Generation K: How a party drug could be the silver bullet for depression

Ketamine is that rare drug that lives in the ER and the dance floor - but could it be used for mental health?

IN THE EARLY HOURS of a Sunday morning in 2015, Emma (not her real name) – a then 23-year-old nursing student – perched at the end of a driveway on a sleepy street in Wollongong, NSW. But where trees, double-storey houses and letter boxes should have been, Emma saw a “Legoland” – uncountable coloured plastic blocks, stacked and shaped into the silhouette of suburbia. “I felt like I was a Lego person,” she recalls.

Just before Emma had been transplanted into toy town, a friend had offered her a thin, powdered line of ketamine. It was Emma’s first time using the drug, which she snorted, and it produced a feeling, she says, that was “unusual and kind of fun, but not something where I was like, I need to do this again.” After a few hours spent hallucinating children’s blocks, Emma fell asleep. When she woke up sometime later, she was back in her bricks-and-mortar reality.

Seven years later at a house party in Melbourne, by now 30 and a qualified nurse, Emma was offered a “massive” line of what she was told was cocaine. She’d done coke before and knew how the drug should hit, but this felt different. The friend who distributed it looked panic-stricken, realising in that moment she’d mixed up two bags of pale powder and accidentally given Emma ketamine. The next minute Emma was on the couch “in a K-hole” (a dissociative state that can occur after a high dose of ketamine, where people can be conscious yet unable to move or respond).

Trapped inside her own body, she was living out a nightmare. “I hated it,” says Emma. “Everyone else who was microdosing was having fun but not sedated. I was in this middle, horrible place.” Eventually, she managed to twitch a finger, unlock her phone and call her girlfriend, who arrived in an Uber and shepherded her out. Once safely inside the car, Emma wept.

At its most basic, ketamine is a short-acting dissociative anaesthetic, developed for use in human and veterinary medicine. Its role is to block key glutamate (NMDA) receptors, producing feelings of detachment from the body and surroundings, numbness and altered perception. In hospitals it’s an ER workhorse, bought as clear liquid in sealed vials. On the street it most often turns up as a white crystalline powder that’s crushed and snorted, sold for around $200 per gram.

But there’s a third, more discreet deployment of ketamine – the same drug that levelled Emma – that has been building momentum over the past few decades, offered in speciality clinics in supervised doses to people whose depression and anxiety have resisted conventional treatment. It’s this double (or triple) life that makes ketamine both a cultural Rorschach test and one of the most debated molecules in modern wellness.

“It’s often called a horse tranquilliser or a party drug,” says Dr Adam Bayes, psychiatrist and senior research fellow at the Black Dog Institute. “But it is used day in, day out in general hospitals for anaesthesia.” In much lower, carefully titrated doses, Bayes says, ketamine, or its cousin esketamine (a ketamine derivative delivered as a nasal spray), can help people with treatment-resistant depression – the cohort that hasn’t improved after multiple standard antidepressants.

Of the estimated one million Australians who’ve experienced a depressive episode in the past 12 months, Bayes says around one third “don’t respond to multiple trials [or] standard treatments”. “There’s good evidence in treatment-resistant depression,” he says of the drug. In a 2023 British Journal of Psychiatry study led by UNSW Sydney and the Black Dog Institute, bi-weekly injections over four weeks led to full remission for more than one in five participants, with about a third experiencing a 50 per cent or greater amelioration of symptoms. “Effects can appear within hours, which matters if someone is suicidal,” Bayes adds.

But access comes with strings. “You would need to have tried, and not had success, in treatment with a number of other antidepressants available,” says Bayes, who also cites cost as another barrier to entry. In May, Australia listed esketamine on the PBS, slashing the pharmacy cost of the drug. But the catch lies in how it’s administered: by law, ketamine doses must be given in-clinic (Black Dog has several dedicated ketamine clinics across Australia), followed by two hours of monitoring for possible side effects that include dissociation and blood-pressure spikes. And there’s no specific Medicare item yet to cover that time and labour, which can cost the recipient anywhere between $300-$500 per session. “It’s an equity issue,” Bayes says. “The drug might be affordable, but the visit isn’t.

Prescription is also not a foregone conclusion. “We don’t just run a ketamine clinic and then everyone that comes to the clinic gets ketamine,” Bayes says. “Personalising the treatment to the individual is very important.”

KETAMINE, ALONGSIDE OPIOIDS, cocaine and cannabis, is a Schedule 8 Controlled Drug, meaning its off-label psychiatric use is legal but squarely the prescriber’s responsibility. The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) declined to reschedule ketamine in 2023 and says it isn’t considering a change. And a spokesperson for the Department of Health, Disability and Ageing told Esquire that off-label use “is not illegal” but is a “unique clinical decision” requiring informed consent. It’s a similar story in the US: use is supervised (take-home is not allowed) and the FDA has specifically warned against compounded at-home ketamine for psychiatric use.

Schedule 8 substances are also known as “drugs of addiction”, though ketamine is a different beast compared to other party drugs. Cocaine, for example, is an ‘upper’, sharpening talk and energy. MDMA is an empathogen, meaning it dials up feelings of warmth and closeness (that classic, “I love everyone” glow), while cannabis is a depressant – a soft-focus filter that can dull anxiety. Ketamine, meanwhile, is a dissociative that pulls you inward, making your body feel distant from your mind, where dose and setting dictate the level of pain relief or disorientation. Heavy, chronic use can prompt ketamine-induced cystitis, and in very severe cases, users might need to have their bladders removed.

Emma hasn’t touched the drug recreationally since her K-hole experience. Ironically, she handles it often at work in the ED of a Melbourne hospital. There, ketamine comes in a 200mg vial; it’s the drug you reach for when you need to “knock someone out safely” for a short, painful procedure, such as realigning a fractured wrist or dislocated shoulder. “We use it because it doesn’t drop your blood pressure, it doesn’t drop your heart rate, and most of the time you can keep breathing on your own,” she says. Dosed carefully in small IV “pushes”, nurses watch for a “safe dissociation”, where the patient doesn’t remember the manipulation, but their airway remains open and clear of blockages.

The drug’s notoriety has expanded thanks to prominent headlines over the past few years. When the Friends actor Matthew Perry died suddenly in 2023, the County of LA Medical Examiner cited the “acute effects of ketamine”. And earlier this year, Elon Musk dragged the substance into the political arena after The New York Times reported he’d used ketamine regularly on the 2024 campaign trail, sometimes mixing it with other drugs. Musk has publicly said he takes “a small amount” by prescription for depression and has denied broader misuse.

In Australia, the number of recreational users is rising: the most recent national wastewater program reported record-high ketamine consumption, and Border Force says imports are surging. And, as always, things take a riskier turn outside a clinical setting – street ketamine can be diluted or substituted entirely. “We send a tube to toxicology when people come in unconscious,” Emma says. “People who think they’ve taken ketamine – it’s actually cut with multiple other things.”

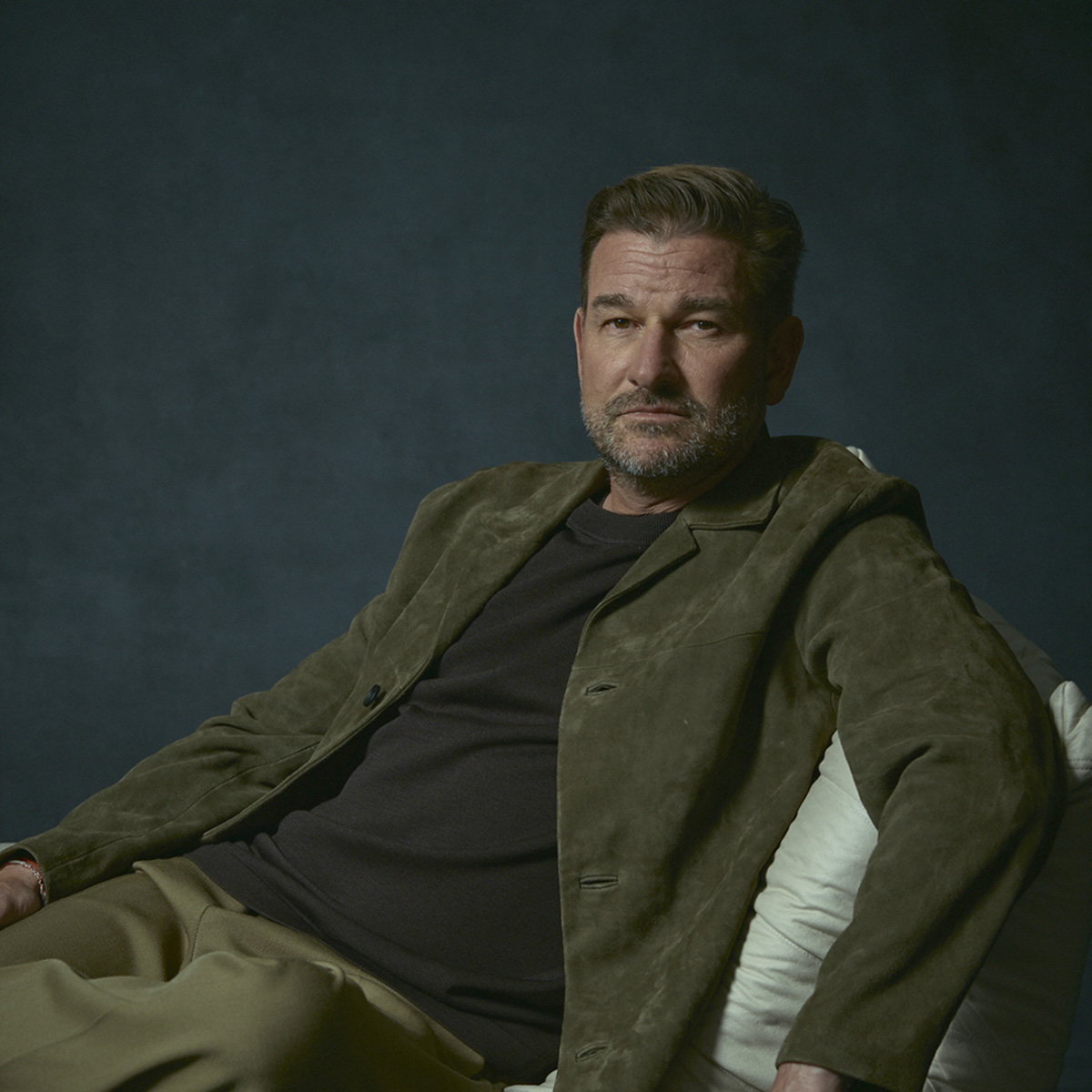

John (not his real name), a NSW-based clinical psychologist who has used ketamine recreationally in the past, describes the sensation that makes some clinicians hopeful. “It turns me very introspective,” he says, acknowledging that his ideal ketamine trip would be occur alone in a dark room with music playing. “It really equipped me with the tools to realise that, although my thoughts are real, they’re not necessarily true. We shouldn’t believe everything we think.” In therapy, John spends weeks teaching people to gain that kind of distance from their thoughts. “What therapy might take 20 sessions to teach, ketamine can sometimes do in one three-hour trip – provided it’s well supervised with a competent practitioner.”

Professor Paul Glue, a psychiatrist and researcher at the University of Otago, is still astonished by the results of initial trials published by Yale 25 years ago: “Early on [the findings were] electrifying because nothing else worked that fast,” he says. But ketamine is not a one-and-done cure, and, for many, maintenance is part of the deal. “Basically, people need one to two doses a week to keep themselves well,” he says.

Glue’s team is working on a slow-release oral ketamine tablet designed to favour the metabolites that are thought to drive mood improvement. “The tablet is like a little rock,” he says, sharing a video of what he says is a tablet of ketamine resisting pulverisation by a hammer. “You can’t crush it. If you sand it, it turns to snot when it hits water.” Glue says peak blood levels arrive hours later, not minutes, so it’s “not something that’s going to give you a buzz”. If the tablet’s trials succeed, he estimates potential approval would be a couple of years away, which could change the face of how depression care could be delivered – shifting away from boutique infusions toward a scalable, pharmacy-dispensed treatment with lower clinic burden.

The issue of street versus pharmaceutical ketamine remains crucial. The latter is sterile, single-substance, traceable and dosed by weight under supervision. The former is guesswork, but with the cost of living (and alcohol) rising, microdosing has crept into young professional circles. Emma sees it among colleagues who’d rather take intermittent “bumps” on a night out than spend $17 on a pint of beer: “They’ll just do a little bit of ketamine when they go out and they won’t drink”.

For John, any fear is anchored less in a moral panic than in missed potential. “I would want people to understand the overwhelmingly positive amount of evidence we have supporting it as a treatment for treatment-resistant depression,” he says. “We need more research . . . but this drug has the potential to save a lot of lives.”

Related:

Alex Russell’s Lurker is Misery for the social media generation