Why is homophobia in male sports still an issue?

Last week’s Four Corners investigation into homophobia in the AFL should open up discussion on the culture and attitude of men’s sports across the board.

THERE WAS A scene during last week’s Four Corners investigation into homophobia in the AFL where the league’s CEO, Gil McLachlan, talks about the burden that would befall the first player in the league to come out as gay or bisexual.

Much was made of the use of the word ‘burden’, both in the episode and in the commentary in media and online afterwards, the main thrust being that it was indicative of a problematic, possibly immature culture in the organisation that starts at the top. If that is the attitude of the CEO, then is it any wonder that no player has felt safe to come out, leaving the AFL as the only professional men’s sports league in the world not to have ever had an openly gay player. This is despite the AFL supporting the “Yes” vote in the marriage equality plebiscite and winning the Pride in Sport Organisation of the Year in 2017.

As openly gay amateur footballers in the episode and others have since pointed out, it is a burden, in the truest sense of the word, to be forced to hide your sexuality and deny an essential part of who you are to the world.

While McLachlan’s choice of words was undoubtedly poor, there may be some truth to what he was struggling to articulate. Truths that don’t reflect well on the league or its fans.

There is no denying that the first AFL player who does come out as gay will face incredible challenges. They will find support from the league and most likely their clubs. Of that we can be reasonably certain, for there is simply too much for the AFL to lose if it does not support a gay player to the hilt. What is less certain is how a not insignificant section of fans will react. Because as the continued abuse of Indigenous players shows, there is a corner of AFL fandom that can be toxic.

The treatment of Adam Goodes in the last two years of his career remains a stain on the game. Nearly a decade later, you wouldn’t expect the same kind of hostility from fans in the stands towards an openly gay player, though it can’t be ruled out. The fact that Goodes wasn’t widely booed until he started attempting to use his platform to advance the cause of his people, shows that much of the abuse he received was racially motivated.

There are penalties for racial vilification for both players and fans but these days the grandstand is not the primary forum for abuse. It is online and on social media. Earlier this year, Brisbane Lions’ Charlie Cameron, Fremantle’s Michael Walters and Nathan Wilson, and Adelaide’s Izak Rankine, were all racially vilified within a 48-hour period on social media, while The National Indigenous Times reported back in April that there had been 23 reports of racist abuse towards players across the AFL, VFL and Talent League this season.

An openly gay player would undoubtedly face online abuse. But they would also be flooded by messages of support. We know this because there is a similar precedent in the round-ball game. In 2021, Adelaide United’s Josh Cavallo became the only openly gay professional footballer currently playing in the world. I spoke to Cavallo last year on his decision to come out. He too, spoke of the burden of not being able to be himself, something that hit him hardest at a ceremony where he was awarded the A-League Rising Star award. “Everyone was ecstatic that I got this award. I was happy on the outside, but on the inside, I was really sad, because I couldn’t show them the real Josh, who I truly am. That really hurt. And that was the moment where it sparked. I wanted to change. I wanted to be myself and let the world know who Josh Cavallo is.”

In October that year, four months after that awards night, Cavallo decided to announce his sexuality to the world via a moving Instagram video. In doing so he followed in the footsteps of Englishman Justin Fashanu, who came out in 1990. Among the other Australian codes, Cavallo joined former rugby league star Ian Roberts, who declared his sexual orientation in 1995, as the only players to come out while playing at the highest level.

Cavallo was swamped by messages of support from fans and fellow footballers, his post receiving over 700,000 comments in 30 minutes. In May last year 17-year-old Blackburn FC player Jake Daniels came out, crediting Cavallo as his inspiration.

“I wanted to take that next step and be myself and be that first person that does this,” Cavallo said. “There are kids now that are nine, 10 years old that could find out they’re gay and say, ‘Okay, I don’t belong in football, I don’t belong in sport’. Now they might look at it and say, ‘Oh, there’s Josh. I can definitely be successful and play football’.”

Of course, as well as the outpouring of support, Cavallo copped abuse, as he knew he would. It didn’t deter him. “I can take it. Being the first one, I’m going to experience a lot of hate, but I’m taking the stigma away… It’s unfortunate, but I have to go through this stuff to make it easier for the next generation.”

That is a taste of what could lie ahead for any AFL player that chooses to come out, although you would have to say the spotlight and scrutiny would likely be more intensified in the AFL-mad southern states.

And while Cavallo was followed by English player, Jake Daniels and a couple of others in leagues below the top flight, there hasn’t been a Premier League player since Fashanu.

Similarly, since Ian Roberts came out in the 1990s, not one NRL player has subsequently done so. Roberts’ case stands as a both a remarkable outlier and tribute to the man and his fortitude, as well as a sad monument to the culture of the NRL.

Roberts had a reputation as a hard man, one of the toughest players in the NRL at the time. If he was abused by fellow players, he wouldn’t hesitate to take them on. Abuse from the crowd was something he had to wear, but like Cavallo, he could take it. If Roberts were to come out today, he would likely become a folk hero, the type of player kids would aspire to emulate. It’s a shame that in the darker days of the ’90s, the NRL and its fans weren’t ready to fully get behind him.

In some ways Roberts’ case has allowed the NRL to get off the hook in terms of its attitude towards homophobia. The fact that no players have followed Roberts speaks to the same kind of cultural issues the AFL faces. Last year, seven Manly Sea Eagles players refused to play in a match based upon the team’s decision to wear LGBT pride themed jerseys.

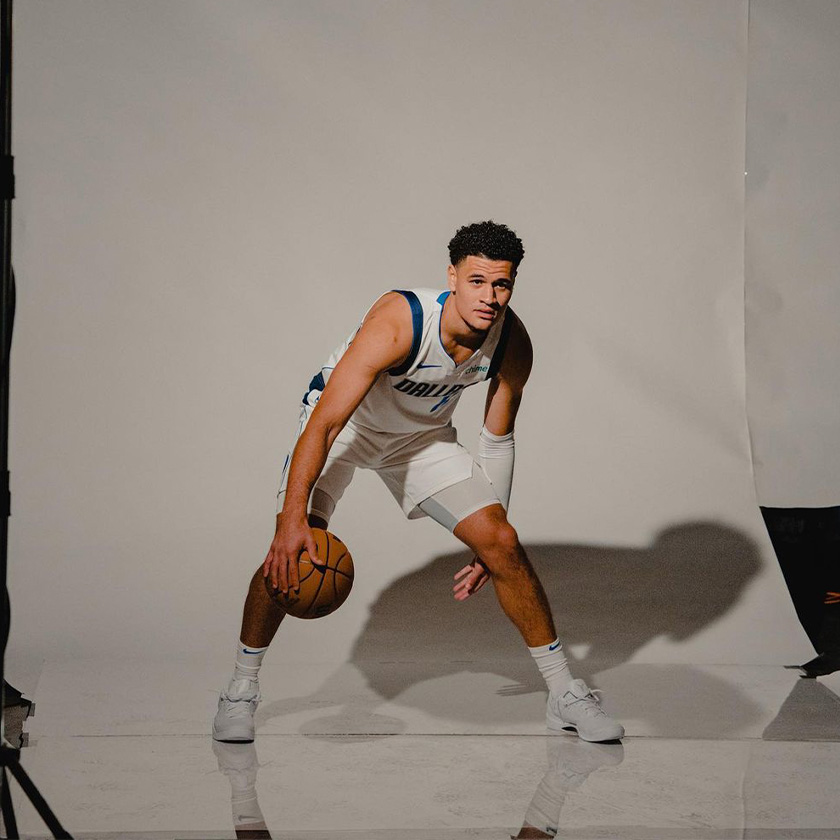

In basketball, meanwhile, Adelaide 36ers player, Isaac Humphries, came out in November 2022. Yet in January, the Cairns Taipans refused to wear jerseys celebrating the NBL’s inaugural pride round, arguing they were protecting an unnamed player or players in the team who had been abused after reports of their hesitation to wear the uniform on religious grounds surfaced.

Once again, like Roberts, Humphries’ decision to come out has not seen others follow in his wake. The reasons for this are complicated. Some players may plan to do it at the end of their careers when they would likely face far less attention, scrutiny and abuse, though not if the case of Danielle Laidley, formerly a player and coach for the Kangaroos and the first transwoman in the AFL, is anything to go by. Laidley, who is the subject of an upcoming documentary, was publicly outed by Victoria Police officers when she was arrested on drugs charges and has since been targeted on social media.

Or it could be that there are just not that many gay players in male sporting leagues because the culture of these sports and lack of role models means many young gay men opt out of sport early, never progressing to the elite ranks, in a self-perpetuating cycle.

One player manager told Four Corners reporter Louise Milligan that he had heard that the percentage of gay men in the AFL is lower than in the general population. The manager speculated that there might only be up to five players out of the 850 in the league who are gay.

A study in the Annals of Behavioral Medicine found gay and lesbian and bisexual teenagers were 46–76 per cent less likely to participate in team sports than heterosexual teens. The authors write: “For males especially, being involved in organised sports—specifically contact and collision sports—is both a primary means of establishing oneself as being more masculine and a means of internalising traditional gender role norms. From an early age, boys identify with athletes and immerse themselves in informal and formally-organised sports activities as a means of asserting their masculinity. Homophobia is often used to socialise and police conformity to traditional gender norms.”

Another study of adults in the Netherlands found that gay and bisexual men were less likely to participate in competitive team sports than heterosexual men but that sexual orientation differences were less pronounced in women.

The fact that the Four Corners episode aired the night after the Women’s World Cup final brought the distinction between attitudes between men’s and women’s sports toward sexual orientation into sharp relief. The tournament featured many lesbian players, including 12 Matildas. Similarly, half the captains in the AFLW are lesbian. The reason for this disparity is clear enough, as writer Rebecca Shaw wrote in the wake of the tournament and the Four Corners episode last week: “Take away all of the defensive arguments and the silence and the deflection around this issue, and all you have left is obvious, pervasive homophobia. There is no reasoning it away when it is so clear that the expectation to keep personal lives private does not apply to heterosexual players.”

That’s true and it’s the sad reality of men’s sports in Australia and overseas. And while the AFL waits for its own Ian Roberts, Josh Cavallo or Isaac Humphries, what really needs to happen is the type of systemic cultural change that means it is not such a challenge for the player who decides to come out. Until that day arrives, we should keep supporting Cavallo, Humphries, Roberts and any others who follow them. And, in the wake of the WWC, continue to get behind women’s sport.

Related:

Why isn’t drug-testing of athletes the same across all sports: an explainer

The Ted Lasso effect: why American celebrities are taking over English football