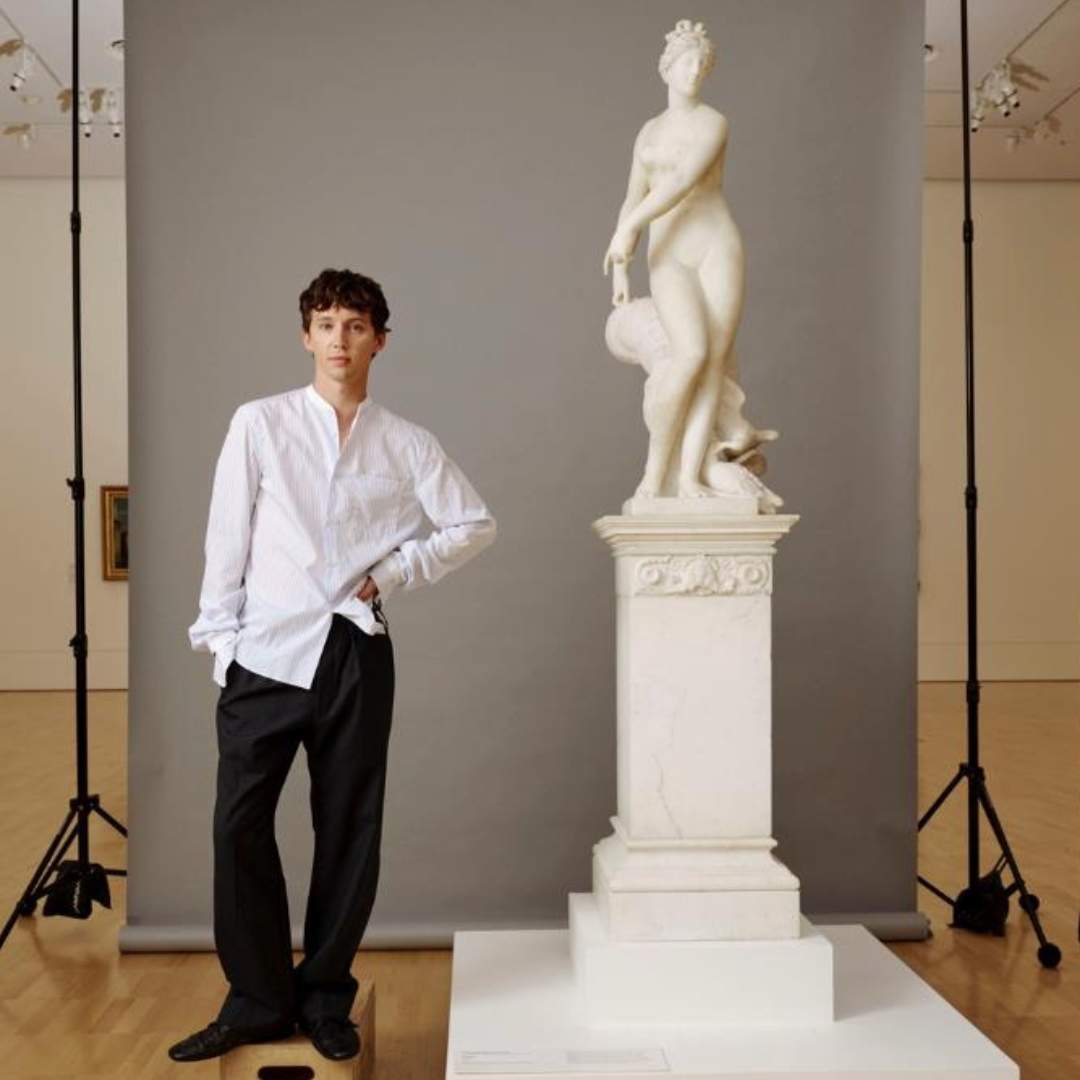

The artist behind the “AUSSIE” poster is about to put up more

Peter Drew’s “AUSSIE” posters are a ubiquitous sight across Australia’s major cities that spark conversation about national identity

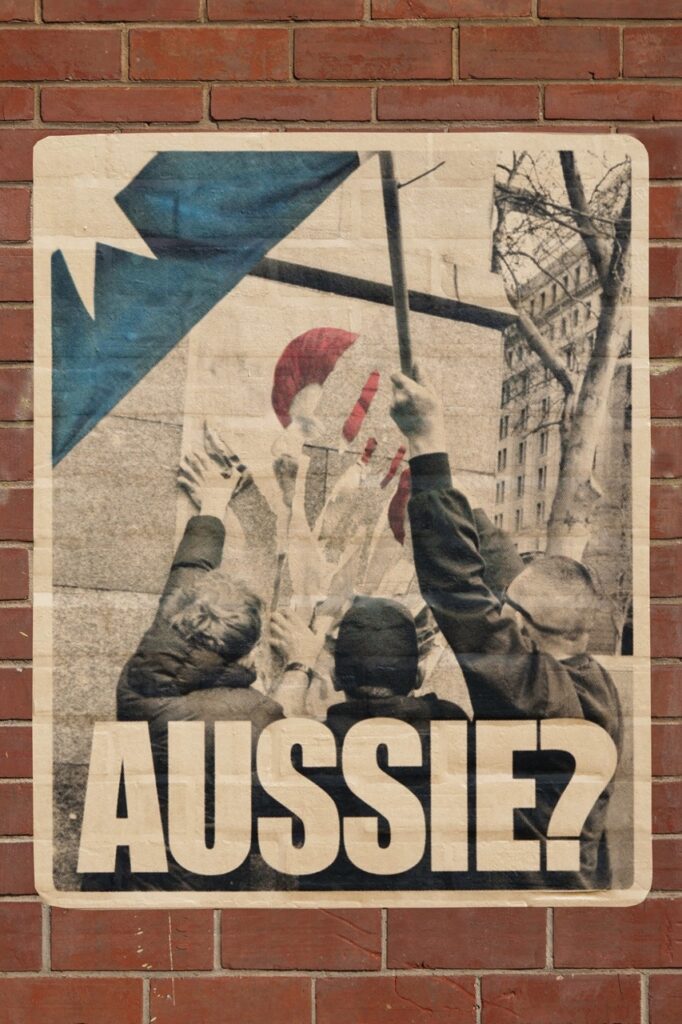

ON THE LAST DAY of winter, three men partaking in the ‘March for Australia’ rally in Adelaide tore down a poster of a brown turbaned man, photographed in regal profile with the word “AUSSIE” typed across the bottom. Other demonstrators, some of whom wore the Australian flag as a cape, cheered and clapped. A few weeks later, Peter Drew, the artist behind the poster, pasted up a new design on that same street corner: a photograph of those three men in the act, this time the word “AUSSIE” punctuated with a question mark.

“It gives me more enthusiasm to put up more posters,” Drew says of the rallies. “I want my posters to affect people: to make people feel like they belong here, [while] others may feel their sense of belonging is being threatened because they have a racially exclusive idea of what it means to be ‘Australian’ . . . That behaviour of theirs, I’d like them to think about whether they are being Aussie.”

Drew, 42, started his Aussie Poster project in 2016 after a wave of anti-Islamic sentiment in Australia in the wake of the Sydney Lindt cafe siege. The posters – lining alleyways, under bridges, on the side of office buildings – use photographs from the National Archives of Australia of people who applied for exemptions to the White Australia Policy. Monga Khan, his most well-known subject and the man in the torn-down poster, was a hawker from present-day Pakistan who moved to Victoria in 1895 to sell local and imported goods.

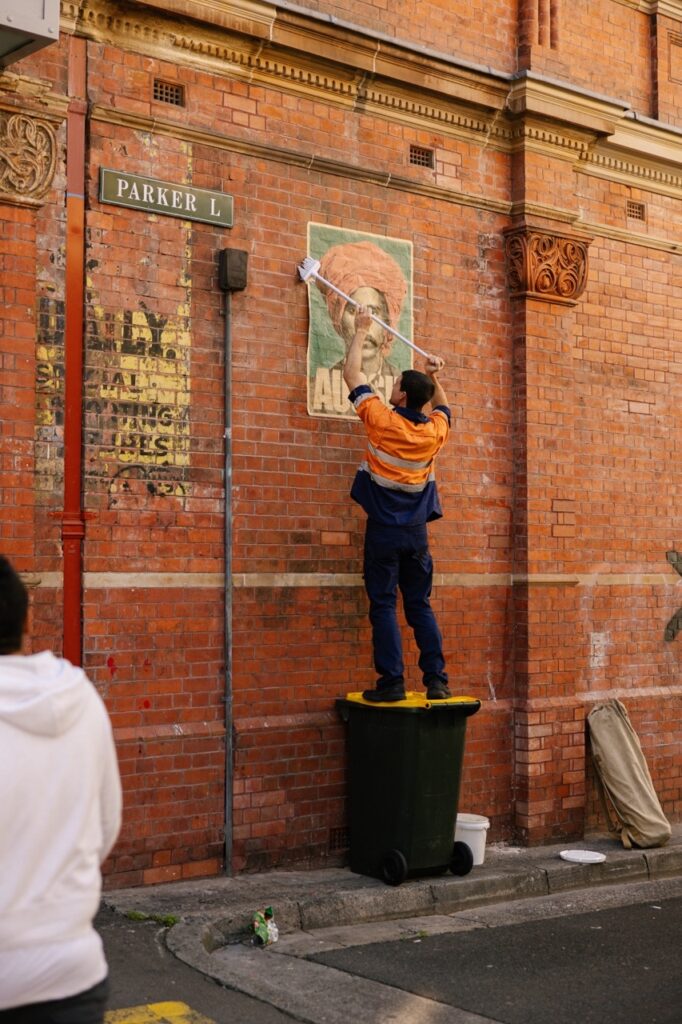

By his estimation, Drew has put up as many as 5000 posters in every major Australian city. And with the rise of anti-immigration marches across the country, where attendees have chanted slogans like “send them back” and “stop the invasion”, Drew has started spending more time at his printer.

He pauses the press one morning to talk to me from his studio in Adelaide, an industrial-looking space with canvases and rolls of brown craft paper stored away behind him. When Drew first started going through archival documents, he was curious about the people frozen in sepia and the kinds of lives they led in Australia. He looks for “what personality is conveyed in the photographs, and it’s often very subtle, the person is not trying to project who they are.”

Another well-known subject is Queensland-born Nellie Chin – bespeckled, hair cut in a bob, and smiling – whose photograph from 1929 was attached to her exemption to the dictation test, so that she could travel back from China without being barred entry on the grounds of her perceived race.

“I think that makes for a very powerful photograph,” Drew says, commenting on her sardonic smile as to what she thought of the White Australia Policy. “Because of the historical facts of the matter, you can’t convey all of that through an image, but you can provoke people’s curiosity, and then the audience will be motivated to pursue more information, and want to identify with the person.”

Where the first project employed empathy, Drew’s new posters respond to the exclusionary far-right patriotism that has stoked fear of so-called “mass migration”. The new posters, he says, aim to “defend our right to be patriotic, and not let the other side claim that space . . . I do think the Aussie Poster project is a positive celebration of Australia, resilience, and people finding a sense of belonging here against the odds. And in that sense, I am patriotic.”

For the majority of next year, Drew will print and glue up 1000 new posters, and print another 500, which he will make available for purchase on his website to fund his journey. He’ll start this summer in Adelaide, then on to the state capital cities and some rural areas. The identities in his new posters will be revealed in due course, though he hints at the inclusion of a Jewish person for the first time and a great-great grandfather of an Australian politician.

The illegality of it is also part of the thrill. He can do it in daylight, too, noting that wearing a hi-vis uniform affords him a level of invisibility. “It’s sort of ironic. No one pays any attention to people wearing hi-vis on the street because you just assume they’re meant to be there and they’re doing their job,” he says. “And that sort of eliminates all the would-be authority that would come up to me and say, ‘Hey, are you meant to be doing this?’”

But it doesn’t stop confrontations with bystanders, who Drew fits into two categories: fearful middle-aged, conservative men (“usually my dad’s age”) who don’t agree with his pluralistic vision of national identity, and people who don’t like the aspirational nature of his posters. “It’s very different to having a conflict online, where someone is right up in your face. It’s pretty visceral,” he says.

This will also be the first Aussie Poster project being documented on his Instagram where he will put out call-outs asking his 44k followers and counting where to apply them. The internet, he observes, is a different place from what it was in 2016 where algorithms habituate conflict in the comment section. “In online discourse, people have got better at being okay with other people disliking you, which is not the way we were taught to approach the internet with optimism and sunshine,” he says.

A week after our call, on October 19, Drew went to the second ‘March for Australia’ protest in Adelaide in disguise. Wearing a black singlet, caped in an Australian flag, and a GoPro strapped to his chest, he set a trap with a Monga Khan “AUSSIE” poster attached to a bucket full of water above. It wasn’t long before an attendee fell for it, leaving the torn poster on the ground as he walked away. “Why did you do that, mate?” a bystander yelled out, “Pick it up.” There is nothing more un-Australian than littering.

Related:

A maverick’s modern art collection, according to Thomas Demand