How a toymaker found his voice in art

Opening his first solo Australian exhibition at the Museum of Old and New Art, Arcangelo Sassolino speaks to Esquire about the making behind his “psychological traps” with industrial materials

IN THE AUTUMN OF 1992, Arcangelo Sassolino was on a date at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. His date, the daughter of a prominent New York art collector, had two tickets to see the Henri Matisse retrospective, a mammoth 400 works laid out in broad chronography. But it was in the final room before the gift shop where Sassolino found himself enamoured with Matisse’s drawings with scissors.

The French painter’s cut-out period was his second life in art, and, arguably, his most well-known. After being diagnosed with intestinal cancer, he was left bound to a bed and wheelchair for the remainder of his life. During this period, Matisse missed sitting by the pool so he informed his studio assistant that he “wanted to see divers”. For what would become Swimming Pool (1952), they made cut-outs of divers from azure blue paper and collaged them against a white band of paper that lined the walls of his dining room in the Hôtel Régina.

“[It’s] that joy of making with your hands and making something that is unique and wonderful, and so simple with so much grace, beauty, and thought,” says Sassolino. “Those rooms really saved my life, in a way.” Call it being young in New York City, either way, Matisse’s message was clear: It’s never too late to seize your second life.

At the time of the revelation, plenty was happening for Sassolino, who was working as a toymaker for Casio Creative Projects. His ticket to the United States came in 1990 after patenting a three-dimensional puzzle he created while studying mechanical engineering in his native Italy. He didn’t attend a single class; he never finished the degree. Sending the patent to a Manhattan toy manufacturer, they referred him to a three-month internship at Casio, which turned into six years of inventing and developing games and toys.

Soon after visiting the Matisse exhibition, however, Sassolino had enrolled himself in the sculpture program at the School of Visual Arts (SVA). By 1996, one toy was picked up by Mattel, the creator of Barbie, and so Casio offered him a contract to stay on for three more years. Finishing up his studies at SVA, Sassolino had already made up his mind. “At that point, I knew it was time for me to move on and fully dedicate myself to art. After all these years, the company [and I are] still very good friends,” he tells me, smiling. “They knew that I had to take that step, that I had to move on.”

He returned to Italy, armed with the conceptual frameworks he learned at SVA, where he spent his early years as a young artist travelling through Pietrasanta and Carrara, learning the Alpine region’s marble carving tradition. Like any self-taught artist by this point, it was a time of “great experimentation, even though rather naive at times,” he once described. By the new millennium, he settled his studio in Vicenza, his hometown and from where he’s speaking to me one early morning.

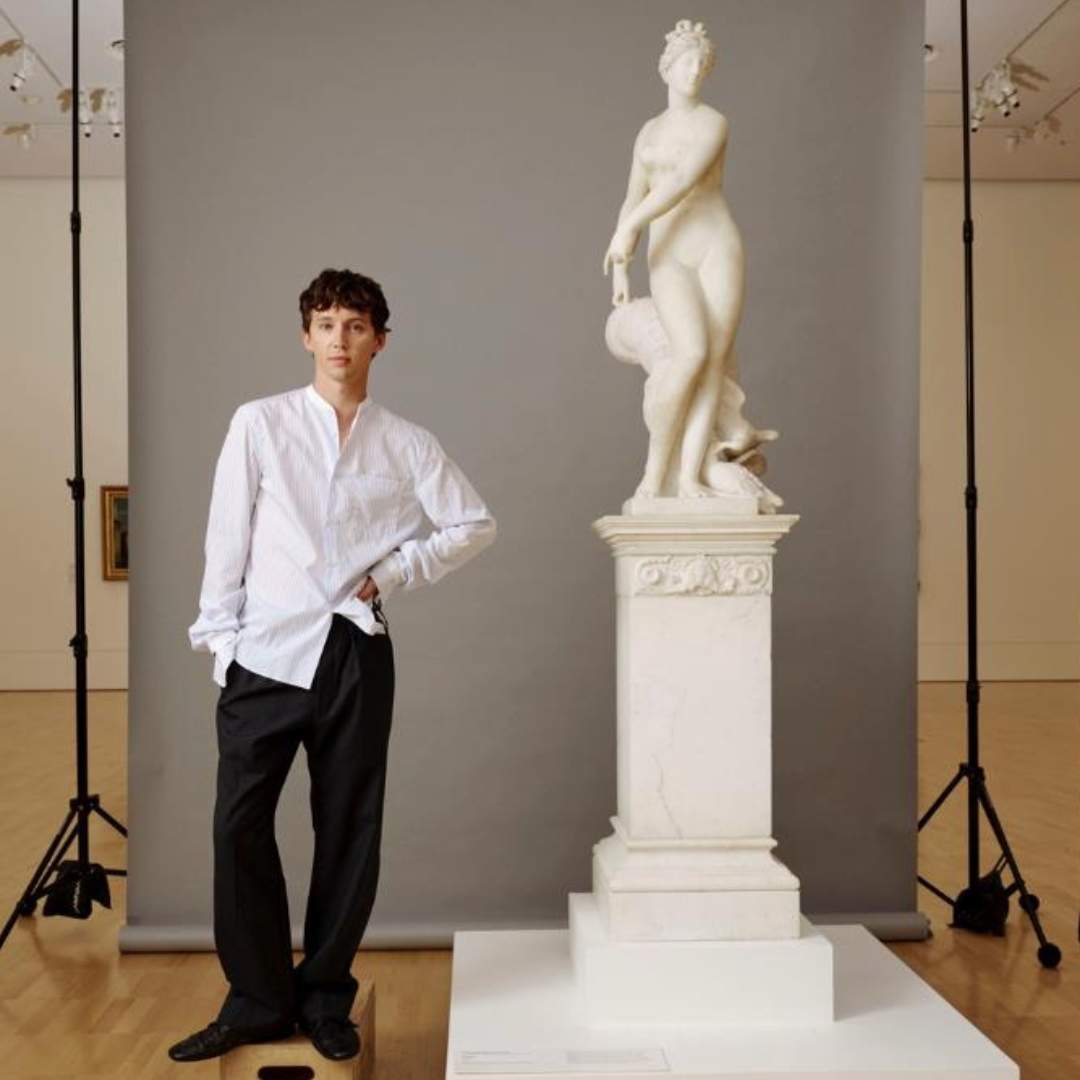

Sassolino, now 58, has just returned home from opening his first solo Australian exhibition in Tasmania’s Museum of Old and New Art. The exhibition, titled in the end, the beginning, brings together five major works he describes as “psychological traps”. In violenza casuale (2008 – 2025), there’s the pungent smell of one room filled with rectangular slices of industrial wood, each fated to be tied to a hydraulic cylinder until it splinters in half, its remains discarded thereafter. Continuing on material carnage, the paradoxical nature of life (2025) consists of a granite boulder placed on top of a thick piece of glass held up by steel. The glass bows, but it won’t snap – for now. Sassolino has tested it again and again to be held in suspended anticipation.

These industrial materials would have otherwise remained static, stored away in a warehouse waiting to be activated once manufactured as part of a tool. What Sassolino does is imbue them with a ticking clock. How he goes about deciding what materials to use in these ephemeral sculptures, he paraphrases the Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncuși: “You must know the material before touching it”. “I feel like different materials talk to me,” he continues. “I understand the characteristic it comes with – that aspect comes very easily to me. I try to understand what a material can be, or apply it to my own way of thinking . . . I’m much more interested in squeezing out the soul, the voice out of the material. Sometimes even the perfume, just something unexpected that is embedded.”

The Vicenza of his youth was more provincial farmland than the industrial hub it is today. His father, a craftsman who passed away when he was a boy, left a sense of thinking through three dimensions as Sassolino tinkered away most afternoons after school in his family garage cutting, gluing and building aeroplanes. The city’s Palladian architecture, too, with its emphasis on proportion and symmetry, has been a lasting influence in Sassolino’s life as an artist. “I feel those rules,” he says, “That’s the reason why I came back because if you make peace with your roots, you can grow something from there, you know?”

Since moving back to Vicenza, Sassolino has surrounded himself with a network of electronic manufacturers to source his materials from. One of them is CEIA, the Arezzo-based manufacturer of metal detectors. “I’ve learned how to approach companies because sometimes people are a little bit suspicious of the artist,” he says, laughing, “but now I know how to talk to the engineer, the artisan.”

The exhibition’s title work uses the company’s electromagnetic induction technology to rapidly melt down steel at 1500 degrees. Sassolino first used it in his installation, Diplomazija Astuta, at the 2022 Venice Biennale. The molten rain lit up a darkened room in the Malta Pavilion, evoking the dramatic and voluminous contrasts of light and shade – or chiaroscuro – of Caravaggio’s 1608 altarpiece painting, The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist. Where Diplomazija Astuta would send these droplets into vats of water to sizzle back into solid form, in the end, the beginning drips the molten steel on the ground in the subterranean space, shattering into splashes of light and heat.

Video credit: Jesse Hunniford; courtesy of Mona

One CEIA engineer, who Sassolino has since befriended, couldn’t believe the artistic application that turned his livelihood into something worthy to be put in a museum. “They were amazed at how they didn’t see that possibility until I asked for that possibility,” says Sassolino, getting giddy. “If you think about it, this is exactly what an artist does, you know? [We] produce new images, forms, installations.”

During the Islamic Arts Biennale in May, Sassolino presented an earlier version of no memory without loss (2025) in Jeddah, which involved a massive wheel smattered with thick black oil propped up on the wall, rotating slow enough for the viscous liquid to be scooped up by gravity before it could drip on the floor. As an Iranian man stood before the slick abyss, he told Sassolino how he recognised political instability in the work. A moment later, a cardinal chimed in, saying he understood the work through his faith. Sassolino leaned back and let the active discussion unfold.

“I enjoy hearing people apply their metaphor to a piece,” he tells me. Despite the political readings, Sassolino strictly maintains that he doesn’t set out with an agenda. (When I asked him how contemporary life is making him feel, and art’s role in it, he shared: “It’s about bringing people together. It’s about tolerance. It’s about respect. It’s about raising the big questions of who we are as human beings. And it’s not about dropping bombs.”) Considering these visceral reactions further, with how, for instance, audiences experience the molten explosions in the end, the beginning behind safety glass, “There are people who are scared, and there are people who are very attracted by it,” he observes.

How Sassolino sees it himself, working with industrial materials in dangerous proximity, put simply, “is a consequence of what I do.” “My work is not only something that you elaborate with in your mind, but it’s also something that somehow engages you physically,” he continues. “This little danger, the contemplation of disaster, is something I need in my work.” Throughout our conversation, Sassolino speaks about his delight in spectator interpretation in equal parts childlike wonder and brilliant inventor. Either way, the toymaker’s enchantment remains. He adds, smiling: “Art never has to give answers. Just raise questions.”

Arcangelo Sassolino’s in the end, the beginning exhibition is on view at Mona until April 6, 2026. Learn more here.

Related:

Westwood | Kawakubo: NGV’s world-first exhibition unites two icons who changed fashion forever