EVERY AUSTRALIAN KNOWS WHO SAM KERR IS. Even people who, before the 2023 Women’s World Cup, had never watched a football match in their life, now know who Sam Kerr is. Something happened this year; something changed. The Sydney Opera House was illuminated in green and gold. Passengers on incoming international flights were informed about the temperature on the ground—then given the latest news on the Matildas as a chaser. “GO MATILDAS” replaced standard messages on train-station screens. It was a change that Kerr, captain of the Matildas, felt while she was out there on the pitch; she could hear it in the roar of the crowd.

“The girls and I were laughing because you could tell that the longer the World Cup went on, the more the Australian public actually understood the rules of football rather than just cheering for the team because they love us,” she says, grinning. “We would do a bad pass and they’d get angry at us, or when it was offside, they’d be screaming—it was a nice experience to see the country change like that during a month of football.”

The allegiance of the home crowd was most keenly felt in Brisbane on the night of August 12 when Australia and France played their quarter-final, which came down to an epic penalty shootout. Each time a French player approached the ball, they were roundly booed. When it was the Matildas’ turn, the reverent silence in the stadium was electric. The Matildas won the shootout, 7-6, and the crowd erupted: the home side had qualified for a World Cup semi-final. The cheers could be heard in the streets, in the house next door, on the bus. Millions watched around the world.

If you’ve been paying attention, you might’ve seen this coming—Kerr and Mewis have not been coy about their relationship. Kerr says she feels no pressure living her life in the spotlight like this, and if anything, they seem to relish it: they’re shouting to the world that they’re in love and don’t care what anyone thinks. This purity of joy has chimed with the queer community. In 2021, photos were posted on Twitter of Mewis comforting Kerr on the pitch in Tokyo after the USA beat Australia in the Olympics bronze-medal match. One user responded—perhaps innocently oblivious: “Friendship has no boundaries! Win or lose, friends are still friends.” In a deadpan reply someone responded: “They’re lesbians Stacey”. This tweet is now a viral meme; couples use it as a caption under their own relationship announcements—you can even buy it on a T-shirt that benefits a queer charity.

Kerr and Mewis find this hilarious. That game, though, was hard. “That one really sucked because it was such a shit time for me, and such an amazing time for Kristie,” says Kerr. She was emotionally torn. They both were. “It’s so hard to want someone to lose when you love them so much.”

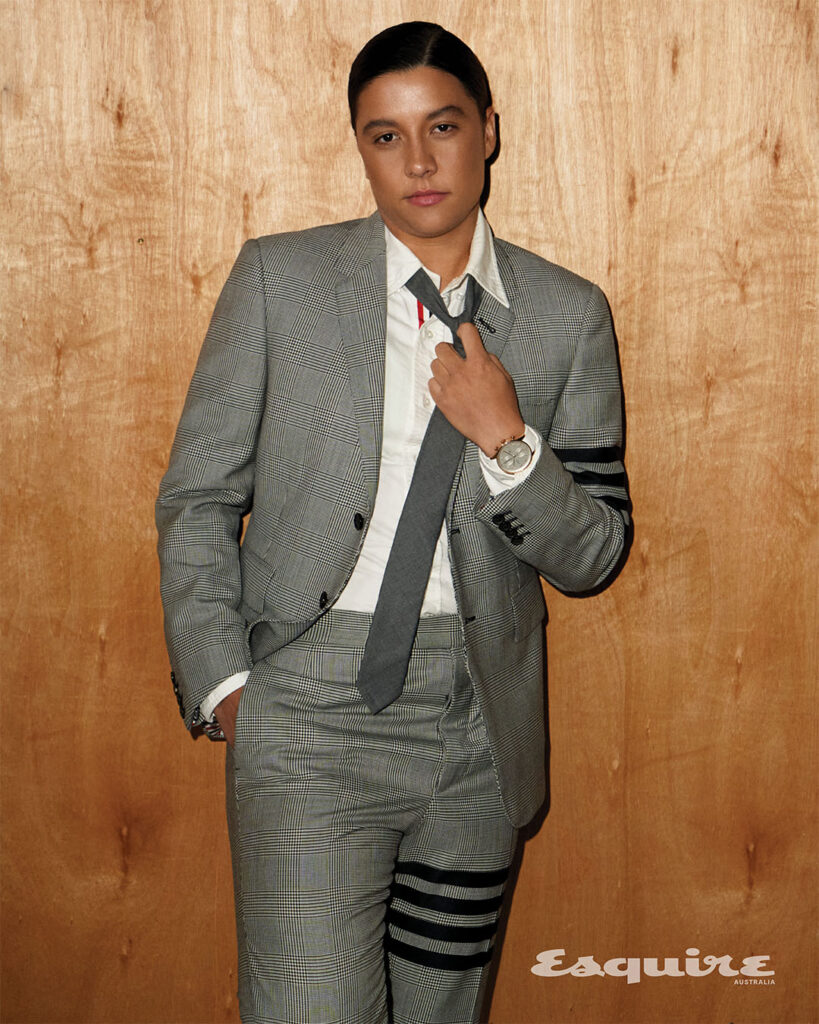

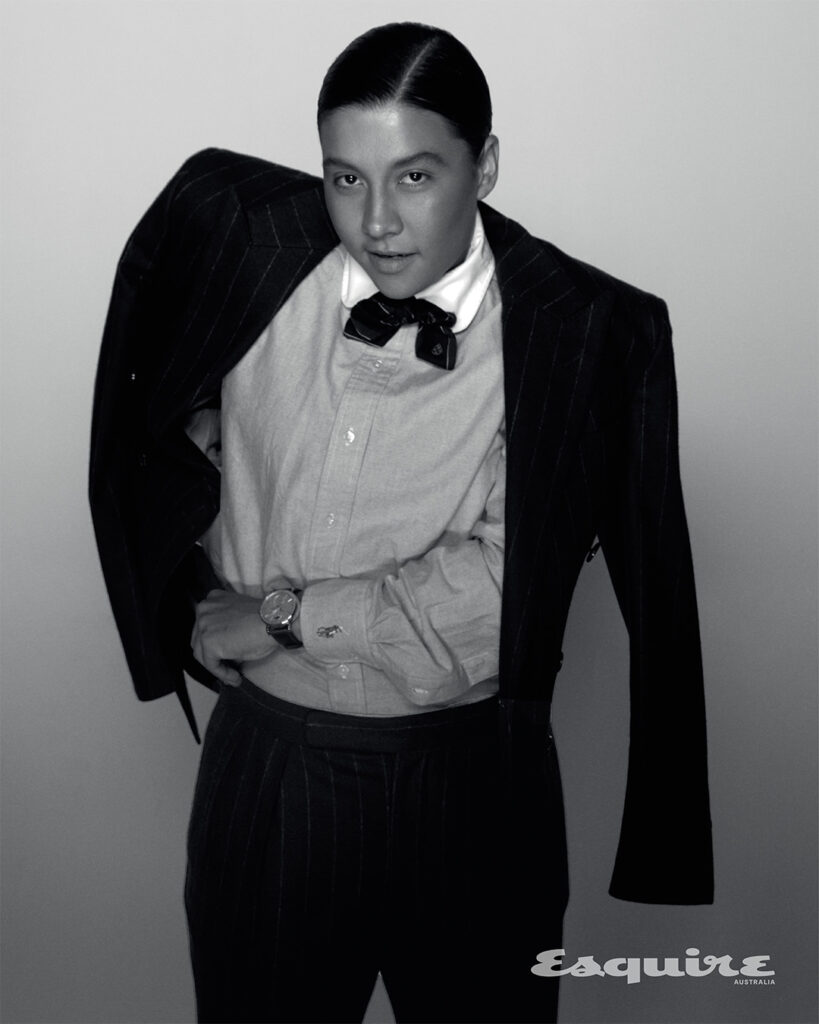

Mewis is here today, too. Kerr sits in a brightly lit chair being shown potential outfits while the make-up artist works away. In between, the couple discusses potential apartments in London for the two of them, Mewis swiping through listings on her iPad. There are questions about parking, bathrooms. It’s a small warm fire of domestic normality in the middle of a frenzy of fashion and fame.

Outside, Mewis is chipper, serving as Kerr’s photoshoot hype woman. Her new engagement ring sparkles in the fading autumn light. Burna Boy (Kerr’s choice) blasts out of someone’s phone. Mewis is pulling faces at Kerr as the latter poses for photos near a clump of bamboo, making her fiancèe smile. Would Kerr do the same for her? “She’d probably say, ‘Do I have to come?’” Mewis laughs. It’s cold, and Mewis is out here in a cropped sweatshirt. A set runner hands her a hot-water bottle. Within moments, Mewis has passed it to a shivering Kerr. “I’m from Boston,” she jokes. “We’re made of different stuff.” But she’s clearly cold—she just wants Kerr to be warm more than she wants to be warm herself.

All of this—the fame, the photo shoot, the spotlight on her private life—is a far cry from the very normal Australian childhood Kerr had back in Perth. “The only memories I have of being a kid are of sports,” she says. “I was always playing cricket in the backyard with the neighbours—[sport] has been the centrepoint of my family and my life for as long as I can remember.” She had posters of Cathy Freeman on her wall, and First Nations Australian Football League (AFL) player Ashley Sampi. She particularly liked Sampi for his ‘speccies’—where a player jumps onto someone’s back to take a highlights-reel mark. “He was always one of my idols because I used to love doing crazy stuff like that,” she says.

Kerr played netball and took part in Little Athletics, but Australian Rules and soccer (football) were the main two sports until football won out of necessity. Back then, there were no female Australian Rules teams, so she played with the boys. Eventually, it got too rough. “When you’re eight or nine years old at the start of the season, you can keep up with them. And then they hit puberty and you’re like, Oh gosh, I’m getting smashed here. I got to like 11 [or] 12 and some of the boys started towering over me and my dad said, ‘You’ve got to go’.” Kerr, who is 168cm now, was devastated. “The boys that I played with were amazing. I still run into them all the time. But the boys on the other teams didn’t know I was a girl because I looked like a little boy. To be fair, I liked that. I didn’t want them to treat me any differently. There were a few tears once they found out,” she chuckles.

Football, though, didn’t have the same level of popularity in Australia as Aussie Rules—even Kerr didn’t love it at first. This is the change she felt out there on the pitch during the Women’s World Cup, and something she wants to rectify for kids in Australia today and in the future. “I want to keep driving [attention towards] the disparity in investment from the government [in football] compared to Aussie Rules or rugby league,” she says. “For such a small country, in comparison to other footballing nations, we do really, really well. The fact that we had the Socceroos and the Matildas both qualify for the World Cup is an unbelievable achievement. The government should get behind us.”

To be fair, the Australian government put $88 million into hosting the Women’s World Cup but Kerr thinks it can go further—that it shouldn’t think in terms of a one-off investment. Her team’s success and burgeoning popularity have spawned a level of interest in football among young players that will quickly outgrow the available infrastructure.

“I’ve always felt that being an athlete is so much more than just being out there on the pitch,” she says. “I think it’s important to have role models, especially female role models, because when I was growing up, I didn’t have all the female role models that kids nowadays have.” For Kerr, these notions of example and inspiration go beyond gender. She’s proud of her Indian heritage, and often receives messages from young girls in Asia who desperately want to be professional footballers but feel they have no path to making that happen. These messages, Kerr says, “show the impact football can have not only on young girls, but on countries, culturally.”

Beyond mere visibility, she wants to be an agent of change. In Australia in 2024, she’ll be opening a nationwide school for young players—girls and boys aged 3-14—who’ll be trained, in an age-appropriate way, like professionals. It’s called Sam Kerr Football, or SKF. The logo is a simple outline drawing of Kerr backflipping over the letters. “It’s a really cool way for me to give back to the fans,” she says. “They can have things that, when I was a kid, I wish I had access to.”

ASK KERR IF FOOTBALL IS HER WHOLE LIFE and she’ll snort. “Football is a big part of my life, but it’s definitely not my whole life,” she says. “It’s my job. People think that I come home from my game and sit there and think about it and talk about it. That is definitely not the case.” When she gets home from this photoshoot later tonight, she’ll do one of her favourite things: watch a true-crime documentary encompassing the worst things humans are capable of doing to one another.

“Everyone always says I’m crazy because I go home and watch murder shows and kidnapping shows and all these documentaries on these terrible things that have happened in the world,” she says. “But I just find it really interesting how people can be so disgusting and clever at the same time.”

Sometimes she will talk about football, but she picks her moments and topics carefully. Part of the reason that she and Mewis work so well is they instinctively know when to talk about football and when not to—and when they do, they each have someone who understands not only the intricacies of the game but also the life and schedule of the elite player. In November, after Mewis’ team, Gotham FC, won the NWSL Championship in San Diego—their first title since 2009—Kerr didn’t hear from her for a few days. “In other relationships, that might be a bit of an issue. But I knew that she would be out enjoying their time, and I know that winning championships doesn’t come around very often.”

Winning is Kerr’s biggest driver. The symbols of her sporting achievements would make any trophy shelf buckle, and she’s considered one of the best strikers in the world. She is Australia’s all-time leading goalscorer and has won the Golden Boot—the award presented to the leading goalscorer in league matches from the top division of a European national league—on three separate continents. She was named Young Australian of the Year in 2018, and in the Australia Day Honours in 2022, she was awarded an OAM for services to football. There are still things she wants to win—big international tournaments, be it the World Cup or the Olympics. She also wants to help Chelsea win the Champions League. And on a personal level, she’d like to be the first Australian to claim the Ballon d’Or, football’s most prestigious individual award.

But a life like this is extremely demanding: with her training, travel and matches, there’ve been times when she’s wished for a normal life. “Me and the girls sometimes say, ‘Wouldn’t it be nice to work nine-to-five some days and just end on a Friday and go to the pub with your mates and not come back to work until Monday?’” She says this like other people talk about one day winning Lotto. “When Friday hits in my land, it’s the most intense part of the week. Whereas I see my friends going to Rottnest Island in Perth, going out on boats, doing fun things.” But she doesn’t sound sad; she sounds like she knows exactly what she’s sacrificing—and why.

“This [life] is something that I’ve always dreamed about,” she says. “And,” she realises, “it’s not forever.” Footballers, like most athletes, are very conscious of time. Careers are short. Her generation is even more aware of this: the pandemic stole two years from careers that may not last 10. Or five. “In sport, most people get the break at the end of their careers. And it’s maybe something that a lot of people, once they’re retired, wish they could go back into. So I’m trying to enjoy it while I can.”

ASK ANY AUSTRALIAN IN ENGLAND how they feel in December and they’ll say “homesick”. This is when the sun rises too late and sets too soon, if you see it at all. The difference between the UK and Australia becomes more obvious as Christmas jumpers come out, while back home—a land that feels far away and unreachable—just about everyone, it can seem, is at the beach. The longing can be felt more deeply by someone who’s lived through it before. The second or third winters in London are harder than the first, which comes as a shock and a novelty. Ahead of subsequent ones, you brace. The most regular thing about Kerr is that she’s just another Australian in an increasingly dark and cold London, missing home. “[During the World Cup] all the English girls who went out there were like, ‘Everyone is so nice, Sam! And happy! It’s not just you!’ I was like, ‘Yeah, that’s what the sun does to you.’”

It’s not only the weather. “I’m a big family person,” she says. “One part of being a footballer that lots of people don’t see is all the things you miss out on.” Missing things is what worries her most—not goals, but life moments. The mundane, the heartbreaking, the myriad occurrences that come with being a family. Her nan is growing old. Her dog, a boxer called Billie, is nine now, and Kerr has been away for nearly all of those years, living in some of the greatest cities in the world: Sydney, New York, Chicago and now London.

“I always say to the girls who play for England [that] they don’t know how lucky they are that when we get a day or two off, they can just jump in a car and drive three hours to go and see their family.” For Kerr, it would be 24 hours’ plane travel, and a massive hit of jetlag. Instead, she uses FaceTime to talk to her nieces and nephews every day. “I think, for me, that’s always something that I’ve felt a bit guilty about in my career—the amount of years I’ve spent away from home. I’ve missed birthdays. I’ve missed funerals. I’ve missed so many things I can never get back. It feels like a very selfish career path—but everyone in my family wants me to do this life.”

Christmas is a time of cultural exchange between Kerr and Mewis. Last year, they were in Perth with Kerr’s family. This year, Kerr is spending it, for the first time, in Boston. “It’s going to be different for me. I’ll probably be shivering. But it’s going to be nice to see her world and how they do Christmas—they’re probably going to be drinking hot chocolates whereas at ours, we were eating fresh seafood and drinking beers.” Mewis recalls the culture shock of Christmas in Perth as mostly “sweating in a tank top on the beach”. But she was too old to experience the thing every Aussie kid remembers: heading to the local mall to sit on Santa’s damp knees. “Santa was always sweating in that suit!” laughs Kerr.

For the next month, it’s business as usual at Chelsea. Tomorrow morning, Kerr will be training. A few days after we speak, she’ll score a hat-trick against Paris FC in Chelsea’s 4-1 win. Then, in 2024, the Olympics: the next six months will be just as intense as the last.

The life of Sam Kerr is currently one of patience and scheduling, with very little time to think about the future beyond the next game, or the next time she’ll get to see the people she loves. She doesn’t even know what she wants to do when her football career ends—except for this: “I always say that after I finish I’m literally gonna go and sit on a beach for like six weeks. Everyone’s like, ‘Won’t you get bored?!’ I’m like, ‘No way’. I’m gonna go sit on the beach and turn my phone off for a while.”

For now, though, the beach will have to wait.

Photography: James Anastasi

Styling: Way Perry

Hair and make-up: Terri Capon

Photography assistants: Stefane Belewicz and Heather Lawrence

DOP: Toby Weston

Producer: Stephanie Lawley.

This story appears in the December/January 2023/2024 issue of Esquire Australia, on newsstands December 14. Subscribe here.

All watches available at IWC Boutiques or on IWC.com