Damn, opposites don't attract

Study shows couples are more likely to be similar than different, which is bad news those looking for someone to complete them.

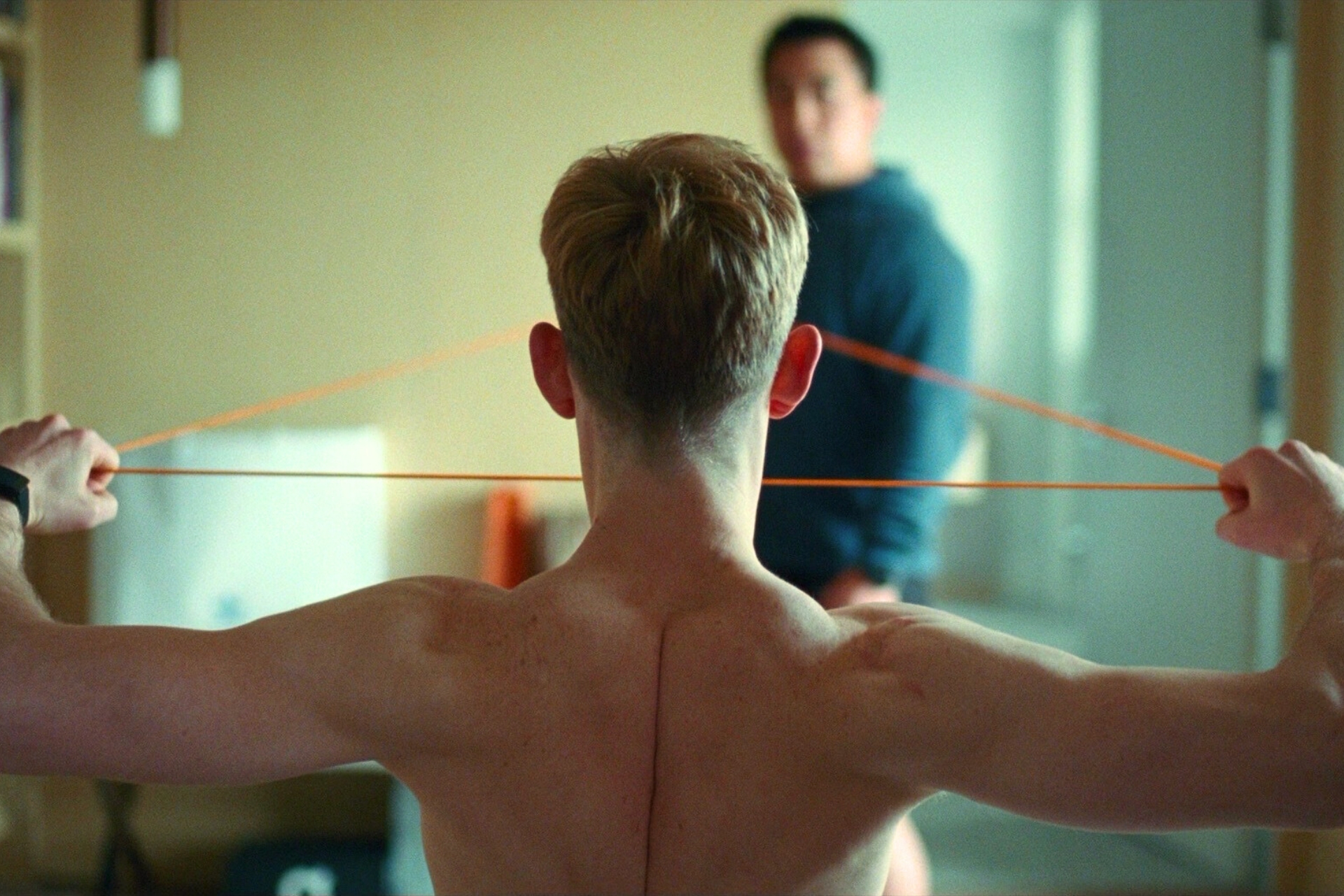

IT TURNS OUT fire and ice don’t create relationship magic… or even warm water. Science has just shredded one of the most common romantic tropes: that opposites attract. Instead, couples are defined more by their similarities than their differences.

This is obviously a blow to anyone who might have been hoping their flaws could be complemented by the strengths of another to create an impenetrable, united whole. It’s also tough for lyricists who have mined the more combustible dynamics of romantic entanglements, though, off hand, I can only think of one song that explicitly invokes the notion that opposites attract: Paul Abdul’s 1989 ‘Opposites Attract’, in which the singer and former LA Lakers cheerleader engages in a melodious tete-a-tete with an animated cat. Basically, it’s rather boring news, but science has little time for romance or pop music, for that matter.

In shooting down one common relationship trope, the study, by University of Colorado Boulder researcher Tanya Horwitz, has elevated another: “Birds of a feather are indeed more likely to flock together,” says Horwitz, showing lab coats, despite being coldly clinical killjoys, are partial to a cliche.

In the study, scientists reviewed previous research on how similar or dissimilar couples tended to be, covering 22 traits across nearly 200 papers involving millions of male-female partnerships dating back to 1903. They then followed up with a fresh analysis of 133 traits in nearly 80,000 opposite-sex couples enrolled in the UK Biobank project, finding between 82 and 89 per cent of traits examined were similar among partners, with only three per cent ranking as substantially different. Because behaviour may differ for same-sex couples, the scientists are investigating these relationships separately.

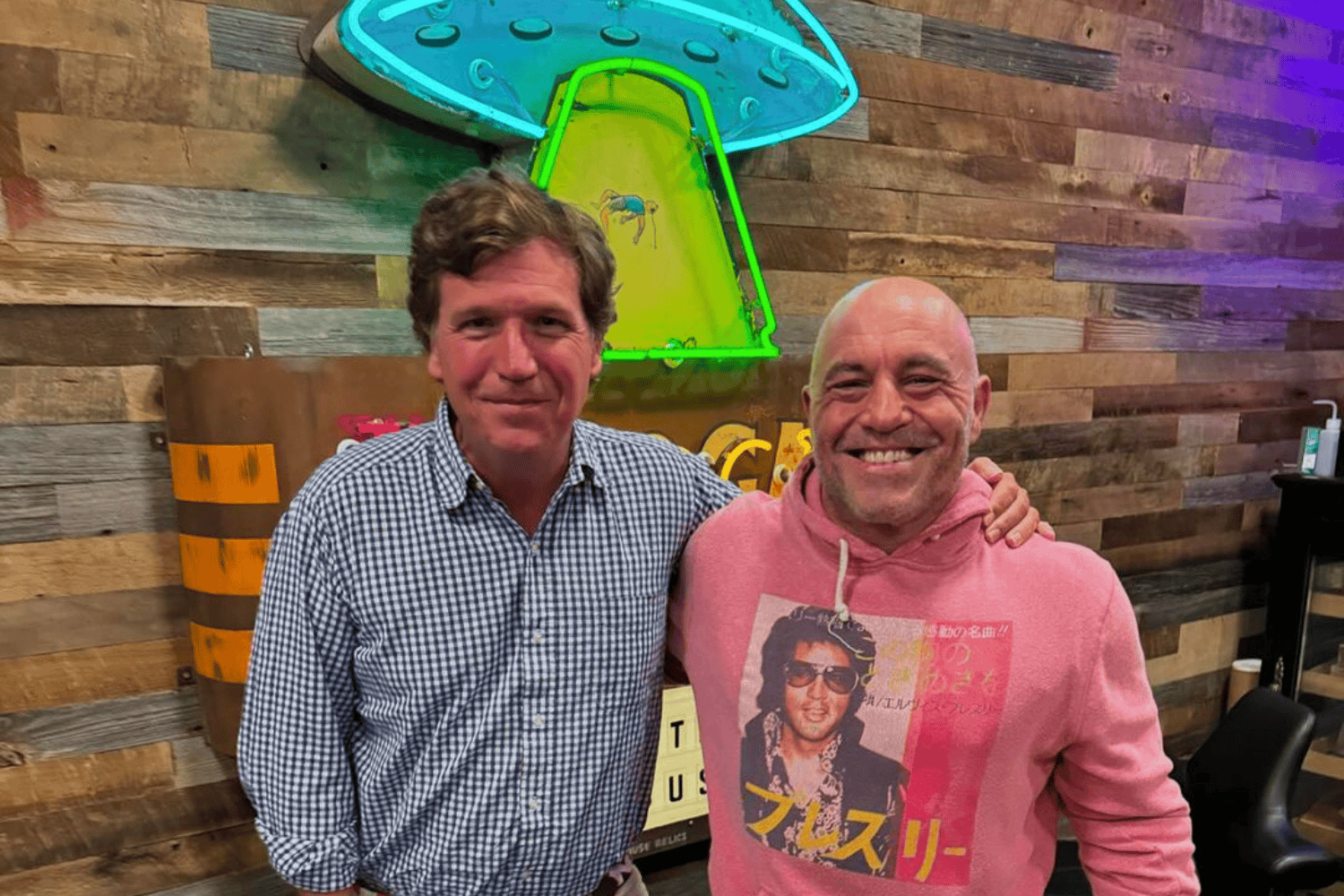

Horwitz and her colleagues found couples largely matched across a range of traits including political and religious views, levels of education and some measures of IQ. Heavy smokers, heavy drinkers and teetotallers all tended to partner up with people who shared their habits.

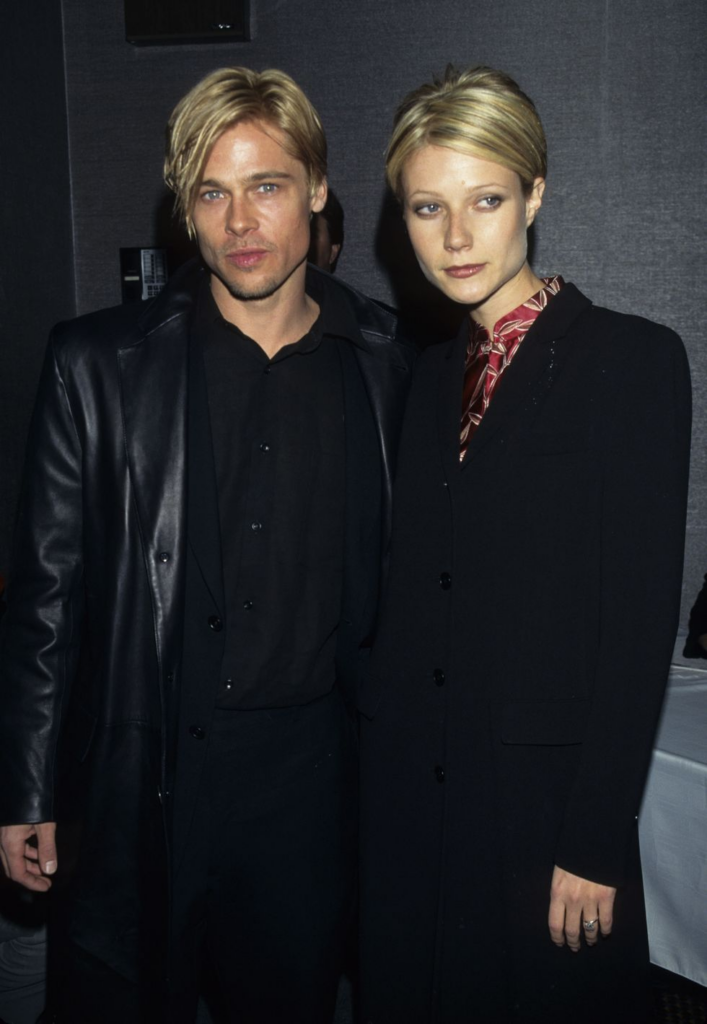

But couples did not match across the board. Height, weight, medical problems and personality traits all varied among couples. Extroverts were not more likely to choose other extroverts over introverts. “The fact of the matter is that it’s like flipping a coin,” Horwitz says.

Couples were likely to share a similar birth year, and intriguingly, show similarities in things like the number of sexual partners they’d had and whether they were breastfed as a baby. When opposites did appear to attract, the associations were often weak. This was seen in early risers pairing with night owls, left-handed people with right-handed, and those who have a tendency to worry with those who don’t.

So, are there any lessons to be drawn from this? Essentially, romantic love is not the wide open, thrillingly random crap shoot we often believe it to be. The reality is that in the dating pool we’re all fish and, as such, likely to be attracted to other fish in the same pool—actually, let’s call it a pond. These fish could be shy or outgoing, daring or risk averse but the bottom line is you’re still likely to end up with a fish, rather than say, an octopus. You might fantasise about being with an octopus but the likelihood is you’ll probably still end up with a fish, maybe a carp.

This doesn’t mean that serendipity and the ‘cosmic connection’ you might feel upon a chance encounter with a stranger does not have its place: if I hadn’t decided to get on that train on the Hungarian/Slovenian border I’d never have met Olga. It’s just that if you stay with Olga, it’s likely because despite coming from opposite ends of the Earth, you are probably still similar in terms of your backgrounds; culturally, demographically, politically, and socially.

Of course, the natural tendency when faced with a slap from science’s cold clinical hand is to immediately look at your own relationships and try to counter the data amassed from 80,000 couples with a solitary piece of anecdotal evidence from your own life. Something like, ‘Well that doesn’t make sense, I’m reserved and my partner’s a show-off’ or ‘I like Chinese food and my partner can’t stand it’.

Give it up, in the areas that count, you are still both fish. You both probably went to the same type of school, have similar political leanings, and care about the same causes (banning fishing perhaps?). These are the reasons you likely stayed together, even if you weren’t consciously aware of these factors.

“Even in situations where we feel like we have a choice about our relationships, there may be mechanisms happening behind the scenes of which we aren’t fully aware,” Horwitz says.

Of course, you could match with an octopus on a dating app (watch out, those things are players), but in that case it’s likely that your differences will eventually see things fizzle out–it’s tough when one party can eat with their hands and the other must rely solely on its mouth.

Choosing partners with whom you have common ground could have future consequences, the researchers say. If taller people pair up with other taller people, and shorter people with other shorter people, future generations could have more individuals at either end of the height spectrum.

Similarly, previous studies have found people increasingly pair up with others with similar levels of education—a Ph.D. student would never date a mere honours student, for example. Jokes aside, this does raise the possibility of greater division and widening inequality.

But you’re just a fish and, as it stands, you’re probably best to continue to swim about in your pond with a smile on your face and spring in your fins. In all likelihood you’ll find exactly what you’re looking for.

Related: