How to turn your home into a sanctuary of health

Wellness by design

THE WORD WELLNESS must be having an enormous identity struggle. It began life as the simple opposite of illness, but over time it has come to encompass everything from juice cleanses to a regimen of supplements to cashmere throws, its net cast so wide it seems limitless. And despite the occasional PR disaster (Belle Gibson), it forges on.

And now wellness has found its way into architecture, where the eternal distinction between house and home (house: physical space; home: place of psychological peace) feels especially relevant.

A 1986 article in The Journal of Environmental Psychology noted that “our conscious perception of home is directly influenced by our social nature within the space, more than by the physical makeup from which these interactions may take place”.

And yet, in today’s wellness boom, homes feel less about entertaining and social connection, and more about solitude and self-preservation. The television as the focal point of most living rooms is a telling symbol of our domestic priorities. Partly, perhaps, that’s a relic of COVID, but is it really? I’d argue that the wellness boom, which predates COVID, has tended to isolate us rather than connect us.

I grew up in an Italian household where ‘alone time’ was a foreign concept. Our home was a constant hum of visitors, rowdy lunches, big parties with accordion players and the regular sharing of enough food to feed a small country. It was the opposite of today’s pared-back version of wellness, yet it was wholesome, stable, rooted in culture and undeniably alive.

The wellness era of architecture, however, leans towards self-preservation. Gone are the days of the rumpus room – in its place, sanctuaries for the self. Homes today are designed less for community, more for solitude.

Visually speaking, the wellness movement in architecture doesn’t move me. I’ve admired chic gyms and elegant ice baths, but I’d take a moody bar or a cosy library any day.

When I was writing my thesis at university, I became obsessed with Le Courbusier’s Unité D’habitation in Marseille. Built after World War II to address France’s housing shortage, it offered private apartments alongside collective amenities: a kindergarten, shops, gym, pool, outdoor cinema. Four years overdue and well over budget, Unité d’Habitation was a towering concrete structure that would go on to become one of the most influential buildings of the 20th century.

Le Corbusier’s vision was a fantasy world where occupants would never need to leave. It was, in essence, a wellness fortress – post-war anxiety made concrete. The only problem? Humans aren’t built for isolation. Connection, culture and chance encounters are what keep us alive. And so Unité d’Habitation, for all its innovation, faltered. The human element had been forgotten.

Now, in our post-COVID wellness world, we’re all about the self. And while a commitment to wellness may (or may not) give you a few more years at the end, and may (or may not) temper your cortisol levels and improve the quality of your sleep, its flip side could be a life that too often feels barren, grey, unfulfilling and, ultimately, lonely.

Take the American biohacking venture capitalist Bryan Johnson, who is preoccupied with anti-ageing and longevity. He starts his day with 54 supplements and an hour in the gym. He eats only between 6am and 11:30am and goes to bed at 8:30pm every night. Between his last meal and his head hitting the pillow, he ingests more than 100 pills and bathes his body in LED light.

Now, the chances of Bryan and I sipping martinis together and discussing the psychological relationship between architecture and wellness are slim at best, the slimmer still for his strict bedtime and aversion to alcohol. Perhaps, to Bryan, his life feels full and his house is a home. But, for me, a life without martinis, steak frites and long, late nights with friends isn’t one worth living, let alone extending.

Likewise, for you, perhaps wellness at home needn’t mean a colossal TV and a sauna crammed into a city apartment. It could just as easily mean a martini station in the lounge, a tottering pile of books or a deep chestnut-coloured couch that makes you want to stay up all night playing cards.

Take the late Anthony Bourdain (someone I actually would’ve loved to have a martini with). While he may have had his demons, he certainly encouraged a life of exploration, indulgence and connection. To quote him: “Eat at a local restaurant tonight. Get the cream sauce. Have a cold pint at 4 o’clock in a mostly empty bar. Go somewhere you’ve never been. Listen to someone you think may have nothing in common with you. Order the steak rare. Eat an oyster. Have a negroni. Have two. Be open to a world where you may not understand or agree with the person next to you but have a drink with them anyways. Eat slowly. Tip your server. Check in on your friends. Check in on yourself. Enjoy the ride.”

Much like Le Corbusier, the wellness industry often forgets we’re human – and all gloriously different. Maybe you’re more Bryan than Bourdain. For me, it’s somewhere in between (though definitely leaning Bourdain). My home may be equipped with a fully stocked bar and a martini service worthy of a high-end hotel, but I also indulge in wellness-adjacent luxuries: long soaks in the tub, a vast Baina bath sheet to wrap myself in, a burning Trudon candle to inspire calm, an ever-growing collection of teas, and lemon trees in the garden (perfect for hot lemon water, or a gin and tonic). In the end, it’s about balance – and about you.

If your home is starting to feel more like a house, then maybe it’s time to show the wellness industry to the door.

Related:

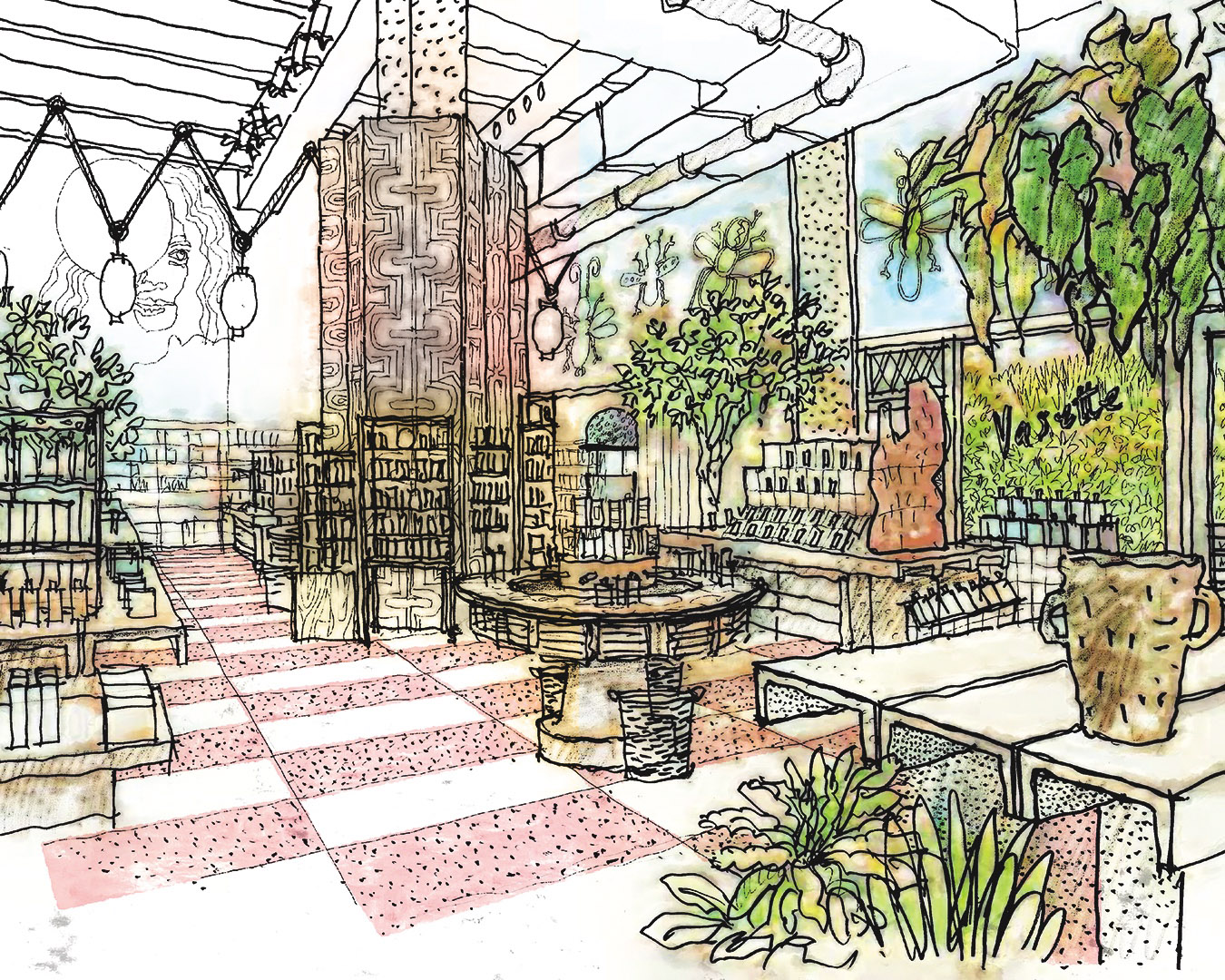

Retail therapy: how wellness became the new frontier of bricks-and-mortar shopping