Forever young: how biohackers seek to prevent the (allegedly) inevitable

Faced with an expanding group of wealthy and eccentric entrepreneurs willing to do whatever it takes to increase their lifespan, the jury's out on whether biohacking is a worthwhile, science-based pursuit or a futile exercise in resisting the inevitable

ON JANUARY 23, 2025, tech entrepreneur Bryan Johnson made an announcement on X:

“Nighttime erection data from my 19-year-old son, @talmagejohnson_, and me. His duration is two minutes longer than mine. Raise children to stand tall, be firm, and be upright.”

It was the kind of tweet that unites the internet in titillated disbelief. Here was a man worth hundreds of millions, someone who spends more than US$2 million a year trying to reverse his biological age, uploading a spreadsheet of his dick’s hardness as though it were quarterly earnings. In that moment, the tech entrepreneur became not just the face of biohacking but its most literal embodiment: the quantified phallus of an industry devoted to eternal performance.

Behind the memes, though, the post crystallised something genuine about the movement. Biohacking, at its heart, is an act of faith in data and self-discipline, based on the premise that age-related human decline is a solvable problem.

“Biohacking isn’t about gadgets or gimmicks,” says American human biologist Gary Brecka, who twice this year brought his “Ultimate Human” tour to Australia. “It’s about taking control of your own biology through measurable, science-backed interventions. Your body runs on chemistry, not opinion. If you change that chemistry, you change how you feel, perform and age.”

Brecka sees himself as a kind of biochemical accountant. “It’s self-biology using data to make informed choices,” he says. “When you fix sleep, oxygenation, methylation and micronutrient balance, you see performance gains that money can’t buy.”

The promise is seductive: replace the vagaries of health with spreadsheets, biomarkers and real-time metrics. For a generation raised on performance reviews and step counters, biohacking offers something familiar.

That corporate precision has its critics. Dr Andrew Lapworth, a cultural geographer at UNSW Canberra, studies how the rhetoric of optimisation migrated from business into biology. “Biohacking denotes a wide variety of practices that engage biomedical and technological innovations to hack bodily processes,” he explains.

Lapworth says that while public figures like Johnson are most commonly associated with the term, “It is important to emphasise that biohacking is a broad umbrella term that points to a diverse range of human-enhancement practices”.

These range from neuro-implants that replace sight, nootropic drugs that boost brainpower, human germline engineering, nutritional supplements, gene doping in sports, cosmetic surgery, growth hormones and anti-ageing medication.

“These are all very different, but what they share is the goal of probing or pushing back the limits of the human body, often outside what is typically considered the medical therapeutic field,” Lapworth says.

But what’s distinctive about this current moment is that the logic of human enhancement has moved from elite contexts – the military, professional sport – into everyday life. It’s a pattern, Lapworth says, that reflects the ambient exhaustion of late capitalism. “The ‘extreme conditions’ of those arenas – stress, competition, endurance – are increasingly normalised in the workplace. Enhancement becomes not about winning, but about coping.”

Lapworth sees in the movement a philosophical through-line from Silicon Valley transhumanism to the quantified-self subculture. “The idea that the body is a machine that can be optimised to yield measurable improvements resonates strongly with the masculinist, entrepreneurial culture of tech,” he says. “It’s a very particular form of selfhood: data-driven, competitive and male.”

Indeed, where wellness has long marketed itself as inclusive – the yoga mat as a communal equaliser – biohacking has been colonised by men in compression shorts, armed with wearables and an obsession with bloodwork. If wellness promises balance, biohacking promises dominance.

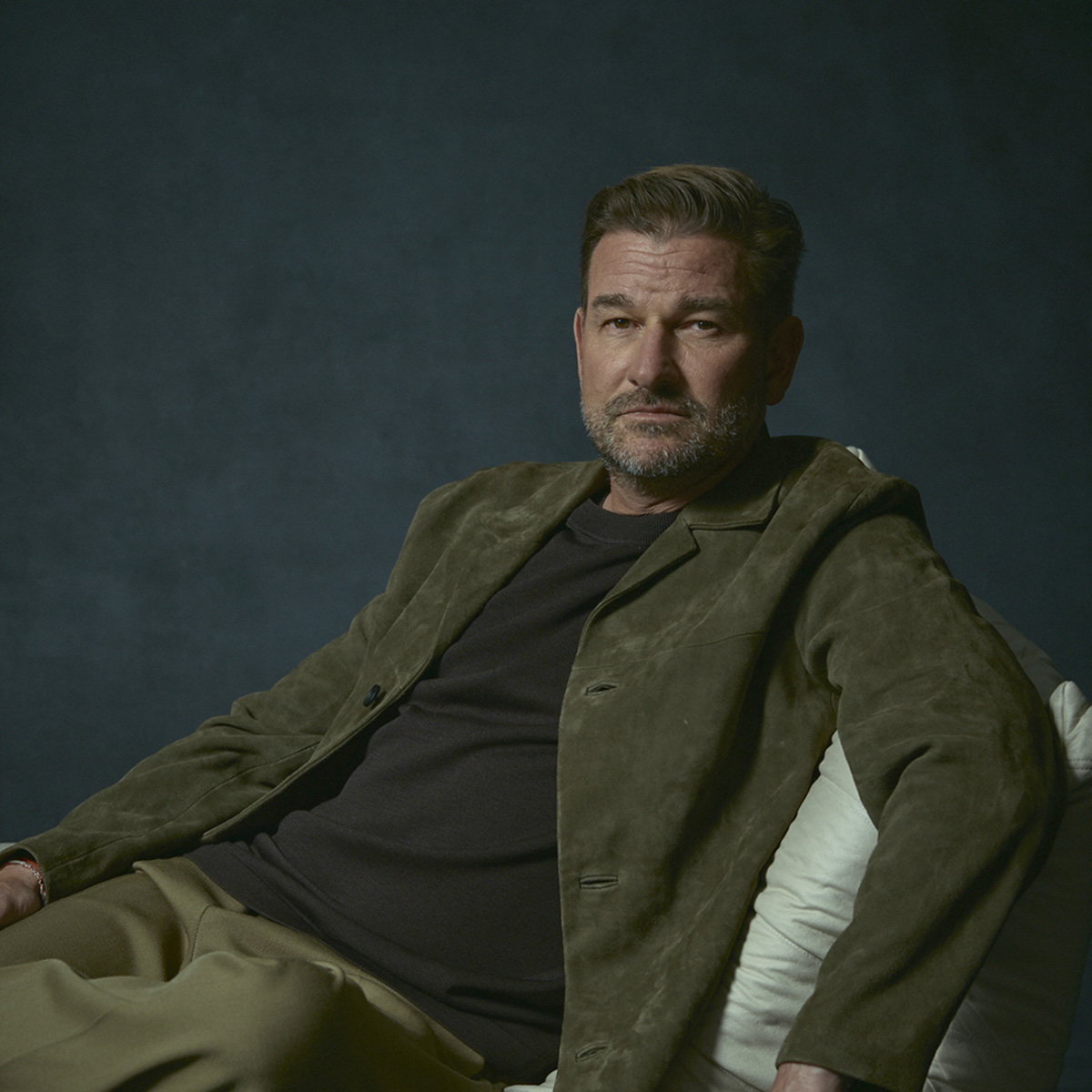

FEW EMBODY THAT aesthetic more suavely than Tim Gurner, whose Saint Haven private clubs repackage the language of longevity as luxury. “Biohacking isn’t about chasing trends,” he insists. “It’s about understanding how our body works and making deliberate choices to help it perform at its best.”

The Saint Haven “stack” – cryotherapy, red light, hyperbaric oxygen, IV drips and lymphatic compression – reads like a menu at the world’s most expensive car wash. Every treatment, Gurner says, is grounded in science: “Our IV infusions are scripted by a GP and supervised by in-house nurses”.

The line between medicine and marketing is, by design, blurred. “We offer a comprehensive approach that combines wellness services with clinical care,” he says. “Our practitioners work together to ensure each member receives care that is both holistic and medically appropriate.”

It’s a delicate balance – the spa as lab, the gym as clinic – and one that speaks to a broader cultural drift. Health has become lifestyle, and lifestyle has become something to monetise.

And there’s definitely money to be made. After the success of his first space, Gurner has his eyes set on Sydney with a massive six-storey, 3000-square-metre space in North Sydney – double the size of his current club footprint.

Tristan Sternson’s entry into biohacking came after years of operating “at maximum voltage,” as he describes it. A lifelong technologist and serial entrepreneur, he spent more than two decades building and scaling companies before his body began to revolt. “I’d sold a company, burnt out, ended up in hospital,” he says. “I realised if I was going to do it again, I had to do it smarter.”

That crash became the data point that changed everything. He began testing his blood, hormones, DNA and gut microbiome. “I look at 65 biomarkers every four months,” he says. “Initially, I just wanted to find out what I was deficient in. Vitamin D, hormones, energy production. Then it became about optimisation and longevity.”

His mornings now start before sunrise: a four-minute plunge into a three-degree ice bath, followed by breathwork, gym training and a meditation he treats as seriously as high-stakes business. “It’s probably the toughest thing you’ll do any day,” he says. “I do it in front of my kids, so they see it. You don’t have to do it every day physiologically, but for mental resilience, I do.”

Sternson admits the optics of the biohacking routine can look extreme to those on the outside. “It could be a full-time job,” he says, “but I fit it into my routine. Sleep, diet, exercise – those are free. The other stuff just adds a layer of data.”

Yet compared with the movement’s most devout adherents, he’s slightly more pragmatic in his view of its end goal. Longevity, argues Sternson, is about quality of life, more so than quantity. “If I live to 80, I want 80 good years,” he says. “I’d take that over 120 average ones.”

The academic view leans towards scepticism. Lapworth describes biohackers as “connoisseurs of science, somewhere between expert and amateur”. They can challenge orthodoxy, he says, but they also risk confusing experimentation with expertise. “A diverse base of amateur practitioners can sometimes uncover new innovations,” he notes, “but enthusiasm often outpaces evidence.” That distinction matters, particularly when the aesthetics of scientific legitimacy – lab coats, data visualisations and the word ‘protocol’ – become part of the sales pitch.

“Biohacking done right is measurable,” Brecka insists. “This isn’t mysticism, it’s biochemistry.” But he’s also aware of the movement’s weakest link: “The biggest risk is losing scientific integrity to trends”.

The medical establishment, for its part, regards most longevity claims as sitting somewhere between plausible and premature. Still, as Lapworth points out, the creative and subversive use of biotechnology isn’t simply a fad, and a diverse base of amateur practitioners can sometimes uncover worthwhile innovations. Biohackers, he says, can act as “science connoisseurs” – a bridge between experts and the public.

IF BIOHACKING HAS a pope, it’s probably Johnson, purely because his antics have tapped into our meme culture. He is part prophet, part performance artist. In Interview Magazine earlier this year, he declared, “People have been chasing the fountain of youth since time began, but this is the first time in human history where you can legitimately imagine arresting ageing”.

He claims to have slowed his “speed of ageing” to 0.57, meaning his biological birthday arrives every 21 months, and boasts “the best biomarkers across 44 categories of anybody in the world”. His body, he says, is “an Olympic gold medal in health”.

And then there are the erections. In the same interview, Johnson explained, without irony, that “boners are one of the most important indicators of your health,” adding, “If a man is not having boners, he’s 70 per cent more likely to die prematurely”.

It would be easy to dismiss him as a walking satire of self-quantification, Patrick Bateman in a Fitbit, but his extremity reveals something truer: biohacking’s underlying moralism. Johnson’s mantra, “Never trust humans, always trust data”, is less about immortality than about purity. Sin, recast in biochemical terms, becomes sugar, alcohol and lack of sleep. Salvation lies in spreadsheets.

The irony, of course, is that for a movement obsessed with health, the lifestyle often looks joyless. “It could be a full-time job,” Sternson says. “You just have to fit it in.” Even Gurner, whose Saint Haven clubs resemble luxury monasteries, frames longevity as an investment strategy. “Longevity is often seen as a luxury,” he says, “but when approached correctly, it’s an investment in health span, extending the number of years you can live well.”

Lapworth is more circumspect. “The fear is that biohacking could become less a choice and more a compulsion to keep up,” he says. “We can see, for example, the increasing non-medical use of psychostimulants to improve physical and intellectual performance in light of difficult work conditions.”

In that sense, biohacking might be less a rebellion against ageing than a continuation of capitalism by other means. The body, once again, must perform.

Still, it’s hard to dismiss the sincerity of its believers. Brecka talks about “compressing morbidity” – living fully until the very end. Sternson jokes that his children now refuse birthday cake because of the sugar. Even Johnson, the movement’s most polarising evangelist, seems earnest beneath the spectacle. “When I grow younger,” he told Interview magazine, “is my mantra.”

Perhaps that’s the final contradiction of biohacking: it’s both a parody of self-improvement culture and a perfectly rational response to it. The desire to feel better, live longer and make sense of the chaos is as old as medicine itself. Only the interface has changed.

And so, as the algorithms hum and the data streams flow, Bryan Johnson’s penis remains, improbably, uncomfortably, the most famous symbol of human optimisation. The body, quantified at last, has finally achieved what Silicon Valley always promised: virality.

Related: