On a run with Bill Shorten, I learned there was more to the former Labor leader than stilted zingers

With the former Labor leader announcing his retirement from politics, Esquire columnist Ben Jhoty recalls how a jog around Sydney with ‘Bill’ revealed a side of the man at odds with his public persona

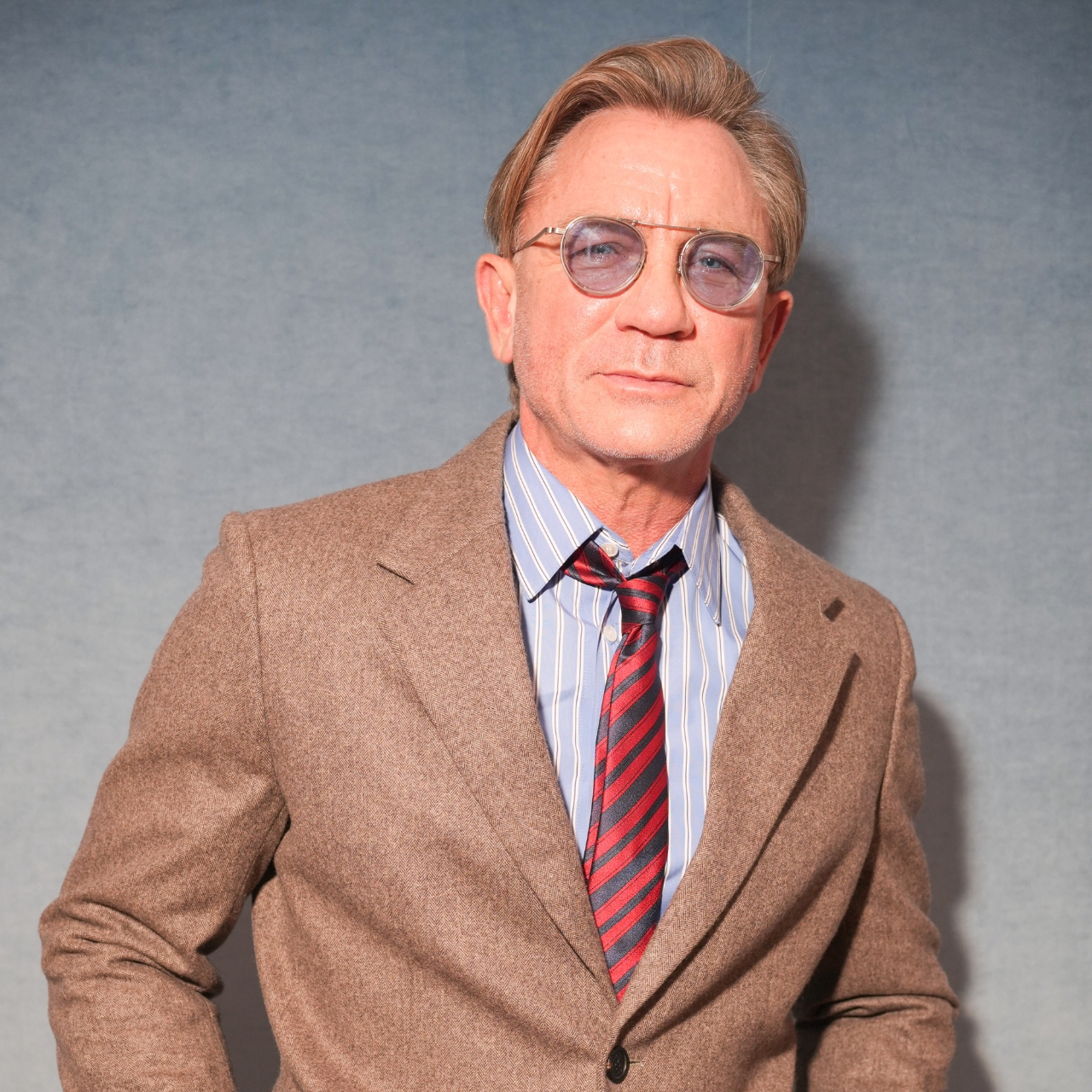

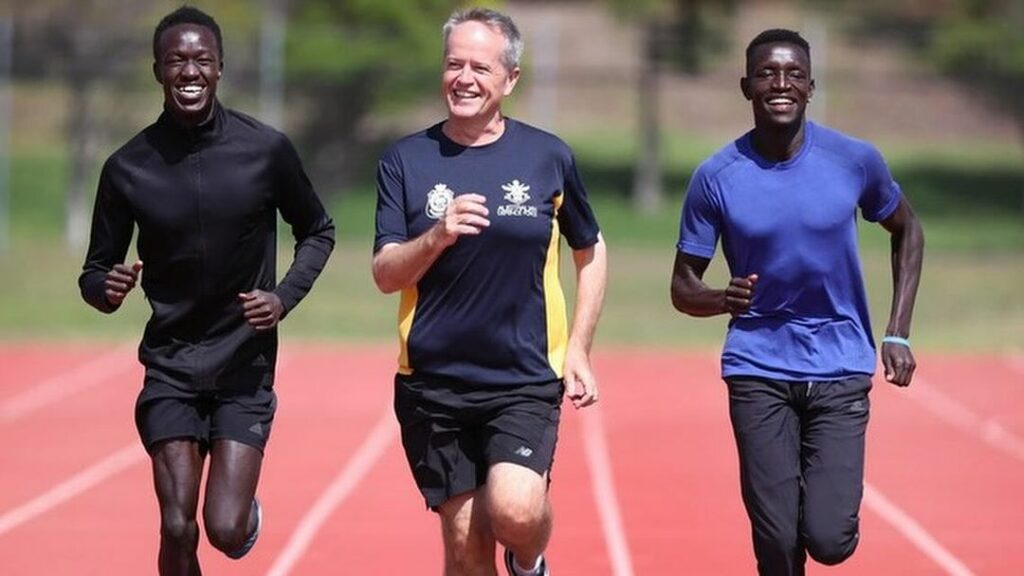

BACK IN 2017, then opposition leader Bill Shorten was running – in more ways than one. The former Labor leader was preparing to run for office in an election that eventually arrived in 2019. He was also running on his own two legs, having embarked on a year-long regimen that had seen him pounding the pavement daily across the country, as part of a broader strategy to get ‘fit for office’. He was also running and conducting interviews quite a bit with the media, presumably to spread the word about how much he was running.

When his press secretary reached out to me, I eagerly took up the invitation to go for a jog around Sydney with Bill. Yes, we’re on first name basis after our 45-minute trot together.

I remember feeling both nervous and curious as I fronted up to the Hilton Hotel on George Street, where Bill was waiting with a few plain-clothed security goons and some political lackeys. They would be accompanying us but, I was assured, would keep their distance so Bill and I could chat, man to man.

I knew Bill mostly from his appearances on the ABC’s Q+A, where I thought him to be an engaging and persuasive bloke. But I was also aware that he was seen as a ruthless numbers man behind the scenes, having orchestrated the ousting of Kevin Rudd as PM in 2010. This was distinct from his wider public persona, which often saw him acting awkwardly and stilted at press conferences, reeling off a succession of ‘zingers’ as he tried, too hard perhaps, to connect with the Australian public.

So, I was anxious to see which version of Bill I’d be running with and, just quietly, how good a runner he’d be – as the then deputy editor of Men’s Health Australia, I did not want to be dusted by a dorky politician, after all.

Bill’s initial handshake ticked all the boxes for a politician meeting a civilian: firm grip, strong eye contact, a toothy smile, followed by a completely unnecessary, “G’day I’m Bill”.

We set off and it became immediately clear I needn’t have worried about Bill showing me a clean set of heels. The former trade unionist ran at what I would generously term a leisurely pace. He asked if I had kids, which I assumed was a default conversational gambit aimed at establishing common ground. Unfortunately, at the time I did not, leading to an awkward silence. Bill broke it by asking about our magazine’s Facebook subscribers – always a numbers man – possibly doing some calculations in his head. This isn’t going great, I thought.

It was when we reached the first set of traffic lights that the mask slipped. As we waited for the green man, I anxiously pounded the button, to which Bill drily observed, “I find the more you hit those buttons, the quicker the lights change”. I looked at him a little blankly, before detecting the hint of a smirk cutting the corners of his mouth. Bill Shorten was taking the piss out of me.

From that moment on, I felt at ease in his company. Bill was a smart-ass, I realised, which allowed me to loosen up and offer a few subtle jibes of my own: “Is this your regular pace, Bill?”

As we ran around Observatory Hill to the Opera House, we began to talk easily about running, about sport, work, travel – I believe I made a joke about John Howard’s bowling action. If it hadn’t been for the lingering presence of the goons and lackeys, I could have been running with any other suburban dad in the country. What’s more, I realised I was enjoying Bill’s company.

Continuing around Mrs Macquarie’s Chair, I carefully observed how people on the street were reacting to us. The odd person waved, some looked twice and there were a few “Hi Bill’s”. I asked him if he ever encountered any abuse out on these runs. Bill said it occasionally happened but was pretty rare. “Most people are pretty genuine, I find, don’t you?”

I agreed that I did, but have wondered, on reflection, if Bill wasn’t being a little bit disingenuous himself, on that point. Whenever someone said ‘Hi’, Bill’s face lit up, the mask reassembled itself, and he uttered, what I observed to be eager but awkward, ‘Hellos’ back. Personally, I preferred the smart-ass Bill.

We all put on masks at work and politicians who are in the public eye are required to go full fancy dress – Paul Keating once said of campaigning that “every now and then you have to flick the switch to vaudeville”. Campaigning is about appearing as the quintessential everyman – who can forget Scott Morrison’s baseball caps, Tony Abbot’s bike rides (and onion chomping), or John Howard’s green and gold-track suited morning walks. To be successful at it, you must be able to kiss babies, perform silly dances on breakfast TV and don hard hats and hi-vis while visiting a manufacturing plant, without being unduly troubled by self-consciousness, irony or the absurdity of the situation. This requires a certain type of personality to pull off. In my 45 mins with Bill, I felt that it was probably not his strongest suit, something that was perhaps borne out by his 2019 election loss to Scott Morrison.

In many ways, I respect Bill’s inability to play the fool, which ironically, made him more relatable to me. I was also interested to see the generous comments from former parliamentary foes upon news of Bill’s retirement yesterday. Bill, who’s still only 57 and married to wife Chloe, with whom he has a daughter, as well as two other children from Chloe’s previous marriage, will become the new vice chancellor of the University of Canberra. I nearly dropped my washing basket upon hearing this news for ‘UC’ is my alma mater – if only we’d known back then where you’d end up, Bill! It could have got us through that awkward two minutes on Philip Street . . . enjoy the chips and gravy in the uni refectory!

Opposition Leader Peter Dutton described Bill as a “decent person” while the man who beat Bill in the 2019 election, Scott Morrison, said: “Congratulations on your service to Australia and your party. There is life on the other side. It’s a precious time ahead for you, enjoy it together.”

Now this kind of generosity is relatively common upon an adversary’s retirement, as politicians finally lay down the proverbial shivs and shanks they’ve been attacking each other with for years in parliament and the press. There are usually bon-mots about public service and making a difference. Much of it is likely performative, in and of itself, but it is perhaps also revealing of the real and genuine relationships that exist between politicians of different stripes behind closed doors, where they can be themselves.

Kevin Rudd was famously chummy with Julie Bishop. More recently, NSW premier Chris Minns and former premier Dominic Perrottet shared a warm relationship. Similarly, Minns has gone out of his way to pay tribute to the role his political opponents – Gladys Berejiklian, Mike Baird and Perrottet – played in construction of the new Sydney Metro line. I found the sentiment somewhat heartwarming and judging by the comments sections in various articles, so did a lot of people; it showed politicians to be human beings.

Of course, there are undoubtedly a lot of strengths in having a robust democracy and an adversarial political system. But it is perhaps a pity that once a politician enters parliament and particularly when he or she addresses the public, they are forced, or feel obliged, to perform a role. To adopt an antagonistic posture in the pantomime that is Question Time and play political dress-ups as cheesy every men and women on the campaign trail. We, the electorate, will likely never know who these people really are, only the caricatured facsimile of a person who exists in the public eye.

As I discovered, behind every Bill Shorten, there’s probably a Bill.

Related: