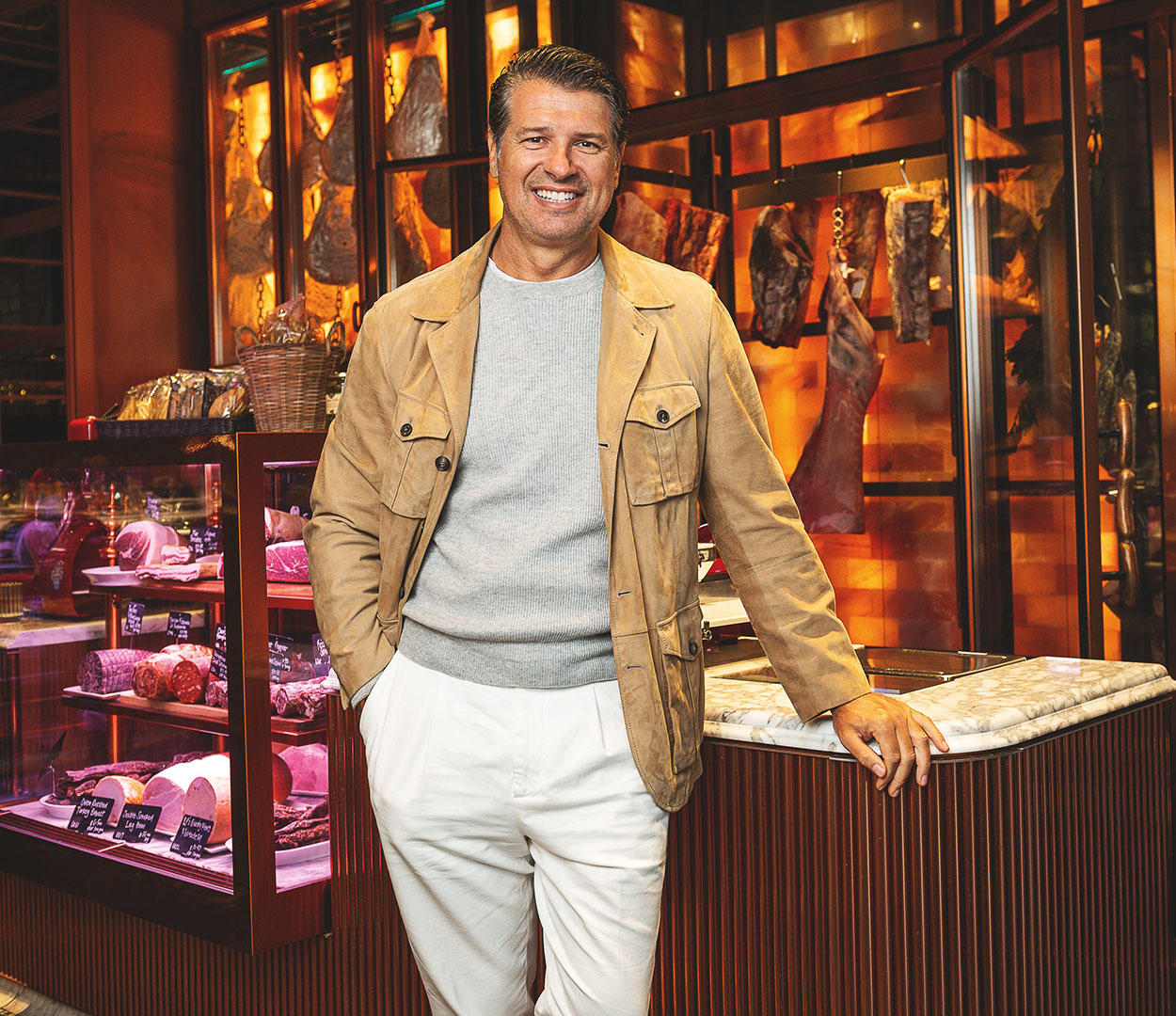

Meet Andrew Guard, the wine importer with the ‘unicorns’

For 20 years, he’s travelled the world in search of rare bottles, introducing ‘unicorns’ made by esoteric producers to local drinkers. As one of the most influential people in Australian wine, it’s no wonder they call him "The Guardfather"

IT’S RAINING OUTSIDE Sydney’s Bar Vincent the day I join Andrew Guard at his favourite table. A container of wine has just landed at his warehouse, and all eyes are fixed on a bottle it contained – a Chardonnay by pioneering Jura producers Emmanuel Houillon & Pierre Overnoy. Guard, wearing his trademark Cheshire grin, uncorks the enigmatic bottle as I and Louis Foillard – a close friend of Guard’s and member of the Foillard wine dynasty – watch on. In the wine world, these spellbinding bottles are known simply as ‘unicorns’: extremely rare, sought-after wines made by vignerons with mystic allure, who inspire fiercely loyal followings within the wine community.

What unfurls from the glass is a wild dance of quince, almond skin, white flowers, crushed stone and distant spices. The wine drinks like satin, leaving a profound impression that goes on and on.

As a tastemaker, Andrew Guard’s portfolio has shaped a new movement in Australian wine. Characterised by artisanal winemakers, his selection has guided us away from the heavy reds and tropical Sauv Blancs of yesteryear, and towards wines that are lighter and more expressive. In Australia, many of the most popular cult wines found on lists at the coolest bars and most prestigious restaurants – from France-Soir in Melbourne to Bar Copains in Sydney – are imported by Guard. Thierry Allemande, Alain Labet, Jean-François Ganevat, Cécile Tremblay and François Rousset-Martin – he’s single handedly responsible for bringing each of these labels Down Under, which is why hashtags like #InGuardWeTrust and #Guardfather often accompany pictures of unicorn bottles on Instagram.

And Guard’s impact doesn’t stop there. Among the crew of bon vivants I’ve learned from and shared bottles with – Andy Ainsworth of Dayelsford’s renowned Bar Merenda and Jeremy Shiell of central Victorian producer Saeke Wines – many have worked either for or with Andrew Guard. Like all true gurus, he can connect those in his orbit on an aesthetic pane, somewhere along the intersection of taste, history and agriculture, where industry lore, secrets and rare bottles go hand in hand.

His wine journey began in 1993, when he enrolled in Sydney hospitality management university The Hotel School. It was a time of opulence and theatrics in restaurants, the scene untouched by the financial caution that would follow in later decades. No restaurant embodied this spirit better than The Treasury, run by famed Australian restaurateur Tony Bilson. “It was this grand, fine dining room – all marble, gold leaf and contemporary art, no expense spared,” recalls Guard, who joined Bilson’s team as a sommelier in 1993. “They’d spend thousands on flowers each week. It was a different era – food costs weren’t even a concern.”

Bilson had a profound impact on Guard. He wasn’t just building a temple of fine dining – he was uniting its sacred and profane halves: food and wine. “Tony was one of those rare chefs who loved wine. Back then, the kitchen and front of house were separate worlds, and sommeliers were almost mythical creatures. But Tony would bring us together to taste and understand how food and wine could sing together.”

The education didn’t end in the dining room. On Sundays, it slipped into something looser and less formal, but perhaps more profound. “Every Sunday, a few of us from the restaurant would eat together at Lavender Blue Cafe [McMahon’s Point]. On Saturdays, my mate and I would scour Sydney’s bottle shops looking for interesting bottles to bring.” There was no curriculum. No sommelier school. No PDFs or podcasts. Just bottles, passed from hand to hand. “That’s when wine got under my skin – it became a collective passion,” recalls Guard. “We’d bounce off each other, learn the vocabulary, the dialogue of wine. [It was] just trade tastings, peer learning and raw curiosity.”

Then came the day Bilson offered Guard a kind of sacrament. “One day, Tony invited us all to his house. Midway through lunch, he took me introduced him to the art of importing. He also started reading more deeply, digging into wine stories that weren’t just about prestige, but about people, place and purity. “Reading The Wild Bunch by Patrick Matthews blew my mind. It focused on wines of character from small, family-run producers – fragile, artisanal, environmentally conscious. And it made me realise how little of that was available in Australia. I wanted in.” Then came Adventures on the Wine Route by iconic American wine importer and author Kermit Lynch. “Same story. I kept all this to myself. Never told anyone. But I knew this was the kind of wine I wanted to bring to Australia.”

Guard officially launched his business in 2006. He and his wife had saved a deposit for a house, but after a few failed applications, she suggested they do something different with the money. “My wife, who is now my ex, she said: ‘Why don’t we use the money to start that crazy wine business you keep talking about?’ I promised her, if we did this, I’d make it work, and we’d buy a house through the business. Eventually, we did.”

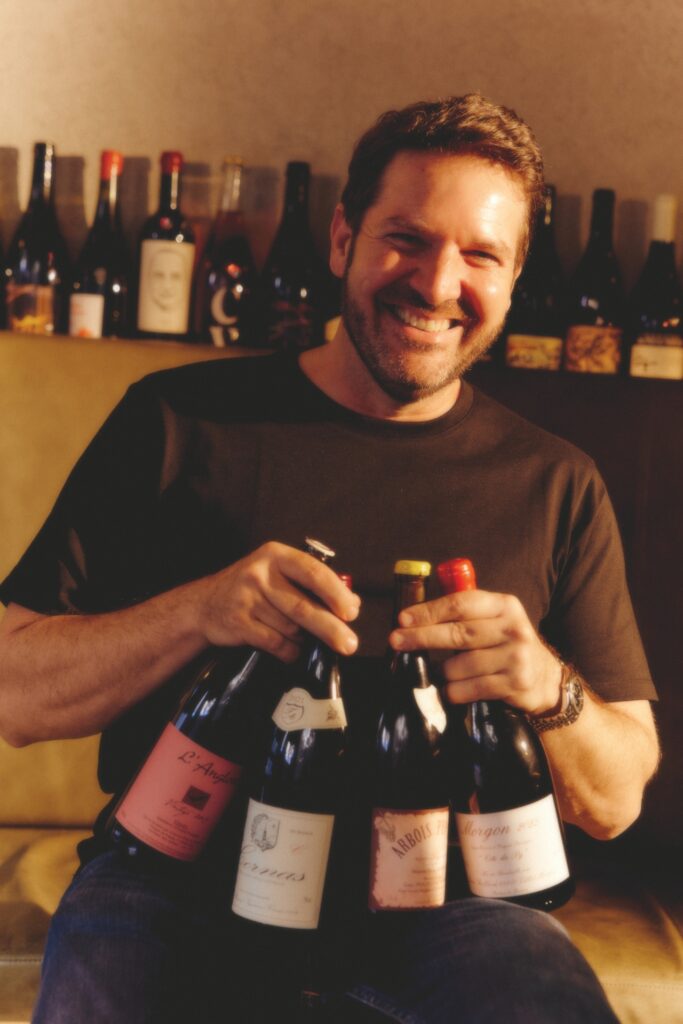

The first winemaker Guard reached out to was France’s Jean Foillard, the father of Louis Foillard, whom we shared the Houillon-Overnoy Chardonnay with on that rainy day at Bar Vincent. A natural wine icon whose Gamays helped reframe the Beaujolais region from supermarket to sacred tier, Foillard’s cosign gave Guard credibility. “I was nervous when I visited him, but he said yes. His wines had everything I believed in – purity, consistency, elegance,” he recalls. “We couldn’t afford a full container – I spent $65,000 and it was half empty. But I had Foillard’s wines, and that mattered.”

Next to Jean Foillard in that first shipping container were French labels synonymous with the rare bottles Guard is known for trading in today. “Eric Pfifferling of L’Anglore, Thierry Puzelat of Clos du Tue-Boeuf, and Philippe Pacalet, who used to be the winemaker for Henri- Frédéric Roch and the co-director of Domaine de la Romanée-Conti – legends,” he says. “They gave me a chance. Those wines were the bedrock of my company. I still work with many of them today. They shaped how Australians drink, especially with lighter, lower-alcohol wines, which really suit our lifestyle.”

Thierry Allemand, the French grower who’s spoken of like a prophet, also sold wines to Guard early on. “Allemand is a sage. He completely redefined quality in Cornas,” he says, referring to the tiny appellation in the Rhône valley. Among his restaurant clientele, Allemand’s Syrah is one of Guard’s most popular reds. “The floral, feminine perfume is aligned to its dark, meaty core . . . He can also make wine without sulfur. A lot of people say they can, but they can’t. And those Sans Soufre cuvées?” he adds, referring to the wines without sulfur . . . “They’re even better and even more stable than the ones with a tiny bit of sulfur.

“Tasting with him is a sensory tornado. His cellar is like a calling card of all the greatest wineries in France. You can drink anything you want when you’re down there with him – as long as it’s not his last bottle,” says Guard with a wink.

And then, there was Jura – or, rather, Pierre Overnoy and Emmanuel Houillon, the former known as the pope of natural wine. “The first time I saw the label was in a bottle shop in Japan, in 1993. It had a rusty colour with a pomegranate pink hue. I couldn’t work out what it was. Red? White? The more I dug, the more I learned. He was the first in France to go no sulfur, in 1986. He works only three hectares. He produces exquisite wine. I just thought, I have to meet this guy.” It wasn’t long before the pilgrimage was made. “I met Pierre and Emmanuel in 2009. Their famous little tasting room – there’s an old fax machine that doesn’t work, laundry drying in the corner, and you’re drinking €2000 Vin Jaune right next to it. It’s like going back 50 years.

“I always take notes during tastings like that. Because when I get back to Australia, I have to build the story of these wines – to get people to believe in them. And with the Jura, I really think that I was one of the first to bring it in big. They only make 20,000 bottles a year. That’s 1600 cases – for the entire world. They get solicited for wine every single day, but they’re old school. They sell a bottle to me for €25, and they see it listed on wine lists or auctions for $800. That side of the business – they find it gross,” he says. “It’s not business – it’s trust, friendship.”

In case you can’t already tell, Guard could talk about wine for days on end. He lives, breathes and drinks the very best of it, and in a world that’s increasingly driven by algorithms, acquisitions and fast-moving consumer goods, Andrew Guard remains a reminder that wine – real wine, the kind that withstands time – is still profoundly personal. His career hasn’t been built on market trends or flashy branding, but on instinct, loyalty and the conviction that great wine expresses character, not commerce. As Patrick Matthews writes in The Wild Bunch – that book that first blew Guard’s mind – “the most interesting wines are not made by the biggest, the richest or the most famous growers. They are made by the most committed.”

Guard may not be the one making the wine, but he’s one of the most influential players in the game. And he’s committed to the growers, to the land and to the drinkers who still believe a bottle can contain more than fermented juice. Just like the mythical creature it’s named after, a unicorn can offer up entirely new ways of seeing the world.

Bucket list: Andrew Guard’s four favourite cult wines from France

2014 Arbois-Pupillin Savagnin, Houillonovernoy

Wines of legend, they are released only when vigneron Emmanuel Houillon considers them ready to drink, meaning there are no set rules for how long a wine should be aged in cask or bottle – just regular tastings and pure intuition.

2019 Tavel Vintage, L’Anglore

Made by Eric Pfifferling and his sons, L’Anglore’s teasing, tantalising and intricate wines grace all the best wine lists in France. The 2019 is the best (and rarest) portion of the Tavel Vintage, aged in foudre (large wooden vats) and demi-muid (600-litre fermenting barrels) for two years.

2020 Cornas Chaillot, Thierry Allemand

Stunningly expressive wines of soaring aromatic complexity and perfect balance. With a tiny average production of 500 cases, there is never enough Allemand wine to satisfy demand. The closest thing to a cult winemaker the Northern Rhône region has seen.

2021 Morgan Côte du Py, Jean Foillard

One of the iconic wines of contemporary France, the Morgon Côte du Py is as pure and captivating as Beaujolais gets. Foillard captures the wild cherry, mineral and floraltinged quality of his vineyard in an unparalleled way, leaving the wine with haunting persistence and fragrance.

This story appears in the Winter 2025 issue of Esquire Australia, on sale now. Find out where to buy the issue here.

Related: