In defence of middle-aged cliff-jumping (and what it taught me about mortality)

My friends and I jump off the same cliff every year. This year, for the first time, it felt like a death leap

Every summer my friends and I jump off the same cliff. It’s called Great Tor, a huge tombstone-shaped slab of rock that looms above a quiet beach on the South Wales coast. When we were teenagers, we leapt off it for fun, scream-laughing as we plunged into the waves. In our twenties we leapt off it together, hand in hand, as a statement about the permanence of our friendship. Then in our thirties — when that permanence was threatened by many of us moving out of Wales to live in different countries — we continued to meet up and leap off the same chunk of picturesque limestone because at least that was one thing that stayed the same.

I am now 43 — and last summer I noticed another change. We still all met at the same beach, but this was the first time that I really struggled to convince my friends to swim out with me at high tide and make the ascent. One of my oldest friends, Matt — a bearded, outdoorsy father of two who was recently given a chainsaw for his birthday — told me in very clear terms that it was a bad idea, irresponsible and unsafe, and that I should not go about pressuring anyone else into joining me on what was, at source, a desperate attempt to claw back the reckless freedoms of youth, a pathetic refusal to accept the realities of ageing. He may not have phrased it exactly like that. But basically he wanted me to grow up, and I might have done so, were it not for my friend Naomi deciding that she wanted to join me.

Together we swam out towards the rocks. The jump was really only viable at high tide. And it was true that, as we breaststroked slowly through the small waves, the tide was already on its way out. We could feel it tugging us out to sea. The Bristol Channel has a huge tidal variation, the second biggest in the world, and when the tide turns it moves quick, sucking itself away into the North Atlantic. When we got near the jump-spot, I did a depth test, letting myself sink to the bottom of the sea, skimming the sand with my toes. It was, by this highly imprecise calculation, still deep enough — at least for now.

As we peered down from the high ledge, the water looked dark and menacing

The steep rocks on which we climbed were carpeted with tiny molluscs that made it feel like walking on a box grater, specifically the side used for grating nutmeg or ginger. My right foot was bleeding by the time we got to the top, leaving a trail of little red splotches on the stones. I decided not to mention this to Naomi, not wanting to make things more ominous than they already were. As we peered down from the high ledge, the water that had seemed blissfully calm and clear when we were swimming in it now looked dark and menacing. It rose and fell like a great sea creature, breathing.

We took it in turns to stand at the precipice, adopt an action pose and then retreat back, saying no way no way no way. But with every moment of procrastination, we were also conscious that the risk was only increasing as the tide went out. The more time we spent worrying about dying, the more likely it was that we would die. The absolute worst thing we could do, then, was spend the next five minutes discussing our medical histories and deep-seated psychological motivations for why we still wanted to jump off high things though we were both in our forties.

For my part, I’d spent the previous year suffering from sciatica, a nerve pain so severe that I could barely sit down — let alone run or jump — and now that I was mostly better I felt like I needed this leap as proof that I was still a functioning physical being. Naomi’s backstory was far more intense. In her twenties, she had broken her back not once but twice, both in jump-related incidents. The first time was at a party, when she leapt off a balcony onto a bouncy castle then had to spend six weeks in a back brace. The second time was snowboarding. She launched herself off a jump in a snowpark and landed badly on compacted ice. And yet, astonishingly, despite these events, she still did not want to lose the part of herself — her inner 20-year-old — who was always ready to take a risk in the name of adventure.

The most terrifying leap of all was into the free fall of middle age

In discussing all this, of course, we had only succeeded in making the jump more unsafe. As we waved at our partners and children who were watching from the shoreline, we listed the good reasons why we should give up and climb down. Deciding not to jump was, in a sense, more heroic and profound than making the leap because, in choosing not to jump, we were demonstrating our capacity for change. By not jumping we would make a brave and bold statement about how we now valued ourselves and our families above some juvenile sense of freedom and wildness. Because the most terrifying leap of all was into the free fall of middle age.

It was at this point we noticed a man climbing out of the sea far beneath us. He was a bald gentlemen in blue trunks, tanned all over with silver chest hair, clearly a good decade older than us, perhaps more. We watched him ascend the hazardous rocks then, after greeting us warmly, launch himself into the ocean without a scream. He came up grinning and started climbing the rocks for a second go.

So, without further delay, Naomi and I both chucked ourselves off the cliff. (She would later admit to me that her jump had been somewhat awkward, entering the water with a back-slap that bruised her coccyx so that she had to spend the next two weeks sitting on a donut cushion — the same one I used for my sciatica. I would later admit to her that I had, in fact, made a notable impact with the sand at the bottom of the sea, indicating that it probably wasn’t deep enough in the first place.) But in that moment, we swam back to shore, exhilarated and ageless. With the sun setting behind us, we emerged dripping from the water, invincible and heroic, even as our children barely looked up from their sandcastles. Naomi and I hugged each other and agreed that we would definitely do it all again next year (even though we agreed later, over WhatsApp, that we almost certainly wouldn’t).

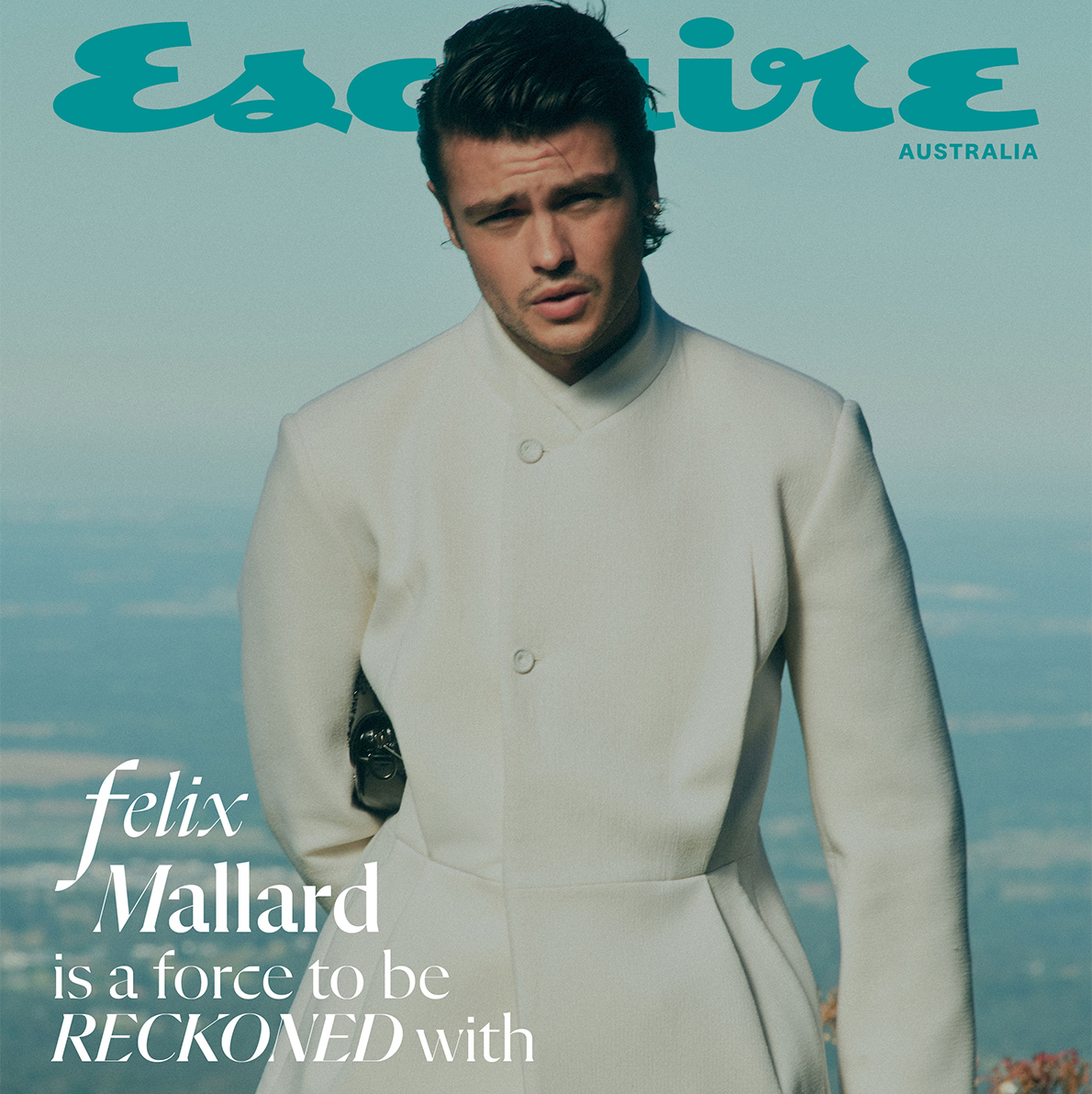

Joe Dunthorne’s most recent book, Children of Radium, is out now. This piece appears in the Summer 2025 issue of Esquire, subscribe here.

This story originally appeared on Esquire UK.

Related: