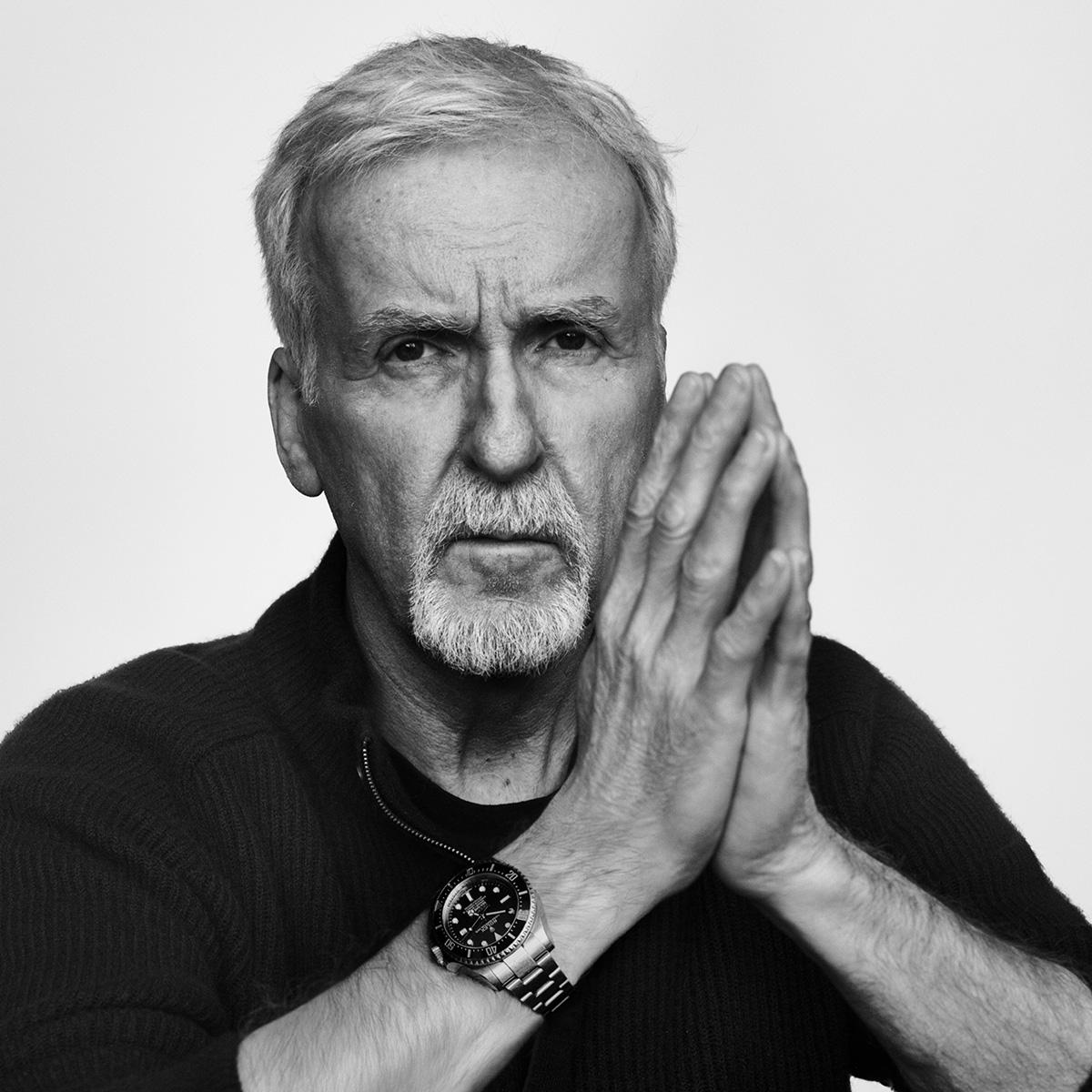

In the wake of giants: Tim Winton on why the climate fight isn't lost yet

In an essay for Esquire Australia, novelist and national treasure Tim Winton writes about his journey to becoming a conservationist, and why saving one whale species instils hope for a bigger battle ahead.

A SWELL LIFTS the boat for a moment. It hoists us and tips us gently in our seats. And as it rolls beneath us and travels on to break across the coral reef behind us, it sends up a hissing curtain of spray that hangs in the air, sending rainbows across the clear turquoise water. Once the vapour subsides, the hot, tawny terraces of the Cape Range onshore come into focus. Over the ancient peninsula a heat haze shimmers.

The motor growls, the boat surges forward a little quicker.

Out beyond the reef front, just west of us, there’s a blast of spume.

The shining backs of two humpback whales break the surface.

John steers us parallel, lifts his crossbow and calls for a photo.

I hoist the big lens, find the animals in the viewfinder and start snapping.

I focus on the dorsal fins, memorising the differences between them. The closest animal has a fin with a modest curve and a filigree of white pigment on its trailing edges. The whale alongside it, a few metres beyond, has a sharper version, all black.

They take a shallow dive – you can tell by the slightly flat entry – and John maintains our course parallel to their northward track. They’re not in a hurry, these animals, but they swim with the preoccupation of incomers.

These whales have just migrated 5000 kilometres from their feeding grounds off Antarctica. Out on Ningaloo Reef, in early winter, their disposition is distinctive. Sometimes, it’s as if they have tunnel vision. Their innate curiosity seems dampened. Because they’re on a mission. They need to reach their resting grounds in the tropics where many females will give birth and feed their calves. Places like Camden Sound in the Kimberley and Exmouth Gulf, just around the corner from Ningaloo Reef. In those sheltered waters, they’ll socialise and recuperate for the rest of the winter.

There’s another reason for them not to tarry out here in open water. Because for the last few weeks, orcas have been coursing up and down the 300-kilometre reef. These sleek killers have swung down from the northern Indian Ocean, as they do every winter, to meet the annual migration and pick off calves born on the journey.

In a few weeks’ time, once these humpbacks are relieved of the imperative to get inshore to safety, they’ll be like different animals. On the other side of the Cape, in the quiet refuge of Exmouth Gulf, they’ll be relaxed, sociable and so curious they’ll be hugging the boat, leaning across the coamings to check us out. But out here on the reef, they’ll swim straight past.

Right now, like all the others out here, the pair we’re following are hugging the reef edge for cover and using the familiar bathymetry, where the deep suddenly meets the land’s edge, to navigate a path to safety. Ningaloo is a distinctive marine environment. This is where Australia’s continental shelf is shortest, where the distance between the shore and the abyss is vanishingly narrow.

“The animal gives a massive tail swipe and sends a shining arc of spray into the air.”

My friend John Totterdell is a winter fixture at Ningaloo. This wiry, gregarious bloke, with his head wrapped in a white towel like a Japanese fisherman, is a prominent cetacean researcher whose scientific papers are widely cited. But he’s something of an anomaly.

“I don’t have a PhD,” he says. “I don’t have a degree.”

For many years, John was a tuna fisherman on Western Australia’s south coast. Back in the ’80s, when it was clear the flagging southern bluefin tuna fishery required much more research and higher levels of management, he began taking scientists from the CSIRO and Japan’s NRIFSF out into the Southern Ocean to do tagging work to monitor fish recruitment.

“That was the beginning of my science world,” he says. It was a turning point in his life. He still helps with tuna surveys. But nowadays whales are his main preoccupation. He works mostly with humpbacks and orcas. “I’m enchanted with these animals,” he says. “There’s an intelligence there you don’t always see in other animals.”

In summer, he works off the famous Bremer Canyon, in the Southern Ocean, and as he says, “For the last fifteen years, I’ve migrated up to Ningaloo with the humpbacks.”

John thinks of these humpbacks as locals. After all, he says, they only spend a short stretch every year feeding down in the ice. The rest of the time they’re either here or on their way. And when you learn they have their calves in Exmouth Gulf – otherwise known as Ningaloo’s nursery – and nurture, and socialise them there, you see his point. Even if you’re a wayfarer, that’s the kind of stuff you do at home.

The radio squawks. It’s Tiffany Klein overhead in the spotter plane. She tells John she’s south of us, tracking several more animals headed our way. He thanks her, juggling the wheel, the radio receiver and the crossbow all in the same moment. Which sounds impressive until you see him add a mobile phone and a sandwich to the equation.

For a few seconds our humpbacks are lost in the glare. Then we see the distinctive ice-turquoise flash of underbelly just ahead. It’s followed by a strange subsurface unfolding of water, which is the animal’s bow wave.

John puts on some revs. And the moment the closest whale surfaces, exposing its gleaming flank, he lets fly.

I keep my finger on the shutter button as the dart whips across the water, hits the whale high on the shoulder and bounces back into the water. A perfect shot.

The animal gives a massive tail swipe and sends a shining arc of spray into the air.

“Male!” we both yell at once.

After twelve seasons of taking tissue samples to check the health of the population and the state of the southern ice, John has noticed something distinctive and peculiar, which isn’t easy to understand. Because while most females – particularly those with calves – will barely register the dermal nip of a sampling dart, most males will react in ways that are unmistakeable and the histrionics on display this morning are common.

I make the obligatory dad-joke about thin-skinned males and John wheels the boat around to retrieve the sample.

The dart has a hollow tip. Behind that is a buffer. This restricts penetration and causes the dart to bounce back away from the animal. It also helps keep the dart and the tissue sample afloat.

Down at the transom, I scoop it from the water while John gloves up. The tip of the dart is like an apple corer and from it droops a pale worm of blubber. Deeper inside the tip is a black layer of skin.

John unscrews the tip, drops the sample into a vial and sets it in the cooler. He takes out a new tip, disinfects it and winds it onto a dart. Then we’re off again to get a biopsy from the second animal.

Fifteen minutes later, we meet the pod that Tiff has tipped us off about. We sample six animals that day. In between, we talk about our grandkids, the prospect of a surf later in the week and the whereabouts of John’s beloved orcas.

“Australians are proud that we pulled up at the last moment and got it right in terms of whaling.”

Over the years, I’ve spent many hours on the water with John and Ningaloo’s whales. Because I enjoy the company of both. I get a kick out of the unlikeliness of his personal trajectory – the everyman with whom scholars from all over the world collaborate and to whom they send graduate students – and I’ve learnt a lot about the animals from being out there with him. That’s important to me because whales are integral to my personal journey too.

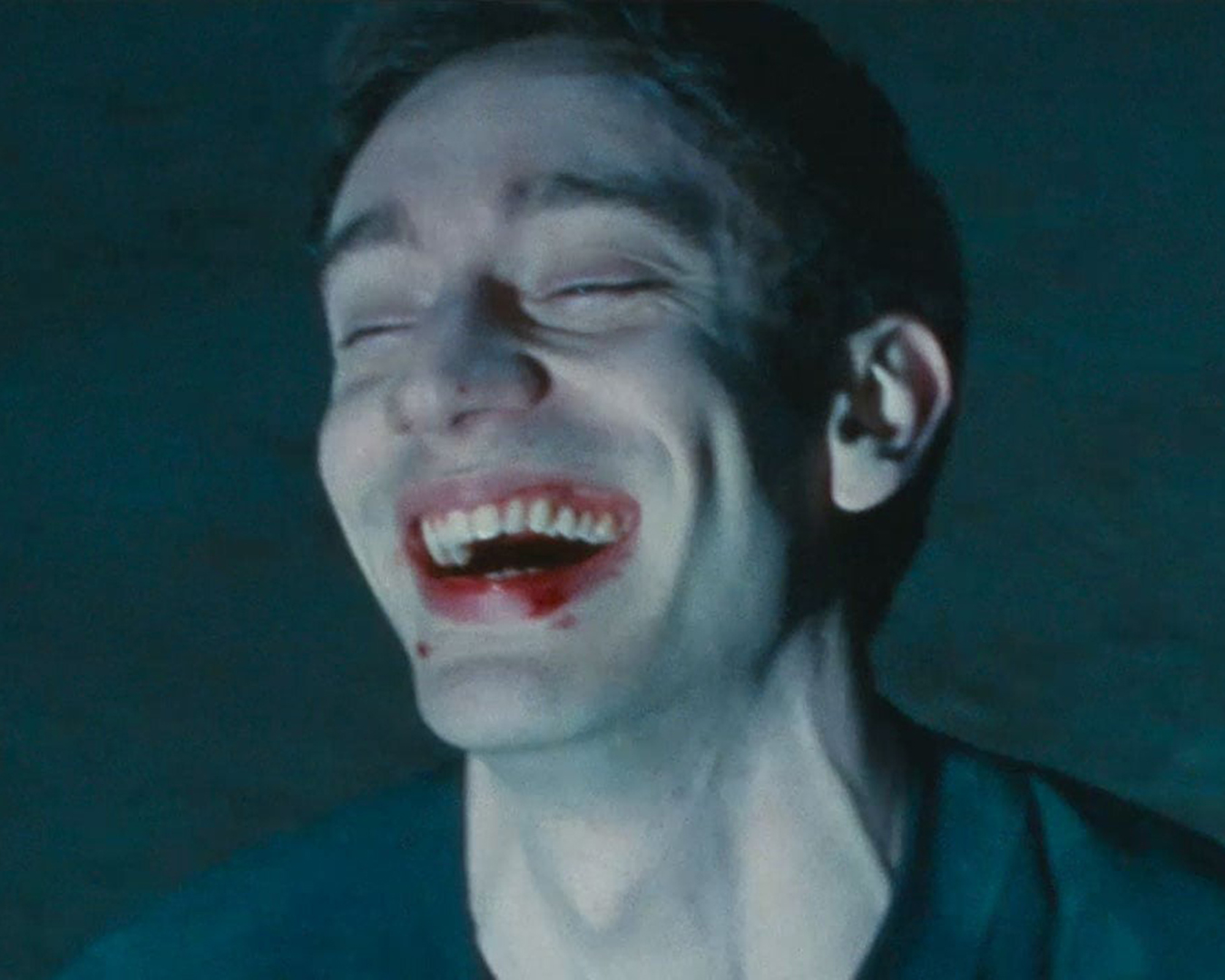

As a teenager, I lived in Albany, Australia’s last whaling town. The sight of a sperm whale having its head sawn off and its blubber ripped away is appalling. The experience doesn’t get easier to digest with repetition, believe me. I can still see the avalanche of intestines, the sharks twisting through the rivers of blood that spilled out into the bay from the foot of the flensing deck. The stench of boiling fat. greasy steam that settled in your hair, on your skin and clung demonically to the hairs up your nose. It was, truly, a scratch-and-sniff Hieronymus Bosch.

But what appalled me most, encountering this as a teen, when whaling was just another bit of business as usual, was knowing this was being done to a species on the brink of extinction. That bit of information was hardly even contested. The pigheadedness of this industry, still drunk on its own romance, was bewildering. It was trading while ecologically insolvent. And it knew it. Still, it was determined to plough on anyway. The scruffy greenies who found their way to Albany in the 1970s to stop it, were reviled as alarmists and fools. Nobody’s denouncing them now.

Watching all that drama and conflict and bullshit – up close and from afar – was a foundational experience for me. I’m glad I witnessed it. Because it steeled me for the mulish intransigence of the fossil fuel industry forty years later. That’s another industry clinging to its romantic past, an older dispensation, when oilmen called the shots and everyone fell in line. It tries to keep that dying empire alive with a palliative web of spin and deception.

But neither scruffy young folks nor investor groups are buying it. They know ecological insolvency when they see it.

The Secretary General of the UN, with the full backing of the world’s climate scientists, says that in order to keep our planet’s warming to 1.5 degrees, no new fossil fuel projects should progress. In the face of the science, the oil and gas industry cracks on.

The fight isn’t about whales anymore. The struggle before us concerns the very conditions of life. The air we breathe. The state of our oceans. The food we eat.

Whalers made me a conservationist. It wasn’t the gore. It was the industrial-scale stupidity. That was my first exposure to the self- destructive magical thinking that infects businesses and governments when they’re terrified of facts. When they’re staging a fighting retreat in the face of change and accountability.

When commercial whaling finally ceased in Australia in 1978, there were only 300 humpbacks left in the western Australian population (Population D). As a teenager, I saw a single live specimen. Think of that. In 1000 days, one humpback! Nowadays, I can see fifty in a morning at Ningaloo. The noise of the buggers after dark in Exmouth Gulf can keep you awake half the night.

Between 30,000 and 40,000 now travel up the west coast every year. It’s the biggest conservation success story in my lifetime. A benchmark. And a heartening precedent.

There are more whales and yet their economic value increases every year. Live whales create more jobs in Australia than whale killing ever did.

Australians are proud that we pulled up at the last moment and got it right in terms of whaling. And they should be.

This story of change and resurgence is emblematic for me. It’s a source of hope. It shows that we can break through the deadly inertia of business as usual. With determination, good science and vigorous public education, we can produce the cultural change required to pull species, including our own, back from the brink of oblivion.

Whaling didn’t stop because businesses and governments suddenly saw the light. It happened because citizens – scientists, community groups and in particular, thousands of young people, many of them school children like me – pressed something rotten to their faces and made them do something about it.

With whaling, we saw past the toxic romance of business as usual. With the climate emergency, we’ll do it again.

Every time I see a humpback breach at Ningaloo, I’m convinced of it.

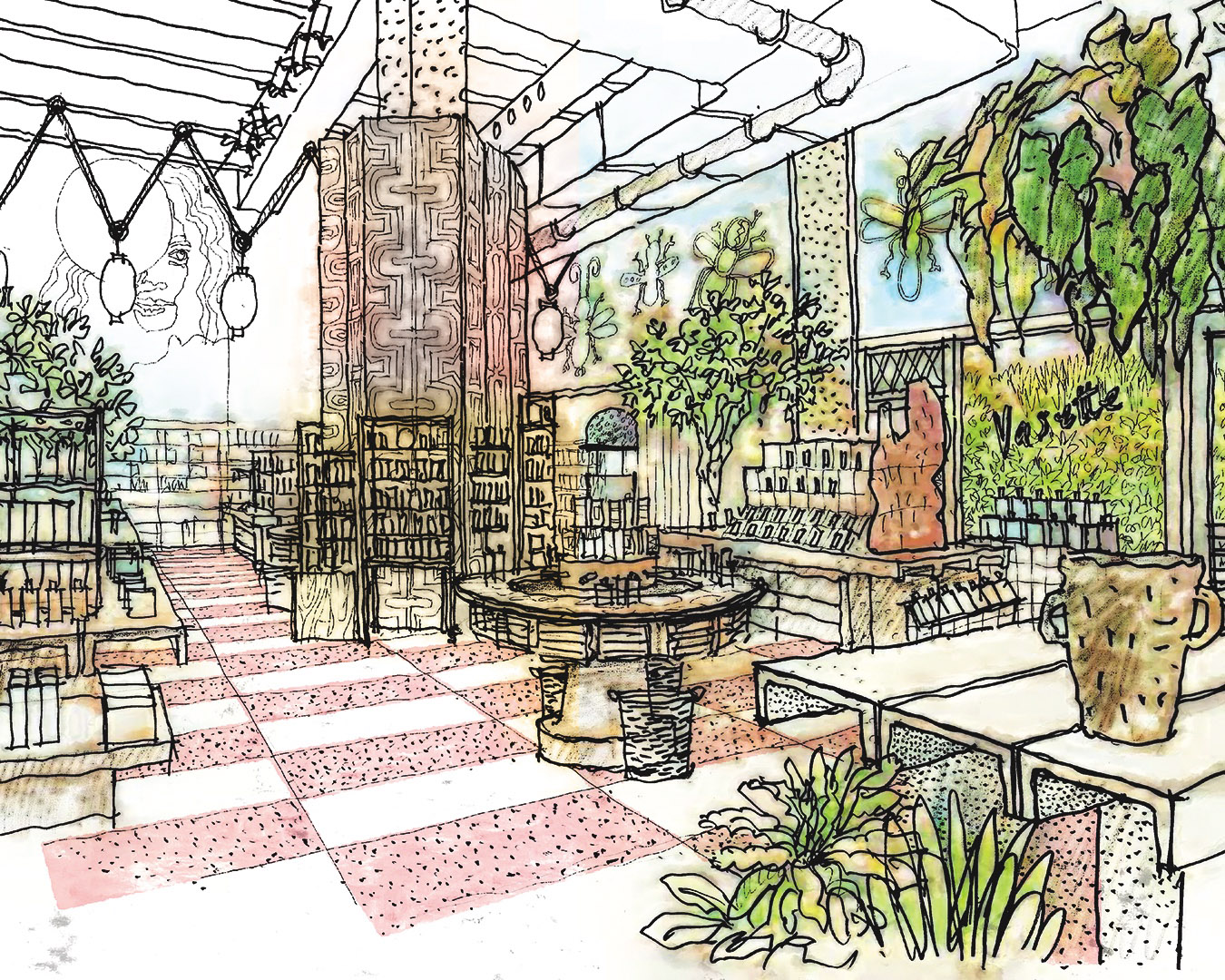

Want to know more?

Dive into a world treasure with its most prominent defender as your guide in Ningaloo Nyinggulu. Written and narrated by Winton, this stunning science-based nature documentary series tells the remarkable story of Ningaloo, one of the last intact wild places on our planet.

Over three episodes filmed in remote Western Australia, Winton shares the wonders of the place that’s inspired his work for decades, joining Traditional Owners, scientists and other experts to understand how Ningaloo endures as a mighty global lifeboat of biodiversity and showcases why it is a beacon of hope in the face of an extinction crisis and climate emergency.

Ningaloo Nyinggulu is produced by Artemis Media and is available to watch on ABC iview.