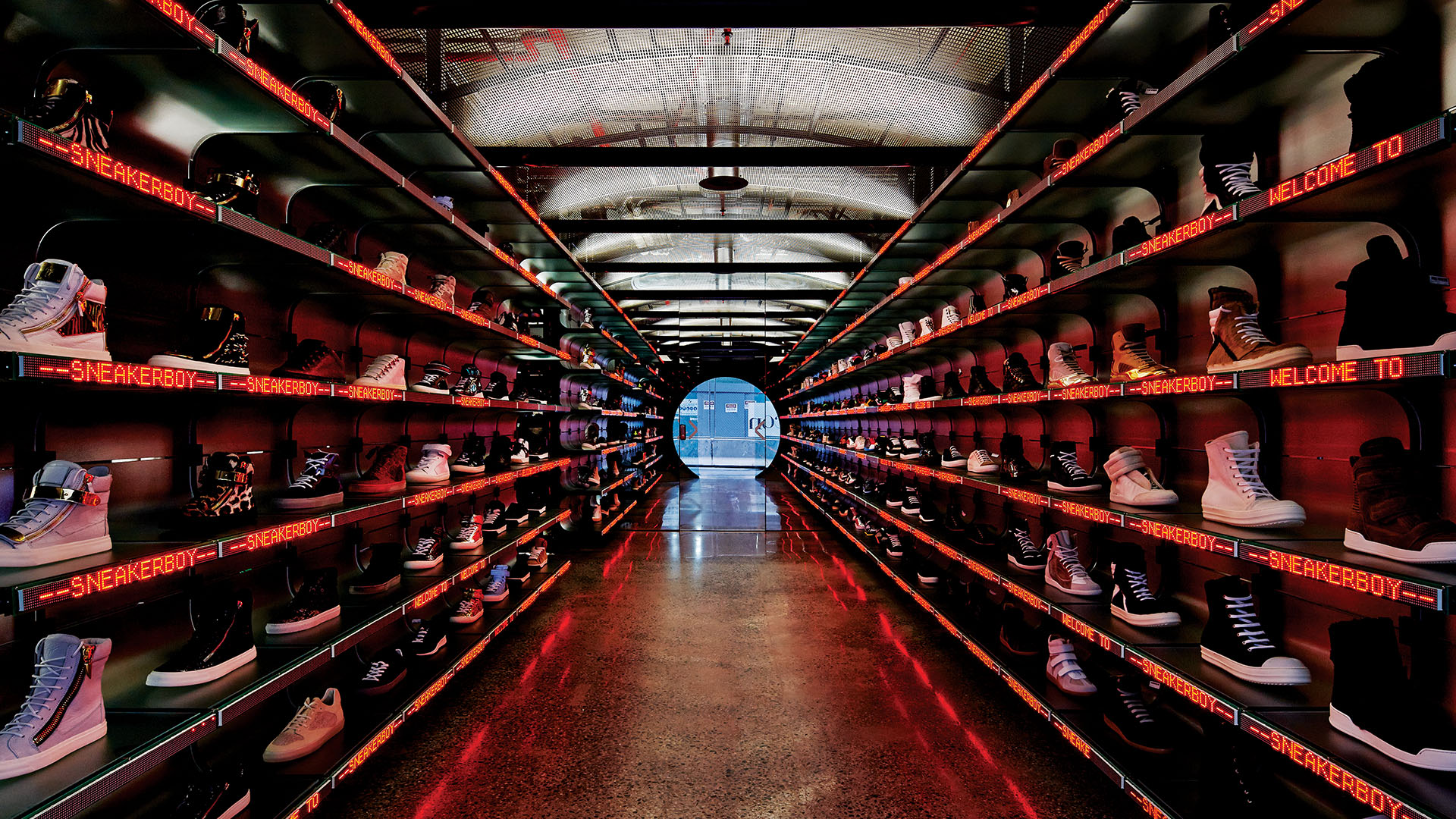

IN THE 2010s, if you had an interest in sneaker culture, you shopped at Sneakerboy. A destination store that sold the coolest and most exclusive sneakers in the world, it was a mecca for Australian sneakerheads as well as a destination for overseas travellers. High-top styles from Balmain, Giuseppe Zanotti and Givenchy — which were the height of cool at the time — lined the walls. It also sold exclusive releases by sportswear brands like Adidas, which had only just started to penetrate the high-end fashion market, making Sneakerboy one of the first businesses in the world to suggest sports brands and luxury fashion could be worn together.

You see, before they became high-end status symbols, sneakers were shoes you played basketball in, wore unselfconsciously with bootleg jeans (if you were a dad), or, if you did wear them for looks, they were more likely to be from Converse than Prada. But in the mid-to-late aughts, the tectonic plates of fashion began to shift as luxury designers like Raf Simons, and Hedi Slimane for Dior Homme sent sneakers down their runways in Paris. In the years that followed, more avant-garde designers like Riccardo Tisci and Rick Owens added sneakers to their collections – Owens’ infamous ‘Dustulator Dunks’, which were later renamed the ‘Geobaskets’ after a reported lawsuit from Nike, became a cult hit among a group of fashion-conscious young men that would soon become known, collectively, as the most influential men’s fashion consumer in recent memory.

That consumer was the sneakerhead.

Sneakerheads were not your typical luxury customers. Though they purchased shoes from high-end brands, those who lived and breathed idiosyncratic lace-ups tended to be younger and internet savvy, and they treated their purchases like collectible items, much like women might with handbags. The rarer the sneakers you owned, the more clout you could secure among your peers. To ‘cop’ at ‘drops’ – that is, secure rare sneakers at launch events – wasn’t just a form of retail therapy; it was a lifestyle.

Ironically, for an industry that trades in trends, fashion can be famously slow to adopt change – at first, the sight of sports shoes on the runway caused many legacy fashion editors to clutch their pearls. But in Melbourne, a young entrepreneur by the name of Chris Kyvetos was watching this momentum build. He knew this merging of luxury fashion and sneakers wasn’t just a phase but a growing phenomenon, and, as a sneaker enthusiast himself, he saw an opportunity to be on the cutting edge of the boom. So he began to dream up what would eventually become Sneakerboy.

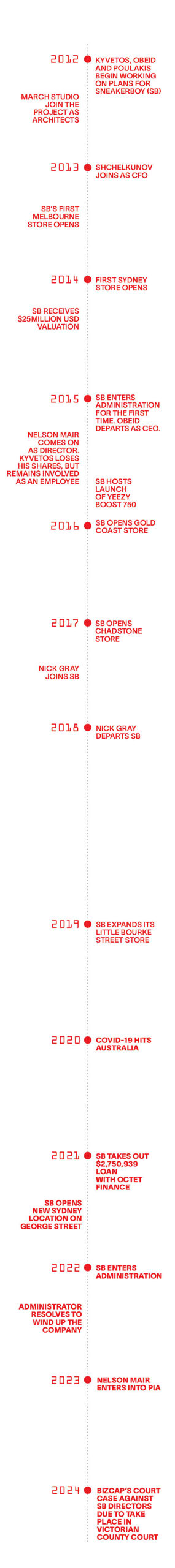

From the moment it opened its first Melbourne store in September 2013, Sneakerboy had set a precedent. In a story published months after its opening, The Business of Fashion wrote: “Sneakerboy is targeting a new generation of luxury consumers with a highly covetable selection of sneakers and an innovative digital retail model”. It had, according to the publication, started a “luxury retail revolution”.

By the end of 2013, Sneakerboy was appearing in news stories all over the world; The New York Times, Hypebeast, Wallpaper Magazine, i-D and The Financial Times all ran stories about how this business from Melbourne was changing the game. In 2014, streetwear website Highsnobiety crowned Sneakerboy the world’s best retail concept. It beat out other finalists Dover Street Market, Colette and Kith – among the coolest fashion retailers on the planet. At its peak, it had the kind of reputation whereby if Sneakerboy said something was cool, it was cool.

What could possibly go wrong?

GUY OBEID LOOKS wistful as he recalls that 2013 Business of Fashion article, and the time in which it came out. “Sneakerboy . . . it was really a world-beater,” sighs the financier.

It’s early March, roughly nine years since Obeid exited Sneakerboy. This morning, he woke before dawn to take his daughter and her friends to rowing practice. He says that after leaving Sneakerboy, he took a number of years off work to be a full-time dad; only now is he feeling ready to re-enter the professional world.

Obeid was one of Sneakerboy’s three original architects. He came on as the CEO after Kyvetos, who had worked as a buyer and creative director at luxury Australian department store Harrolds, approached him with an idea for an online sneaker business in 2012. “Chris came to me excited about establishing a website for luxury sneakers,” explains Obeid from his home in Melbourne. “I was a little negative about ‘pureplay’ online . . . I wasn’t all that happy about physical retail either. But I could see the momentum around sneakers building, and I knew the luxury segment of that was going to be a big thing.”

Obeid says he also had confidence in Kyvetos as a buyer. “He had an edge and a vision.” The third player was Theo Poulakis, a businessman who co-founded Harrolds. “Theo wouldn’t let us give him a title, but I guess you would call him a non-executive director,” said Kyvetos in that Business of Fashion interview. Obeid agrees that while Poulakis helped fund the business, he was less involved in its day-to-day operations.

It is important to note that this was 2013 – a time when retail in Australia was suffering an existential crisis. Swedish fast-fashion giant H&M’s takeover of Melbourne’s historic GPO building, which had previously housed independent retailers from Alpha60 to FAT Stores, was soon to be announced, while the rise of online shopping was threatening to destroy brick-and-mortar retail altogether (or so we thought). Taking this shifting landscape into account, Kyvetos and Obeid came up with a hybrid retail model unlike anything the fashion world had seen before. Essentially, it combined the tangibility and exposure of physical spaces with the efficiency of an e-commerce business; the best of both worlds, while removing the pain points associated with each.

Small-footprint stores, explains Obeid, were key to the success of the model. “The stores were effectively showrooms. They were small but they felt spacious, because they only contained display stock, so we had lower rent and fit-out costs.”

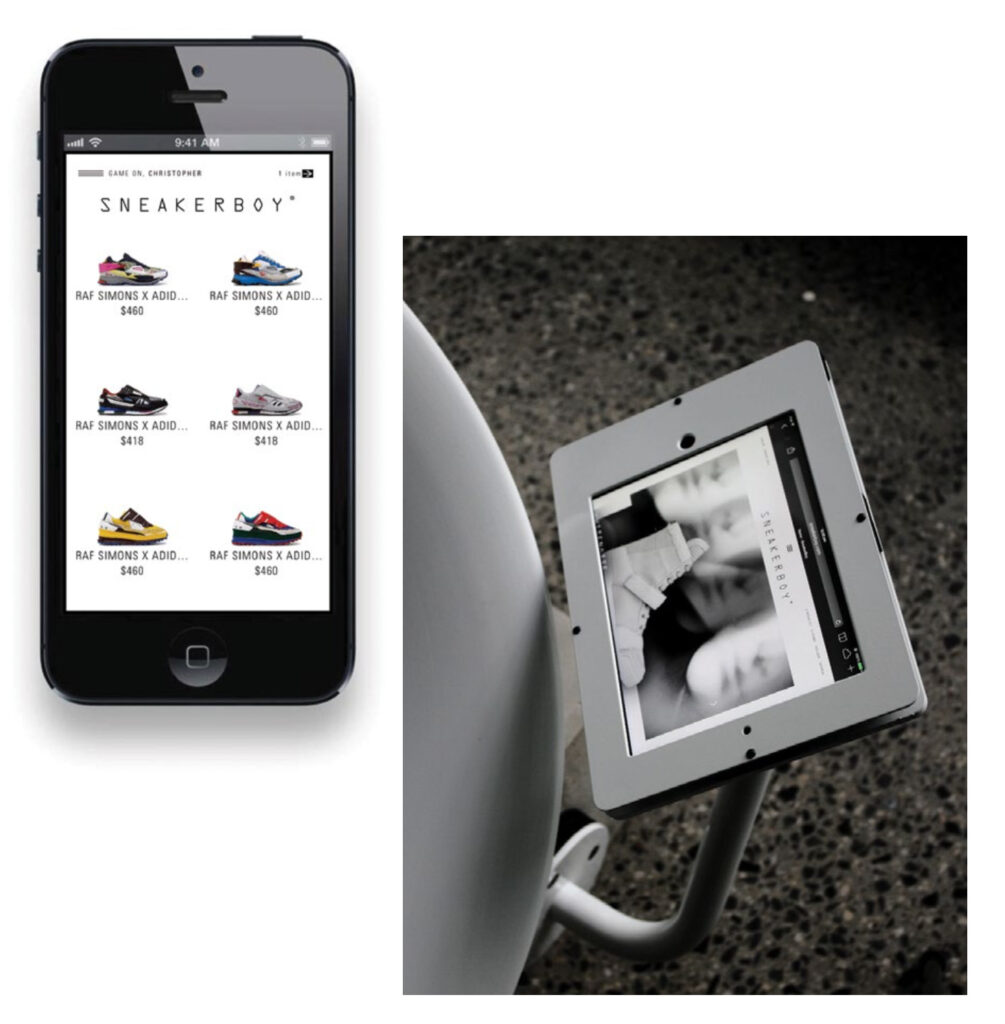

After customers tried on a pair of display shoes – the store kept only one size in every style – they would make their purchase on in-store iPads, or via the Sneakerboy app on their smartphones. Then they would leave the shop empty-handed, because, similar to how an online-only business operates, their box-fresh sneakers would be shipped to their door from a warehouse in Hong Kong within a couple of days – fast, even by today’s express-shipping standards. The iPad point of sale allowed Sneakerboy to collect data on every one of its customers, from what brands they liked to how frequently they shopped. While standard practice now, in 2013, it was ahead of its time.

Vlad Shchelkunov, a young consultant who was working for KPMG at the time, was crucial to establishing this data-collection system, as well as the business’ back end. He had been helping Obeid with the “mathematics of the whole thing”, and, when Sneakerboy was ready to open, he came on as the CFO.

“We were basically doing it on Guy’s kitchen bench. We were doing shit that no-one else has ever done before,” explains Shchelkunov when we connect on FaceTime. The ultimate complexity, he emphasises, was “there wasn’t a system that existed in the world that could account for this hybrid model. I mean, we worked with developers that had an e-comm system, and by the time we were done, I think maybe 15 or 20 per cent of the original e-comm system was remaining. Everything else was just custom built.

“To date, it beats me why no-one else is doing it,” he adds with a shrug. “The business model worked. Our little hole-in-the-wall store was way more efficient per dollar, per square metre than anywhere else. I don’t know . . . ” he trails off. “Maybe it’s the human nature of needing instant gratification. You know, ‘I want my shoes now’.”

Or maybe it’s because the eventual fate of the business overshadowed how innovative it was? “Yes, that could have something to do with it,” he acknowledges.

As the buyer, it was Kyvetos’ job to choose the shoes Sneakerboy would sell. “Chris was out in Paris with the chequebook buying sneakers, and he was very successful,” says Shchelkunov. “Chris had lived and breathed the history and key moments in the progression of luxury sneakers, so he always had a good story to tell at the right time,” echoes Obeid. While a handful of people were working on the business behind the scenes, Kyvetos became its face. As far as anyone on the outside was concerned, Kyvetos was Sneakerboy.

But with the retail model established, an intricate financial system in place and a wish list of world-renowned brands willing to back an upstart from Melbourne, it was Anne-Laure Cavigneaux of Melbourne architectural firm March Studio who, according to everyone I spoke to about Sneakerboy’s early years, brought the magic to the business. At the time, March Studios was best known for designing a number of stores for Australian skincare brand Aesop. Alongside her partner, Rodney Eggleston, Cavigneaux worked on the architecture of Sneakerboy’s first store. She was also responsible for crafting the brand’s distinctive retro-futuristic identity, which was an integral component of its cachet.

“I remember we had this phone call out of the blue, and it was Chris and Guy wanting to speak to us about Sneakerboy,” Cavigneaux tells me. “We knew that sneakers were entering a new world, and this world was high fashion, and it felt like the right time to create this conversation about how this could materialise within a store. It was something that was really intriguing to us.”

Following the successful opening of the Melbourne store on Little Bourke Street in the CBD, March Studios worked with Sneakerboy on the design of its Sydney location, which opened at the end of 2013 on Temperance Lane in the city. Like the Melbourne store, it sat discreetly in an alleyway – and its ‘if you know, you know’ location was key to its coolness. “You could feel that we were on the pulse of something that was really different,” recalls Cavigneaux. “The creative engagement, the synergy was just like . . . you couldn’t bottle that.”

The popularity of Sneakerboy grew well into 2014. “It was all going really, really well,” says Obeid. Plans to expand into Asia were afoot, and the team was ready to sign the lease on a new store in the hip New York neighbourhood of SoHo. At the beginning of 2015, Sneakerboy was turning over around $6 million a year; according to Shchelkunov, its average transaction price was $800, but certain sneakers – like a pair of python skin Balmain’s, which caused the team quite the headache at customs – retailed for around $3500. In what might be one of the biggest moments in Australian streetwear history, in February 2015, Sneakerboy hosted the Australian release of Yeezy 750 Boost, Kanye West’s first sneaker in collaboration with Adidas. On drop day, the entirety of Little Bourke Street was flooded with people; many had camped outside the Sneakerboy store for days, waiting to place an order for the highly anticipated kicks.

“It was pretty phenomenal,” says Rachel Muscat, who, as the global director of Yeezy product at Adidas at the time, worked closely with Kyvetos on the launch. “I mean, it wasn’t an international store creating this energy in Melbourne, it was a store from Melbourne creating energy internationally. ”

This small Australian business had the attention of the fashion universe, and the world at its feet. The only problem with finding the world at your feet? There is an extremely long way to fall.

THE THING WITH FASHION businesses – and fashion more generally – is that a lot of emphasis is placed on appearances. It’s not uncommon for retailers to be struggling on the inside, while maintaining a facade of success. From Outdoor Voices, the wildly popular American athleisure brand that imploded after its idealistic founder clashed with its board members, to Seafolly, the cult Australian swimwear brand that entered voluntary administration in 2020, and again in 2023, the story of ‘it’s fine until it’s not’ has been told a thousand times, and in this increasingly tough retail landscape, it’s becoming ever more common.

Months before Sneakerboy held its first Yeezy 750 Boost release, Guy Obeid arrived at Sneakerboy’s Melbourne office to find a letter from an insolvency firm.

Sneakerboy, it said, had entered into administration.

Obeid was stunned. At the time, he was one of three shareholders; he owned 45 per cent of the business, as did Poulakis, while Kyvetos owned 10 per cent. But crucially, Poulakis held the largest security interest over the business; at the outset, he had loaned Sneakerboy the most amount of money, which made him the largest secured creditor. Therefore, Poulakis had the power to appoint an administrator on his own.

Liquidator Michael Carrafa said that Sneakerboy was put into administration owing to “conflicting interests of director and shareholders”. It was then sold to “a party relating to one of the directors” for an undisclosed price. Those close to the matter estimate it was bought back by Poulakis and his new business partner for a fraction of its recent valuation, which was $39 million. That new business partner was a man named Nelson Mair.

Obeid prefers not to dwell on the specifics of how it all unfolded. But he nods to there being some “controversy around the circumstances that allowed [Poulakis] to appoint an administrator”. After the administrator was appointed and the business was re-purchased by Poulakis and Mair, Obeid was no longer CEO and he lost his shareholding.

Before the interview went on record, Obeid emails me the following statement: “The momentum of the brand was bringing in all sorts of opportunities, but of course we had some incredible pressures, and steep learning curves that come with doing something that was so far out of the norm. I think that pressure strengthened my business partner’s views on a vision for a more traditional luxury retailing model, and so that brought about a change of management and me leaving the business in 2015.”

Obeid was aware that Nelson Mair had been talking to Poulakis about Sneakerboy, and while he was shocked at the swift nature of the takeover, he wasn’t surprised when, following the buyback of the company, Sneakerboy was re-registered under a different Australian Company Number, with Mair listed as the director.

Shchelkunov, who left Sneakerboy in 2014 after being poached by another company, is less reserved when describing what he witnessed: “Greed”.

With the change of management came a dramatic change in how the business was run. “The moment it happened, the whole hybrid thing – our beautiful, first-of-its-kind, nowhere-to-be-found model – was thrown out the door,” says Shchelkunov. “They just turned it into a shitty, old-school retail store that went on to sell stuff that everyone else was selling.”

But as far as Sneakerboy’s customers were concerned, nothing had changed (when researching this story, I could find only one report online about the 2015 voluntary administration – published by SmartCompany in April 2015). People were still queuing up around the block for exclusive drops; its stores were still the places to see and be seen. While Poulakis continued to operate in the background as a financial muscle, as Shchelkunov indicates, Mair was intent on making the business bigger and better. He wanted to open more stores, secure more brands and, essentially, grow the business exponentially.

In 2016, Sneakerboy opened a new store in the upmarket Gold Coast mall Pacific Fair. In 2017, it opened another physical space in Melbourne’s Chadstone shopping centre. March Studio wasn’t asked to design either location, both of which flew in the face of the store’s original underground, back-alley ethos. In 2019, Sneakerboy took over the leases for the two storefronts adjacent to its original Little Bourke Street store, more than tripling its square meterage.

By traditional retail standards, Sneakerboy appeared to be thriving. But its unprecedented retail model had been built with small overheads in mind; now, its rent, fit-out and staffing costs were mushrooming. Despite this, it continued to expand. Meanwhile, Kyvetos remained the face of the business. As far as the general public knew, he was still involved in how the company was run.

That was the impression Nick Gray was under when he joined Sneakerboy in 2017. He had worked in senior sales positions for Adidas and Nike Australia for close to 17 years, and knew Kyvetos through his work at Nike. Gray, who was also heavily invested in sneaker culture – he once owned more than 500 pairs – was interested in the disruptive concept Kyvetos had been able to create at Sneakerboy. When the chance to join Sneakerboy as buying director arose, Gray jumped on board.

“I loved the business. I believed in the business. I loved what they were doing,” says Gray. He met with Mair a couple of times before accepting the job. “My understanding was that Nelson was a business partner and Chris was still leading and in charge and so forth,” says Gray. “But I quickly found out that wasn’t really the case at all.”

I meet Gray in a coffee shop upstairs in the Queen Victoria Building in Sydney. He’s cautious about what he wants to say and how he wants to say it; he worked under Mair at Sneakerboy for a year and a half, and clearly, it wasn’t an easy time. But he’s one of the few people I contact from Sneakerboy after the change of management in 2015 who are willing to chat on the record.

“What happened to the business – it really only happened because of the intentions of certain people, and how people within the business were treated,” he says. “I have no problem with businesses running close to the line, but there’s a line that you just don’t cross – because that’s when people get hurt.”

While Gray reported to Mair, he would see Kyvetos on his trips back to Melbourne (Kyvetos had moved to London earlier that year), and they would meet up when Gray went to Paris on buying trips. I ask whether Kyvetos talked to Gray about how involved he was (or wasn’t) in the business at that time.

“He alluded to it, and I read between the lines.” He says at the beginning he wasn’t worried about Mair’s involvement because “Nelson also had a lot of credibility in the industry. He was involved in a lot of other stuff . . . He was quite intimidating. But I just thought that was his way of doing business.” It was on a buying trip to Paris that Gray began to wonder whether, despite the image it was projecting, Sneakerboy was in trouble. He recounts a time when representatives from a popular high-end sneaker brand stocked by Sneakerboy approached him, asking why their accounts hadn’t been paid.

“I was like, ‘We haven’t had your brand in our business for 12 months’,” says Gray. He recalls another incident where a furniture supplier knocked on the door of Sneakerboy’s head office, asking why he still hadn’t been paid for the designer furniture inside. “There were a lot of illusions with Sneakerboy,” he says. “That was the biggest thing I felt towards the end. We would go to Paris, be treated like rockstars, when we were doing a lot of dodgy things.”

THEN, IN MARCH 2020, COVID HIT. Two of Sneakerboy’s biggest customer bases – international students and Asian travellers – were gone, and its sales plummeted. The timing was disastrous. The business had just invested heavily in the expansion of its Little Bourke Street store, and, having decided to close its Temperance Lane store, work on a bigger Sydney location on George Street – an upmarket retail strip notorious for its high rents – was about to start.

While the pandemic forced many businesses to halt expansion plans, Sneakerboy pushed on. Throughout the lockdowns, it continued to trade online, reopening and closing its Melbourne, Sydney and Pacific Fair stores as government restrictions allowed. But customer discontent was building. Sneakers that were ordered and paid for never arrived; customer review forums were littered with angry comments. Their emails unacknowledged, shoppers began to take matters into their own hands. Perhaps the most industrious example of fighting back involved, according to news.com.au, a customer who spent almost $50,000 on sneakers that never arrived, attaching a bike lock to the front door of Sneakerboy’s Sydney store. “She spent tens of thousands of dollars and hadn’t received her product, so it was fair enough,” an anonymous employee told the news website at the time.

Sneakerboy’s facade of success was crumbling, and it was happening in plain sight. The fashion industry, once so enamoured by the business, watched on in confusion. That June, Sneakerboy held a giant ‘end of season’ sale, heavily discounting sneakers by brands from Salomon to Nike. Weeks later, customers who purchased stock that hadn’t yet arrived received an email explaining that it probably never would.

In July 2022, the Australian Securities and Investments (ASIC) published a notice announcing that Sneakerboy (and four other related entities) were entering administration. The business had defaulted on its loan to Octet Finance, from which it had borrowed $2,750,939 around the time of the opening of its George Street store. As a secured creditor of the company, the Sydney-based financier had appointed an external administrator, Stephen Dixon from insolvency firm Hamilton Murphy Advisory, to investigate its financial issues.

Dixon filed his administrator’s report with ASIC on September 21. Running to almost 60 pages, it laid bare a business in financial ruin. In terms of debt, what it owed Octet was only the tip of the iceberg. Sneakerboy owed big money to a number of companies, including another lender, a related entity and global brands like Nike, which was one of its biggest sneaker suppliers. It also owed money to employees. This was one of the most widely reported issues at the time of its implosion: staff were owed more than $500,000 in unpaid entitlements, including $309,689 in unpaid superannuation. As Sneakerboy’s woes hit the media, it was discovered that Luxury Retail No.1, one of the four entities related to Sneakerboy that ran Australian stores for the British luxury brand Mulberry, was also entering receivership, owing staff over $400,000 in super payments.

According to Jason Harris, a professor of corporate law at The University of Sydney, “this could be a case of running businesses by deliberately underpaying superannuation. But also, tax and super entitlements are complicated – it could also be a case of ineptitude by management rather than deliberate non- compliance.” Dixon’s report noted that Mair believed the company’s financial difficulties arose as a result of the pandemic. “Whilst I agree with the directors that the Covid-19 pandemic significantly contributed to the financial difficulties of the company, I am also of the opinion that the company became insolvent due to the poor strategic management, deficiency of working capital and poor financial control of the Sneakerboy Group,” he wrote.

Having departed the business more than a year earlier, Gray also wondered whether Sneakerboy was floundering well before the pandemic arrived. “I don’t think it changed it – it was happening already,” he says. “It maybe just accelerated it a little bit.”

If the administrator’s report indicated catastrophe, the liquidator’s report confirmed it. Dixon deemed that Sneakerboy may have been trading while insolvent from at least the middle of 2020; it was identified that unfair preference payments (transactions that discriminate in favour of one creditor at the expense of other creditors), uncommercial transactions (a transaction at a time when the company is insolvent which has no benefit to and/or is detrimental to the company, benefits a third party) and unreasonable director-related transactions (when a company enters into a transaction that unreasonably benefits a director or someone closely associated with them) were identified as possible recovery actions for creditors, but required further investigation. I called Dixon’s office a total of seven times seeking an update on his investigations, but my call was not returned.

All up, the company was dealing with $17.2 million in creditor claims. According to the liquidator’s report, it is unlikely that any creditors – employees included – will ever be fully reimbursed. While under the federal government’s Fair Entitlements Guarantee (FEG) scheme, employees of a liquidated company may be eligible for payment of their outstanding employee entitlements – wages, annual leave, long-service leave – crucially, the scheme doesn’t pay out superannuation.

For those who built Sneakerboy, learning the extent of the crash was a specific kind of crushing.

“Oh, it was painful,” says Shchelkunov.

Adds Anne-Laure Cavigneaux: “It’s just very sad. It was a heartbreaking moment. We saw it degrading slowly and surely.”

And Obeid: “Watching it turn into a luxury brand with large shopping centre stores was dismaying, not only because it was my baby, but also because I had real doubts about whether the new strategy could work.”

Reports filed with the Australian Financial Security Authority show that, in October 2023, Nelson Mair entered into a personal insolvency agreement (PIA) under Part X of the Bankruptcy Act. According to the AFSA, a PIA is a flexible way for a debtor to come to an agreement, settling debts without becoming bankrupt. Until the terms of the agreement are satisfied, Mair is prevented from managing a corporation, except with the leave of the court. When those terms are satisfied, he will be free to run a company once again. Currently, no insolvency records for Poulakis are recorded with the AFSA.

Meanwhile, Victorian County Court records show that Bizcap AU Pty Ltd – the financier Sneakerboy owed $919,583 at the time the administrator was appointed in July 2022 – has taken Sneakerboy’s former group financial controller Jayantha Hewamanna, Nelson Mair and Theo Poulakis to court. In February, the trial date was vacated and reset for 16 October, for a judge-only trial estimated to go for four days.

For personal reasons, Kyvetos wasn’t in a position to be interviewed for this story. As the face of Sneakerboy, many assumed he was present during its undoing. After emailing him over a period of months, he tells me he “lost all material influence on the operations of the business” when it was put into voluntary administration in 2015. In 2017, he relocated to Europe, where he worked as the creative director of Stylebop.com, before moving to luxury German e-commerce retailer Mytheresa, where he became the VP of menswear in 2018. He says he remained “concerned” with Sneakerboy, helping out where he could.

He shared the following statement on his time at the business: “There were some amazing people involved and they have all gone on to make marks around the world. I still keep in touch with many of them and they still share the same sentiment that something special happened there between 2013 and 2015. It shaped and inspired them and other brands around the world till today.”

Perhaps Sneakerboy’s ultimate legacy, then, is a valuable case study for young entrepreneurs.

Mair was sought for comment for this story but couldn’t be reached. His LinkedIn profile lists him as the founder of a company called Pure Retail, which launched in 2022. Pure Retail’s website is a holding page; a message I left in the contact widget was never responded to.

Today, Kyvetos is the founder and creative director of Athletics FTWR, a London-based sneaker brand that makes footwear for luxury French brand Kenzo, which is currently under the leadership of Japanese streetwear icon Nigo. Shchelkunov, meanwhile, is a fintech entrepreneur, while Cavigneaux and Eggleston have continued to design award- winning homes, community hubs and retail spaces. Nick Gray, who left Sneakerboy in 2018, went on to work at Westfield Australia for five years before moving into consulting; he was recently named one of the world’s Top Retail Experts by global insight firm RETHINK Retail.

When I meet with Gray for the final time, he puts into words what many of those I spoke to are feeling. “There just doesn’t seem to be any justice,” he sighs. “It’s such a shame.” But he still thinks fondly of Kyvetos, and the time he started working with the entrepreneur. As does Cavigneaux. “We had so much fun. The sky was the limit with Guy and Chris, and we really blew the glass ceiling.” The trouble with breaking glass ceilings? You create the opportunity for others to ride on your coattails, only for them to risk flying too close to the sun.

This story is published in the May/June 2024 issue of Esquire Australia. Find out where to buy it here.