Why the art world is paying attention to Australia

When it comes to the due recognition of First Nations art internationally, Australia is setting the precedent. As the inaugural curator of a pioneering new project at the 24th Biennale of Sydney, Tony Albert has a few ideas about why.

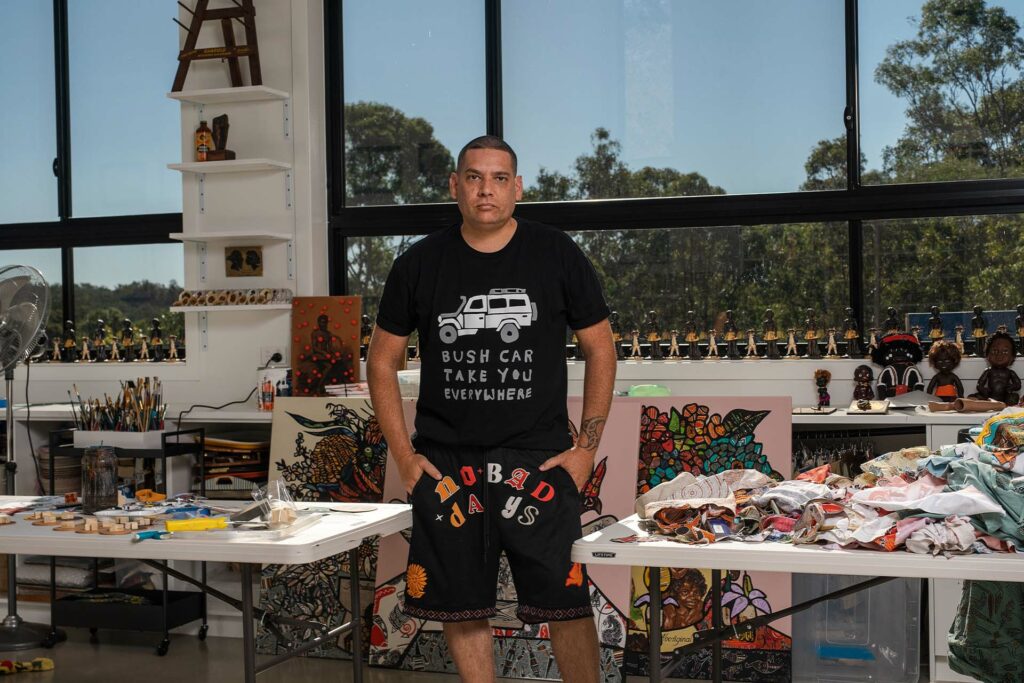

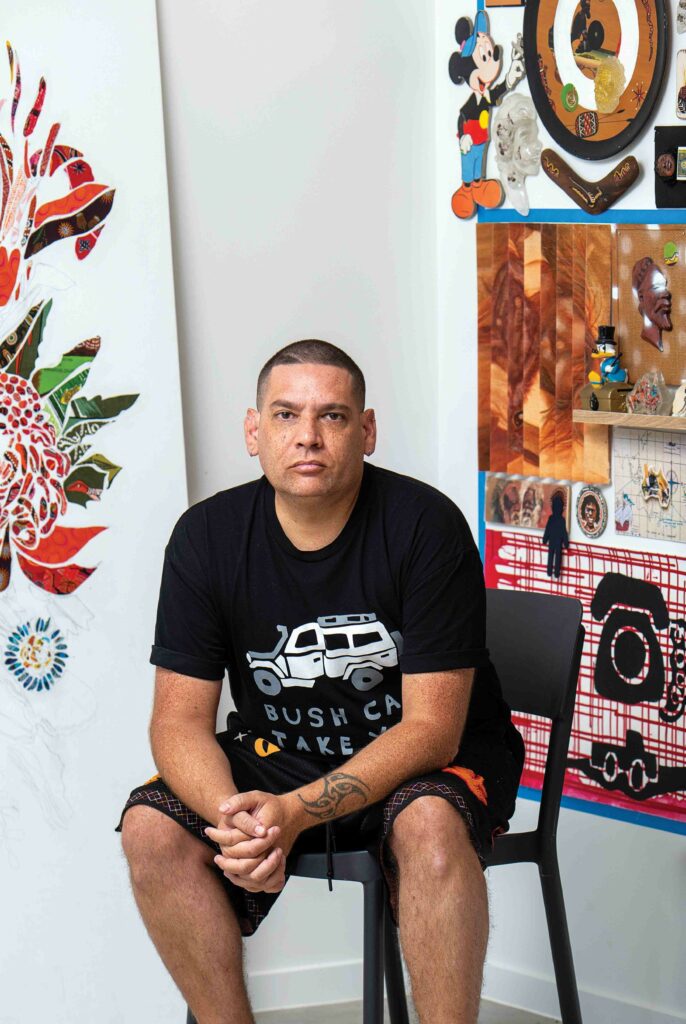

TONY ALBERT IS USUALLY the one making the art. This time four years ago, the acclaimed Girramay, Yidinji and Kuku-Yalanji artist from Townsville was putting the finishing touches on Healing Land, Remembering Country, a sustainable greenhouse on Cockatoo Island for ‘NIRIN’, the 22nd Biennale of Sydney. But this year, the artist known for his poignant and often satirical interrogations of Australia’s colonial legacies, will play a different role in the proceedings. As the inaugural First Nations Curatorial Fellow, a position that stems from a partnership between the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain—an art gallery and foundation established by Cartier in 1984—and the Sydney Biennale, Albert has spent the past months helping to bring the visions of 14 First Nations artists from all over the world to life in time for the 24th Biennale.

Operating in this capacity feels intuitive for Albert—he’s always enjoyed working with emerging Indigenous artists, and regularly uses his own platform to promote the storytelling of others. Albert has dedicated part of his current solo show The Garden + Forbidden Fruit at Sydney’s Sullivan+Strumpf gallery to The Preview, an exhibition of new works by emerging First Nations artists Aidan Hartshorn, Keemon Willams and Erica Muriata, which he curated with the intention of inviting greater exposure to their work.

The opportunity to do this on a stage as big as the Biennale, then, is not lost on the artist—especially when First Nations art and Indigenous knowledge systems are receiving more attention on the world stage than ever before, as the need for climate action becomes not only clear but urgent.

Ahead of the 2024 Sydney Biennale, Ten Thousand Suns, we sat down with Albert to chat about the importance of paying it forward, and why right now, more and more countries are looking to Australia as an example for how to nurture, promote and elevate First Nations art.

Esquire: This is the first time the Biennale of Sydney has appointed a First Nations Curatorial Fellow in this capacity. Why is the role so significant?

Tony Albert: I really see it as a commitment to long-term engagement. It’s an ongoing relationship that allows someone to be that conduit between the Sydney Biennale, the artist and Fondation Cartier, as well as an advocate and spokesperson for the commissioned artists— someone who can really elevate, push and support Indigenous art within the Biennale framework while making sure there’s appropriate cultural protocols and nuances in place. But also, it’s also about looking at the artists’ visions, and connecting them with new mediums and the right people… bringing options to them that aren’t necessarily available in their communities.

And the artists involved aren’t just Australian.

Exactly. This is about understanding that these incredible nuances we share with our brothers and sisters extend much further than just the confines of our borders. It’s part of a global movement that is pushing First Nation’s voices and ideas to the forefront.

Can you tell us more about this global movement—why is it happening right now?

I think climate has a lot to do with it. Indigenous people all over the world have maintained the environment and cared for the country since time immemorial, and we really have to start rethinking the way we view the environment—it’s less about ownership and more about belonging. People are reaching for those conversations, and they exist within Indigenous communities and have done so for thousands of years. We’ve contributed the least to the situation we’re in, yet as people who often live remotely and rurally or on the fringe of society, we’re more often than not the first to feel these kinds of severe impacts: the loss of animals, totems, changing sea levels. These are really big, important conversations that extend beyond our own borders; they’re one thing we have in common and art is an incredible visual voice. It allows us to interact with people in a way that’s not giving lectures, or yelling and screaming at them. Art gives us a chance to engage, to feel involved and be part of something.

You’re typically contributing to these conversations as an artist. What do you enjoy about taking part as a curator and mentor?

I enjoy it immensely. Artists are my heroes; they are so courageous. And as an artist myself, I know that when you have a team that can really push you to make your work as best as possible, it’s so helpful. And for me, no request goes unanswered—it’s all those things I know and understand, whether it’s connecting artists with foundries or the best fabricator or, in the case of [Bard, Noongar artist] Darrell Sibosado, someone who can do electrics for light work. I can go, ‘oh, we have to call aunty so-and-so, or uncle so-and so, and we can make that happen’. Just within the framework with aboriginal art, sometimes those requests are a little… weirder. Like, you might need emu feathers.

The profile of Indigenous Australian art is growing on the world stage—the fact the Tate Modern in London is hosting the first large-scale European presentation of Anmatyerr painter Emily Kam Kngwarray’s art next year speaks volumes. What do you make of the attention?

I know from personal experience that other countries are looking to Australia and what we’re doing and the way we engage with our First Nations people. That’s not saying we’re perfect. It’s just saying we’ve actually come a long way, and we stand on the shoulders of incredible people and artists who were at a point [years ago] that other nations are at now. We know what it means to have dedicated spaces for Aboriginal art. But we also know what it means to disperse Aboriginal art throughout an entire gallery. The position we’re in [within] the art world—other countries have a lot to learn from that. So as tough as sometimes our battle is, we’ve got to look at and understand and applaud where we’ve come from.

Ones to watch: from the Torres Strait to Peru, three First Nations artists to see at this year’s Biennale

Dylan Mooney, Yuwi/Meriam Mir/South Sea Islander, Australia

“A proud Yuwi, Torres Strait and South Sea Islander man from Mackay in North Queensland, Dylan Mooney responds to community stories, current affairs and social media,” says Albert of the artist, who is legally blind. “He’s interested in the ways in which we can reframe conversations around some of the voices that have been left out.” He’s 27, yet Mooney has already made an important body of work that “embodies optimism and a shift in representation of queer love among people of colour.”

Cristina Flores Pescorán, Perú/Netherlands/USA

“Cristina Flores Pescorán’s work is a dialogue between her body, healing processes, medical experiences, family memories and feminism. Reflecting on her own experience of sickness, treatment and recovery, Flores Pescorán employs a wide range of mediums in conversation with pre-Hispanic weaving, and dyeing techniques using medicinal plants that are part of her daily diet,” says Albert. Through her practice, Flores Pescorán “reflects and challenges what we understand as illness, death, cure, nutrition, pleasure and magic in our contemporary society.”

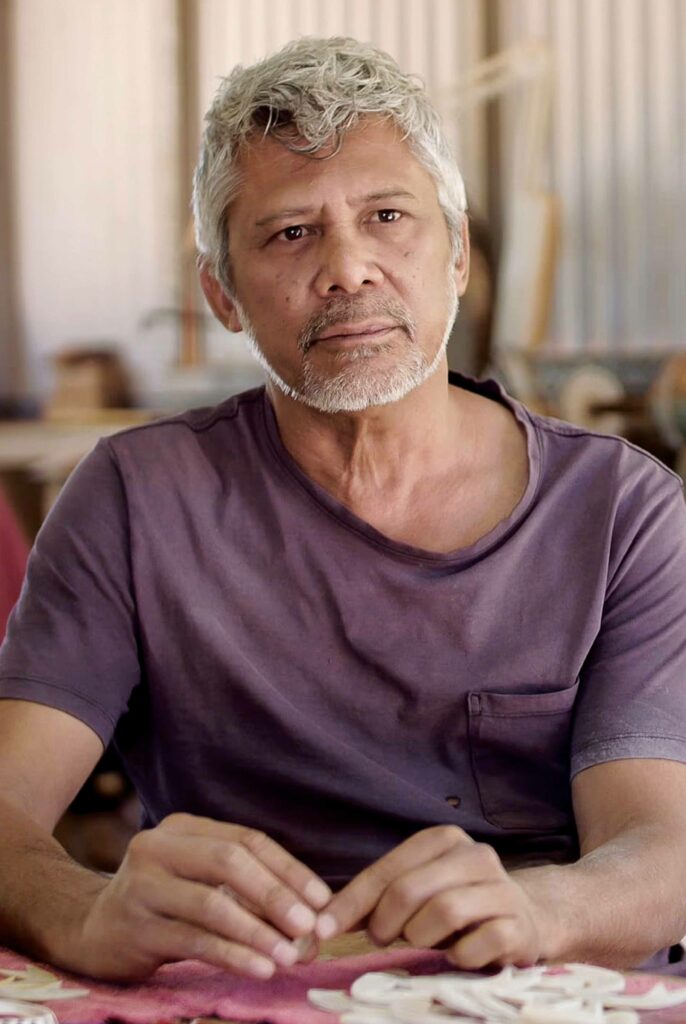

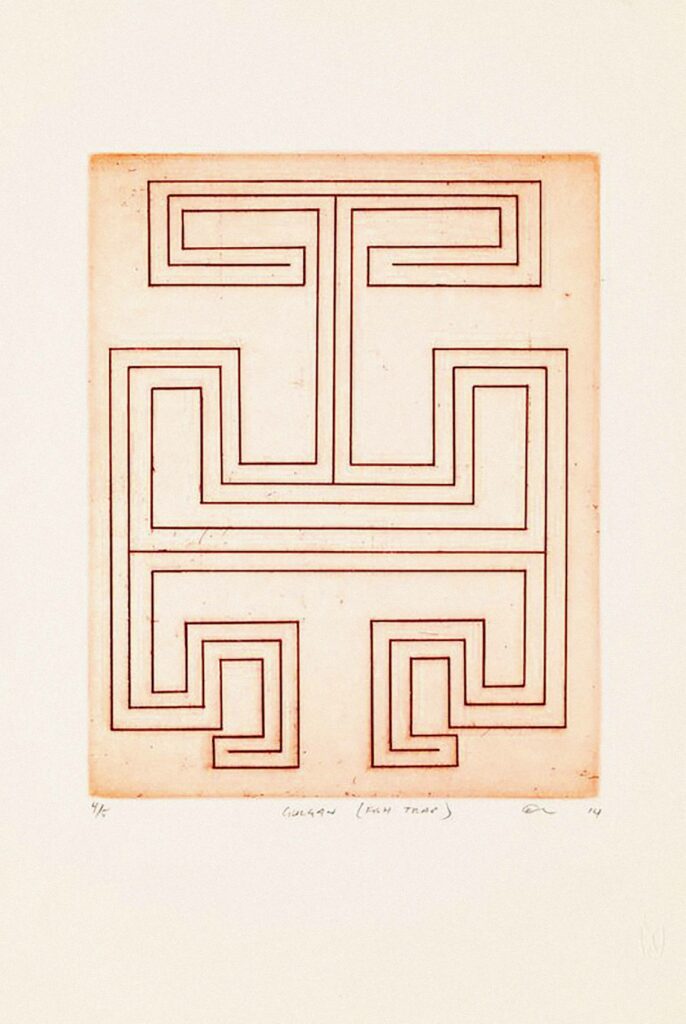

Darrell Sibosado, Bard/Noongar, Australia

“Darrell Sibosado’s practice explores the innovative potential of riji (pearl shell) designs within a contemporary context. Passed down over countless generations, the designs represent the detached scales of Aalingoon, the Rainbow Snake,” says Albert. Through his printmaking and installations, Sibosado reflects

on traditional Bard lore “and is intent on reiterating that Aboriginal culture is a living, adaptive culture that undeniably commands a presence in the contemporary space.”

Related:

Vincent Namatjira on humour, visiting the King and why fame is the aim

90 years of Esquire: the most memorable covers, stories and scandals