What comes after sneakers and gorpcore?

The glory days of gorpcore, where sneakers and outdoorsy brands ruled, are coming to a close. Which begs the question: what will be the next big movement in menswear?

IF YOU THINK ABOUT the last decade in menswear, three major movements stand out: sneaker culture, streetwear and, most recently, gorpcore. But really, gorpcore wouldn’t exist without its drop-obsessed forefathers; sneakerheads transformed menswear from a humble clothing category into a thriving subculture that, according to recent estimates, was expected to grow faster than its womenswear counterparts in the years leading up to 2026. Blame it on the economy, but it feels like the core market that was propelling that growth — sneakerheads and streetwear fans, mainly — have either moved on from the scene, or vastly curbed their levels of consumption.

Recently, I was speaking with friends who work with a well-known Australian retailer. They admitted they’ve been wondering a similar thing: where did that core sneaker customer go? They said that years ago, the retailer’s bestselling brand was Nike — by a country mile. These days, it changes from month to month. When I asked why they thought demand for Nike had fluctuated among their customers like this, they hypothesised a shift in consumer habits. People are still buying Nike, and sneakers more broadly. The main difference is we’re buying far less of them. Unlike how we did in 2015, we’re not treating sneakers as collectables that sit on our shelves like objects in a museum. Just like we would any other pair of shoes, we’re simply buying one pair that we actually plan to wear.

Like most trends, collectables that secure you clout among your peers — whether it be Pokemon cards, comic books or high fashion sneakers — come in and out of fashion. While diehard sports fans have been collecting shoes worn by their favourite athletes for decades, fashion sneakers didn’t become collectible items until the 2010s, when luxury designers like Raf Simons began to collaborate with sportswear brands like Adidas, and big celebrities like Kanye West and Pharrell launched their own highly anticipated sneaker lines.

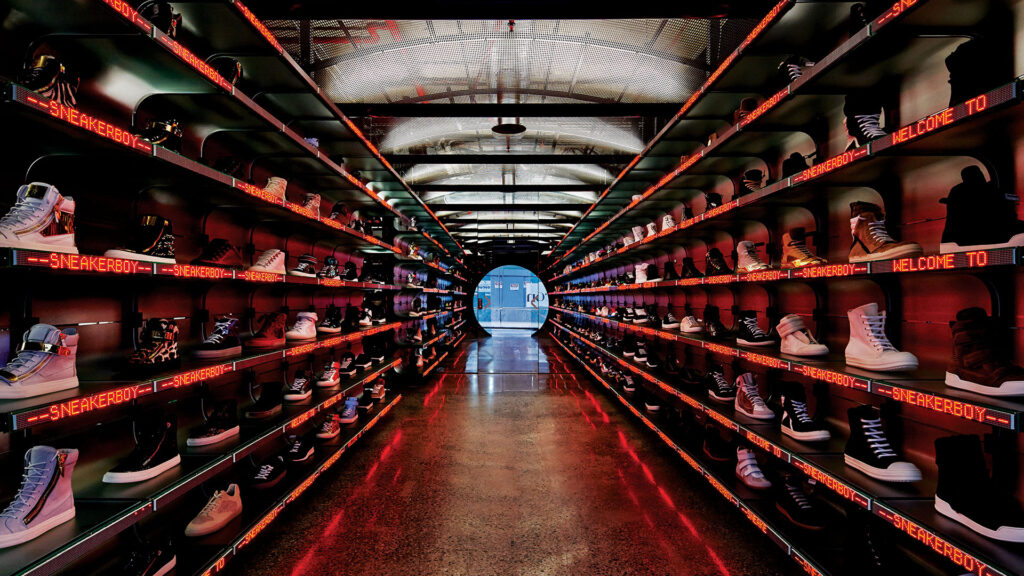

It was around this time that Sneakerboy, a trailblazing Australian retailer in the sneaker and streetwear space, opened its first store in Melbourne. I recently wrote a story about the rise and fall of Sneakerboy, which shut down in 2022. The reason for its demise was multifaceted. But Sneakerboy was world-renowned for stocking niche and highly collectible sneakers, and selling them via drops that people would queue up around the block for.

Years on, a lot about sneaker culture has changed. A decade ago, Margiela high tops were in hot demand (one former Sneakerboy employee I spoke to referred to them as “liquid gold” among fraudulent sneaker resellers), but as they became more accessible, their lustre wore off and demand for them dropped. This happened to a lot of brands and styles — as sneaker culture grew from a niche community into one of fashion’s most influential markets, previously rare models became mass produced. And when something becomes mass, it loses its appeal among savvy collectors.

“When I first started, there was this real sense of community around [sneaker culture]. The same people would go to every launch, and we’d talk about construction and creation and the collabs,” Nick Gray, a retail specialist and the former buying director of Sneakerboy, told me earlier this year. “Then it became all about the ‘cop and flip’. So it was about buying sneakers and reselling them right away. It was a very different motivation . . . and there was a new launch every other week. Customers just couldn’t keep up.”

Gray thinks that now, we’ve “moved to a place where it’s quality over quantity”. In other words, sneakerheads don’t have that insatiable desire to collect anymore. Because firstly, collecting sneakers is no longer the clout-securing exercise it used to be. And secondly, the economy doesn’t really encourage it. It’s quite funny to think that the cost of living has forced us to downgrade sneakers from collectible items we’d keep box fresh, to their intended purpose: functional products we buy to wear.

The brands dominating the sneaker space have changed too, with smaller, nicher brands coming for Nike and Adidas’ market share. By taking the approach of tapping zeitgeisty menswear brands, designers and retailers like Aime Leon Dore, Salehe Bembury and Bodega, New Balance has positioned itself as a really cool brand (its recent collaboration with Miu Miu has also been a massive hit). As streetwear matured into gorpcore, Salomon, with its outdoorsy identity, received a huge glow-up. The rise of run clubs has seen brands like Hoka and On enter new spaces, too.

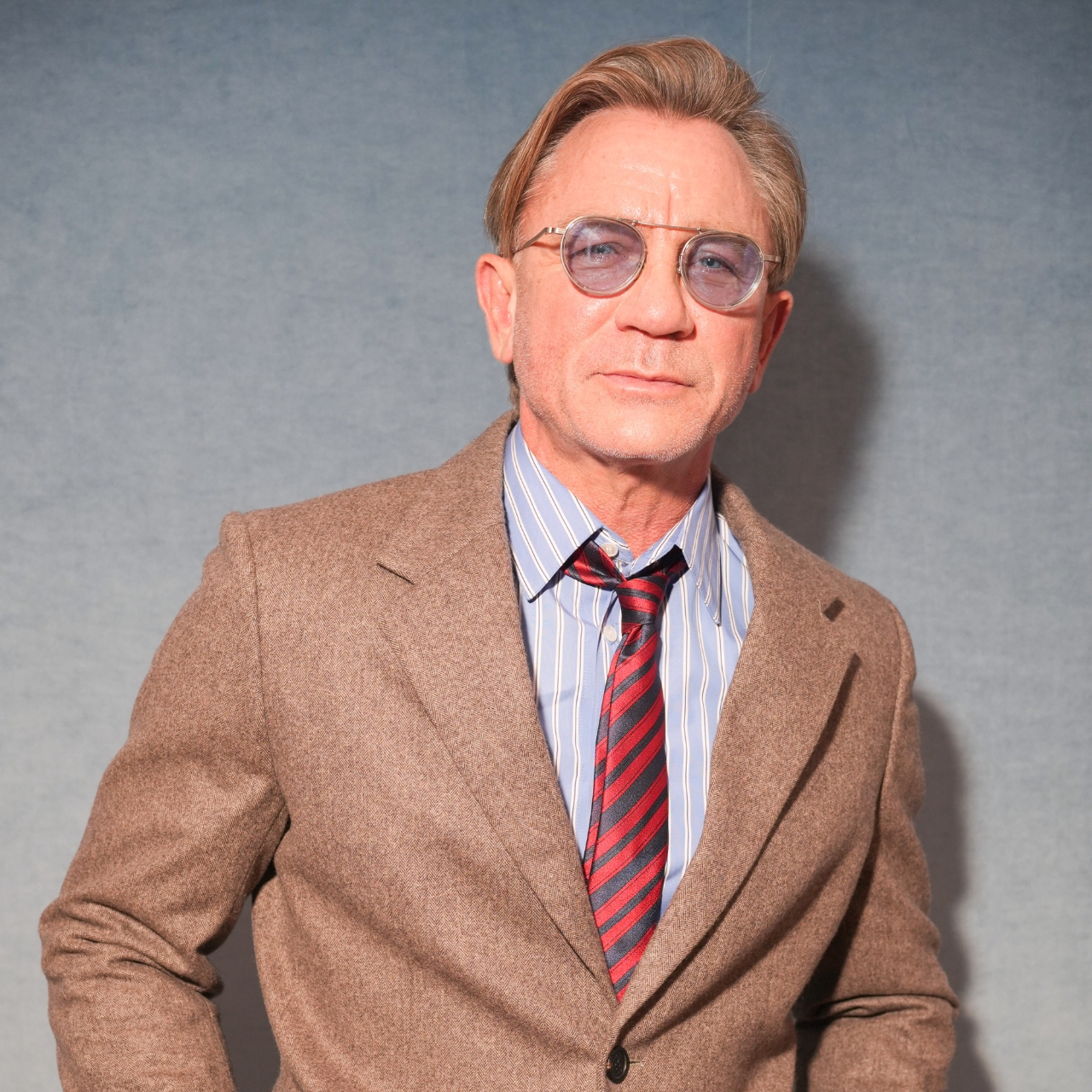

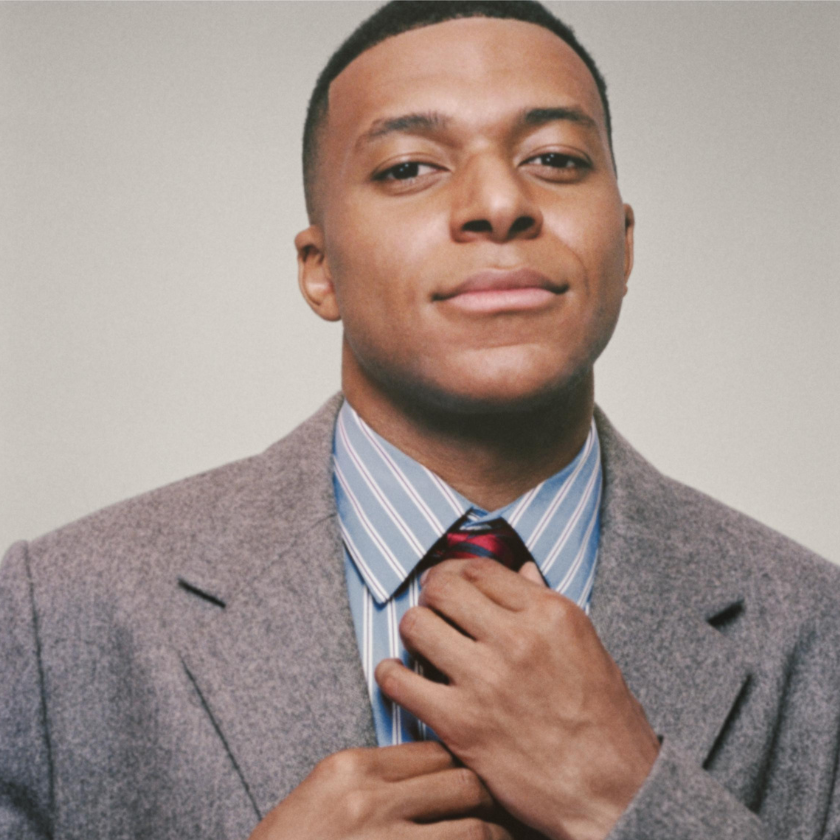

At the recent menswear shows in Milan and Paris, there were very few sneakers to be seen on the runway and even the streets. Save for Wales Bonner, which debuted its new high-top Superstar, most designers proposed loafers, brogues and sandals. There wasn’t a great deal of gorpcore on show either. The looks were more wearable; tailoring was more prominent and everything felt very classic (some might say safe). As we move into a post-gorpcore world, it seems like menswear is wondering what to do with itself, and what comes next. And while a return to tailoring is a nice thought, it’s hard to imagine sneakerhead-levels of hype forming around nice double breasted jackets, box pleat pants and brogues.

But maybe someone once said the same thing about sneakers?

Related: