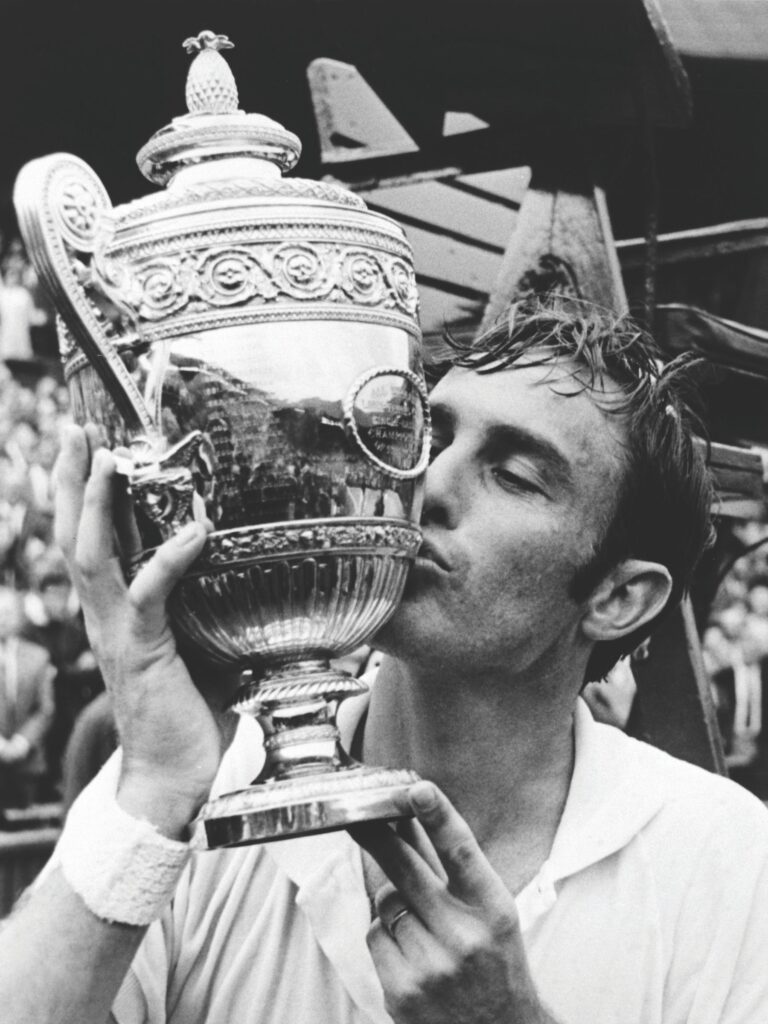

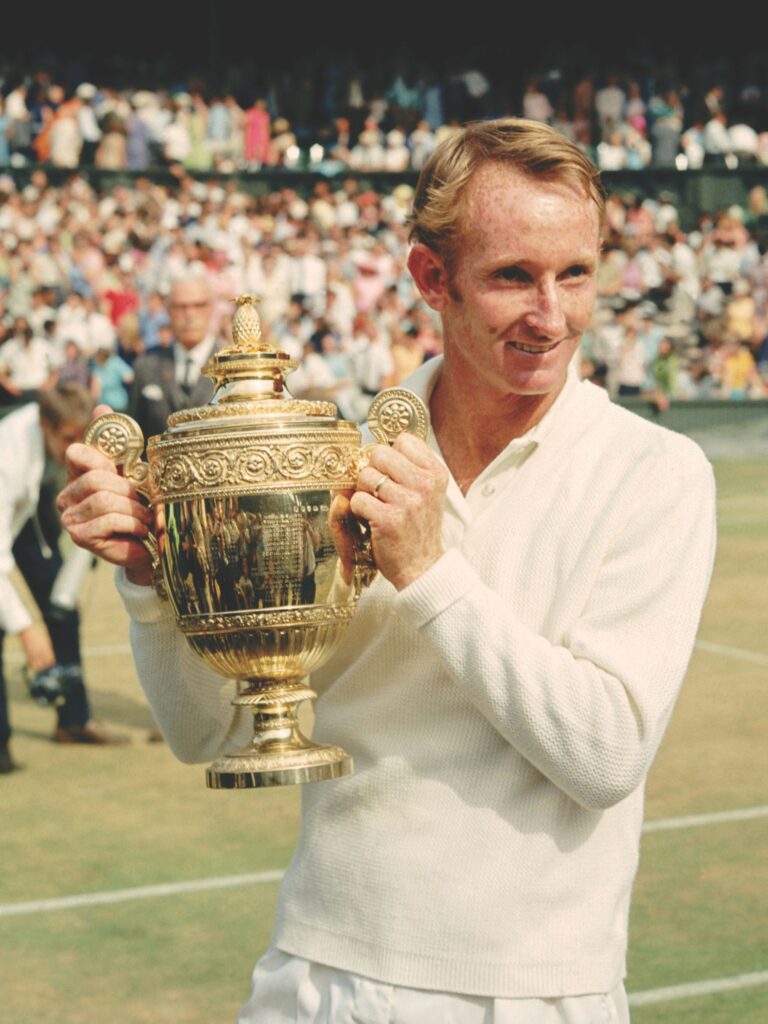

IT MIGHT SEEM HARD to believe, but there was a time when winning Grand Slam tennis titles was, for Australians, like shelling peas. Easy pickings. Through the ’50s and ’60s, Australian men dominated the world, winning a whopping 58 major singles titles out of a possible 80, as well as the Davis Cup – tennis’ most prestigious team competition – 15 times out of 20. Rod Laver, Ken Rosewall, Frank Sedgman, Lew Hoad, Ashley Cooper, Roy Emerson, Neale Fraser, Tony Roche, John Newcombe and others became household names, as did Margaret Court on the women’s side (and later, Evonne Goolagong Cawley). Back then, three of the four majors were played on grass, the domain of Australians, whose serve-and-volley expertise perfectly suited the slick, lowbouncing surface. Glory days.

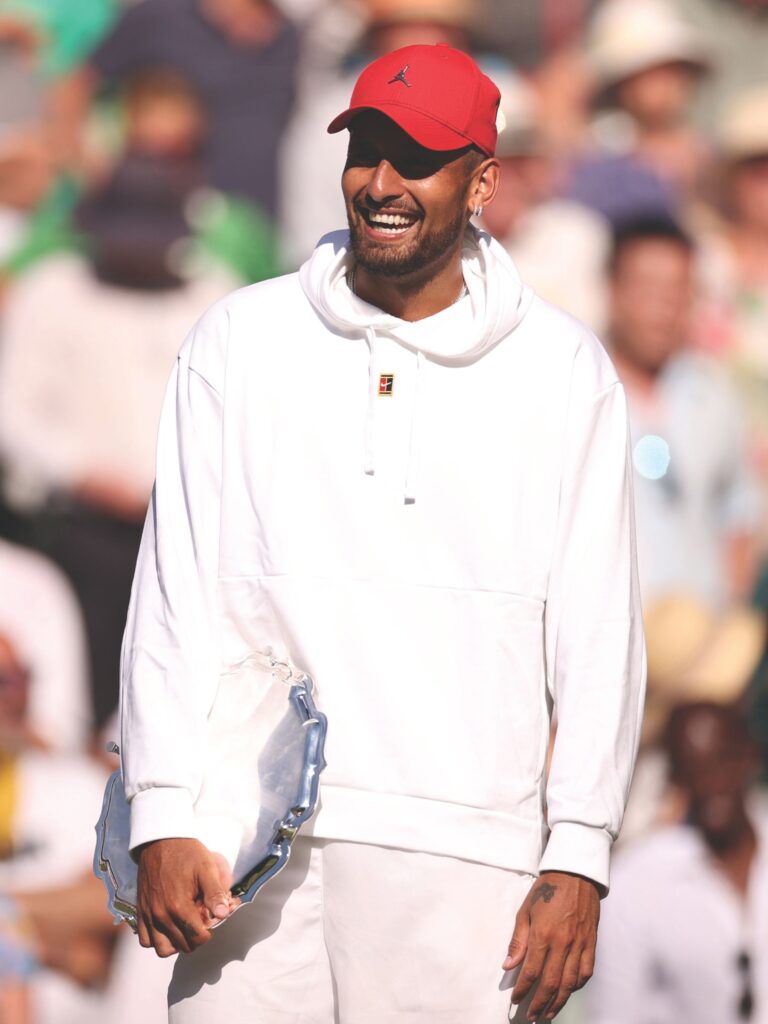

Today, Wimbledon is the only Grand Slam event still played on grass, and as other nations have caught up and then surged ahead, Australians have found it much harder to compete. There have still been champions: Pat Cash, Pat Rafter and Lleyton Hewitt all tasted Grand-Slam glory, as did Sam Stosur and Ash Barty. But Hewitt, at Wimbledon in 2002, is the last Australian man to win a slam, while Nick Kyrgios, at Wimbledon in 2022, was the first Aussie man to make a major singles final since Hewitt was runner-up to Marat Safin in Melbourne in 2005.

To be fair, over the past two decades, winning a men’s singles title at a Grand Slam has been one of the most formidable assignments in sport. The dominance of Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic left very little room for anyone else to get a look-in. From Wimbledon in 2003 through to the US Open in 2023, the Big Three won 66 slam titles out of a possible 81. It was, in terms of playing standards and rivalries, a golden period for the men’s game.

For everyone else, though, the Big Three’s supremacy reduced the opportunities for others to come through. Andy Murray and Stan Wawrinka somehow managed to win three apiece, but in that period, Carlos Alcaraz was the only other player to win more than one.

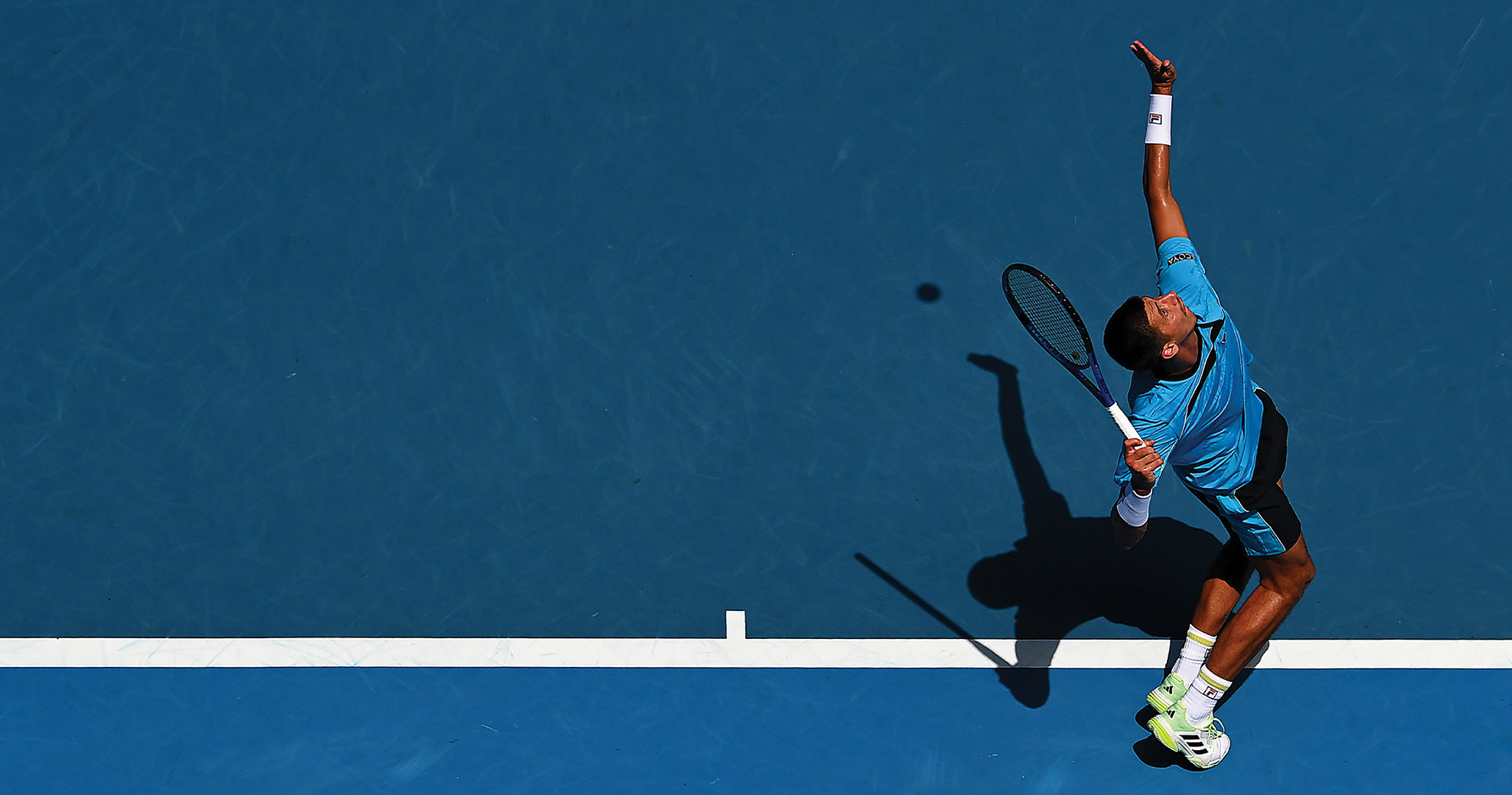

With the retirements of Federer and Nadal, and with Djokovic turning 38 on May 22, a window has finally opened. And though Jannik Sinner has jumped straight through it, winning two majors in 2024 and finishing the year as world No. 1, the chance is there for others to step up. That includes Alex de Minaur, who is leading a new generation of Aussies intent on forcing their way into contention for the biggest prizes.

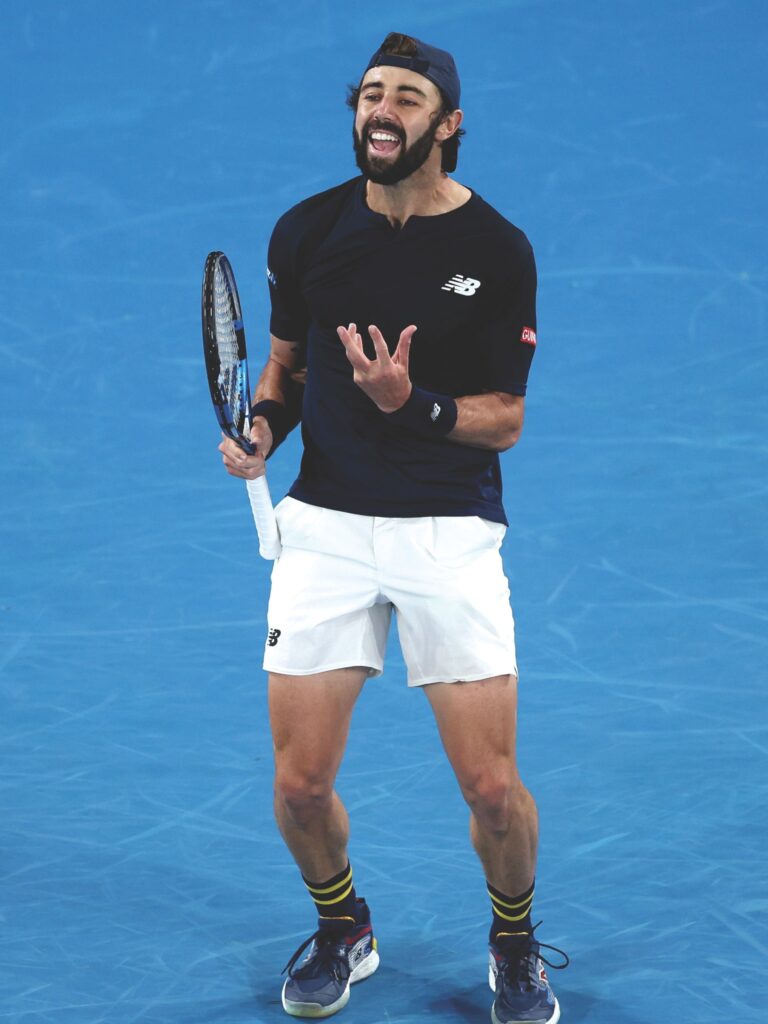

Nine Australian men finished last year ranked in the world’s top 100 – the most since 1981, and second only to France, who had 12. In de Minaur, who in November qualified for the season-ending ATP Finals for the first time, we have someone who leads by example. His influence, along with that of Davis Cup captain Hewitt, has inspired a group of Australians to push themselves higher in the rankings than many expected. Alexei Popyrin and Jordan Thompson have cracked the top 30 for the first time, while Chris O’Connell, Aleksandar Vukic, Rinky Hijikata, James Duckworth, Thanasi Kokkinakis and Adam Walton have all established themselves in the top 100. At one stage last year, there were 10 Aussies in there, with Max Purcell dropping out only in the closing weeks of the season.

How have they done it? To de Minaur’s mind, it’s been about hard work and strength in numbers. Having numerous compatriots on tour and seeing one another push themselves every week, he feels, should produce one or two players who climb to the very top. It’s an ongoing process but one that de Minaur views with ride. “It is great that, in Aussie tennis, we’re just showing what we can do,” he said at the US Open, where he reached the quarterfinals of a slam for the third straight time, beating Thompson in the fourth round. “We’re putting ourselves in the deep end of tournaments.”

Todd Woodbridge shot to fame as one half of one of the greatest doubles pairings of all time. He and Mark Woodforde – ‘the Woodies’ – won 11 Grand Slam titles, Olympic gold in 1996 and the Davis Cup in 1999. Now a television broadcaster, Woodbridge has worked as head of men’s tennis in Australia and backs de Minaur’s take.

“I’m a big believer in having numbers that allow your players to look at each other and go, ‘Well, if you can do that, I know I can’,” Woodbridge says. “I spent three years as head of men’s tennis and you try to use what you think works, what you’ve seen work. And that was part of what I tried to build – to create opportunity for our players to be able to get out on the tour, build our numbers and then watch each other and use each other to make each other better. I think our group of players are doing that well. And that’s a very Australian trait.”

From de Minaur down, the common attribute among this generation of Australians is that they all work hard, they’re all exceptional athletes and they all fight to the end, an attitude embodied by Hewitt as a player and Davis Cup captain.

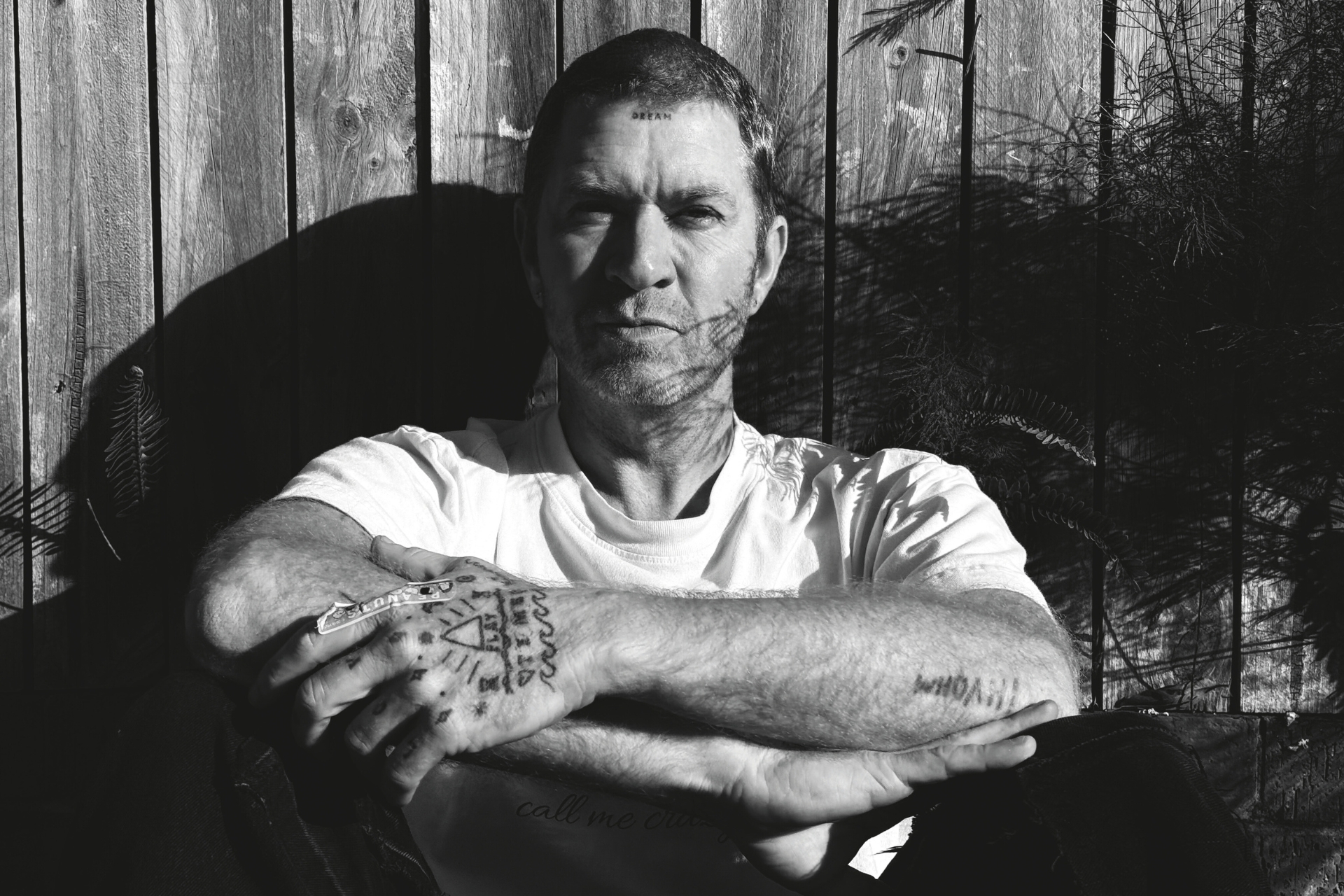

“Lleyton’s great at the Davis Cup and brings some of the guys in,” says Pat Cash, the 1987 Wimbledon champion. “He reinforces that tradition that we’ve always had from the days of Harry Hopman [the former Grand Slam finalist who became a legendary coach and Davis Cup captain] all the way through. It’s hard work. You go out there and you don’t even blink at playing for four or five hours.

“We’ve always had a tradition of hard workers in Australia. I mean, really hard workers. And you’ve got to work ridiculously hard. The ones that haven’t worked as hard, somebody like [Nick] Kyrgios, super talented . . . he gets away with a lot of stuff because he’s just got a lot of talent. But by and large, the guys work really hard. They put the effort in. It’s good to see those guys come through. Guys like [Jordan] Thompson . . . just an amazing effort. He’s a very good doubles player, a Grand-Slam champion now. Sometimes it just takes a few years on the grind, to get out there and work out their game. The men’s tour is tough; it’s brutal.”

From de Minaur down, the common ATTRIBUTE among this generation of Australians is that they all WORK HARD

Each year, the Australian Open hosts a special ‘Legends Lunch’ on finals weekend, a star-studded celebration of Australian tennis. Attended by seemingly all the country’s living greats from decades past, the lunch honours one player each year for their contribution to Australian tennis. The players share stories from their glorious pasts, serving as examples and inspiration for any younger players in attendance.

When Cash and Woodbridge were growing up, many of those legends from the ’50s and ’60s were still quite close to the game and always there for advice. Having the likes of Laver in their ear is something players from other countries could only dream of. “It was an absolute inspiration,” Cash says. “I got to hit with Neale Fraser, with Rod Laver and Ken Rosewall, and got to chat with them from time to time. It was such a thrill for us.”

Woodbridge agrees. “When I was growing up, I had the likes of John Newcombe, Tony Roche, Fred Stolle pull you aside and chew your ear off a bit,” he says. “Sometimes they said to get yourself into gear. They didn’t hold back. But they were also positive. I think that’s what is happening now, too. In this case, you’ve got the likes of, let’s say, Matt Ebden, in a second part of his career, doing well in doubles. You’ve got Jordan Thompson, as well, driven in a sense by a Lleyton Hewitt, who’s been at that coalface since [his] playing [days].”

The presence of so many legends is an inspiration but could also be seen as adding pressure and expectation onto young players trying to come through. “One of the very first articles written about me at the age of, I think, seven or eight, in my local paper was [to the effect that] my partner and I were the next Hoad and Rosewall,” Woodbridge says. “It’s always something that is there in Australia, but as you get better, and as you get on the tour, you start to learn how to use that to your advantage. I think it took me a little bit of time to be able to understand that, but if you don’t have it, I think it’s so much harder. I felt that those guys were very approachable and that if you wanted to seek advice and help, they were willing. I don’t see as much of that in the world of tennis anymore.”

Australian players have a SPECIAL OBSTACLE to overcome if the want to be superstars: GEOGRAPHY

Australian players also have a special obstacle to overcome if they want to be superstars: geography. By simple virtue of where they’ve grown up, they are limited in how far they can extend their tennis unless they travel. While the champions of the ’50s and ’60s used to travel as a group and be away together for weeks on end, today’s players tend to base themselves in the Northern Hemisphere to make things a little easier. To Cash, that also explains some of the success the country’s current top two players have had.

“Lleyton and I are probably the only two that really came through as young, young players and were top 10 when we were still teenagers,” Cash says. “I think that’s got a little bit to do with our isolation and it’s no coincidence that the top two [today] – de Minaur and Popyrin – have been living in Spain.”

Because they are so far from home, though, the Aussies stick together, and their camaraderie makes a difference. Hanging out between matches, they look for home comforts, such as a particular coffee shop in Manhattan during the US Open, or ‘Australia House’ – a big home that Tennis Australia rents during Wimbledon where players, coaches and former stars are welcome. Good friends, and sometimes doubles partners, they help one another.

Doubles has been another key to the recent success. Thompson and Max Purcell won the US Open last year, while Ebden (with India’s Rohan Bopanna) picked up his second slam win at the Australian Open. Hijikata, Jason Kubler, Kyrgios and Kokkinakis have all won slams in doubles in recent years. Being on site at the back end of majors, thriving under pressure, has had a knock-on effect on their singles performances.

Winning a slam title is not the be all and end all, of course. A successful career is not entirely dependent on how many majors you win. But success breeds success and if one of this generation of players could somehow come through to win a big title, it would surely be an inspiration for the young players coming through.

De Minaur, perhaps the fastest player on tour and improving every year, would seem the most likely, but Popyrin has the big serve, a weapon that makes him a threat, as he showed at the 2024 US Open when he upset Djokovic in the third round.

De Minaur predicts Popyrin will now go from strength to strength. “He’s always had this big game,” he says. “But, for me, the way I’m seeing it is, in his mind, it’s clicked. It’s clicked exactly [what] his game style [is] . . . what he wants to do every time he steps on court. And he believes. So much in this game is about belief. I struggled with that belief, to take it to the next level. And I’m just happy to see Popyrin breaking through those barriers. And I think once you break through, you never look back. So, I think we were going to see some really, really great things.

This story appears in the Summer of Tennis issue of Esquire Australia, on sale December 9. Find out where to buy the issue here.