The most iconic cars on film

Just like actors, automobiles have a long and storied relationship with Hollywood. Here, we look back at the movies that helped transform certain cars into aspirational legends

CINEMA TOUCHES US in a variety of ways, through storytelling, escapism and ideas rooted in the human experience. So, when it comes to humanising its existence, the car owes a lot to Hollywood. There are few forms of popular culture that speak to the emotions cars can evoke: freedom, power, desire, romance and, yes, fear and horror. The car as a storytelling device is as old as the car itself, as is cinema’s evolving fascination with our relationship to the machine.

Cinema has always been enamoured by transportation. Horse in Motion (1878), the world’s first stop-motion film, might appear janky, but at the time, it was a highly technical clip of a man galloping on a horse. Seventeen years later came Arrivée d’un train à la Ciotat (Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat), in which a grand locomotive pulls into a French station. Apparently, the image of a train headed towards the camera was so shocking, it caused panic and terror among theatre audiences – remembering, of course, that this was the silent era.

And then came the car. One of the first movies to place the car within the context of modern, urban society arrived in 1906 with A Trip Down Market Street, which was filmed in San Francisco. American cinema pioneers the Miles Brothers attached a camera to a cable car to film a street scene. In one bustling 13-minute take, we see old cable cars and horse-drawn buggies appear alongside a flashy automobile, which winds its way through the traffic and performs mid-road U-turns as it threatens to take out oncoming traffic and unlucky pedestrians. It’s quite comedic to look back on now, but also an interesting glimpse at the development of a persistent Hollywood trope: cars represent the future.

The golden era of Hollywood and the rise of the automobile happened in tandem. With both came a new aspiration for status, rooted in power, consumption, attitude and freedom, particularly when it came to the bravado and potency of the American automobile, and the sophistication and panache of the British car.

Where would the car be without the iconography of James Dean, Elvis, Paul Newman or Grace Kelly behind the wheel? Would the Ford Mustang be the icon it is today without Steve ‘King of Cool’ McQueen’s raw, testosterone-soaked 10-minute car chase in 1968’s Bullitt, arguably the best car chase in cinematic history? What would Aston Martin’s marketing strategy look like if James Bond drove a Bentley (as he does in Ian Fleming’s books) instead of a DB5? Would Japanese cars and mod culture have gone mainstream without The Fast and The Furious franchise? Would the new generation of car lovers be quite as savvy had it not been for the beloved characters and storytelling of Pixar’s Cars (2006), a film that matched each vehicle with a human personality and values while shining a light on why so many people love motorsports?

Of course, many of these moments had clout behind them. Ford allegedly campaigned to ensure their vehicles were used solely as hero cars in Bullitt, which is why you also see McQueen in a Mustang and the bad guys smashing up General Motors’ Dodge Chargers. But still, the organic power of cinema has been pivotal in creating and perpetuating these myths.

But there’s a lesser-told story that helped to define the celebrity of the American car, and it has a lot to do with the fact that two of the most influential people in Hollywood and American automotive design were neighbours.

Harley J. Earl, head of design at General Motors and often described as the godfather of American auto design, and film industry pioneer Cecil B. DeMille lived next to each other in pre-World War II LA. They were also good pals, brought together by their love of cars. Not only did their friendship influence

how cars gained status among Hollywood elites seeking new ways to express themselves, it also informed the evolution of auto styling, which drew from the glamour of the mid-century LA lifestyle. Earl is credited with transforming the styling of General Motors’ dreamiest concepts and most futuristic cars, like the Corvette – a sports car that not only became the official ride of NASA’s celebrity astronauts but embodied all the American optimism, freedom and hedonism of the ’50s and ’60s. Just two years after its unveiling, the Corvette cemented itself as a cinematic sex symbol when it debuted in the iconic noir film and one of the blueprints of French New Wave, Kiss Me Deadly (1955). Characteristic of the era, it was driven by the film’s womanising, hyper-masculine protagonist, Mike Hammer.

Closer to home, Australian cinema’s most iconic road films like Wake in Fright (1971), Stone (1974), The Cars That Ate Paris (1974), The Rover (2014) and, in some ways, The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994), presented tough ideals of Australia against the backdrop our dusty, brutal landscape. They tapped into the deeply rooted link between the toxic masculinity found in Australian society and

our attitudes to car and motorbike culture. Before we were blessed this year with Furiosa’s appearance, this was also true of the series that put Australia on the global cinephile map: Mad Max (1979, original). One of the key legacies of this iconic series by George Miller and Byron Kennedy is how Mad Max answered the following question: if a car’s appearance can be used to project wider societal attitudes, can it also do so through being a character itself?

Savage, violent and highly ambitious, Mad Max was as much an antipodean commentary on the 1973-74 global oil crisis and rise of nuclear power as it was a parody of American car culture. Importantly, it upended the game and redefined what audiences thought was possible with a car as a central prop. The intimidating steed in question, the Pursuit Special (or the Last of the V8 Interceptors) is the kind of machine Australian petrolheads fantasise about: a psychotically modified and supercharged black Ford XB GT Falcon V8 muscle car – built in Australia no less. The Interceptor as both a character and a metaphor is as central to the lore of the franchise as Max himself. To this day, Mad Max has influenced wider Australian muscle-car culture more than any other film, its stunts and pursuits unsurpassed in their gritty brilliance.

Like Max’s Interceptor, we can’t talk about the car as a loyal sidekick without referencing James Bond. The Bond franchise, which turns 62 this year, positions the machine as an essential part of 007’s identity, along with his designer suits and penchant for martinis. In each of the 25 films, the Bond car possesses similar attributes to its actor-spy of the moment.

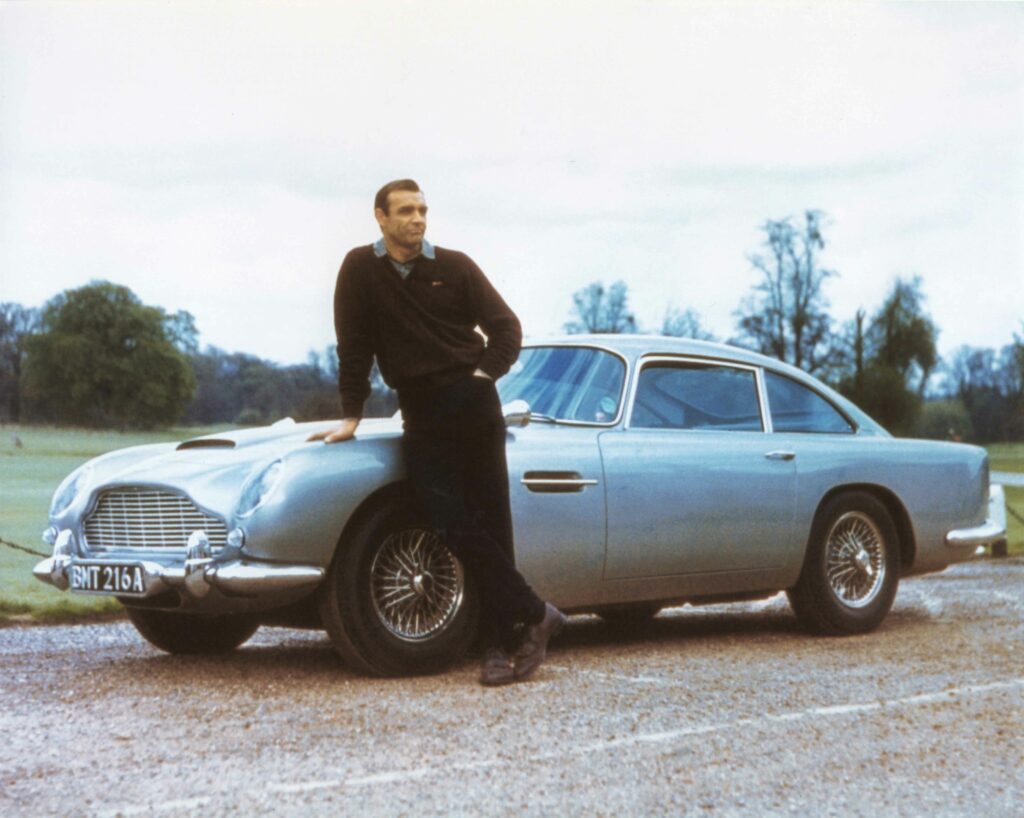

The most iconic Bond car is, of course, the handsome Aston Martin DB5, which made its debut in Goldfinger (1964). Like Sean Connery who first drove it, the DB5 is strong, with square shoulders and an understated air of smugness. “The DB5 is still the ultimate Bond car,” legendary automotive designer Ian Callum once told me. Callum is the man behind Bond’s Aston Martin Vanquish, Zao’s Jaguar XKR in Die Another Day (2002) and the shark-like Jaguar C-X75 villain car from Spectre (2015),among others. “The DB5 has a certain amount of restraint and elegance about it that really reflects a lot of what Bond is,” says Callum. “It’s about knowing. It wasn’t vulgar and it wasn’t loud.”

Similarly, Roger Moore’s wicked and wry wit was matched with the avant-garde 1976 Lotus Esprit S1 in The Spy Who Loved Me (1977), which looked like a speedboat and turned into a submarine (it was later purchased by Elon Musk, inspiring the Tesla Cybertruck). Then there’s Daniel Craig’s gritty, emotional and darkly intense Bond, a stark departure from the debonair and polished gentleman spy. While Craig has been behind the wheel of Connery’s DB5 more often than any other recentBond, it was the sleek Aston Martin DB10 in Spectre that set the tone for his character’s evolution. A masterpiece of understated power, the DB10 never existed in the real world – it was the first car developed especially for the franchise, and the first time we got a peek behind what a ground-up Bond car might feel like: classic, clean, timeless.

In stark contrast to how cars have been used elsewhere in cinema, the 007 altar of cool helped shift culture and automotive ideals away from the crudeness of muscle, grunt and gas, and into a place defined by good taste. If anything, the franchise has proved that horsepower can be highly refined.

Today, we have those who say, “You’re just into Formula 1 because you watched Drive to Survive”. But I’m old enough to remember when those same people claimed, “You’re just into cars because you watched The Fast and The Furious”. Throughout the 2000s, this street- racing franchise – particularly The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift (2006) – triggered a cultural movement. Not since 1973’s American Graffiti had there been a film about car culture so evocative – car clubs were born and mod-culture reigned, echoing the values and aesthetics of the film. Suddenly, those hand-me-down Japanese cars many of us drove here in Australia as P-platers became a canvas of cool potential.

For filmmaking, The Fast and the Furious isn’t to be sniffed at. The racing scenes that brought the nitrous-oxide injections to life – the machines, the combustion process, the exhaust and the flames – were boundary- pushing. Never had such intense accelerations been captured on film.

This style of filmmaking lives on. It has informed car advertising and marketing, while leaving a legacy that’s forged a new, cinematic style of car content popular on YouTube, Instagram and TikTok. Sure, the 11 Fast & Furious films are camp and clichéd, but their underlying charm is that the car isn’t framed as an alienating object of power but as something facilitating community.

As for the car’s place in cinema today, it seems the nostalgia and beauty of the automobile’s mid-century glory days still reign. As does the engine soundtrack, even if the car itself is an EV – I’m looking at you, Bullet Train and Confess, Fletch sound departments.

In real life we praise the serenity of the electric car, but there is something visceral about the soundtrack of an engine used to convey emotion in film. And unlike that flickering stop-motion horse of the past, we can’t see that appeal fading anytime soon.

Related:

The Road Trip: driving alfresco in Maserati’s Grancabrio

The best TV series, movies and documentaries to stream in October