Author David Nicholls on 'One Day's' second shot

EVEN NOW, people want to talk about One Day. It’s something I’ve lived with for 15 years.”

David Nicholls is recalling the book that changed everything. His 2009 novel One Day is the story of two friends who should be together. Held back by circumstance and self-sabotage, they almost miss their chance. The will-they-won’t-they couple is a stock premise, but Nicholls subverts it with a clever structural conceit. We meet Emma and Dexter on the same day (15 July, the anniversary of their first meeting), every year, for 20 years.

One Day was a global bestseller, shifting five million copies in 40 languages. It was the kind of book people proselytised about and pressed upon their friends. A stranger pressed it on me: the first and only time this has ever happened. I was on a plane and the woman in the next seat had been reading it all the way from Doha. As we stood up to collect our bags, she handed it over. “Don’t you want to keep it?” I asked. “No,” she said. “I want to pass it on.”

A hit like this plots the course of an author’s career. It also comes with a caveat. You have to be prepared to talk about it for the rest of your life. Nicholls has published two books since then, and written several screenplays, including his acclaimed adaptation of the Patrick Melrose novels. He is still being asked about One Day. This month, Netflix will release a fourteen-part series based on the book. So the questions look set to continue.

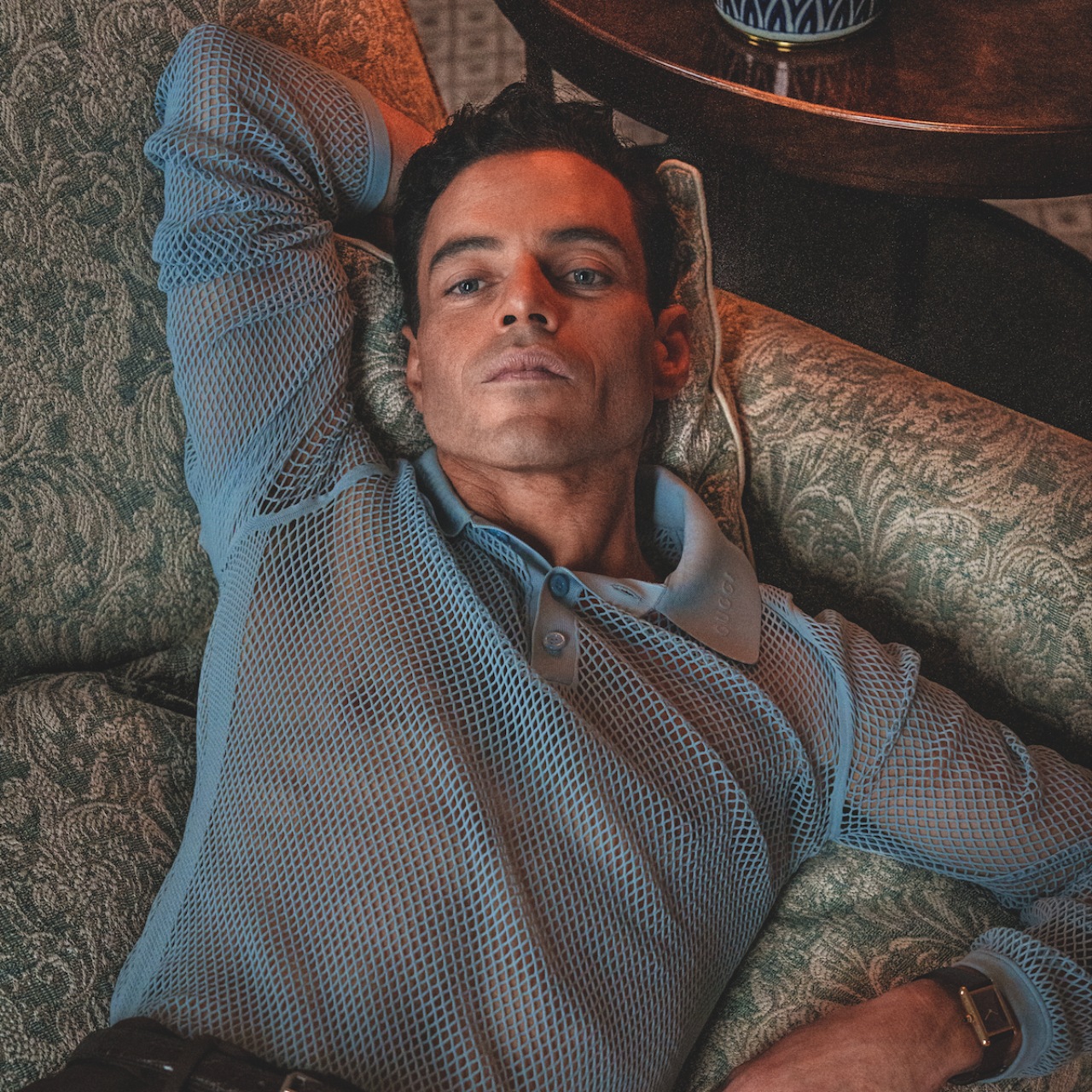

The new show stars Ambika Mod and Leo Woodall. While not exactly unknowns (Woodall was last seen in season two of The White Lotus, as rough-trade-turned-cats-paw Jack; Mod played junior doctor Shruti in This Is Going To Hurt), they’re far less famous than the actors who last took on the parts. This is not One Day’s first adaptation. There was a 2011 film, starring Anne Hathaway and Jim Sturgess. I ask Nicholls what will be different this time around:

“The form is the big difference. This structure didn’t exist when the book came out. In the film, the chapters, the days, become story beats that are part of a larger arc: links in the chain. In a series, each chapter, each day is a story in itself, with a beginning, middle and an end. (It often has) its own style and tone; a solo piece, a romantic comedy, a darker drama, a farce. Which is a terrific freedom for the screenwriters.”

One Day (the series) is part of a wider trend. Like Harry Potter, Mr and Mrs Smith, Fargo and Reacher, it’s a long-form reboot of a relatively recent film. It’s hard to shake the feeling it’s also a bit of a do-over. One Day was a big, ambitious book; broad in scope and packed with small period details that administered a series of Proustian shocks: Oh I forgot about Kula Shaker! And Echobelly! And Shed Seven! And Patrick Cox! And the New Lad!But the novel’s neat format seemed to blur on the screen, the years melding interchangeably. And even with round glasses and a patchy dye job, Hathaway couldn’t convince as the chronically insecure Emma. This is the problem with grafting huge Hollywood stars onto quiet English stories. The nuances get bleached in the glare of their wattage. They can’t pass as normal people.

Streaming hasn’t just changed the shape of our shows. It’s altered the way we see actors. As the screens they appear on keep shrinking, so film stars’ clout has declined. When their faces were blown up on projectors, they seemed almost superhuman. Now they’re figures we press pause on, or half-watch while we scroll. Do you know who was nominated for Best Actor at the Oscars this year? Do you care? But what’s bad news for the A-List is good news for producers, since they no longer need a marquee name to get their project made. In fact, new actors can be preferable, because they don’t drag in the baggage of their previous roles.

“We loved the idea of finding fresh faces and letting the audience discover Emma and Dexter, discover the performers along with the characters,” Nicholls explains. “Ambika and Leo were so good individually, and really wonderful together. It was a very straightforward decision.”

Of the two, Woodall probably has the harder job. Emma is flawed but sympathetic. Dexter is a tougher sell. His type, the blithe public schoolboy who keeps on failing upwards, will be instantly recognisable to anyone who has ever worked in the media, lived in London or been to university. Woodall invests the role with a shambling soulfulness, so he’s never quite awful as he should be. And it’s important that Dexter stays this side of nice. If they made him horrible, they’d risk alienating the book’s massive male fan base. This is what made it truly unusual, when it first came out. It was a romantic novel read by men. I can still remember seeing Facebook posts from male friends who hadn’t touched fiction in years, raving about One Day. The Times called it ‘a book for women that made men cry’. Feared literary critic Rachel Cooke told her husband to read it, then caught him ‘quietly blubbing in bed.’

Dexter seems more vulnerable,” agrees Nicholls. “The good intentions behind the bad behaviour are clearer now and I think it’s to do with the quality that Leo has brought to the screen. People often talk about adaptation in terms of script, but almost as significant, if not more, is the casting. When you have wonderful actors, they bring out…different elements.”

Nicholls is executive producer, so it’s part of his remit to rave about his leads. But on Mod and Woodall, he isn’t wrong. They are both very good. If One Day asks why certain people get under your skin and cannot be dislodged, their chemistry supplies a plausible answer.

One Day is on Netflix from 8 February.

This story originally appeared on Esquire UK.

Related: