The best books of 2024 (so far)

Our favourites are taking us to dazzling new frontiers.

It’s time to check in: How’s the year in books coming along for you, dear reader? Halfway through 2024, we’re enjoying an embarrassment of literary riches – and now we’re here to spread the gospel about our favourites.

The best books of the year (so far) are taking us to dazzling new frontiers. In the fiction landscape, a spate of new novels offers visions of humanity from unlikely narrators, including robots, aliens, and the undead. Meanwhile, it’s shaping up to be an outstanding year for memoirs; new outings from luminaries like Leslie Jamison, Sloane Crosley, and Lucy Sante will grab you by the heartstrings and refuse to let go. In the nonfiction space, some of our finest intellectuals have released titles that help us make sense of our changing world, from the culture-flattening force of algorithms to the future of work.

Here are the Best Books of 2024 (so far). Watch this space – we’ll continue adding to our list as the year progresses.

1

Consent, by Jill Ciment

At 17, Ciment began a sexual relationship with her drawing teacher, who was 47 and married with two teenage children. In 1996, she published a memoir of their unconventional marriage called Half a Life; now, nearly 30 years later, the widowed author throws a stick of dynamite at that book. In her new memoir, Consent, Ciment reconsiders her love story, disassembling the careful mythologies she’s constructed around her early years. In Half a Life, she insisted that she initiated the first kiss; looking back decades later in the pages of Consent, she remembers how her husband pulled her into a kiss when she hung back after class to ask a question about careers in the arts. “Does a kiss in one moment mean something else entirely five decades later?” Ciment writes. “Can a love that starts with such an asymmetrical balance of power ever right itself?” Unflinching and bravely told, this postmortem of a marriage is one of the gutsiest books of the #MeToo era.

2

The Stardust Grail, by Yume Kitasei

The Stardust Grail is set for release on October 29 in Australia.

Indiana Jones meets Star Wars meets Nietzsche in this thrilling galactic heist packed with existential thought. Kitasei’s nail-biting story centres on Maya Hoshimoto, once the galaxy’s most notorious art thief, who now lives a quiet life as an Ivy League archivist. When a dead explorer’s journal materialises at the archive – one that promises to lead her to “the grail,” an artefact with the power to open portals to other solar systems – Maya is forced out of retirement. But she isn’t the only one searching for the grail, and if it falls into the wrong hands, interstellar travel could become impossible. Maya’s quest across the stars is a space opera of the highest order, rich in breakneck pacing and memorable alien accomplices, but it’s in the quest for moral clarity that The Stardust Grail really soars. As Maya journeys from planet to planet, Kitasei offers a profound allegory about the dangers of colonisation, taking this rousing romp to the next dimension.

3

The Husbands, by Holly Gramazio

When 30-something Lauren returns to her London flat late at night, she finds her husband waiting at the door. There’s just one problem: When Lauren left the house, she was single. She quickly discovers that her attic is generating an endless supply of husbands; as soon as one goes up, another comes down, and her life re-forms around him. At first, Lauren wonders which husband she can live with for now as she seeks a suitable plus-one for an upcoming wedding; then, which husband she can live with forever; and ultimately, which version of her life and herself she can live with. In this warm, wise, and bittersweet debut, Gramazio delivers a moving meditation on the paradox of choice in modern dating (and modern life).

4

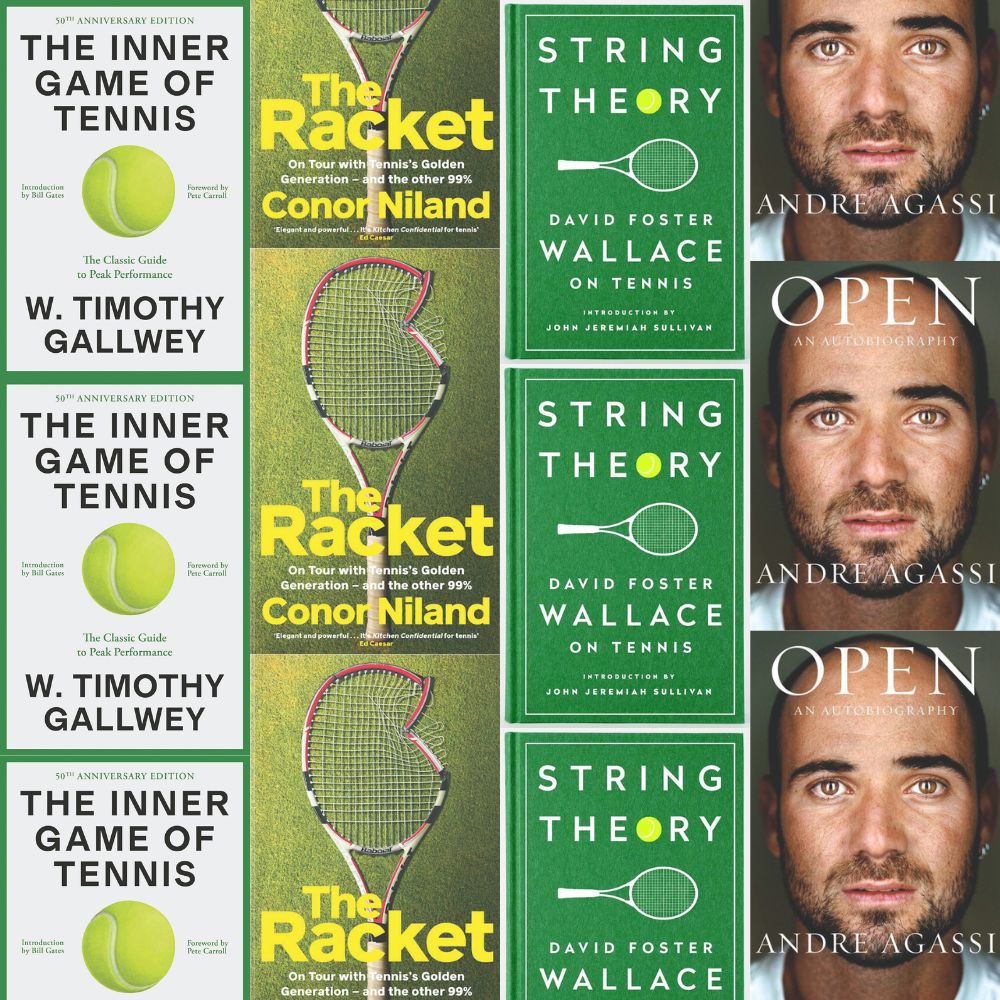

The Winner, by Teddy Wayne

The Winner is set for release on October 1 in Australia.

In Wayne’s latest novel, we see “the real winners of America” through the wide eyes of Conor O’Toole, a college athlete raised by working-class parents. Fresh out of law school, Conor decamps to coastal Massachusetts for a luxurious summer: In exchange for tennis lessons, he’ll receive free lodging on Cutter’s Neck, a gated oceanfront community for the grotesquely wealthy. But Conor has student loans to repay, so when a sharp-tongued divorcée offers to pay twice his hourly rate for more than just tennis lessons, he can’t help but acquiesce. Soon enough, he tumbles into an erotic affair that challenges everything he thought he understood about sex and power; meanwhile, he falls for a young writer. As Conor’s double life spins out of control, one horrifying mistake threatens to punish him for his trespasses among the elite. Gutsy and shocking, The Winner is a palm-sweating thrill ride through the lives of America’s winners and losers alike.

5

Code Dependent, by Madhumita Murgia

In a series of immersive reported vignettes, the Financial Times’s AI editor takes readers around the globe to investigate the technology’s damaging effects on “the global Precariat.” In Amsterdam, she highlights a predictive-policing program that stigmatises children as likely criminals; in Kenya, she spotlights data workers lifted out of brutal poverty but still vulnerable to corporate exploitation; in Pittsburgh, she interviews UberEats couriers fighting back against the black-box algorithms that cheat them out of already-meagre wages. Yet there are also bright spots, particularly a chapter set in rural Indian villages where under-resourced doctors use AI-assisted apps as diagnostic aids in their fight against tuberculosis. Fair-minded but unsparing, Code Dependent is the most lucid reporting yet on a fast-growing human-rights crisis.

6

Filterworld, by Kyle Chayka

Just how much do algorithms control our lives – and what can we do about it? In this eye-opening investigation, Chayka enumerates the insidious ways that algorithms have flattened our culture and circumscribed our lives, from our online echo chambers to the design of our coffee shops. But all is not lost: Chayka argues for a more conscientious consumption of culture, encouraging us to seek out trusted curators, challenging material, and spirited conversations. After reading Filterworld, you’ll be ready to start your “algorithmic cleanse” and get back in touch with your humanity.

7

Beautyland, by Marie-Helene Bertino

In 1977, Adina Giorno is born to a single mother in Philadelphia. Then, at age four, she’s “activated” by her extraterrestrial superiors 300,000 light years away on the dying planet Cricket Rice, who task her with reporting back about how humans think and behave. Through a fax machine in her bedroom, Adina transmits astute and often hilarious observations about the confounding behaviour of earthlings (for instance: “human beings don’t like when other humans seem happy”). Meanwhile, she experiences the bittersweetness of growing up; ostracised by the popular clique and mocked for her dark skin, she learns how, sometimes, being human means feeling alien. Warm, witty, and touching, Beautyland is an out-of-this-world exploration of loneliness and belonging.

8

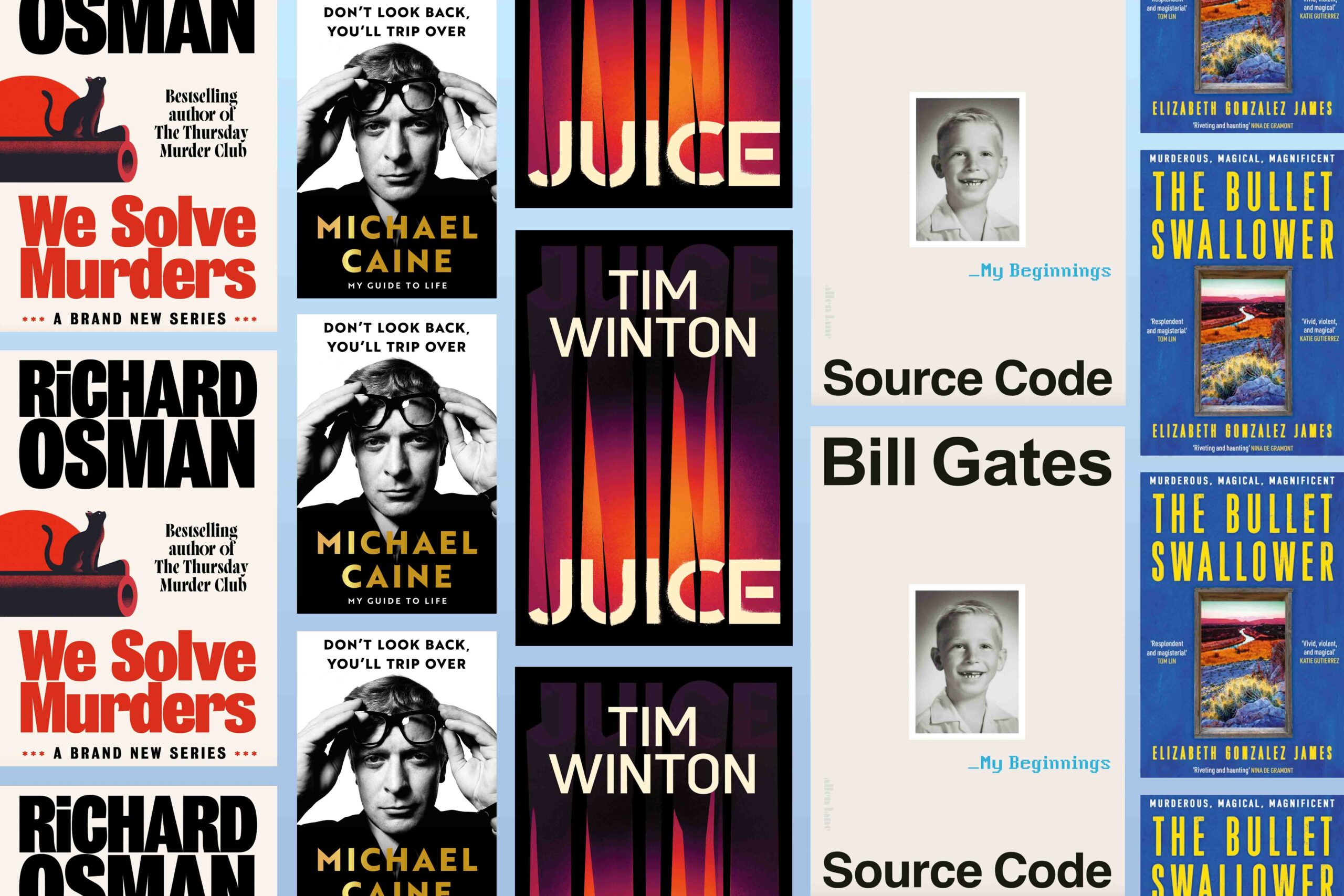

The Bullet Swallower, by Elizabeth Gonzalez James

Set in 1895 at the border between Texas and Mexico, The Bullet Swallower centres on Antonio Sonoro, the scion of a moneyed but deplorable family living in Dorado, Mexico. After a train robbery gone wrong outside of Houston, a shoot-out with the Texas Rangers leaves Antonio’s brother dead and Antonio horrifically disfigured, earning him the nickname “El Tragabalas” (the bullet swallower). Antonio’s quest for revenge against the Rangers takes him through the heart of the Texas badlands, where he weighs his violent impulses against the opportunity for repentance. Meanwhile, in a parallel narrative set in 1964, Antonio’s grandson Jaime, a Mexican movie star, transforms his grandfather’s story into a feature film, hoping to redeem the Sonoro name. Linking the two narratives is the mystical stranger Remedio, a reaper of souls guiding the Sonoros toward the light. Rich in lyrical language, gripping action, and enchanting magical realism, The Bullet Swallower augurs a bright future for the new frontier of westerns.

9

The Book of Love, by Kelly Link

One of our finest practitioners of the short-story form delivers her debut novel at last – and what a novel it is! The Book of Love is a phantasmagoric door stopper rich in characteristically Link-ian pleasures, like the collision of the mundane and the magical. In a coastal New England town called Lovesend, four teenagers investigate how three of them died, only to be resurrected by their music teacher (to whom there’s more than meets the eye). Then Lovesend is transformed by magical happenings as the veil between this life and the afterlife is ripped away, leaving our young heroes desperate to hang on to the real world. Enchanting and immersive, The Book of Love is a landmark achievement from a writer who never stops surprising us.

10

I Heard Her Call My Name, by Lucy Sante

In this candid and soulful memoir of gender transition, Sante recounts her experience of transitioning later in life at age 66. She describes an electrifying experiment with FaceApp’s “gender-swapping feature,” where the sight of her face (digitally altered to look more feminine) produced “one shock of recognition after another.” In one dimension of the memoir, Sante traces her realisation of her true self and her process of coming out; in another, she reconsiders her entire life through the prism of what she knows now. Sante’s account of meeting her true self is arresting, intimate, and a work in progress; as she writes, “Transitioning is not an event but a process, and it will occupy the rest of my life as I go on changing.”

11

This American Ex-Wife, by Lyz Lenz

In This American Ex-Wife, a blistering memoir-meets-manifesto about the fraught gender politics of marriage and divorce, Lenz details how the end of her marriage became the beginning of her life. Raised in a religious household and married at a young age, Lenz walked away from an unsatisfying partnership to rebuild her life on her own terms, only to discover that happiness, autonomy, and freedom lay on the other side. Weaving together a detailed history of marriage, sociological research, cultural commentary, and a frank dissection of her own personal experiences, Lenz paints a damning portrait of marriage in America: “an institution built on the fundamental inequality of women,” as she describes it. Yet the book is also a rousing and exuberant cry for a reckoning – one through which couples can love freely, leave freely, and build meaningful partnerships based on the full and equal humanity of men and women alike.

12

Working in the 21st Century, by Mark Larson

Fifty years after Studs Terkel’s Working, a historian delivers a comprehensive sequel for the age of late-stage capitalism. Assembled in a polyphonic oral history, Larson presents 101 conversations with American workers from all walks of life, including teachers, nurses, truck drivers, executives, dairy farmers, stay-at-home parents, wildland firefighters, funeral directors, and many more. In the wake of the pandemic and the Great Resignation, Larson’s subjects share their struggles to make ends meet, reckon with economic upheaval, and locate meaning and purpose in their work. Presented together in one thick volume, these often-fascinating anecdotes are a rich portrait of modern-day economic anxiety and social change.

13

Splinters, by Leslie Jamison

In her latest bravura memoir, Jamison chronicles a wrenching period of rupture and rebirth. When their daughter was 13 months old, Jamison and her husband separated; what followed was a brutal struggle to balance parenthood, work, dating, sobriety, and creative fulfilment, all while the pandemic loomed. Told in overlapping, ever-widening circles of thought, Splinters details Jamison’s struggle to inhabit the roles we ask of women: mother, daughter, lover, friend. At the same time, the book is an intimate tribute to the author’s rapturous love for her daughter. Splinters thrives in this messy, imperfect complexity – in “the difference between the story of love and the texture of living it, the story of motherhood and the texture of living it.” Honest, gutsy, and unflinching, Jamison scours herself clean here and finds exquisite, hard-won joy in the aftermath.

14

Harper Whiskey Tender, by Deborah Jackson Taffa

Born on the California Yuma reservation and raised in Navajo Territory in New Mexico, Taffa situates her outstanding debut memoir in similar collisions of culture, land, and tradition. Here she recalls the people and places that raised her – especially her parents, who pushed her to idealise the American dream and assimilate through education. Taffa layers in diligent research about her mixed-race, mixed-tribe heritage, highlighting little-known Native American history and the shattering injustices of colonial oppression. Together, the many strands of narrative coalesce to form a visceral story of family, survival, and belonging, flooding the field with cleansing light.

15

Grief Is for People, by Sloane Crosley

In 2019, Crosley suffered two keelhauling losses: First her apartment was burglarised and her jewellery stolen, then one month later her friend and mentor Russell Perrault took his own life. For Crosley, the two losses became braided together; “I am waiting for the things I love to come back to me, to tell me they were only joking,” she writes. In this raw and poignant memoir, divided into five sections that correspond to the five stages of grief, she links her frantic desire to recover the stolen jewellery with her inability to bring back Perrault. Leavened by Crosley’s characteristic gimlet wit, this excavation of grief, loss, and friendship leaves a lasting twinge.

16

Wandering Stars, by Tommy Orange

In this stirring sequel to his breakout novel, There, There, Orange tells two linked stories: One centres on a survivor of the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre, Jude Star, who’s taken to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School and forcibly stripped of his identity and culture. The other traces his modern-day descendants in Oakland, reeling after the powwow shooting that ended There, There. In this wrenching story about the legacy of colonial violence, we see generations of Native characters orphaned from their past. Through poignant resonances between then and now, Orange delivers an epic saga of generational trauma, devastating to behold and impossible to put down.

17

Great Expectations, by Vinson Cunningham

Cunningham’s sensitive and sophisticated roman à clef centres on David, a 20-something Black man working in a minor fundraising role on an upstart senator’s presidential campaign. The author, who worked in the Obama White House, is clearly writing about an Obama analogue (this eloquent Black senator “project[s] an intimacy that was more astral than real”), but connecting the dots between fact and fiction is the least interesting reading of Great Expectations. As a young father and a college dropout, David struggles to relate to the privileged world of political palm greasing. As the campaign burns toward the White House, Cunningham spins a wise coming-of-age tale about power, idealism, and disillusionment.

18

Mariner Books Annie Bot, by Sierra Greer

In this provocative debut novel, Greer delivers a Frankenstein for the digital age. Sexbot Annie is the perfect girlfriend for her wealthy human owner, Doug: Programmed to please, she cooks, cleans, and adjusts her libido to Doug’s whims. But Annie is an “autodidactic” robot, meaning that she’s always learning and changing. As she experiences jealousy, secrecy, and loneliness, she becomes less perfect to the loathsome Doug and ultimately flees to meet her maker – with dangerous results. Annie’s painful journey of becoming is a poignant parable for the age of AI; it’s a rich text about power, autonomy, and what happens when our creations outgrow us.

19

James, by Percival Everett

James centres on a seminal character from American literature – and yet, seen afresh through Everett’s revelatory gaze, it’s as if we’re meeting him for the first time. Blasted clean of Mark Twain’s characterisation from The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, the enslaved runaway Jim emerges here as a man of great dignity, altruism, and intelligence. The novel opens in Hannibal, Missouri, where Jim teaches enslaved children to run their speech through a “slave filter” of “correct incorrect grammar,” designed to pacify white people. Then the story settles into Twain’s familiar grooves – on the run together, Jim and Huck raft down the Mississippi River, facing danger, separation, and charlatans aplenty. Along the way, Jim imagines verbal sparring matches with dead philosophers, falls in love with reading, and begins to pen his own story; “with my pencil, I wrote myself into being,” he writes. And so he does: On the road to freeing himself and his family, Jim becomes more self-determined than ever. Clever, soulful, and full of righteous rage, his long-silenced voice resounds through this remarkable novel. Subversive and thrilling, James is destined to become a modern classic.

20

Who’s Afraid of Gender?, by Judith Butler

One of our foremost thinkers returns with an essential polemic on gender, an urgent front line of the culture wars. Butler argues that by turning gender into a “phantasmic scene,” conservative politicians have diverted political will from the most pressing problems of our time, like climate change, war, and capitalist exploitation. Butler explores how various movements around the world have weaponised gender to achieve their goals, with a particular focus on trans-exclusionary radical feminists (TERFs). Who’s Afraid of Gender? calls for gender expression to be recognised as a basic human right and for radical solidarity across our differences. With masterful analysis of where we’ve been and an inspiring vision for where we must go next, this book resounds like an impassioned depth charge.

This story originally appeared on Esquire US

Related: