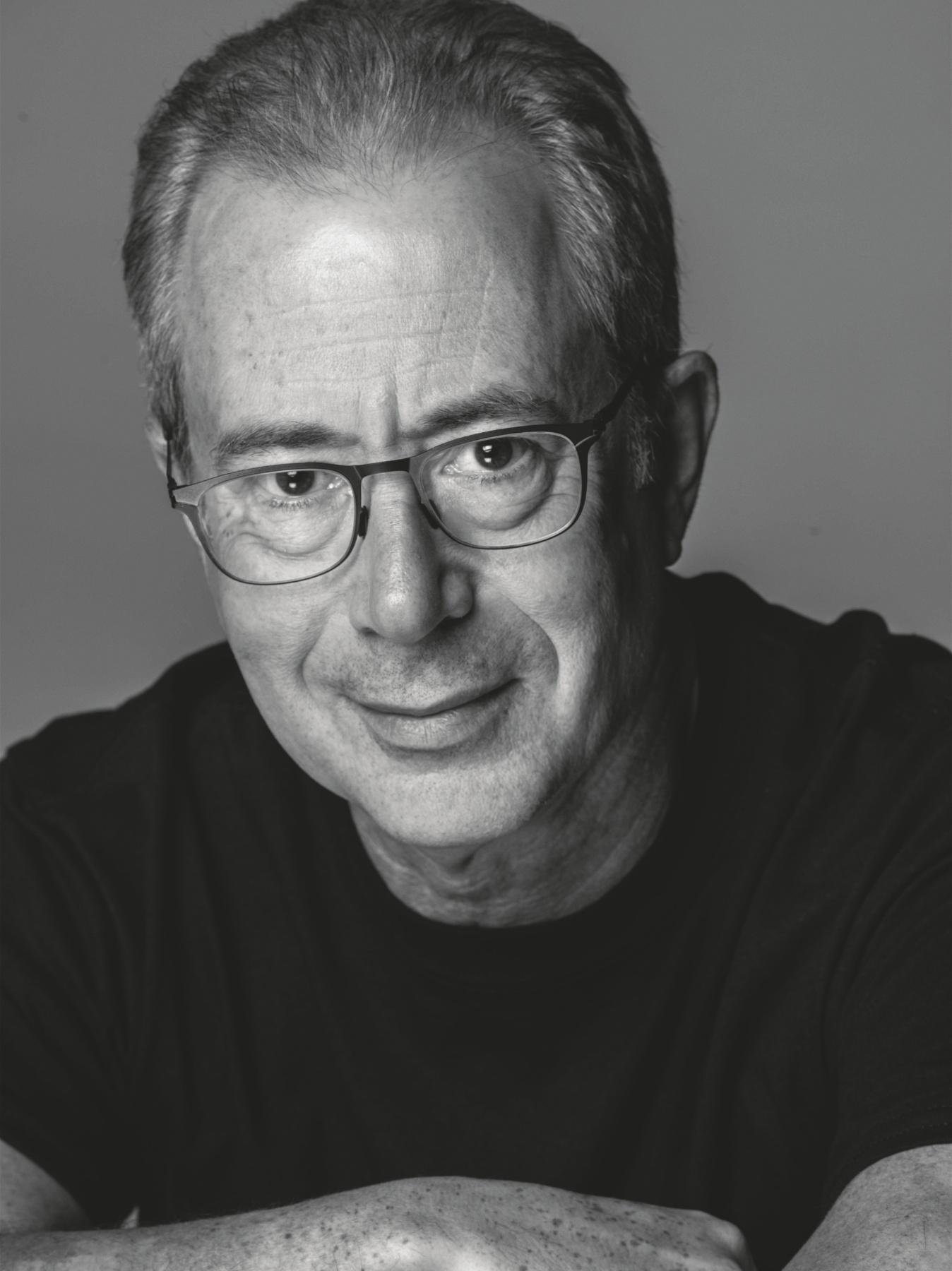

Marlon Williams on singing in te reo Māori and returning to his roots

At first, Marlon Williams was nervous to tell people he was writing an album in Māori. Five years later, and he’s playing it to audiences all over the world, each performance as cathartic as the last

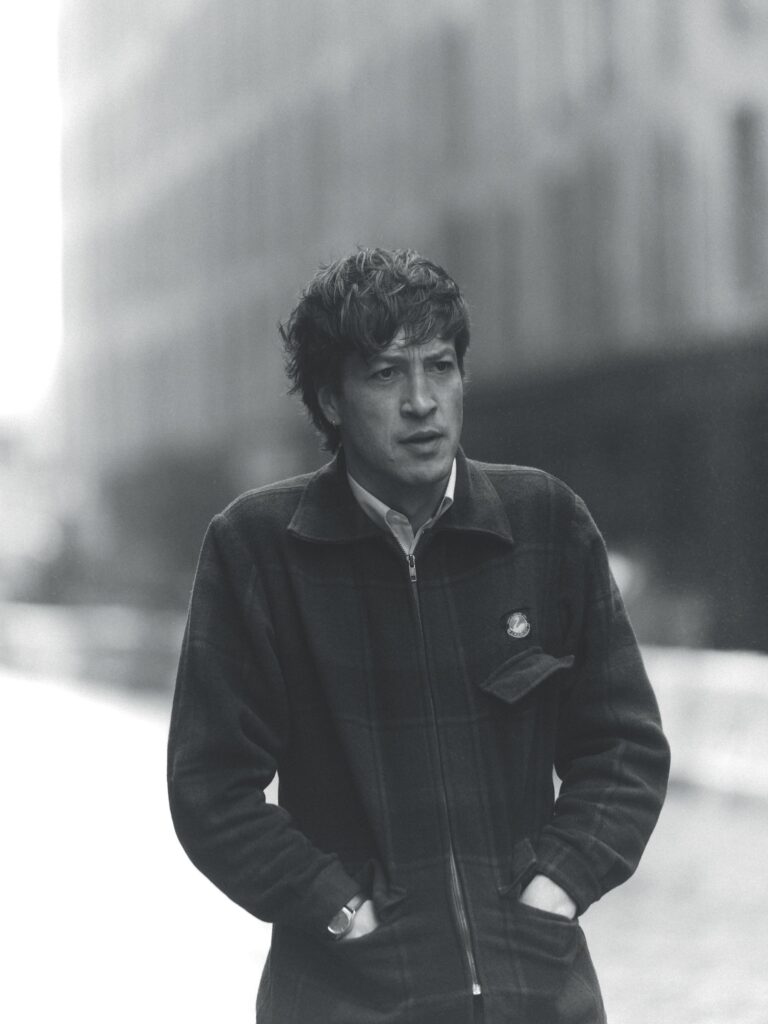

MARLON WILLIAMS IS WALKING to his car to retrieve a cigarette. “You don’t mind if I just potter around while I talk to you, do you?” he asks. “Sometimes I get a little fidgety.” The car, I realise, is the same “lil hot hatch” that features in the music video for ‘Rere Mai Ngā Rau’, a track off Williams’ new album, Te Whare Tīwekaweka, which came out in April. The video follows the musician and his buds as they hoon around his hometown of Lyttelton, not far from Christchurch on New Zealand’s South Island. He moved back here in 2020, following a decade spent living in Melbourne and touring abroad. “I love Melbourne, but I think I’m more made for the climes and the landscapes of New Zealand,” he remarks as he lights up. Lyttelton – or Ōhinehou as it’s known in Māori – is a historic port town with a sparkling bay that doubles as the local swimming pool during summer. People greet one another with a hearty ‘Kia Ora!’ in the streets. It’s not difficult to see why he likes it here.

Te Whare Tīwekaweka is the first album Williams has written entirely in te reo Māori. It also marks the longest he’s spent working on a body of music – he wrote the debut single, ‘Aua Atu Rā’ (English translation: ‘Thank you Very Much’) in 2019, but put it to the side when he moved back to New Zealand, instead commencing work on what became his third studio album, My Boy. But My Boy didn’t come pouring out of Williams in the same way his self-titled debut and critically acclaimed follow-up, Make Way For Love, did. “It wasn’t an overly easy record for me to write. I was just running up against all of these creative walls,” he says.

After releasing My Boy and touring it around the world, he decided to return to ‘Aua Atu Rā’. Tinkering with lyrics in his ancestral tongue, rolling the different vowel sounds and language devices around in his mind, led to something of a breakthrough.

“When I turned back to the Māori, the walls weren’t coming up in the same way. I wasn’t getting stuck in the same cul-de-sacs because I had the novelty of new tools to use,” he reflects. “English is everywhere. I’ve been writing in it my whole life. But some of my earliest, most formative musical experiences are in Māori. So, it feels, in some sense, very natural to be doing it. But . . . there’s also some fear around not being a fluent speaker. For a lot of Māori who don’t have it as a first language – and I imagine this is universal to a lot of people from cultures with endangered languages around the globe – there’s this really physiological sense of shame that comes rushing in as soon as you think about, Well, why shouldn’t I be able to speak Maori?”

Williams is Māori on both sides of his family – his mother’s tribe, Ngāi Tahu, is from the South Island, while his father’s, Ngāi Tai, is from the North. He grew up speaking household Māori at home – “really basic things like ‘wash your hands’,” he explains – and travelled annually to tribal meetings with his mother, cram-learning songs on the car trip so they could participate in the singing. But primary school and high school saw his grasp on the language loosen; those classes clashed with music on his timetable, and by then, he’d decided he wanted to become a singer.

“I’ve never pulled it fully into focus, in a way where I’ve been able to become deeply conversational,” he says of the language. “So I think, when I started writing the album, I just felt a bit sheepish. Like someone was gonna laugh at me, or be like, ‘Well, you write such great songs in English. Don’t try and start a new thing when you don’t know what you’re doing.’”

He chuckles, but he’s not joking.

“One of the darkest parts about the marginalisation of a culture is that once it becomes marginalised, there’s less access to the culture and to the language and therefore less room to move once you’re in that space, because there’s a real sense of responsibility in terms of the signal you’re putting out to the rest of the world about what the culture is,” he says. “So, it’s this constant tension between preservation and innovation, where you’re trying to heed this thing that’s so crucial to art – which is knowing the rules, and then breaking them. But if you don’t fully know the rules, then breaking them is a fraught game. And I know I’m breaking some rules without full knowledge of what the rules are, which. . . it’s scary in some sense.”

IN THE CAREER ARC of Marlon Williams, now is an interesting time to be releasing an album that most of the world – and his fans – can’t understand. Since putting out Make Way for Love in 2018, Williams has enjoyed immense international success. He’s toured with Florence & the Machine (the duo performed an unforgettable rendition of Williams’ tear jerker ‘Nobody Gets What They Want Anymore’ at the British singer’s Sydney arena show in 2019) as well as with compatriot Lorde (during her 2022 show at the Roundhouse in London, where they performed a duet of ‘Stoned at the Nail Salon’ in Māori, the ‘What Was That’ singer referred to Williams as “the great heartthrob of New Zealand right now”). He also landed a scene-stealing cameo in Bradley Cooper’s 2018 directorial debut, A Star is Born, among other acting projects, including a role in the Netflix original series Sweet Tooth.

You see, Williams isn’t just New Zealand famous – with his 6’3” frame, soft mullet and dangly earring, the 34-year-old gets recognised all over the world. In addition to looking like a rock star, a big part of his popularity boils down to the way people connect to his lyrics. The break-up he chronicles on Make Way For Love? We’ve all felt the depths of that malaise. The examination of masculinity that’s threaded throughout My Boy? Also relatable. So, at a time when he could’ve waded into the poppier waters his previous releases lay the groundwork for, why choose now as the time to write an album that only a small percentage of his fans can comprehend?

He thinks for a moment. “I’ve spent a long time touring around the world, and I guess when I moved back here, that brought a few things to the fore for me. It made me feel like, Why have I left it for so long to do? rather than, Why now and not later?

“I’ve always loved listening to music I don’t understand,” adds Williams as he butts out his cigarette. “I think people can get a little too caught up with the literality of lyrics. We listen to the lyrics and forget how our bodies are reacting to the music. I think the journey of first hearing a piece of music that you don’t understand, and letting that wash over you from a place of having distance from the literality of it – that is a form of poetry in itself.”

Te Whare Tīwekaweka also arrives at a moment when Indigenous language projects from First Nations musicians all over the world are receiving unprecedented popular acclaim. Yolŋu rapper Baker Boy has been recording in his native language for years; Puerto Rican artist Bad Bunny, who sings predominantly in Spanish, is currently one of the most-streamed artists in the world; the Irish hip-hop trio

Kneecap, who swept through Australia on a sold-out tour earlier this year, switch between rapping in English and Gaeilge – plenty of their lyrics go straight over the heads of fans, but no one is disputing that their songs are total bangers. It’s a powerful notion: by introducing languages at risk of extinction to a new generation through music, these artists are helping to keep them alive.

“Without meaning to belittle it all, I think Indigeneity is kind of hot right now,” says Williams with a wink. “I’m saying that in a silly way, but I do think it’s a really positive thing – that people are allowing themselves room to come to the music.”

Lorde, who also released an abridged version of her 2021 album Solar Power in Māori, features on Te Whare Tīwekaweka, her ethereal vocals harmonising with Williams’ croon on the track ‘Kāhore He Manu E’. But the album’s most crucial collaborator is Williams’ dear friend, a Lyttleton-based rapper who goes simply by Kommi. “They are something of a shapeshifter, Kommi,” laughs Williams. “We met at a party in 2017, or 2018, and got into this drunken yarn about the Māori worldview, but through a German phenomenological lens.” When writing the album, Kommi, who is fluent in te reo Māori, became Williams’ sounding board, educator, editor and emotional support. “I had a bucketload of whakamā [self-doubt] to push through before I could even approach Kommi about helping me write songs in Māori,” acknowledges the singer. “But he helped me to believe that I could find interesting things to say using the language as a lens.”

WHILE THE ALBUM dropped in April, a documentary film on the making of Te Whare Tīwekaweka will receive its Australian premiere at the Sydney Film Festival in June. Directed by award-winning Kiwi filmmaker Ursula Grace Williams, Marlon Williams: Ngā Ao E Rua – Two Worlds threads together footage of Williams’ life on tour – thrilling one minute, lonely the next – and scenes of him back home with friends and family that are tinted with a dreamy sepia tone reminiscent of a Wes Anderson film. The Williams you see on screen is the Williams you get in person: he’s witty and thoughtful, speaking in metaphors only someone who was born to make music could conjure.

At one point in our conversation, on the topic of Māori love songs and the difference in the way language is used to describe emotions, he offers up the following observation: “Every love song feels like a room, and you’re moving around the different rooms of this emotional house, where you can go and sit for a bit and be like, ‘This is what this emotion is doing to me’.

“With every record, you hope that you’re rediscovering music again,” he continues. “You’re discovering as you make the thing, and then at some point, when you’re finished with it – it’s a bit like a relationship. You’ve decided there’s an end date to it, and you have to make the break from what was.

“But I’ve definitely gone through that with this album. Music was all of a sudden this fresh, alive thing again. It also feels exciting, in terms of what’s possible for the future now. I’ve got ideas of making a Māori country album that’s like a classic honky-tonk album. And maybe it’s not even fully in Māori; maybe it’s just dipping in and out.” He smiles. “Who knows?”

After touring the album around North America and Europe – he sold out three shows in London, as well as his New York and LA shows – Williams will make his long-awaited return to Australia and New Zealand. Following a show at the Sydney Opera House as part of Vivid Live – his first time playing the main concert hall – he’ll cross the Tasman to play Te Whare Tīwekaweka to those for whom it holds the greatest significance.

“I love playing out a record and seeing how it lands in different rooms,” he says of hitting the road with a new, and very different, body of work. “You learn a lot about the songs. You know, once the chemical is exposed to oxygen, it takes on really different qualities.” Until then, he’s soaking up the sepia hue of Lyttelton. “I’m going to go play some basketball,” he says of how he’ll be spending the rest of his afternoon. “Yeah, that’s what I’m gonna do.”

Marlon Williams performs at the Sydney Opera House on May 29 during Vivid. Tickets are available here.

Related: