BRIGHT BREWERY isn’t the first place you’d expect to find a large group of men having animated conversations about the novel they’ve just read. But at 7pm on the first Wednesday of every month, the shed-like brewhouse in country Victoria is packed with guys of all ages, each carrying a copy of the same book – recently, it was The Chase by next-gen Australian crime writer Candice Fox. Far from being a coincidence, everyone here is a member of the Bright chapter of Tough Guy Book Club. Many are avid readers; others have joined for the company and conversation. Here, disagreement is encouraged – no two people come away from a work of fiction with the same reading, after all. But there’s one thing most members agree on: the first Wednesday of every month is the social occasion they look forward to most.

The first meeting of Tough Guy Book Club took place in a Collingwood pub in 2012. The club was started by Shay Leighton, a lapsed reader of fiction who was looking to return to the hobby. “I started it because I got to a point in my life where I’d buggered lots of things up; I was quite lonely,” explains Leighton. “I was trying to look for things that used to work in my life that I’d let fall by the wayside. And reading was one of them.” He convinced a couple of mates to come along, and the rest, as they say, is history. Today, there are more than 100 ‘chapters’ of Tough Guy Book Club all over the world, from Tamworth in regional NSW to New York City. “It’s a hobby that got out of hand,” he chuckles. To Leighton, the success of the club is proof that men really do want to read novels.

In literary circles – and, more recently, the mainstream media – the belief that men don’t read fiction has become pervasive, to the point where you have to wonder whether we’ve spun it into a self-fulfilling prophecy. In 2021, it was reported by The Telegraph (UK), The Guardian and The Times Literary Supplement that in the US, UK and Canada, women accounted for about 80 per cent of all fiction sales. In Australia, the data is slightly less skewed: according to a 2022 pilot survey by Nielsen BookScan Australia, 42 per cent of reported adult-fiction book purchases were made by men, compared to the 58 per cent made by women. But there’s also a difference between buying and reading. Australia Reads’ most recent national survey shows that men make up only 16 per cent of ‘engaged readers’ in Australia. When speaking to a book-publisher friend who asked to remain anonymous, they confirmed that men – and young men, in particular – are a market that publishing houses have long “tried to crack”, but that “no one really knows how to do it in Australia”.

This trend appears to begin in the classroom. In 2022, being a school-aged boy was labelled “an educational risk factor” after NAPLAN results indicated that 20 per cent of boys don’t meet national minimum reading and writing standards. But it’s also embedded in the masculine ideals that Australia and many Western countries perpetuate.

“Somewhere along the way, it was decided that reading wasn’t tough, which is the reason why people laugh when I tell them the name of our book club,” observes Leighton, adding that he regularly hears new members say they haven’t read a book since high school – “and I’m talking 40-year-old guys, so that’s more than 20 years,” he adds. “But who on Earth invented the rule that reading wasn’t tough? And why do we continue to be our own jailers on this stuff?”

THIS IS NOT the first time Max Easton has been asked to talk about the reading habits of Australian men. The Australian author of The Magpie Wing, which was longlisted for the 2022 Miles Franklin Literary Award, and follow-up Paradise Estate (2023), which was highly commended at this year’s Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards, has appeared on a number of panels discussing what he paraphrases as “the crisis of men and fiction”. “It’s something I do resist a little bit, because I don’t think it’s a crisis, as such,” he reflects.

The Magpie Wing is a coming-of-age novel set in Sydney against backdrops that, while familiar to many, are rarely depicted in works of contemporary literary fiction: NRL fields, sweaty punk-music gigs, crumbling inner-west pubs ripe for demolition. It was Easton’s ambition to forefront his novel with “stereotypically male themes” that made his publisher Giramondo – which was described to me by a literary agent as “the A24 of Australian publishing” – take a chance on him. The payoff came slowly but surely (that same agent referred to The Magpie Wing as a “sleeper hit”). “I had quite a few emails from guys saying they’d never seen rugby league in a novel. And they also hadn’t seen punk music. There seemed to be a real recognition of the types of upbringings the male characters [in The Magpie Wing] had. A lot of men saw themselves in the book, and saw people they knew,” says Easton.

It’s not just the themes and settings that had men relating to Easton’s first book (he shares that Paradise Estate seems to have resonated more with female readers). “I do write about men, and I write about them in a way that’s not always critical,” he says. When I ask him to elaborate, he acknowledges a trend in contemporary fiction where “men in the book are kind of just there as a villain. It’s like an oafish working-class man as a foil for his partner, or he’s a married man having an affair with a younger woman. That’s a very common device in the last few years.

“Don’t get me wrong – I think those stories can be good,” he says. “But I think in the wake of #MeToo, it became more attractive to publish stories that were critical of men along those lines. And often, when the publishing industry latches onto something that’s topical, the market becomes flooded with it.”

Recommended reading:

Dusk, by Robbie Arnott

Each of Arnott’s novels is underpinned by environmental concerns, but the worlds he conjures are far from dystopian. Part thriller, part magical realism, Dusk transports us to a tempestuous wilderness, where a puma roams free – for now. If you feel like disappearing into another world, this is the book for you.

Pan Macmillan; $35.

Big Time, by Jordan Prosser

Self-described as “Australia’s explosive and totally punk breakout novel of 2024”, Big Time follows a designer drug- addicted bass player and his band on tour in a future where pop music is propaganda and science can’t be trusted. If you like fast-paced reads, you’ll inhale this in one sitting.

University of Queensland Press, $35.

It’s true: bestseller lists and prizes for fiction have been dominated by female authors in the last few years, and among young women especially, reading has never been cooler – even model, It girl (and daughter of Cindy Crawford) Kaia Gerber has her own book club with a huge following of Gen-Z women who carry their books like status symbols. Easton wonders whether the ‘men-don’t-read- fiction’ debate is “a funny conservative reaction to a long- overdue increase in diversity in the publishing world” – after all, it wasn’t that long ago that men like Martin Amis, Salman Rushdie, Irvine Welsh, Jonathan Franzen and David Foster Wallace sat at the top of those bestseller lists.

At a writers’ festival recently, Easton recalls being asked by a woman in the audience if it was hard for him to be a male writer. “I couldn’t believe it. I mean, it’s obviously very easy to be a man in a patriarchal society,” he says with a self-aware laugh. “But for whatever reason, this pervasive myth that men aren’t interested in novels exists.”

He refers to the emails he received after the publication of The Magpie Wing as proof it isn’t that black and white; not only do men read, but they want to discuss what they’ve read. “That kind of connection between me and a reader, or a group of readers – that’s been the best part. Because it’s an increasingly lonely world and being able to connect through books is really important to me.”

LONELINESS IS WHAT led Leighton to launching Tough Guy Book Club, and it’s also the reason many men seek out the group. A 2023 survey by men’s health organisation Healthy Male found that 43 per cent of Australian men were lonely, with middle-aged men aged between 35-49 reporting the highest levels of loneliness. The average age of Tough Guy Book Club members is 44, but in some chapters, you’ll find twentysomethings sitting next to 80-year-olds. “Intergenerational conversations are really important to our club,” says Leighton. “The wonderful thing about fiction is that your interpretation of the books changes as you get older. Like, you read The Old Man and the Sea at 16, and you read it again at 40, and again at 70, and [each time] you’ll get something very different out of it.”

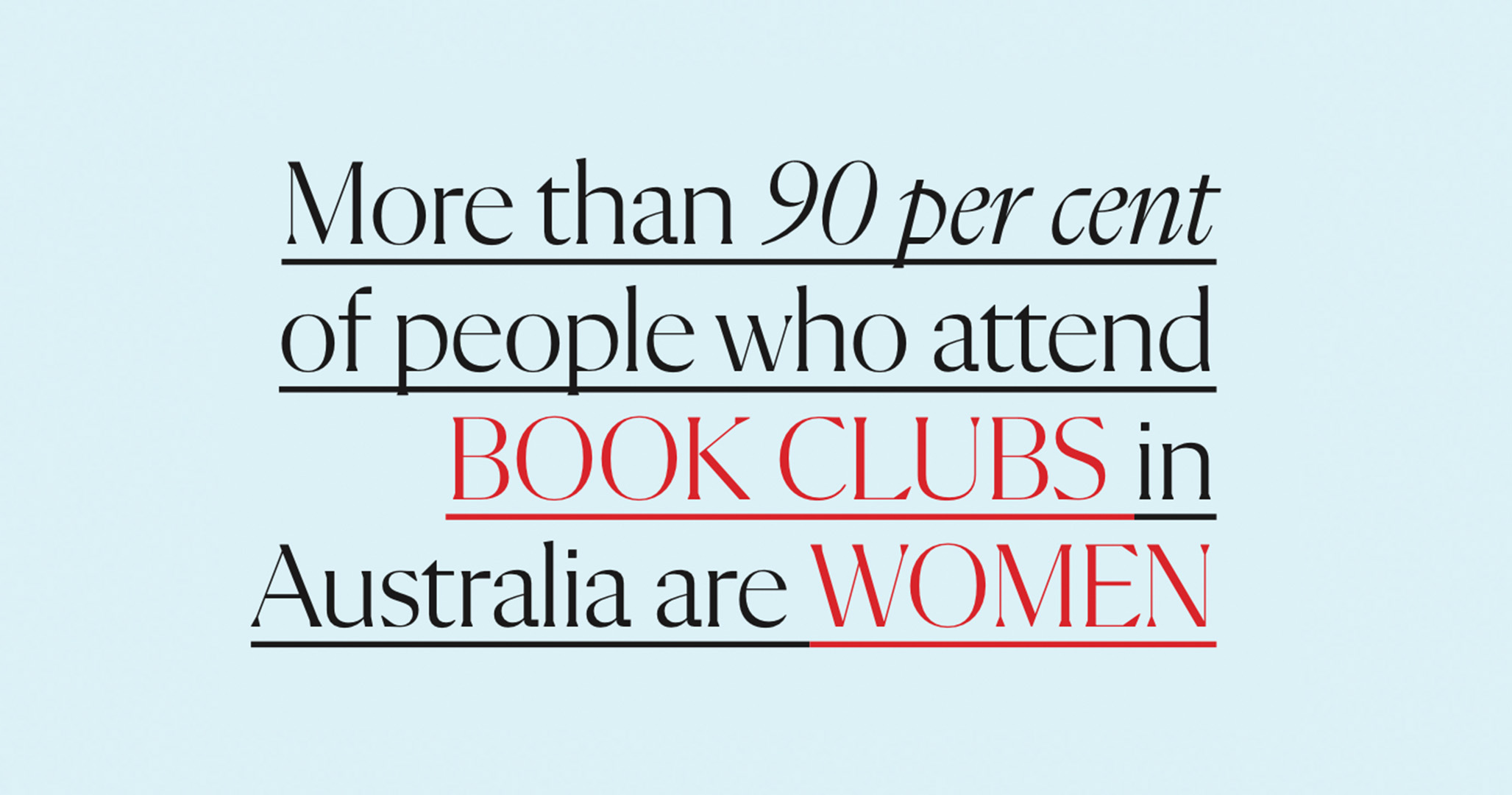

Those statistics on male loneliness don’t surprise Leighton, nor does it surprise him that joining a book club is an appealing salve. “You’ll find a lot of men want to meet new people, and a lot of men want to read more. If you Google those two things, you’ll probably get ‘join a book club’.” Still, the men who take Google’s advice appear to be in the minority: according to Australia Reads, more than 90 per cent of people who attend book clubs in Australia are women. And in recent years, the cultural impact of book clubs run by famous women – Kaia Gerber’s Library Science, Reese Witherspoon’s Reese’s Book Club and, of course, the institution run by Oprah – has been phenomenal; a bookseller I spoke to confirmed their bestseller lists are often dictated by the book-of-the-month picks from these clubs. Save for Obama’s annual reading list, I could find no book clubs run by male celebrities with a similar reach.

Tough Guy Book Club’s ‘About Us’ page specifies that it’s a men-only organisation. “But let’s be very clear about this, we’re not in any way anti-women,” says Leighton. “We just think that men having a chance to read more and talk more about stuff is a good idea.”

Recommended reading:

An Exciting and Vivid Inner Life, by Paul Dalla Rosa

Not a short-story person? Dalla Rosa’s collection, which meets 10 protagonists at particularly awkward points in their lives, may convert you. His sense of irony is dazzling yet, ultimately, these tales will leave you feeling tenderhearted. A stylish reminder that beauty can be found in the ugliest of circumstances.

Allen & Unwin; $33.

Born Into This, by Adam Thompson

In this cracking collection of short stories, proud Pakana man Adam Thompson tackles themes of racism, identity politics and navigating our way through a changing climate with impressive pathos. His forthcoming debut novel promises to be similarly incisive.

University of Queensland Press; $33.

All of Tough Guy Book Club’s meet-ups are held in pubs, and this isn’t because its members drink like Hemingway used to – some don’t drink at all. The setting has more to do with the importance of meeting in ‘third spaces’ – surroundings that aren’t your home or workplace. “How men relate to their community has changed quite radically in a short amount of time,” Leighton points out. “If you’re middle- aged, your grandfather was probably a member of four to five civic organisations: the Church, Rotary Club, the Buffalo Club, local football club, volunteer fire service . . . And then within two generations – again, if you’re middle aged, statistically you’re probably a member of none of those things.” With no members, these communal spaces cease to exist.

“I think these spaces are really important for men’s communities,” says Leighton. “And pubs play an important part in how we relate to each other. If you knock all the pubs down to build apartment buildings, you’ve got a lot of people with not a lot of space to hang out beyond home or work.”

It’s worth mentioning that work-chat is strictly off limits at Tough Guy Book Club – Leighton specifically asked that I not mention his day job for this reason. “It’s so you’re not just introducing yourself as what you do for work; you’re introducing yourself as a person. Men are great at being a collection of responsibilities – a husband, a father, a person that works in marketing – as opposed to people,” he explains. “We’ve got a really broad socioeconomic demographic [at the book club], and no one knows what anyone does for a living. You’d be surprised how much small talk it cuts out.”

Without the small talk, members can dive straight into conversation about characterisation, plot and how they relate to the story on a personal level. The club’s reading list is made up exclusively of fiction, because, according to Leighton, “guys read enough cricketer autobiographies and books about World War II”.

“We don’t read good books. We read interesting books – books that are interesting to talk about. Because books are social in nature, not individual. And people are social creatures. In my opinion, this whole ‘lone-wolf’ nonsense has really ruined some people’s ideas about this.”

Recommended reading:

No Church in the Wild, by Murray Middleton

Set between a Melbourne housing commission tower and the Kokoda Trail, with the sharpness of a Watch the Throne-era Kanye track, Middleton’s novel follows a wannabe rapper and his two best friends as they forge their sense of self in a prejudiced Australia. If you like your fiction gritty, you won’t find a book sharper than this.

Pan Macmillan; $34.

Why Do Horses Run? By Cameron Stewart

When a debut novel has been endorsed by Tim Winton, you know it’s worth reading. Built around a reclusive man who’s lost in more ways than one, the protagonist of Why Horses Run is not so much finding himself, as he is making a moving attempt to do so. Perfect for those feeling similarly adrift.

Allen & Unwin; $33.

WHILE THIS STORY is about men and fiction, the popularity of non-fiction among guys must be acknowledged. It would be easy to generalise here or lean on anecdotal evidence – as one commenter on a 2021 UK The Telegraph story titled ‘The real reasons why men don’t read books anymore’ noted, “I don’t read fiction for the same reason I don’t watch movies. They are not real”.

But that same 2022 pilot survey by Nielsen BookScan Australia revealed that 44 per cent of all book purchases were made by men (compared to 42 per cent fiction). Over the last decade, we’ve also witnessed the rise of a certain strain of self-help books – those that promise enhanced productivity and self-optimisation.

Atomic Habits (2018) by James Clear has spent a whopping 243 weeks on The New York Times Best Seller list, while our hustle-obsessed culture has created the perfect climate for titles like Can’t Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds, by former US Navy Seal David Goggins, to thrive.

This doesn’t surprise Steven Roberts, a professor of education and social justice at Monash University, whose work focuses on youth and critical studies of men and masculinities. “This sense of self-optimisation is the back end of 45 years or more of increased emphasis on the individual being the architect of their own destiny,” he observes, adding that the shift is being driven by “traditional ideas of gender and masculinity that emphasise success, strength and self-reliance for men . . . Competitiveness and autonomy are conventions of masculinity, and the idea that men are driven to improve themselves to gain an edge in personal and professional pursuits seems to reflect that.”

Meanwhile, in addition to writing books about their successes, some of the wealthiest businessmen in the world – Elon Musk, Bill Gates, Warren Buffet – espouse the benefits of reading, yet the books they recommend are almost exclusively non-fiction.

In 12 years of running Tough Guy Book Club, Leighton has observed that, before joining,

members who liked to read would gravitate towards advice books, because they felt like there was some utility to reading them; in our increasingly time-poor world, it felt like an activity they could justify. “I think guys can justify reading a book about factual things, or something about their work. They can find time for that because they think of it as un-frivolous. Whereas reading fiction doesn’t have such a clear-cut purpose or outcome. And that’s the point,” Leighton adds with a laugh. “It’s a hobby and it’s for yourself.”

Ironically, reading fiction does have very positive outcomes – they are just harder to quantify. A 2021 study by the Journal of Librarianship and Information Science found that by presenting ideas subtly and in more roundabout ways than nonfiction typically does, fiction fosters enhanced critical thinking, while the impact of reading fiction on our capacity for empathy has been widely touted by experts in the field, including Canadian professor of cognitive psychology Keith Oatley, whose vast body of work is dedicated to the subject.

Which brings us back to what author Max Easton refers to as the “pervasive myth”. “It’s well-known the publishing industry runs on accepted wisdom,” he says. When it comes to writing fiction that appeals to Australian men, the overarching attitude seems to be, ‘This thing is difficult, so don’t try’. “Even if only 500 people buy it, a niche audience is still an audience, right? Why not take a risk on the thing that’s tough to crack if you’re failing at the thing you’re supposed to be cracking?”

It’s not that men don’t – or don’t want to – read fiction. Sure, the statistics may show guys are less likely to join a book club or spend their days with their nose in a novel. But that doesn’t mean we should perpetuate this idea that we’re in a crisis. Of course, big cultural shifts like this don’t happen overnight. In the meantime, perhaps we need Brad Pitt to start a book club. I know plenty of men – and women – who would happily join that.

This story originally appeared in the September/October 2024 issue of Esquire Australia.

Find out where to buy the issue here.