surrounding the company’s financial troubles, Nissan remains defiantly committed to producing its GT-R sports car, as well as the recently revived Z coupe.

It’s behind the wheel of Nissan’s new Z Nismo that you get a proper feel for the undying appeal of Japan’s sports cars. A variant of the Z tuned by Nissan’s Nismo racing arm, it churns 310kW entirely through its rear wheels thanks to an upgraded twin-turbo V6, kicking up just enough wheelspin to put a goofy smile on your face if you’re feeling particularly playful when the traffic lights turn green. The chunkier body kit turns heads in the way you’d expect a supercar five times its price to. Sure, it’s decidedly more polished than the imports of old; there’s Apple CarPlay, a reverse camera and Alcantara seats. It runs off a nine-speed automatic. Expensive Bose speakers sit where an aftermarket Sony and a whopping great subwoofer might once have. But through it runs the undeniable DNA of the car so many 2000s kids grew up desiring. At a time when so much about the future is unknown, returning to nostalgic models that celebrate the pure emotion of driving is one big swing that’s cutting through.

Top image credit: Nissan GT-R 50th Anniversary, courtesy of Nissan

More from the Winter 2025 issue: