Alex Russell’s ‘Lurker’ is ‘Misery’ for the social media era

I'm your number one fan

ALEX RUSSELL’S directorial debut Lurker opens with a deceptively simple encounter: pop star Oliver (Archie Madekwe) walks into a shop where he clicks with the retail worker Matty (Théodore Pellerin) over an obscure piece of music. Innocuous, but the quietly calculated moment becomes the seed for a relationship that builds into a tightly wound psychological thriller about access: who gets close to power, who wants it, and who mistakes proximity for intimacy.

The following hour-and-forty-minute run time is an intensely claustrophobic game of cat and mouse between the two leads. Their scenes oscillate between awkward warmth and low-grade hostility. The kind that builds when young men circle each other in social spaces governed by status and attention. Their conversations slip quickly from camaraderie into calculation, replicating the unstable emotional rhythms that define many male friendships: jockeying masked as loyalty, competitiveness couched as support.

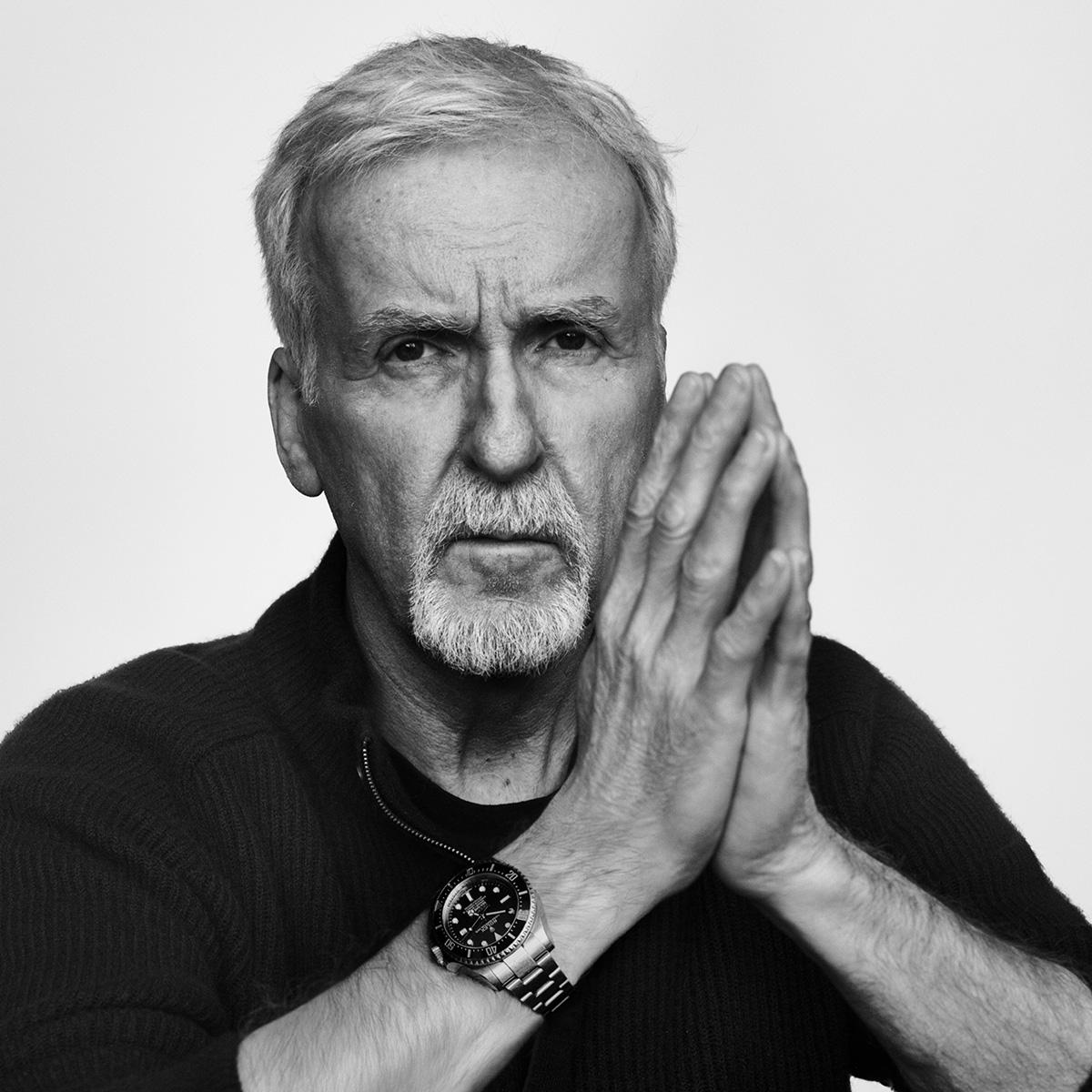

Russell, himself a former journalist before moving into writing for TV (Beef and The Bear) approached this dynamic from the perspective of a career observing the porous boundaries between admiration and aspiration.

“I think journalists in particular tend to really get this movie because they are always sort of towing that line of access and boundary between themselves and maybe someone they admire or someone they would like to get to know better,” he says. He points to Almost Famous as a reference point describing it as “this kid who gets to interview one of his favorite artists over the course of the film,” and asking whether “they still be friends after the piece is completed? And how that line tends to blur.”

Not quite the same question that lies at the core of Lurker, where it’s more about possession than platonic partnerships. But the slippery grey zone is there.

Within that liminal space of the film’s narrative, Matty and Oliver are never quite friends. A reality Madekwe and Pellerin acknowledge when asked why they thought Matty and Oliver kept coming back to each other.

“There’s definitely a transactional relationship there,” Madekwe says. “I dunno if it was friendship, but I think in the way that all so many relationships or friendships, especially in LA in this industry, tend to be built on a transaction of ‘You give me this, and I give you this’. And it’s kind of looked at under the guise of friendship.”

Pellerin is more direct: “I think the power dynamic is so clear that they can’t be friends. They’re both tools for one another.”

Yet transaction does not preclude genuine emotional belief, at least on Matty’s side. Pellerin describes moments where his character fully convinces himself that his intimacy with Oliver is real. “I think at some moments he really believes that he has real access to Oliver.”

From Oliver’s vantage point, the dynamic is far more performative. “He’s performing intimacy,” Madekwe says. “It is a performance of friendship because yeah, it’s not genuine.”

Layered beneath the celebrity dynamic is something even older: the hierarchies shaping male relationships more broadly. “Jealousy . . . especially among men, is one of the least confessed feelings of all because it’s so, so ugly,” Russell says. “And yet if you look at almost the entire world . . . so much of it is inspired by men being jealous of each other or being made to feel small.”

(If there is a sense that the film feels a little familiar, there is precedence. From the 1956 movie All About Eve, Stephen King’s iconic Misery to most recently The Idol all capture the slippery nature of fandom that so easily tips into something sinister. It’s also impossible to ignore the parallels to Emerald Fennell’s Saltburn, which Madekwe also starred in with a lead character called Oliver . . . )

To shape Oliver’s presence, Madekwe immersed himself in contemporary pop celebrity culture. “I was watching a lot of behind-the-scenes documentaries of a lot of contemporary musicians,” he explains. “Seeing the way that they would interact, the power dynamics, the way that they would speak to each other, the casual playfulness . . . that all of a sudden can switch into something more severe, like in the studio or before you’re about to go on stage.”

This leads to the biggest question of the film: What was Matty’s motivation, in the end? A question that’s asked within the film, and one I ask Pellerin during out interview.

“What is it that Matty wanted? I think it changes during the film,” he says. “I think at the beginning it is just about access to someone who he thinks is so high above everything else. Or to a kind of culture that he believes is at the height of life. Then he understands the mechanisms behind it and he’s like, well, I can play that game, too, and I can have the upper hand because I am more dedicated. So I think it changes in the movie. I think he goes through a sort of education of the world that he integrates.”

This shift, from yearning fan to the social climber, is where Lurker finds its deepest unease and speaks to the film’s broader cultural relevance: the contemporary crisis of parasociality.

Online culture has collapsed the distance between fame and fandom so entirely that emotional trespass becomes almost normalised. Platforms invite a sense of immediate connection. Posts, comments and DMs are dissolving the idea of boundaries altogether. What Russell dramatises is the consequence: when access feels limitless, entitlement follows.

Lurker is streaming now on Mubi.

Related: