How cooking classes are transforming the lives of young Australian inmates

From the south side of Chicago to suburban Queensland, cooking classes are transforming the lives of incarcerated people. Here, we travel to Brisbane, where one such program is reconnecting young people in detention with the magic of food, one bowl of native-inspired butter chicken at a time

WHEN YOU HEAR THE WORDS ‘prison food’, you probably don’t think of the best panettone in Italy, or pizza so remarkable that even the Pope knows about it. But around the world, chefs are teaching inmates how to turn raw ingredients into something special – life skills – and a way to connect back to culture, initiating social change that lasts longer than appetites and mealtimes.

In the Italian city of Padua, Christmas cakes at pastry shop Pasticceria Giotto, baked by detainees at the nearby Due Palazzi prison, have been ranked among Italy’s 10 finest panettoni. Taught by the Work Crossing social co-operative, the scheme shows how the simple act of swirling Belgian butter and candied orange through dough can improve outcomes for offenders. According to recent statistics, while the recidivism rate is about 70 per cent for Italian prisoners, for inmates who work behind bars – including those sweating it out in the kitchen – it plummets to five per cent.

Meanwhile, across the North Atlantic, Chicago’s Recipe for Change also offers career-boosting opportunities at the city’s Cook County Jail: Naples-born chef Bruno Abate tutors detainees in pizza-making, and has been praised by Pope Francis in Rome for doing so. The results are so good that The Daily Show presenter and Chinese-Malaysian-Australian comedian Ronny Chieng once declared “that’s right, the best pizza in Chicago [comes from] the biggest jail in America”.

But while Italy has panettone and the US has pizza, Australia has a range of Indigenous ingredients that can’t be found anywhere else in the world. And high-end, hatted kitchens aren’t the only places they’re being plated.

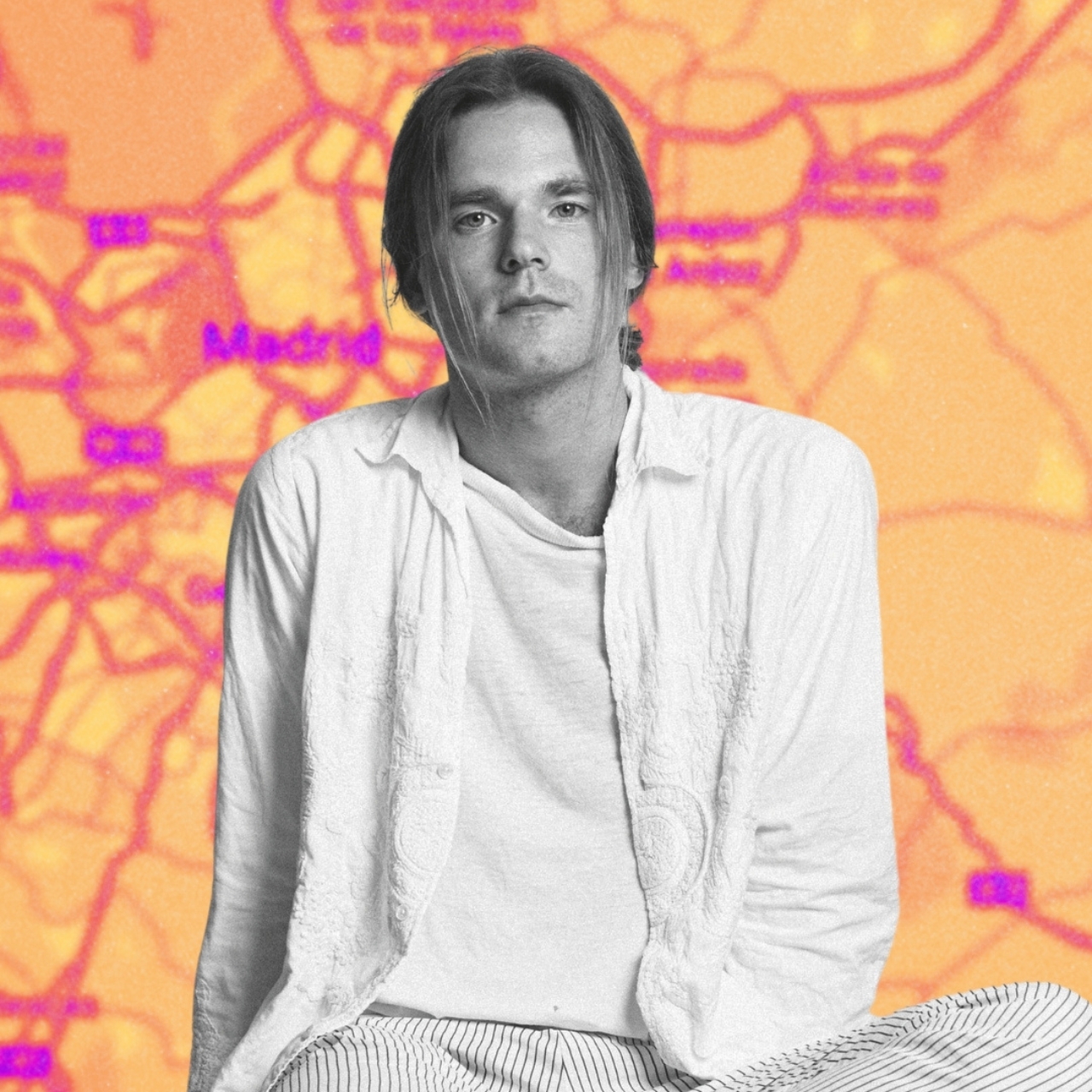

Inside the Brisbane Youth Education and Training Centre, Koori chef Chris Jordan fillets fish, cooks kangaroo, bakes wattleseed brownies and prepares cinnamon myrtle crème pâtissière for young people in prison. He knows firsthand how meaningful a culinary education can be.

“Learning to cook at a young age was a skill that saved my life,” says the chef, who has worked under acclaimed chef and restaurateur Peter Kuruvita and currently runs Three Little Birds, an Indigenous catering company based in Brisbane. As someone who left home early, he appreciates how becoming an apprentice chef gave him focus and literally kept him fed.

“Some kids haven’t had the easiest start to life,” he says. “Cooking is a way they can make amends in their family – a way of giving and a way of providing for their family or making a new start.” It can also offer a career path when the odds are against you. “Food is a really important commodity to young people caught up in the youth justice system,” Jordan says. “Often their crimes themselves are due to the lack of basic needs such as food, leading them to doing whatever it takes to access it.”

For First Nations detainees from remote communities, learning about Indigenous ingredients, their medicinal properties and traditional lore can be especially restorative. “This connection helps our students feel valued and respected and leads to many sharing stories, totems and experiences from home, developing their self-confidence and pride in their culture.”

Native produce – like honey myrtle, river mint, sunset limes, strawberry gum, wild thyme and lime berries – flavour Jordan’s lessons. Many of these ingredients are grown by the chef at the centre, with inmates helping to cultivate the produce. Some detainees will end up completing a Certificate II in Cookery course, which creates a pathway to a career in hospitality. Butter chicken is one recipe students are required to master as part of the course. But they’re schooled in a version that features kutjera (bush tomatoes) and native myrtles, reflecting thousands of years of Indigenous culture.

“I had one of the boys smell the lemon myrtle, he instantly smiled and said, ‘My Grandma used to tell me to wash myself in lemon myrtle leaves’ when his skin was sore. He was so happy to use it in the lesson. [He] also asked to take some back to use for his shower that night.” Namas, a raw fish dish with Torres Strait origins that Jordan has adorned with mountain pepper and lemon myrtle, is also a favourite among students.

Beyond the food they cook and eat on the inside, young detainees have also levelled up their catering skills through the program. They’ve prepared dishes for the FIFA Women’s World Cup and Queensland State Library; at last year’s Rangebow Festival on the Sunshine Coast, they garnished quandong puddings with wattleseed and macadamia brandy snaps, and infused the custard with bush chai from local Indigenous elder Aunty Dale Chapman, who runs Indigenous food business My Dilly Bag.

“The kitchen does not make it happen,” Jordan says, nodding to the stripped-back set up of his workspace inside the centre, where, owing to safety precautions, facilities don’t allow for gas or fire. “It’s the people, the passion and the ingredients,” he says. “We have to use a grill plate on an electric stovetop just to get the charring effect onto the meat or damper, but it still replicates the taste of char,” Jordan adds. “Anything is possible.”

It was chef Kara Pulou from local catering company Kuppibunda Kitchen who introduced Jordan to the initiative at Brisbane Youth Education and Training Centre. She, too, has witnessed the transformative impact of teaching young people in the prison system how to cook. “All it takes is one person to inspire and believe in them, despite their background, cultural or social status,” she tells Esquire.

These classes might direct students towards promising careers, but not every story has a fairytale gloss. It can be hard for some to say “no to the old life”, as Jordan acknowledges, and ongoing support and a safe place to live are needed to keep them on a steady track. “We are forever hopeful that, one day, it will happen for these young people,” says Jordan. “Currently, there’s a young chef who started his first-year apprenticeship at GOMA [Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art],” he says. “We’re working towards collaborative events where he can start to express his own identity on the plate.”

While the hospitality industry can possess the veneer of high-life glamour – champagne, caviar, celebrity status – for Jordan, teaching in detention offers a return to the simplicity of cooking, which is rooted in a sense of community.

“This kind of work is often unrecognised, unappreciated and under the radar,” he says. “But there is no award or medal that compares to the feeling in your heart and soul when you know that this connection to food can be life-changing.”

Related:

8 of the most nutritious meal delivery services in Australia