A maverick’s modern art collection, according to Thomas Demand

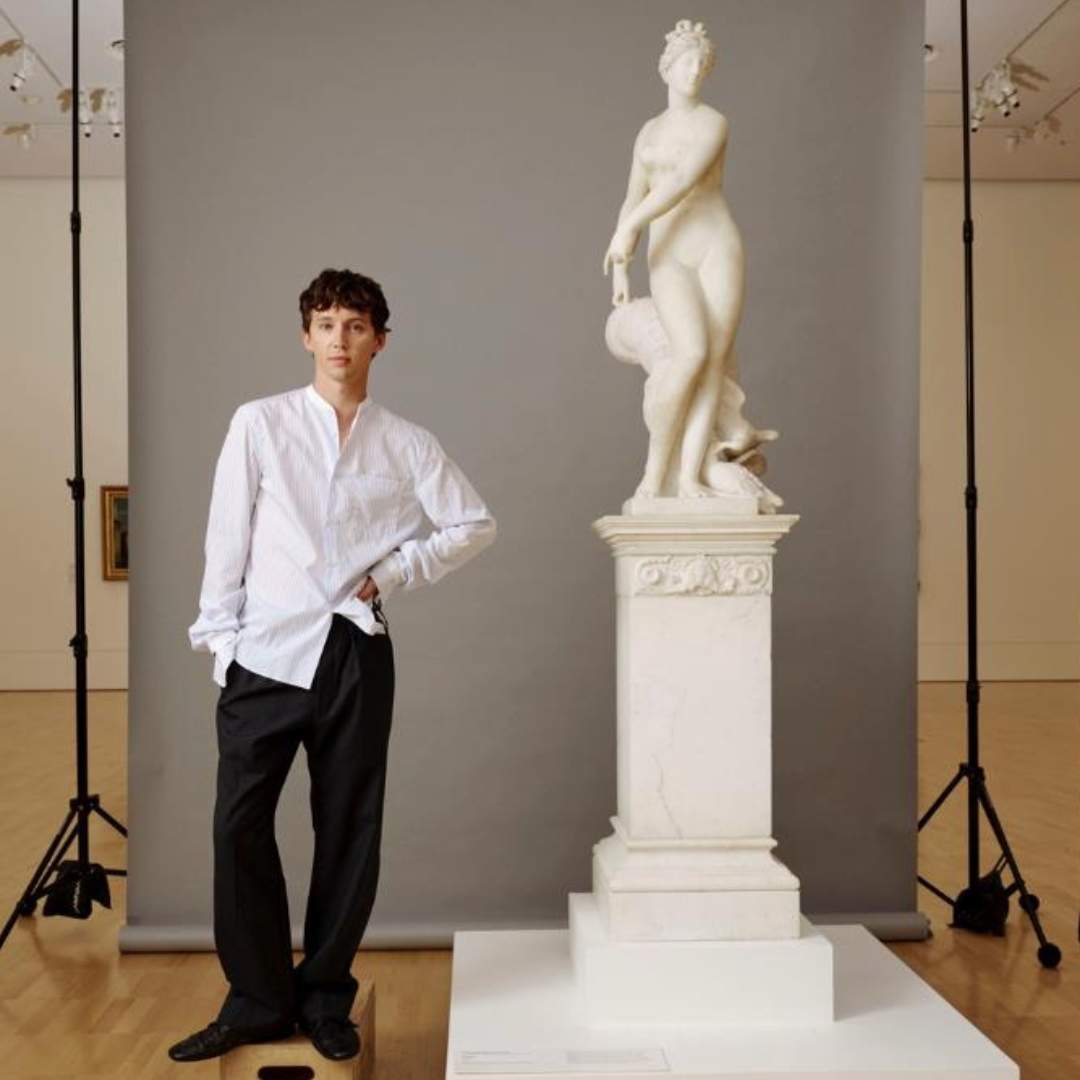

With ‘The Object Lesson’, the German sculptor and photographer plays curator and exhibition designer of the AGNSW Kaldor art collection

THOMAS DEMAND hates your silly socks. The German artist thought he could pick up a few extra pairs during his brief trip to Sydney, but all David Jones could offer were football to fish printed polyblend. “It’s ridiculous. You look around the [Sydney] marathon and you see everyone in short pants and those socks, and you realise it’s a communicative tool,” he says. “These grown-ups in their stupid, silly socks.” The socks Demand wears are an elegant, ribless pair in orange that pop from beneath his white jeans as we walk through The Object Lesson, his new Kaldor Public Art Project at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW).

Communicative tools are important to Demand, 61, who began his career as a sculptor but then started photographing his life-size paper and cardboard models constructed to depict quotidian and political scenes. Unlike his body of work, The Dailies, which was presented in the mushroom Harry Siedler building on Martin Place for his first Kaldor project in 2012, Demand isn’t the focus of The Object Lesson.

For nearly six decades, veteran arts patron John Kaldor has invited some of the biggest names in contemporary art to Australia under his namesake public art project. The first was in 1969 when he commissioned artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude to wrap the Little Bay coastline in the now legendary Wrapped Coast project. Others include Jeff Koons’ towering puppy sculpted out of live flowering plants on the Tallawoladah Lawn in 1995; Marina Abramović’s “brain spa” at Pier 2/3 in 2015, where the Serbian performance artist hosted audiences to sit across each other in a similar set up to her monumental 2010 piece, The Artist is Present.

For the latest and 38th project, AGNSW director Maud Page proposed that Kaldor reshow some of the 260 works of modern and contemporary art that he gifted the museum back in 2008. Worth $35 million, it was the biggest of any other Australian donor at the time. “My first reaction was, ‘Thank you, but I don’t want to have another collection exhibition. I want to turn an exhibition into a project’,” says Kaldor, “it was only until [AGNSW senior curator] Nick Chambers and I decided we needed the eyes of an artist.”

A friend and avid collector of Demand’s since the ’90s, Kaldor enlisted the German artist to select some 70 artworks for the project. To put a face to the endowment, Demand mounted a portrait of Kaldor by photographer Albrecht Fuchs at the entrance of The Object Lesson. Kaldor, 89, voted against it, but Demand reasoned that it was to put “an emphasis on the person who collected these artworks, for whom art is more than an investment or a social instrument, and who took a risk to get a hold of these works and bring them to Australia.”

When I meet Demand on a sunny Friday morning, slightly tired after a week of overseeing the exhibition’s final touches, he’s generous and wryly funny, speaking earnestly about the task. A nearby PR rep approaches with a glass bottle of water for him, then asks what I’d like. I’ll have the same. When she leaves, he insists I have his.

Demand describes his role in The Object Lesson as a “circus director”, assembling headlining acts like Frank Stella, Richard Prince, George & Gilbert, Francis Alÿs, Nam June Paik, and more, many of whom the megastar artist counts as friends or has met in the art world. We crack open our bottles in front of a grid of 15 framework-house studies by the late German artist couple Bernd and Hilla Becher. “I once asked Becher for advice on my photography, and he said, ‘I can’t give you any advice’,” Demand tells me, laughing.

Walking with Demand, I realise, is a free pass to drink water inside a museum.

For his collaborators, part of the package deal that comes with working with Demand is that he will design the exhibition space on top of his curatorial and artistic duties. An architecture buff, the biographic and atmospheric frameworks of Demand’s built spaces have made him a darling amongst those in the profession. By expanding outside his world of models, he’s translated those qualities into how his works and exhibitions are experienced and, chiefly, moved through: with humour, levity, and a touch of melancholy.

The Naala Badu building – where the exhibition is held until January 11, 2026 – was designed by Japanese architecture firm SANAA; Demand also happened to photograph the new AGNSW wing’s maquette as part of a body of work in collaboration with the Pritzker Prize-winning studio.

“When I came here, it was so strangely familiar,” he says, looking up at the ceiling. Demand’s vision was to display his selected works on vast panels, some as wide as 30 square metres, suspended from the ceiling. One of the heaviest works on display is Robert Rauchenberg’s 1989 Yellow visor glut, an object collage of riveted metal parts and a railway stop sign mounted on a black painted panel.

“The museum said, ‘Oh, no, I don’t think we can do that’. And then I said, ‘I think we can do that. I called the architects’.” The result makes these panels seem weightless; painted in a kaleidoscope of colours that gives way to an airy, light-filled space. As we quietly observe other viewers walking behind the levitating walls with only their shoes visible, I point out its perverse humour, like looking beneath an occupied toilet stall.

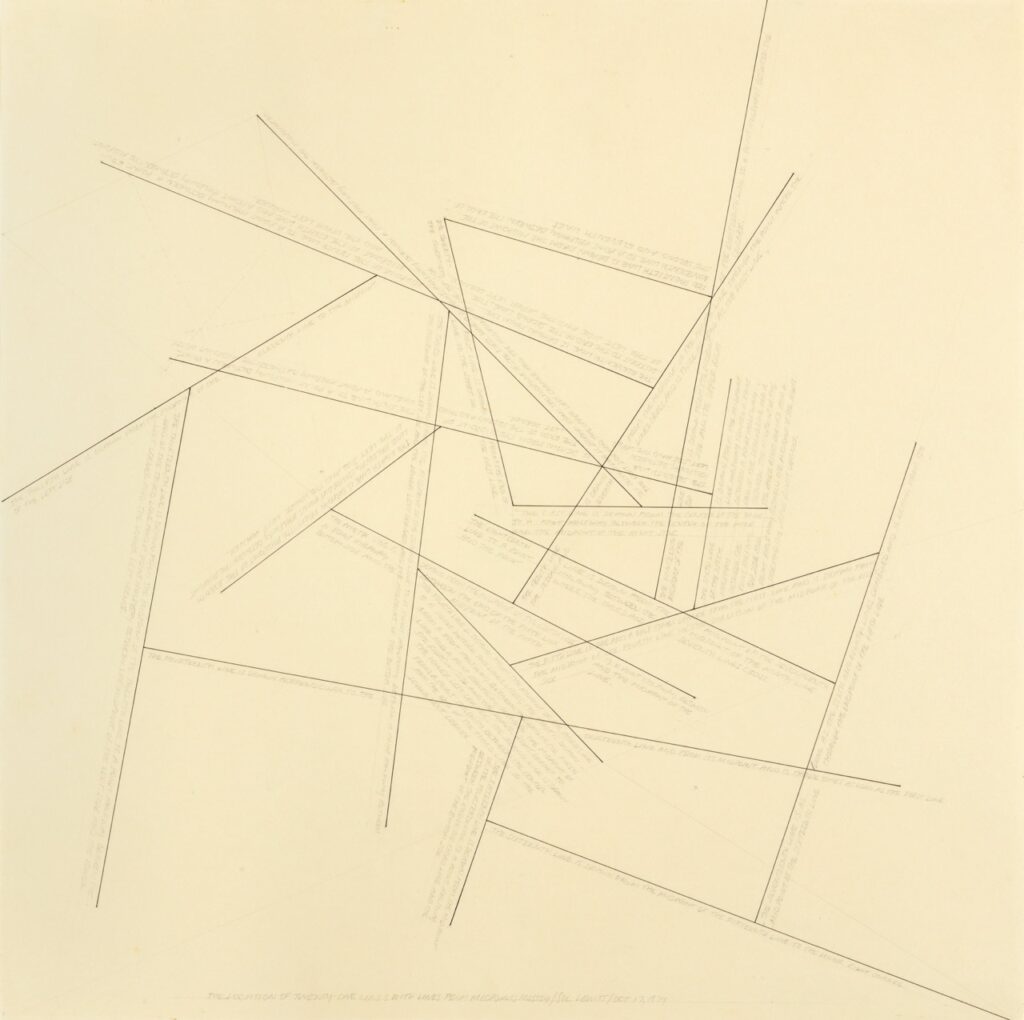

It dawns on me that we’re meandering with no set path in mind; no guiding chronography or organisation in the collection’s predominantly Western canon. This is by design. A drawing by the American painter Sol LeWitt greets you at the entrance, which depicts 21 lines intersecting at different points and lengths. If you were to view the exhibition aerially, its layout is based on the drawing, creating a flow for chance encounters with blockbuster artworks. It represents Demand’s ultimate expression of occupying the space of an artwork.

The room’s wallpaper, printed with dark green beams to give the impression of a dense forest, was also designed by Demand. “It’s like a little village, there’s a trader where you can buy meat,” Demand says, waving his hand at the room’s centre structures, its wave-patterned roof echoing the building’s Welcome Plaza. “I wanted to have a subconscious metaphor underneath the whole thing, a mise-en-scène. I wanted to give it some kind of topography.”

We end at the wall of windows where most of the sculptures are displayed. Mounted on a white wall are six plywood boxes by the American artist Donald Judd. “I know Judd wanted his work on white walls, so I respected that,” he says. “We really worked on this wall to make it the whitest white, to make it pop.”

As the sun climbs towards noon, the Judd wall almost blinding us, I ask him what the best time of day is to visit The Object Lesson. “In the morning, when the light casts these lines on the floor from the window panels,” says Demand. He admires how the dramatic shadows add to the space before looking out at the postcard view of Elizabeth Bay.

Related:

Westwood | Kawakubo: NGV’s world-first exhibition unites two icons who changed fashion forever