"The opposite of comedy is misery": artist David Shrigley on drawing, tennis balls and the value of humour in art

David Shrigley is one of the world’s most acclaimed conceptual artists. As his sculpture 'Really Good' touches down in Melbourne for the NGV Triennial, he explains to Esquire the importance of humour in art.

DAVID SHRIGLEY WAS NERVOUS about his thumb making it to Australia unscathed. Not the digits on his hands—all going well, those will accompany the artist to Melbourne in early January. But rather, his six tonne, seven-metre high brass sculpture titled Really Good. It took about six weeks for the work to travel from Southampton in England to Port Melbourne, where it was dispatched; fans of Shrigley’s work could track the thumb’s every move via an interactive map on his website, which the artist illustrated himself.

“That shipping map kind of filled me with anxiety,” admits Shrigley, as he joins our call from his studio in Brighton, England. “I was thinking of that Richard Serra sculpture, which slipped off a container ship and into the bottom of the ocean on its way to New Zealand some years ago… and I was thinking, ‘Oh no, I couldn’t possibly lose the thumb into the sea’.”

If he weren’t so very British, his deadpan manner would make me question whether he was, in fact, stressed at all.

Fortunately, Really Good arrived at the National Gallery of Victoria on October 11, ahead of the hotly anticipated 2023 Triennial, which opened earlier this month. Melbourne is the second city in the world to host the monumental sculpture, after it was originally commissioned in 2016 by the Mayor of London to sit on the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square, which is one of the highest profile public art spaces in the world. With its comically elongated thumb—the type of gesture you might deploy when actually, things are not really good—the bronze work was intended as a comment on Brexit. But of course, its irony can be applied to all sorts of social and political circumstances. Given the year we’ve had, Australians are pretty spoilt for choice. And we’ll be able to project our feelings onto Really Good for quite some time—the work will be stationed outside the NGV until April.

The term ‘national treasure’ is bandied about rather liberally these days, but if this is your first introduction to David Shrigley OBE, let’s just say he’s absolutely one of Britain’s most treasured treasures. His interest in the “slippage” between language and image—the way visuals and text can work together to convey conflicting messages and feelings—has seen his “kind of subversive” illustrations of animals and everyday objects garner widespread acclaim in the global art world. But similar to rock-star artists like Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol, whose irreverence for traditional aesthetic standards meant they were shunned before they were celebrated, it could be said that non-conventional art fans were much quicker than mainstream critics to embrace Shrigley’s genius.

“I think there’s an assumption in the art world that comedy isn’t really acceptable,” ponders Shrigley. “Maybe that’s paying a bit too much attention to what art critics say… but it always seemed a bit like I was doing the wrong thing in the past. The drawings that I was making were sort of funny, stupid drawings. And it felt like a provocative act, or, you know, I felt like I was doing something that was not ‘serious’, somehow.

“I used to be embarrassed about the work being funny,” he continues, “but I always saw what I was doing as some sort of conceptual art. Like, I wasn’t interested in cartoons or comic books, I was interested in Duchamp and the Dada artists. I was interested in the ways words and images fit together, and it just happened that my voice was quite a comic one.” He says that now, he cares a lot less what others think. “I’ve probably embraced my sense of humour more; I’ve realised it’s okay to make works that are funny.”

Over the years, critics and collectors have warmed to Shrigley’s wit too. In April 2023, the print Shark Says, 2021, sold for close to $35,000 at auction in Japan. Scribbled around the drawing of a fairly ferocious looking shark are the words, “Shark says… Fuck you all.” Shrigley’s highest selling illustration, Untitled (It’s Ok), 2014, fetched almost $70,000 at a Sotheby’s auction in 2016. He clarifies that his work “isn’t comedy as such”, which would imply that “it has only one purpose, [and that’s] to make people laugh. But at the same time, I’ve realised it is totally fine to be funny.”

Dry and mildly existential in nature, it’s no surprise that Shrigley’s sense of humour travels exceptionally well on social media. The artist has over one million followers on Instagram alone, where he posts an illustration daily, often with no caption or accompanying context. Not that it needs it. Every time, people reply with thoughtful, insightful interpretations, as if responding creatively to a prompt. As charming and validating as the comments are, Shrigley isn’t one to read his fan mail. “It’s not something I like to do. It’s a bit like looking at your prostate or something… it’s lifting a rock and seeing all the potential unpleasant things—or potentially nice things—underneath. I’m happy to be in blissful ignorance when it comes to what people think about my work.”

Thumbs—of the giant bronze and flesh and bone varieties—aren’t the only things Shrigley is bringing to the NGV Triennial this summer. The Melbourne Tennis Ball Exchange, which is a version of the artist’s 2021 conceptual installation, the Mayfair Tennis Ball Exchange, will also occupy the gallery’s Great Hall during January. The work will begin with 14,000 new tennis balls, with the idea being that members of the public bring in their own used balls to swap with the fuzzy new ones embedded in the sculpture. (When I ask Shrigley if he’s aware the Australian Open will be on at the same time as his exhibition, he replies with a wry, “yes, obviously”. Turns out, he’s a big Andy Murray fan).

“I was feeling like the work I was showing in the gallery was a bit boring somehow… I felt like that static nature was something that I became a bit less interested in. So I wanted to make something that invited interaction,” he says of the propositional inspiration behind the tennis ball piece. “Consequently, many of the works I make these days require people to interact in some way, and there’s often a very bizarre reasoning to the way people react. Surprising things happen along the way.”

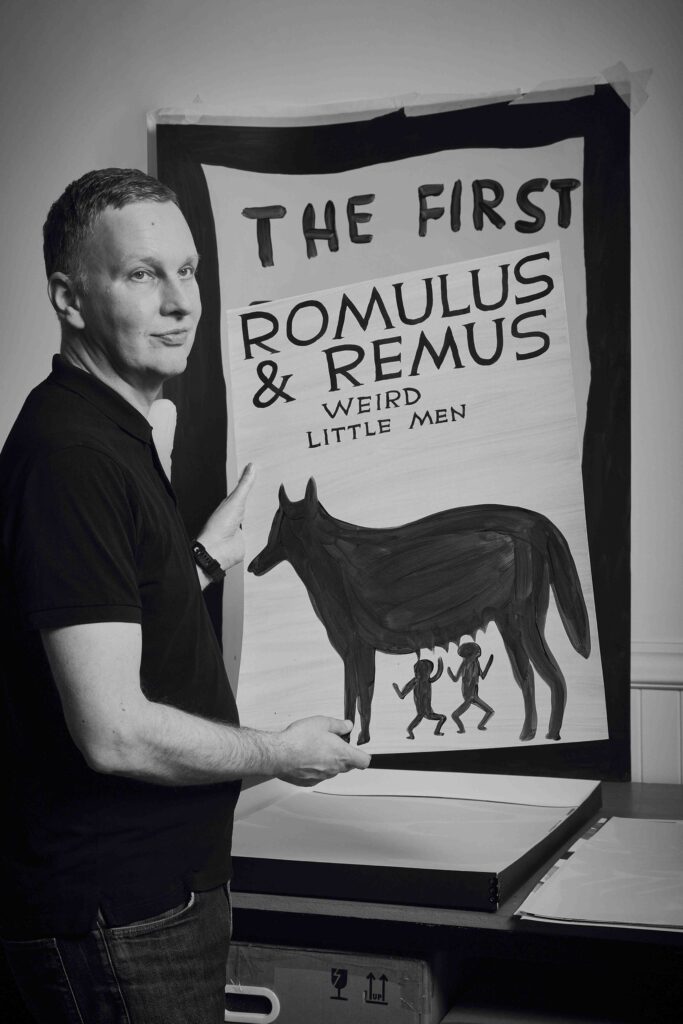

But drawing remains his life’s project; the vehicle through which he interrogates ideas about the world around us. This becomes abundantly clear as he guides us around his studio for this photoshoot—there are sketches at various stages of progress everywhere. What’s more, his initial motivation for putting his ideas on paper hasn’t shifted much at all.

“I just see the value of making art. I think everybody should be an artist and make art. I mean, you’re the same as I am, really… Even though I’m a fancy, famous artist, I’m still doing the same things as everyone else. I think a lot of people gain joy from art; the value it brings to people’s health and wellbeing is really underestimated, so it’s about facilitating that.”

Needless to say, people gain a great deal of joy from Shrigley’s art, whether it’s his pithy illustrations or large-scale installations.

“I think you have to remember that the opposite of comedy isn’t seriousness. The opposite of comedy is misery. And therefore, the opposite of seriousness isn’t just to be funny; the opposite of being serious is being not serious, like a dilettante.

“I think there’s something very special about comedy. It’s a gift that human beings have. I’m happy to have embraced it… Finally.”

Related:

Vincent Namatjira on humour, visiting the King and why fame is the aim

90 years of Esquire: the most memorable covers, stories and scandals