EDDIE MURPHY WAS a trailblazing comedian – as the man himself is happy to point out. But nowadays, it seems like the former king of stand-up comedy might be chasing his own tail, or his trail, as the case may be. At least that’s the conclusion you might reach after watching Murphy’s new Netflix doco, Being Eddie, the latest instalment in the star’s US$70m deal with the streamer.

Murphy, by many people’s estimation, including his peers, is in the conversation for the greatest comedian of all time. He’s certainly revered by his contemporaries and those that followed in his considerable wake, many of whom feature in this indulgent but nonetheless compelling hagiography – Jerry Seinfeld, Chris Rock, Tracy Morgan, and perhaps the man with the greatest claim to Murphy’s crown, Dave Chappelle.

For anyone who grew up in the 1980s, as I did, when Murphy’s comedic comet blazed incandescently bright across Tinseltown, he remains the high watermark for a bold, ribald brand of comedy that’s oft been emulated, never bettered.

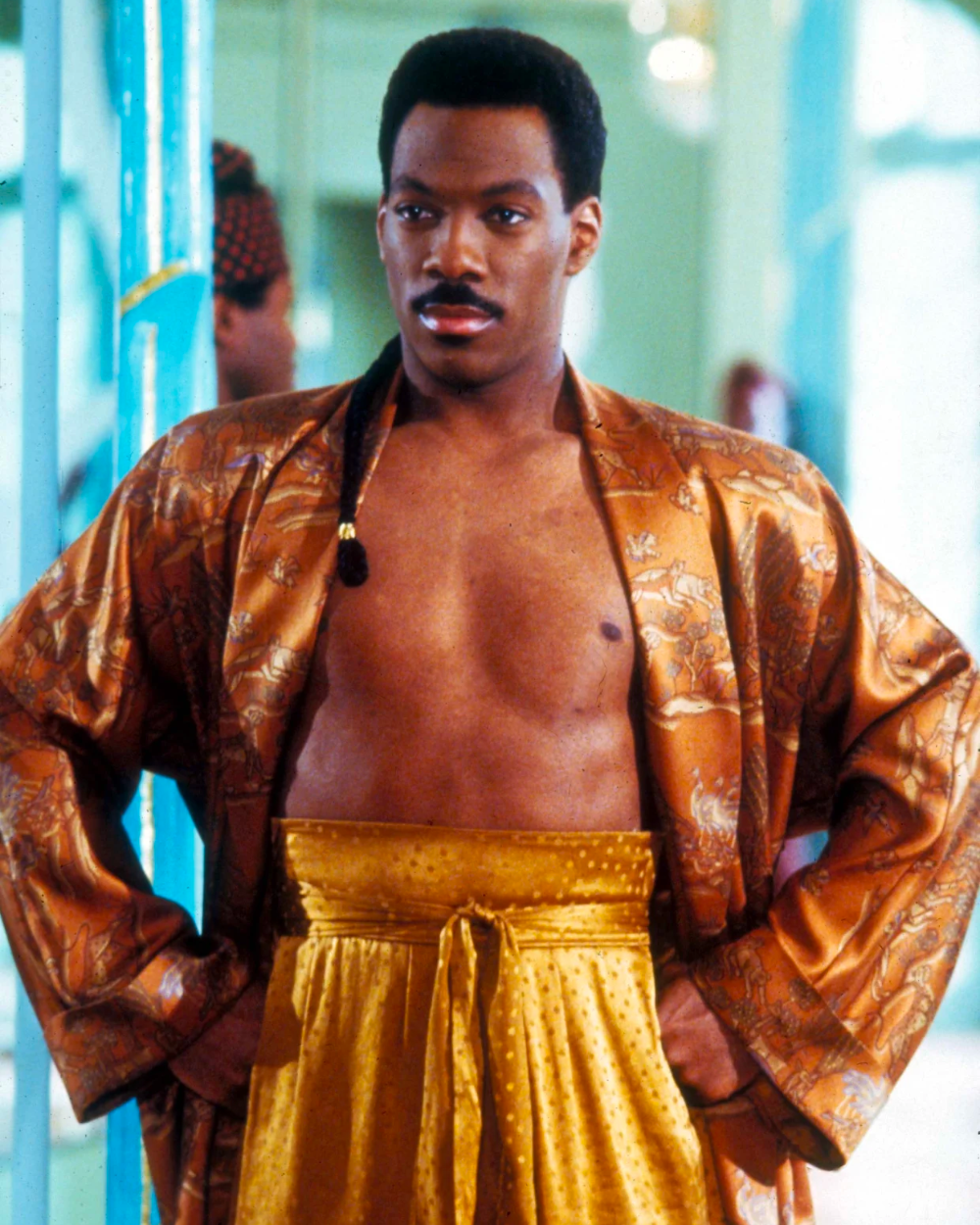

Beginning with his haloed stint on SNL in 1980, Murphy proceeded to unleash a string of box-office hits – 48 Hours, Trading Places and Beverly Hills Cop, among them – the latter marking the first time an African-American star had grossed over US$25m at the box office. It was followed by the silliness of The Golden Child and the incomparable Coming to America, possibly the star’s crowning achievement.

As his Hollywood career reached unprecedented heights, Murphy branched out, recording the pop confection Party All the Time with Rick James, while his stand-up specials, Delirious and Raw, became VHS monuments, possibly among the most quoted films on school playgrounds throughout the ’80s, ’90s and beyond – Pete Davidson recalls discovering Delirious in the early 2000s and watching it on repeat.

Murphy’s ’80s run is a feat unlikely to be matched and if he’d stopped there – or died young (more on that theme later) – his immortality would be assured. The early ’90s were less kind to the comedian, though Boomerang remains an underrated gem and landmark showcase for Black actors.

But after Vampire in Brooklyn in 1995, Murphy appeared ‘cooked’, with even his former comic alma mater, Saturday Night Live, laying the boot in, with a now infamous sketch by comedian by David Spade deriding Murphy’s fall. The star was stung by the barb and didn’t forgive the show’s creators for decades, eventually making peace with a triumphant hosting return in 2019, in which fellow legends in the Black comic firmament – Rock, Morgan and Chappelle – all showed up to give him his flowers.

The success of that show led to the aforementioned Netflix deal and Murphy’s subsequently mixed output – Dolomite and You People, as well as legacy sequels to Coming to America and Beverly Hills Cop.

It’s been a hell of a career and as Chappelle sagely observes in the doco, “The biggest success in show business, first and foremost, is surviving this s**t”. Later he adds, “surviving being Eddie Murphy is a hell of an accomplishment”. It certainly is but Murphy has paid a price along the way.

By all rights the star should have been swallowed up by fame and its attendant vices, as his fellow entertainment gods of the ’80s – Michael Jackson, Prince and Whitney Houston – all eventually were. As Murphy points out in the doco, he never did cocaine, drank alcohol or smoked. While fame is, er, famously, a drug in itself, at least part of its peril lies in the fact that for most mortals it requires pharmaceutical-abetted detachment to cope with both its intensity and the water slide into solipsism it invites. Murphy, to his credit, has preserved himself.

But Being Eddie is also notable for what’s been left out. There is no mention of the 1997 arrest of a trans prostitute who happened to be riding in his car during a traffic stop (Murphy maintained he was just being a “good Samaritan”). Similarly, his 14-day media-marriage to producer Tracey Edmonds and his initial rejection of the daughter he fathered with ex-Spice Girl Mel B are conspicuous in their absence. Everyone in Hollywood has skeletons, of course, but Murphy’s failure to acknowledge his is telling.

Perhaps the saddest part of Being Eddie concerns the comedian’s long estrangement from his first love: stand-up comedy. After Raw, stand-up ceased to be fun, Murphy says in the doc, the film’s towering success becoming a rod for his own back. Perhaps he knows he’ll never reach such heights again, because well, no one, not even Chappelle or Kevin Hart, have managed to do so.

It’s an impossible benchmark and Murphy seems conscious and cowed by his legacy, retreating into his gaudy gothic mansion with its retractable roof, where he’s reduced to recording voice notes of supposed comic gold, that he acknowledges will likely never see the light of day.

That is perhaps a generous reading of the predicament – if you can call living in a mansion with your 10 children who clearly adore you a predicament – Murphy finds himself in. A less kind interpretation is that the star is acutely aware that the times have irrevocably changed. His brand of profane, deliberately offensive comedy, much of it homophobic and racist, would get short thrift in the cancellation era – as Chappelle himself has found out. Of course, Murphy’s act always consisted of more than just callous F-bombs, as he pointed out in Raw, “Foreigners come up to me and be like, ‘Eddie Murphy, fuck you. Fuck you, Eddie’”.

What does an Eddie Murphy act look like without its sharp edges? My feeling is it would be largely toothless, with Murphy likely leaning into his God-given given talent for impressions. Indeed, he appears to hint as much in Being Eddie, where the filmmakers present him with two ventriloquist dolls in the form of his hero, Richard Pryor, and longtime punching bag, Bill Cosby. While that might be entertaining, hiding behind characters or exploiting others idiosyncrasies and weaknesses is not what his Gen-X fan base ultimately want, or likely to bolster his legacy.

But perhaps there is a way back, or forward, for the comedian, though it’s one that involves sinking his teeth into a subject he appears happy, for the most part, to avoid: himself. Instead of punching down from his Hollywood perch, Murphy could direct his acute powers of observation inward, dissect his foibles and fuck-ups, address those skeletons.

Yes, it would require exposing himself. To laugh at himself for once. But rather than the careful preservation of a larger-than-life comic persona that appears to be haunting him, he might find that by levelling his cold comic gaze upon himself he finds a way forward, and out, from under the weight of his mighty legacy. That would be brave. That would be raw.