Umi Nori, Australia’s ‘anti dapper’ tailors

Zi Nori and Roman Jody are cultivating a new look for Australian men. Rappers, artists, actors – and regular guys – can’t get enough

WHEN ZI NORI decided to start his own tailoring brand, he had just finished a year and a half sentence of house arrest. He had been charged with commercial supply, which forced him to give up his tailoring apprenticeship, which he’d been working on for five years. “It was a phase of my life where I realised, ‘Okay, shit’s gonna hit the fan’,” he says. “It was one of the most difficult periods of my life, going through all that with my family and dealing with the court system. It was definitely one of the biggest life lessons I’ve ever had.”

But while taking time to reevaluate, Nori’s phone kept ringing. It was former clients from his old job. They wanted new suits, they wanted to know when he’d be making them again, and where. “I needed to make sure I didn’t lose my mind,” says Nori on the confines of his court order. “I realised I wanted to open a shop, I wanted to sell suits . . . I didn’t want to let what happened to me define my future . . . But I didn’t know the first thing about marketing.”

So Nori reached out to Roman Jody, founder and designer of Jody Just and an old high school mate. Jody had recently moved back to Australia from New York. Feeling burned out from the pace of life there, he was open to the idea of trying something new. Having studied business strategy at Parsons School of Design and creating a successful eponymous brand of his own, Jody saw the appeal of a slower, craft-focused approach to building a brand.

“It was about [Zi’s] taste and service,” says Jody. “His old clients were calling [and] saying, ‘We need good service and we want to go to you. You know us’.”

Ask anyone in the tailoring industry, and they’ll tell you that service is the secret sauce; the ingredient that separates the talented from the talented and personable. Nori learned the value of it early on. It was while facing the uncertainties of graduating high school, that 17-year-old Nori took up that tailoring apprenticeship, at a small owner-operator in Sydney’s historic Queen Victoria Building. Steeped in a history of housing tradespeople and master craftsmen since 1898, the scenery made for a romantic training ground. Here, Nori learned the fundamentals: how a jacket should fit, and why trousers should drape, not hug the leg.

“He was a bit more of an old school Italian tailor,” recalls Nori of his old master. “That’s where I learned about classic suiting, and then [I] wanted to take it and put my own spin on it.”

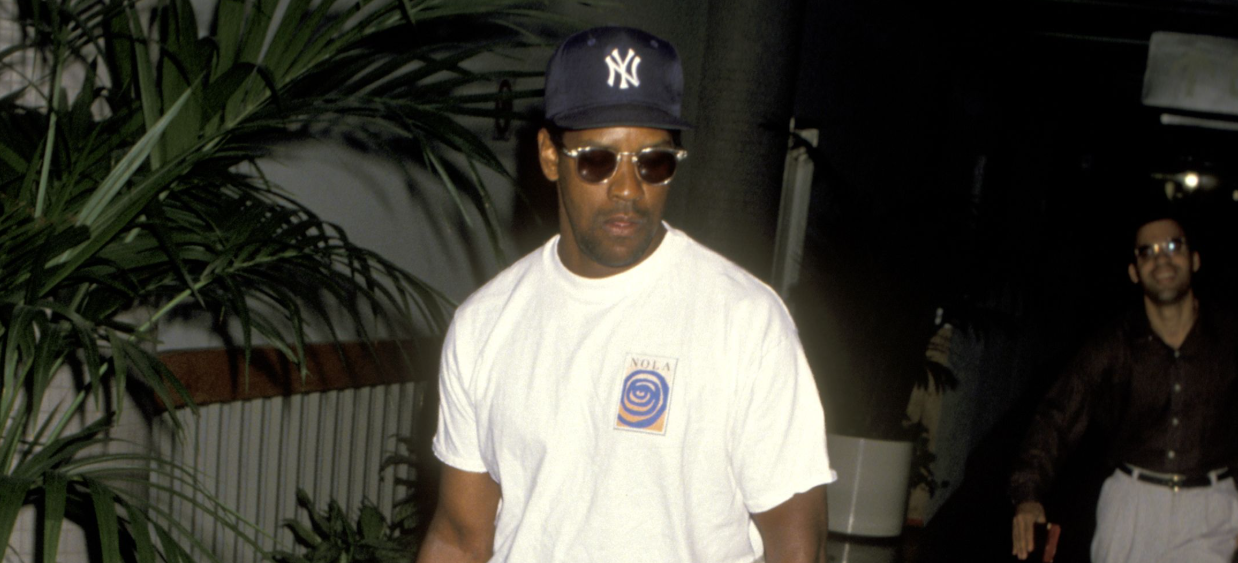

But Nori’s vision wasn’t unambitious: he wanted to cultivate a new look for Australian men. He tells me this as we sit in the Umi Nori studio, on the first floor of a Romanesque building on Sydney’s George Street, wearing a structured green single-breasted suit with wide peak lapels and a black knit tie. I tell him about my walk to the Umi Nori atelier, through the corporate heartland of Martin Place, where tight, navy blue suits are the unofficial uniform. One businessman was having steak for lunch at a pub I passed; as he tensed his arms to hack away at the piece of meat in front of him, the seams of his jacket ruched in all the wrong places.

“It’s the epidemic of tight suits,” says Nori with a chuckle. “I have to fight tooth and nail with my boys from Bankstown when they come in and they want their pants like this.” He lifts his left leg in the air, pulling at his perfectly draped trousers to reveal his ankle and calf in demonstration. “Super short, super tight. And I’m just like, ‘I’m not gonna do it . . . I always used to say Australian men only wear clothes so that they don’t walk around naked.”

AUSTRALIA HAS NEVER BEEN a nation known for its fashion, at least not menswear, where we’ve developed a real urge – a fear – of standing out or trying too hard.

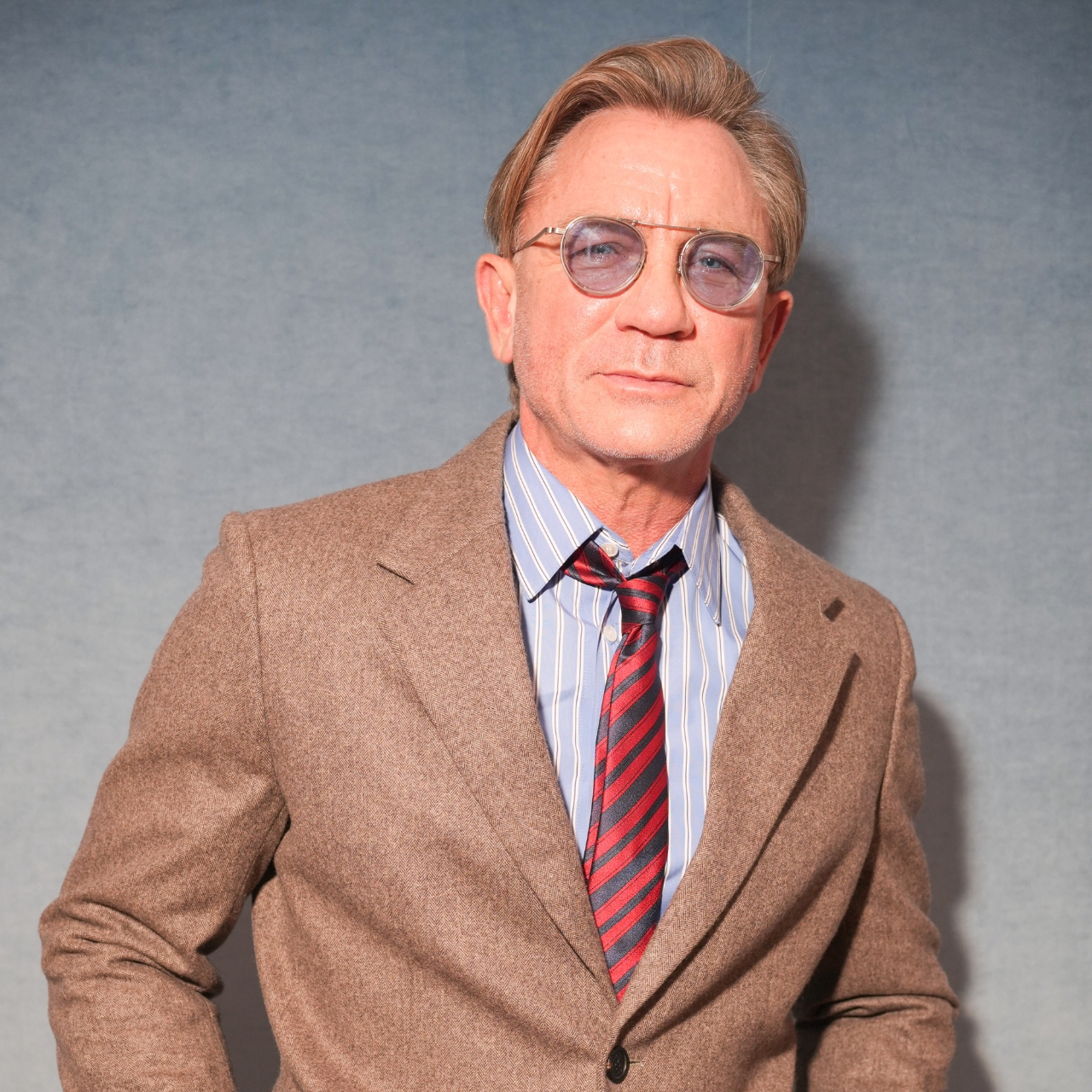

“We’re constantly having these conversations with people,” says Jody. Now five years into running Umi Nori, what sets the duo apart from the competition is how they introduce their clients, many of whom become friends, to new things – beyond thinner lapels and calf-clinging trousers. Again, a lot of it comes down to service. “A big part of what you do in the store is to fill this nurturing and educational role for people,” says Jody. “We want to do something accessible, where it’s not daunting.”

In the six collections they’ve released so far, the most defining detail of Umi Nori is the wide peak lapel. I point this out to Nori, who nods. “But some people think they’re this crazy thing,” he says. One jacket hanging in the studio has peak lapels so large, so spread out, that its fangs almost touch its shoulders. “I’m just a fucking big fan of wide lapels,” he laughs, before calmly persuading me to try it. “It’s a very traditional suiting thing. You go back to the 1920s, the wide lapel was the way to wear a suit.”

Nori delivers his expansive knowledge of fashion history – and why things look good and bad – like a true craftsman who genuinely wants to share his knowledge. He wants to “explain why you should [wear something], and why it looks great. People need that push sometimes . . . tailoring is such a master craft, and it’s a dying one.

“I’d say ninety-five percent of people who come through know close to zero about suits,” he adds. “And they end up leaving saying, ‘I actually know a bit more now.’ And once they know more it makes them keen and interested . . . paying attention to these details.”

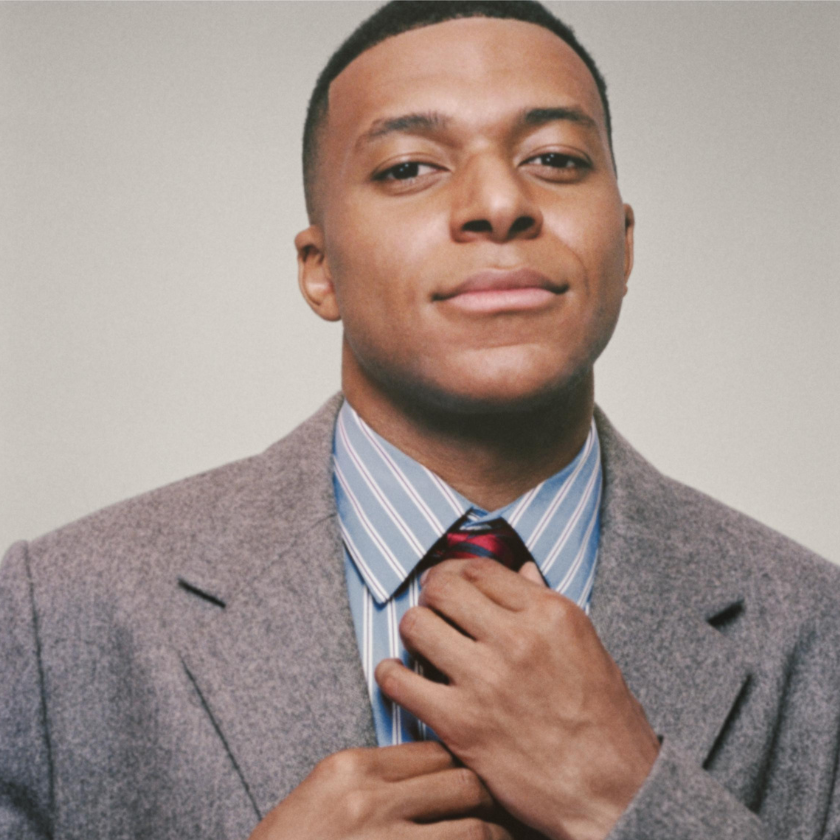

Umi Nori’s clients agree. “[It’s] such a good vibe to go into Umi Nori and hang out,” says artist Shaun Daniel Allen, a customer turned friend of the brand, who also modelled in its spring/summer 2023 campaign. “I don’t know all the ins and outs of suits and tailoring, so it’s nice to have someone who does, and [who] wants to steer me in the right direction without making me feel silly for not knowing.” This is particularly important with tailoring, where certain codes like the wrong fabric for the wrong occasion can leave you feeling exposed.

Daniel Allen wears his Umi Nori suits – particularly a deconstructed khaki cotton one – to his shows and dinners. He seems to find a sense of liberation in the flexibility of his Umi Nori creations. “It fits my lifestyle because I’m probably jumping from so many different things in the evening. I can scrub from and leave the studio and not have to over think what I’m pulling out of the closet.”

This community of creative types is something Nori and Jody are proud of. It’s also a testament to their approach, where tailoring is a form of self-investment. A two-piece made-to-measure suit – one where your measurements are taken and are adjusted to an existing design – can start at $1,400. Whereas bespoke – an haute couture-adjacent for men, given how rigorous the process is – starts at $3,000. And guys are willing to fork out the funds. As hype-culture continues to taper out, tailoring has regained considerable interest. Not dissimilar to streetwear, it’s a community-first subculture with a bottomless pool of supply and knowledge.

NORI GREW UP in the working-class suburb of Bankstown, in Sydney’s south-west. A microcosm of Australian multiculturalism, this was where his Malaysian father and Australian mother settled down in the late-1980s, after meeting as students at the University of Newcastle and later marrying. In Malay, ‘Umi Nori’ translates to ‘the mother of the Nori family’. “I love my mother to bits, so that just made sense . . . My family has been on such a journey with me these past few years . . . I wanted to honour that. And a lot of the photos we have hanging are connected to my family – but not this one,” says Nori as he jokingly points to a Juergen Teller photograph of a young Kate Moss with pink hair in bed. But next to it, a photograph that captures three generations of Nori’s father’s family makes it clear that style and taste didn’t just begin with him.

Compared to their competitors, Umi Nori maintains that their price point is accessible, especially when you take into consideration their level of expertise and service, coupled with their approachable, community-minded approach. But also, they believe it’s their ‘anti dapper’ ethos that brings guys in, and makes them feel at home with the process. When you come to the atelier for a fitting, you won’t be expected to drink whiskey on the rocks and talk about football (of course, you can if you’d like), and the walls are peppered with work by contemporary street artists, curated by Jody, who half-jokingly refers to himself as the “chief vibes officer”. While Nori is wearing a suit for our conversation today, usually, he’ll be measuring you up in his favourite pair of jeans.

“I’m so happy with how far we’ve come,” observes Nori. “We’ve become disruptors in this industry.” Jody echoes: “We’re just cultivating a community that is really authentic and shares a common interest, which is really an appreciation for clothes and art.”

Opening image photography by Matt Wilson.

Related:

From metalheads to club kids, every style tribe wants a piece of Jody Just