Discovering the lesser-known side of Fiji

Eschewing Fiji’s renowned resort scene, we venture into the mountains to experience a land that transcends glossy brochures and enriches the soul.

THE SUN RISES to a chorus of cockerels eager to welcome the morning. The cloud hangs low, enveloping the handful of homes that make up the remote village of Naga (pronounced Nan-Ga) high up in the mountains of Fiji’s largest island, Viti Levu. As the sun breaks the horizon, light floods the valley, illuminating the landscape, as though God himself has turned on the light.

The village springs to life in an instant. Bible scripture is bellowed through a crackly megaphone driven by the beat of a drum. A group of women bang pots and converse loudly as they finger out perfect circles of roti to break the fast. Men of varying ages survey the sky and point assuredly into the distance, discussing something of apparent importance. A trio of battle-scarred dogs lick moisture from the grass, their wounds the result of hunting wild pigs in the surrounding hills.

This is Fiji’s interior, a lush, green, mountainous landscape; one tended by communities of Indigenous Fijians for over 2,500 years. For the next few days, the valleys are my temporary home as I uncover a lesser-known side of this exotic hotspot, one less concerned with almond lattes and perfectly poached eggs and more with harvesting crops and the daily market price they fetch.

Beyond the brochures

Fiji’s tourism sector has undergone a transformation with the emergence of a small group of operators providing unique experiences beyond the family-friendly resorts and surf destinations that hug the coastline. Largely driven by small owner-operator enterprises, this new type of experience is enticing people away from poolside cocktails, white beaches and turquoise waters.

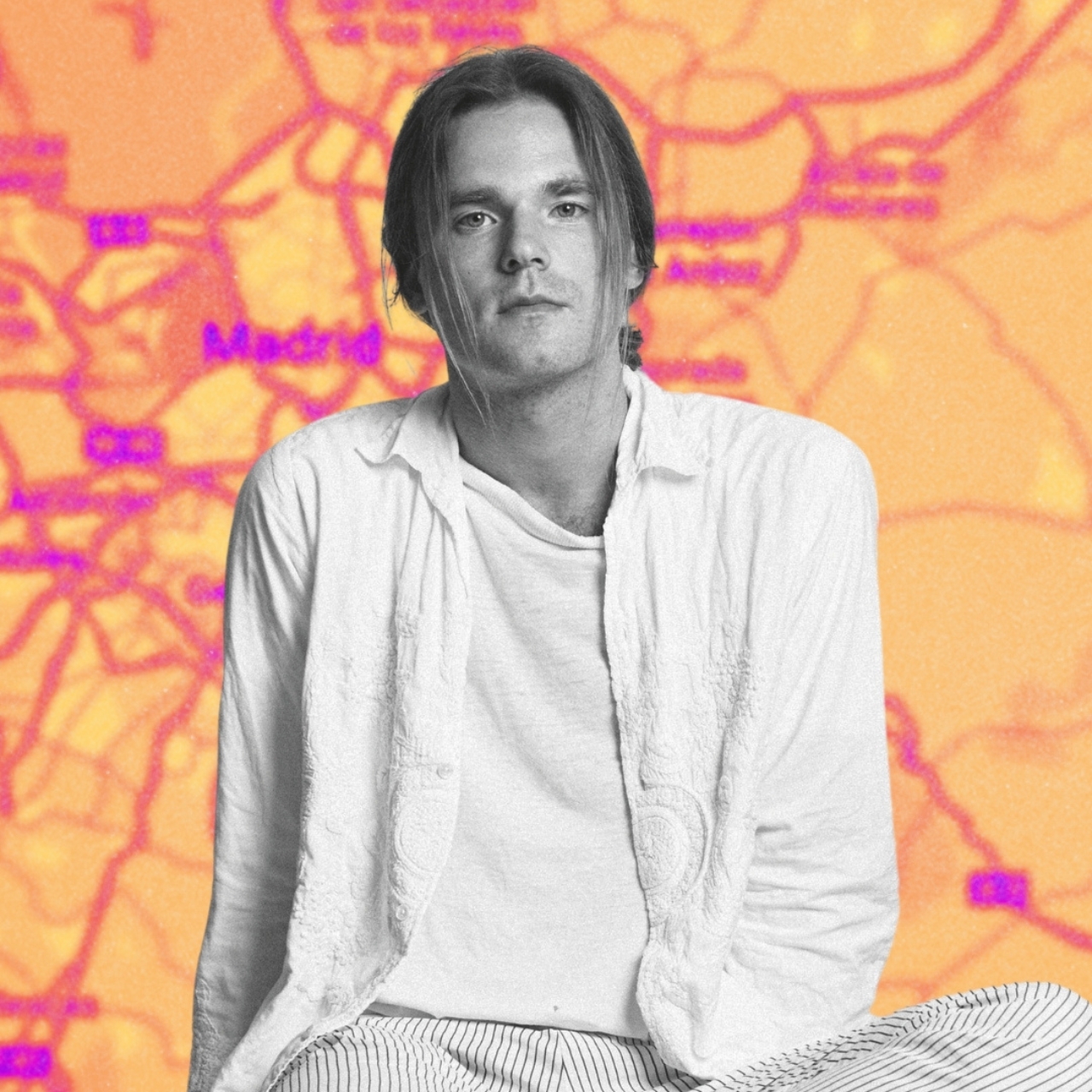

“Traditionally, tourism here has been geared towards us and them,” says Matt Capper, co-owner of Talanoa Treks, and the operator behind my hike into the Highlands. “Visitors stay in hotels, head out on day trips to a village or waterfall and then back to the hotel. We thought we could do this differently, working in partnership with communities… an alternative way of doing tourism.”

Historical and cultural attractions have always played a pivotal role in attracting travellers from across the world. Fiji’s colonial history, particularly under British rule, is unmistakable and can be seen in everything from its food to its architecture—with colonial-era buildings and forts still standing as historical landmarks. Yet, by and large most who visit only see Fiji’s fringes—within sight and sound of the ocean.

The Fijian culture itself is unique, even among other Pacific Island nations. It is deeply rooted in tradition with a strong emphasis on family and communal living, ceremonies and rituals. Over the years, the Fijian government has invested in preserving and promoting its historical heritage, which seeks to protect its stunning natural landscape but also preserve its culture amid increasing Western influence and modern infrastructure.

Having discovered Fiji’s interior through a local hiking community, Capper and his business partner Marita Manley built Talanoa by establishing a cooperative of communities to provide homestays in remote villages for travellers seeking to experience traditional life. To support the villages, the team provides minimal supplies and equipment to sustain visits a few times a month, such as mattresses and blankets, as well as training in guiding, food prep and first aid. “We just try and keep a balance,” he adds.

This focus on immersion is proving popular with travellers happy to forgo the air conditioning of the Sheraton or Marriott in favour of experiences that showcase Fijian nature and family life in a different way— promoting sustainability and equal opportunities for the people that live there. This has resulted in the creation of the sustainable tourism collective in Fiji called Duavata, a group of operators who believe ‘tourism should enhance cultural heritage and the environment’—of which Talanoa are a part.

Heart of gold

Getting into the interior of Fiji requires some preparation and a fair amount of help. Other than the sugar cane tramway used to transport raw cane to the country’s main mill, the only way through Viti Levu is a four-hour slog by 4WD, from either Nadi in the west or Suva in the east.

“Hiking through Fiji is an adventure,” says Ratu Peni Semira (or Ben for short), my guide for my three-day trek across the Sigatoka River and the border between the dry and the wet side of the island. “Guests come from all over the world,” he says, as we navigate a rather precarious pothole. “[They visit] our beautiful Highlands and experience the real Fijian culture and immerse themselves in Fijian village life to understand our way of life.”

I was welcomed to Naga with a tour of the village, a magnificent sunset, and a kava ceremony; a traditional gathering where a mildly intoxicating drink made from the root of the kava plant is shared as a symbol of friendship and welcome. Each bowl is followed by a slice of boiled cassava, or “chaser”, a snack often consumed between servings of kava. Its effects become apparent after the fifth or sixth coconut bowl, when my left leg starts to fall asleep. “With alcohol you start down and end up,” explains one of the village elders, “With kava, you start up and end down,” he laughs.

From Naga we trek up and over the hills towards the village of Nubutautau, following a narrow track worn into the land by bare feet and gum boots over many years. It’s easy to see why people are drawn to hiking in Fiji. The country offers a mix of lush rainforest and challenging, rugged terrain, pristine waterfalls, and dramatic volcanic peaks. Let’s just say your camera gets a workout.

Our guide is Naga local, Sairusi Rokomatu, (or Si for short), who tells stories and explains aspects of Fijian culture through deft swishes of his machete. While I stop to take some photos, he explains everything from what he farmed and when, to the importance of tabua, a whale-tooth gift that symbolises respect and honour, and how every person mixes their kava a little differently.

Si says hosting visitors has proven to be a positive for his community. “We share who we are and how we live with the land,” he explains, “and in return they can better support and provide for our community.”

Adds Ben: “We have made a considerable impact on the communities we work with. From capacity building in business and health and safety, to improving village infrastructure. It’s nothing fancy. It is working with their natural resources and their Indigenous lands to build a tourism model that is eco-friendly and sustainable.”

Future proofing

Jake Taoi is a conservationist with Nature Fiji, the country’s only NGO, working for the conservation and sustainable management of Fiji’s cultural heritage. He works closely with operators and communities to provide them with an alternate source of income and support to run a local tourism enterprise where the culture of the community and their surrounding landscape is the main product.

“Sustainable tourism can easily become a feel-good hashtag,” he says. “However, when applied wholeheartedly with the people, culture and environment in the centre of the initiative, the warmth of the Fijian Bula and our beautiful God-given landscape can be enjoyed for generations to come.”

Even with operators like Talanoa Treks blazing a trail for sustainable tourism in Fiji, conservation and ecotourism faces several challenges. Critics argue that increased tourist footfall can inadvertently harm fragile ecosystems and disrupt local cultures. It is thus the role of government and operators to strike a balance that can stand the test of time and both provide and preserve.

Ultimately, eco or sustainable tourism must balance access, experience, and service with the impact it has on communities and how they live. Done well, it serves as an opportunity for communities to access new revenue streams in a way that improves their lives and maintains their culture. Done poorly, and culture is eroded in favour of shops selling imported magnets, while the gentrification drives people further away, priced out by the very industry they helped to produce in the first place.

“Tourism is bringing so many people into Fiji,” says Makayla Halter, a tourism operator for Talanoa Treks. “We need to consider the future and change how we’re operating to not destroy our home island and home.”

The future of tourism in Fiji’s interior lies in responsible and sustainable practices. By prioritising environmental protection, respecting local traditions, and providing education, Fiji can ensure a harmonious coexistence of travellers and nature. This approach will not only safeguard its natural and cultural treasures but also offer enriching, authentic experiences to future generations of visitors.

Some of these experiences are hard earnt. While making the final 90-minute ascent into the village of Nubutautau, lactic acid is building in my legs, sweat pouring down my face and my camera banging into my leg like a 20kg dumbbell. At this point, it’s hard not to question my decision to abandon the tourist trail for an adventure when I could be pottering about on a paddleboard.

But as I crest the summit to the cheers of the local children, the land rolls out before me like a plush green carpet and I receive a welcome I’ve come to know as wholly Fijian. As I’m embraced by a man with a gold-speckled smile, I’m glad I swerved the comfort of the Coral Coast in favour of the warmth of the Highlands. Bula indeed.

Related:

How you can use the many benefits of meditation to master mindfulness