The rise of luxury clothing made specifically for the end of the world

Vollebak is among a vanguard of companies making clothes for the future, including puffer jackets built to survive the apocalypse

IT’S A GREY AND GUSTY morning in northern Iceland, and I’m in the backseat of an SUV hopping along one of Europe’s most dangerous roads. Árni Örvarsson, the driver, alerts us to a hairy bend up ahead, explaining that it is in fact sinking beneath us.

“The road is . . . sinking?” I ask, assuming he’s joking.

No, he is very serious. According to Örvarsson, thirty-one, the asphalt is sliding off the escarpment and into the frigid sea below at a rate of two meters a year. But he doesn’t seem to care because, he says, where we are going is worth the risk.

It’s May, and I have travelled to Akureyri, a town of fewer than twenty thousand souls just 60 kilometres south of the Arctic Circle, with Nick Tidball, cofounder of the British clothing brand Vollebak. The region is as beautifully desolate as it sounds. The looming walls of the valley send an eager wind whipping through town, over jagged rocks, and out across the fjord. Hardy seabirds circle high above, and the occasional whine of a prop engine drifts in the mist as planes wobble into the skinny airport. Here, the difference between spring, summer, and fall is meaningless. There is rain; there is sun; there is a sense that I am somewhere geologically uncertain.

Why am I here? To look at eiderdown, an arctic duck’s natural insulation. This is the material inside a popular and expensive jacket from Vollebak, a brand that is emblematic of an emerging trend in the world of men’s fashion: science-fiction clothing. The optimists, who are among my fellow passengers, will say the trend embraces a brighter future for us humans. But there’s also a menacing side to it: Many of the garments, which are very expensive, are marketed for the end of earthbound civilisation.

Call it dystopian chic.

Last year, the luxury industry was estimated to be worth more than $617 billion worldwide. And what, exactly, does luxury mean? According to the 2009 book The Luxury Strategy, by Vincent Bastien and Jean-Noël Kapferer, it is a product whose value is determined not only by its high-quality craftsmanship and exclusivity but also by its desirability. Consumers desire luxury goods because they elicit a certain emotion in them, for which they’re willing to pay top dollar.

Watches, clothes, and high-end spirits have helped drive the industry to dizzying heights, but nowadays the idea of luxury is being redefined. In an age of big tech, global unrest, and resource insecurity, more abstract luxuries have emerged. Time is a luxury; health is a luxury; arctic-duck insulation is a luxury; and repelling wild-eyed raiders trying to steal your water supply might be a luxury, too.

Vollebak makes what it calls “clothes from the future.” The items exist somewhere between rugged workwear, move-fast-and-break-things tech, and thought experiment. The brand is among a vanguard of clothing makers using cutting-edge materials to fuse garments with wearable tech.

“Time is a luxury; health is a luxury; and repelling wild-eyed raiders trying to steal your water supply might be a luxury too.”

Some of it you can buy now. For instance, both Vollebak and the British running brand Soar are making clothing using graphene, the lightest, strongest material ever created. Other garments are still in the experimental or even theoretical phase. Researchers in China claim to have invented a soft, washable fibre that can conduct electricity and transmit light, which means images could be displayed anywhere on a garment’s surface. Other scientists are developing a fibre-sized lithium-ion battery that could help make such wearable electronics practical. At MIT, researchers unveiled a close-fitting fabric that can sense movement and motion on the body, which they say could revolutionise sport science and video-game interfaces.

And a couple months ago, former Apple design guru Jony Ive teamed up with ChatGPT creator Sam Altman to eventually launch a wearable AI companion to rival phones, tablets, and smartwatches. The partnership represents a potential watershed moment: the terrifying, diffuse potential of AI meeting the intuitive usability of Ive’s real-world design.

All of this points to a brave new world for fashion – getting dressed for Tomorrowland. But many of Vollebak’s products are marketed less for a Disney-approved future and more for that of Mad Max. In 2016, the brand introduced a hoodie designed to help you de-stress. It was cast in a bubblegum shade of pink that’s clinically proven to activate your parasympathetic nervous system and calm you down. The walls of correctional facilities are painted in the same colour. The hoodie featured a fully closable visor with vents for nose breathing and pockets that allowed wearers to hug themselves to tranquillity. (You might have seen Jimmy Fallon and comedian Jon Glaser testing it out on The Tonight Show.)

The clothes, or at least how they were marketed, got weirder: An “Indestructible” field jacket made from Dyneema, an antiballistic fabric that’s fifteen times as strong as steel. A cozy hoodie and sweatpants that are fire-resistant, water-repellent, and windproof. A “virus-killing” coat made with copper that will supposedly neutralise any germ that lands on its surface. An Apocalypse jacket, which wryly promised to help its wearer survive a zombie invasion.

In late 2023, Vollebak released the Martian jacket. It is cut from the same type of parachute fabric used to land the Perseverancerover on Mars in 2021 and lined with aerogel, a superlight insulation that is 99 per cent air and will keep the next Mars rover safe while it explores the Red Planet.

Vollebak markets the jacket as post-Earth wear.

So what do Arctic ducks have to do with this?

In 2023, Vollebak released ten simple puffer jackets stuffed with eiderdown, priced at more than $6,000 apiece. They sold out instantly. The next winter, the collection expanded to twenty pieces. They sold out instantly. This year, Vollebak will make forty-five eiderdown jackets, ranging from $6,945 to $11,570. The presale is already closed.

Árni Örvarsson is not only our driver in Iceland but also a former professional soccer player who now runs his in-laws’ third-generation eiderdown business. He is driving Nick Tidball and me to an eider-duck sanctuary, a thin sliver of delta on the seaward edge of the Troll Peninsula. Every spring, around forty-five hundred pairs of birds retreat from life on the arctic seas and settle in for a month of nesting and parenthood before heading back out to the rolling ocean once again.

When the ducks go, they leave a landscape dotted with nests, each lined with a few tufts of down weighing about an ounce combined, which Örvarsson and his family then gather, process, and sell on the global market as filling for winter coats, comforters, and more. Half goes to companies such as Vollebak and the rest is used to make their own line of products. A similar process happens across Iceland, which exports around three tons of eiderdown each year, roughly 75 per cent of the total global resource. Eider ducks have been protected all year round in Iceland since the 1850s, the only country to do so, Örvarsson explains. “Icelanders were starving,” he says. “We were just trying to survive. We lived in turf houses and ate potatoes. But still we had the guts to protect the eiderdown, because we saw the value of it.”

Eiderdown is the warmest, lightest, and quite possibly rarest natural down on the planet. Unlike goose and regular old duck down – which are by-products of the meat industry – eiderdown has microscopic fronds pitted with little hooks that cling together to create a near-weightless, hydrophobic web that traps warm air and repels water. It is the insulation of the gods and, predominantly, the superrich: A king-sized, dense fill comforter might set you back at least $23,000. In early 2022, Örvarsson cold-emailed Vollebak asking if the company would be interested in using his product in their collection. The email piqued Tidball’s interest, which eventually led to the creation of the jackets.

Tidball invited me to come see the annual Eiderdown collection. So here I am, at the edge of the world, on one of Europe’s most dangerous roads, to look at eiderdown nests – the latest element of sci-fi fashion.

Vollebak is the invention of brothers Nick and Steve Tidball, who started the brand in 2016 after working as advertising creatives. The duo specialised in marketing stunts, most notably in 2015, when they floated a full-sized house down the River Thames to promote a then-nascent Airbnb.

Nick Tidball is the quintessential big-picture guy, making constant reference to iconic creatives he hopes to emulate: architect Bjarke Ingels, chef René Redzepi, producer Rick Rubin, fashion designer Miuccia Prada, and composers Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Ludwig van Beethoven. He told me he wants to “write symphonies” with the company. I ask him if Vollebak is a fashion brand. “A ‘fashion’ brand?” he replies, grinning. “Fuck knows . . .”

In a 2020 interview with the Financial Times, Steve Tidball noted that Elon Musk was right about humanity’s future. “We are going to become a multi-planetary species,” he said, “and so we’re trying to advance toward intelligent clothing, because clothes will be used to make you faster, stronger, live longer, deliver medicines to your body. It’s just an absolute inevitability.” (Nick Tidball mentions Musk just once in Iceland, referring to a time when he was “more normal.”)

For much of its nine years in business, Vollebak has considered itself a disrupter, catering to a market of men, largely, who are interested in either tech and the scientific endeavour of a plucky, investment-backed start-up or the real-world capabilities of its clothing, or both. Nick Tidball says that around 50 per cent of the Vollebak customer base comprises high-net-worth individuals, but what unites all the customers, he adds, is “intellectual curiosity.” They’re not necessarily style guys, but maybe they follow the markets, he says, or listen to cult podcaster Lex Fridman. “It’s their job as a good human to know a lot of stuff.”

But as I suggest to Tidball, among all the techy, big-picture talk, there is an end-of-days undertone to Vollebak.

Several companies are already making clothes that might, in theory, outfit someone for the apocalypse. There’s a reason Mad Max wore leather; it’s practically indestructible if a tad . . . sweaty. Brands like Stone Island and C.P. Company have made tough technical garments with cutting-edge materials for decades. Even high-quality cashmere would prove a lasting material; Loro Piana, for instance, has made water-repellent cashmere items for decades. But whether it’s leather outfitters or straightforward luxury brands, these names don’t market their clothes for a nuclear winter.

Given the state of the world – climate-induced disasters, pandemics, war, general uncertainty – selling clothes with an end-of-times vibe seems potentially lucrative. Recent FEMA data shows that almost twenty million Americans, around 7 per cent of the population, consider themselves preppers, that is, people taking steps to prepare for massive national or global unrest. And in turn, the so-called prepper industry is expected to be worth US$2.46 billion in the next five years. I ask Nick Tidball whether a landscape of future insecurity is good for Vollebak.

“Yes,” he says, “but I would see it in a different way. I see it as an opportunity to create change as opposed to an insecurity of what’s going to happen. Instead of being nervous about the future, which I’m simply not,” he adds, “I see endless opportunities. And there’s endless things happening in material technology that are being completely underexploited.”

Eiderdown is not a space-age material – in fact, the Icelandic tradition of gathering it can be traced to the 1300s and possibly as far back as the Vikings – but its performance and rarity appealed to the Tidball brothers. The eiderdown jacket is relatively simple compared with anti-pandemic wear or zombie-proof jackets, and it represents the brand’s foray into straightforward luxury. The standard-issue hedge-fund manager in New York or Geneva might not be interested in a T-shirt that biodegrades or a jacket reinforced with 5.5 kilometres of “meta-aramid” thread, but he’d likely be into this. Is Nick Tidball concerned that embracing eiderdown might conflict with the brand’s future-facing shtick?

“Nature, technically, is the ultimate technology,” he says, adding that he likes how Vollebak can “zig and zag” in search of the best-performing garments and materials. He likens it to the career of Pablo Picasso. “He could have just stopped at ‘I’m a really good portrait painter and I’m eighteen and I can paint portraits better than anyone who’s ever lived,’ but he didn’t.”

“Vollebak shoppers aren’t necessarily style guys, but maybe they follow the markets or listen to cult podcaster Lex Fridman. “It’s their job as a good human to know a lot of stuff.”

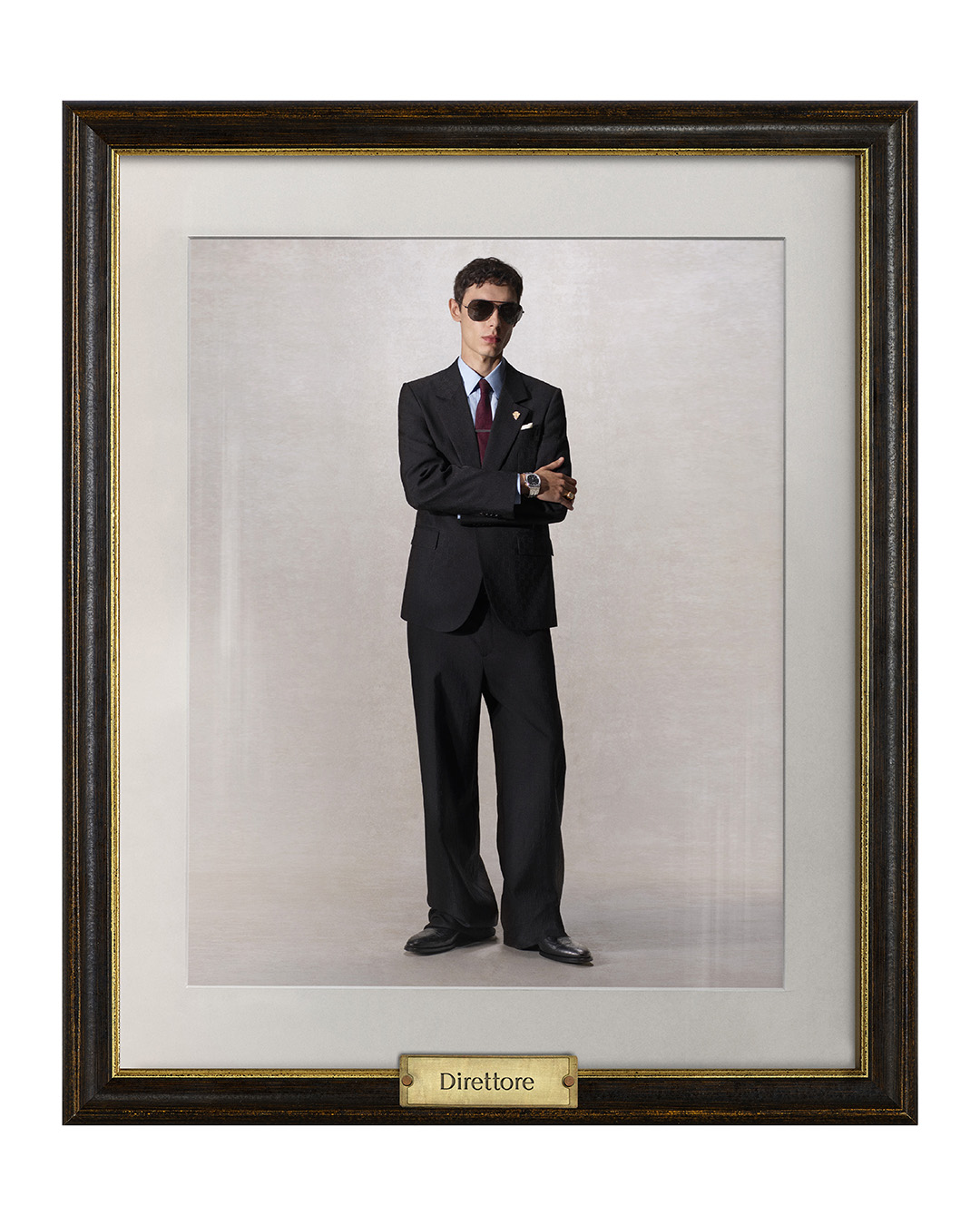

Vollebak’s most popular product is a two-piece travel suit that costs $1,681. Available in black and navy blue, it’s as simple as tailoring gets: slim lapels, a single vent in the back, and lined with a regenerated-cellulose cupro fabric woven in northern Italy. But the suit is stretchy, water-repellent, and abrasion resistant, and it’s “embedded with zinc-based antimicrobial technology that kills bacteria to combat sweat,” according to the company. Similar designs are available elsewhere. Japanese outdoor brand Snow Peak has a water-repellent stretch suit, as does Veilance, the ascetic offshoot of outdoor brand Arc’teryx. Even Uniqlo has one, and it’s just over a hundred bucks.

But the Vollebak suit has the virtue of coming from a brand that’s aggressively marketed itself as not simply functional but ideal for our interesting times – and whatever might come next.

On Vollebak’s subreddit platform (always a signifier of cult status), one biker likes the brand’s “Indestructible” pants because they have a higher per centage of Dyneema than “most motorcycle jeans on the market,” while another guy says the Apocalypse jacket is great for traveling light because the pockets have space for balled-up socks that he can’t fit in his bag and the ammo straps on the chest are good for holding sunglasses. (We can assume he’ll update the review if and when the zombie apocalypse gets going.)

The Eiderdown collection has a tougher time of it on the forum. One poster says he bought one of the original releases in 2023. “It’s an amazing lightweight piece,” he says. “I don’t wear it daily. For daily wear I go with either Indestructible Puffer or the Aerogel Puffer.” Most guys say they love it, but it’s just too pricey. “I’d love one,” says u/we32, “but yikes.”

Perhaps the notion of a centuries-old form of natural insulation simply isn’t progressive enough. Or maybe it needs to be marketed as a jacket that will survive an alien invasion.

Back on the Troll Peninsula, we have reached the eider sanctuary. It sits in a topographic cradle, flanked by a vast, mountain-rimmed lake to one side and the open ocean to the other. The sky is huge, and great storm clouds collect just inland, glowering at the clear, sunlit vista that holds out over the sea. The eider ducks litter the pebble beach, their nests wedged into old tires and tufts of seagrass wherever you look. The only sounds are the lapping of the millpond waters and the gentle cooing of the birds themselves. After a wander around, Örvarsson suggests we all lie down and close our eyes to let the unyielding tranquillity of the scene envelop us. “Perks of the job,” he says.

As we lie there, I think not just of how impossibly beautiful this place is, and how lucky I am to be here, and how the upward inflection of the ducks’ coo makes them sound like they’ve just seen a sweet treat. I think that if things were to go belly-up back home, this would be a great place to see out the apocalypse.

At least I know we’d be warm.

This story originally appeared on Esquire US.

Related:

The best jean’s for men to buy in 2025

Austin Butler’s Caught Stealing puma’s should be on your rotation