BUBBLING WITH SPRAY PAINT, a flame-like graphic on the wall of a tunnel beneath the city of Melbourne reveals the word ‘Renks’. The word represents the alter ego of one of the country’s most prolific graffiti artists, a member of the infamous CI, BOT, XTC, GSD, IMOK, 70K crews. 70K crew. He’s never formally spoken to the media about his practice – until now. “I’ve had 360 charges for painting trains and stuff like that. I was among the first in the country to go to jail for graf,” reflects Renks, with a degree of discomfort. “You know, I remember being really young and being like, ‘Oh, graffiti is something that will never be commercial or cool’. And I couldn't have been more wrong.”

Graffiti has come a long way since the ’90s, a time when Renks’ crew 70K was subject to a sustained police campaign that made national headlines, leading to two members fleeing the country for more than a decade. Flash forward 30 years and Matt Adnate, the winner of the 2024 Archibald Packing Room Prize – one of the most celebrated accolades in contemporary Australian art – is being lauded for his roots in the graffiti scene. His portrait of Yolngu rapper, dancer, artist and actor Baker Boy was created using synthetic polymer and spray paint. And it’s not just contemporary art that’s under the spell of graffiti culture. From fashion to music, graphic design and even mainstream advertising, the language of the street is everywhere.

“I guess how it’s [now] perceived in the wider world . . . being taken in by capitalism . . . I couldn’t have been more wrong,” Renks acknowledges of his initial impressions of the scene. His point speaks to the eagerness in popular culture to embrace and co-opt certain elements of graffiti culture – the mystique, the creativity, the thrill of aligning with the anti-establishment – while opting not to acknowledge the desperation and crime that so often fuels the art.

To early pioneers like Renks, this evolution has been fascinating, and somewhat unnerving, to observe. “For me, the art of graffiti will always remain the same,” he shrugs. “It’s a dark adventure.”

But let’s be clear. For all the business owners, or even private citizens, who have woken up to find their shop front, home or But let’s be clear. For all the business owners, or even private citizens, who have woken up to find their shop front, home or favourite public space defaced with graffiti – we hear you. It is an illegal act – and an inconvenient one to clean up at that. The question therefore becomes: how has a form of expression that is most often criminal come to be embraced in the most mainstream of spaces?

I meet Renks at a cafe inside a well-known building in the Melbourne CBD. He speaks with confidence and candour, his reflections punctuated with thoughtful pauses, which hang in the air like particles of paint. We begin with his origin story: Renks was born into a family that embraced bohemian values, which sowed the seeds for a profound yet dangerous artistic journey. “I guess they were hippies. My dad was a house painter . . . I got to travel a lot as a kid,” he recalls of a childhood growing up in Frankston, a low-socioeconomic suburb outside of Melbourne.

Outside of trips to Nepal and India, Renks’ home life wasn’t perfect. “It was pretty fucked up. There was a lot of fighting and arguing in the house. So it wasn’t like a peaceful home,” he says, acknowledging how the lack of safety pushed him – as it does many young writers – to seek adventure outside. “When home doesn’t feel like a safe place, you go out and think for a lot of the time. It’s always those people who are pretty comfortable with risk and danger.”

At 12, he was already teetering on the edge of the law. “I remember when I was going out, my dad found a backpack full of crowbars, bolt cutters and paint – just everything a 12-year-old shouldn’t have.” His father was nonchalant about it. “Well, just don’t get caught,” he said, effectively greenlighting Renks’ journey into the subculture of graffiti.

He refers to being hit by an epiphany around that time, underneath a well-known Frankston bridge. There, he spotted a piece that opened his eyes to an underground art world. “I was like, That’s sick! You know? It just clicked . . . I was like, I want to do this.”

Fuelled by fascination, Renks and his friends set out on a mission in the dark alleys of Melbourne, armed with nothing but paint and ambition. “In Frankston, there wasn’t much going on. So, there’s a lot of trouble you could get into.” Around this time, the essence of Frankston graffiti emerged. It wasn’t just art but a mix of energy and danger. “Frankston style . . . had a really, like, aggressive and funky feel to it,” he says. The thrill of the chase amplified his interest, and the streets became both his canvas and his playground.

How has a form of EXPRESSION that’s almost always criminal come to be EMBRACED in the most mainstream of spaces?

Amid the chaos, creativity thrived. Renks’ obsession with graffiti flourished when he embarked on a fine arts degree at a prestigious college in Melbourne. “I eventually went to college. I rocked up and I was just like, ‘This is what I do. I do graffiti’.”

The collision of art and rebellion became clearer to him during this time. “I realised a good throwie could have the energy of a Caravaggio painting,” he says, referring to throw ups, a fast, impromptu graffiti piece, generally featuring two colours and a cartoonish bubble font for quick execution. “But I was kind of a purist and saw graffiti as its own thing.”

At college, Renks met another artist named Bonez. “I guess we were misfits in graf and in art.” His crew’s name, 70K, stands for ’70s Kids’. He laughs about its inception: “It was just a joke crew, really. It got real because it was getting noticed . . . we were doing really ugly graffiti.”

Style is the unique trademark of graffiti crews – it’s the aesthetic that bolsters the reputation or voice of a crew with colour, bold lines, halos or arrows. 70K defined their style through ugliness, but it wasn’t “a deliberate thing to fuck with the scene to piss people off”. “We were just anti everything. Anti- police. Anti-capitalism.”

Yet the lifestyle came with hardships, which ended friendships and fostered turmoil within and beyond the artistic community. Renks’ crew faced constant threats. “People get jealous,” he says of 70K’s notoriety.

“We started getting followed,” Renks says, detailing the immense pressure they felt from the law, particularly during the 2006 Commonwealth Games, when the Victoria Police sought to convey a sense of control of the streets. As the pin-up boys for anti-authoritarian crime in the state, 70K became the subject of a targeted police campaign. The clash reached boiling point when the crew spray painted a message with extreme anti-police sentiment – one that would shock even the most liberal of people – on the side of a memorial train. The train was commemorating police officers who had died in the line of duty. The graffiti message: ‘Fuck dead cops’.

Members of the crew claim the act was a reaction to years of police harassment and brutality. Unsurprisingly, it made things worse, and eventually, the law caught up with them. Many members of 70K – Renks included – served out various sentences, but the police didn’t drop the case there. In May of this year, after returning to Australia following 20 years living abroad in the UK and Hawaii, 70K member, Stan, was arrested and eventually sentenced to a two-year community corrections order and 300 hours’ community work.

When sentencing Stan, magistrate David Starvaggi didn’t mince his words. “You have to understand . . . that graffiti is nothing other than criminal damage committed or perpetrated upon either public [or private] property . . . This sort of offending is an absolute scourge and blight on society.”

THE GRAFFITI SCENE established by punk outsiders like Renks began shifting from political anarchy to creative self- expression in the mid-2000s, when artists like Rhys John Kaye were entering the scene. When I link up with John Kaye, he’s in his cluttered Melbourne studio. Grey light is streaming through tall windows, illuminating splashes of colour on canvases leaning against the walls. When we start talking, there is a whiff of nostalgia to his words – informed, no doubt, by the raw edges of a life lived on the streets.

“I pretty much went on the run. I had problems in Queensland, so I came to Melbourne, and then some shit blew up here and then I went overseas. The first couple of decades [of my life] was just that kind of shit.”

From a young age, Kaye found himself drawn more to the vibrant tags that decorated urban landscapes than to the mundane realities of life on the street. “I was drawn more to graffiti than dealing and stealing because it was creative,” he reflects, going on to say how graffiti served as both an outlet and a refuge. “Whereas some people are purely in a destructive mindframe . . . I think I just enjoyed the mix of creativity and adrenaline. I did art. And it was really obvious what that was for me – an escape. Graffiti was more about crime or survival. And there was obviously an overlap, but [graffiti and crime] had different intentions.”

As he witnessed things escalate with friends caught up in the traps of the dangerous lifestyle, Kaye’s relationship with the ‘art’ side of the culture solidified. What started as an escape from chaos gradually transformed into a form of expression – an exploration of identity. “I feel like it was a lightbulb moment. I was like, This is like a catalogue of work that marks a side of me.” His influences became more discerning. “I was gradually introduced to things. I remember people being like, ‘Oh, this is Howard Arkley and he uses an airbrush, or this is Picasso and he sprays paint like this’.”

“I realised a good THROWIE could have the energy of a CARAVAGGIO painting”

Transitioning into the gallery was a natural evolution for Kaye – one that allowed him to retain the sparks of his street practice. The art world has embraced his work. In the last couple of years, he’s held solo shows at Melbourne’s Brunswick Street Gallery and No Vacancy Gallery, and has been asked to speak on the subject of graffiti at some of Australia’s most esteemed public institutions, Home of the Arts (HOTA) and Brisbane Powerhouse among them.

Historically, though, the Australian arts establishment has kept graffiti at arm’s length. If an artist is going to be taken seriously by galleries and museums (and probably be accused of ‘selling out’ by their peers), they can’t risk ending up in jail for marking property. Lachlan MacDowall, an Australian scholar of graffiti and street art and Academic Director at Melbourne’s The MIECAT Institute, spells out the borders between street art and fine art: “There’s definitely a sense for some people that illegality and informality is an integral aspect of graffiti. So, there’s some limits to how this can really be recognised within institutions,” says MacDowell, who’s researched the history and aesthetics of graffiti for more than three decades “And I think people recognise in their own minds a distinction between work that’s done without permission – work that’s not commissioned – and more formal work.”

But he notes that these rigid modes of thinking are shifting, as graffiti continues to penetrate the mainstream.

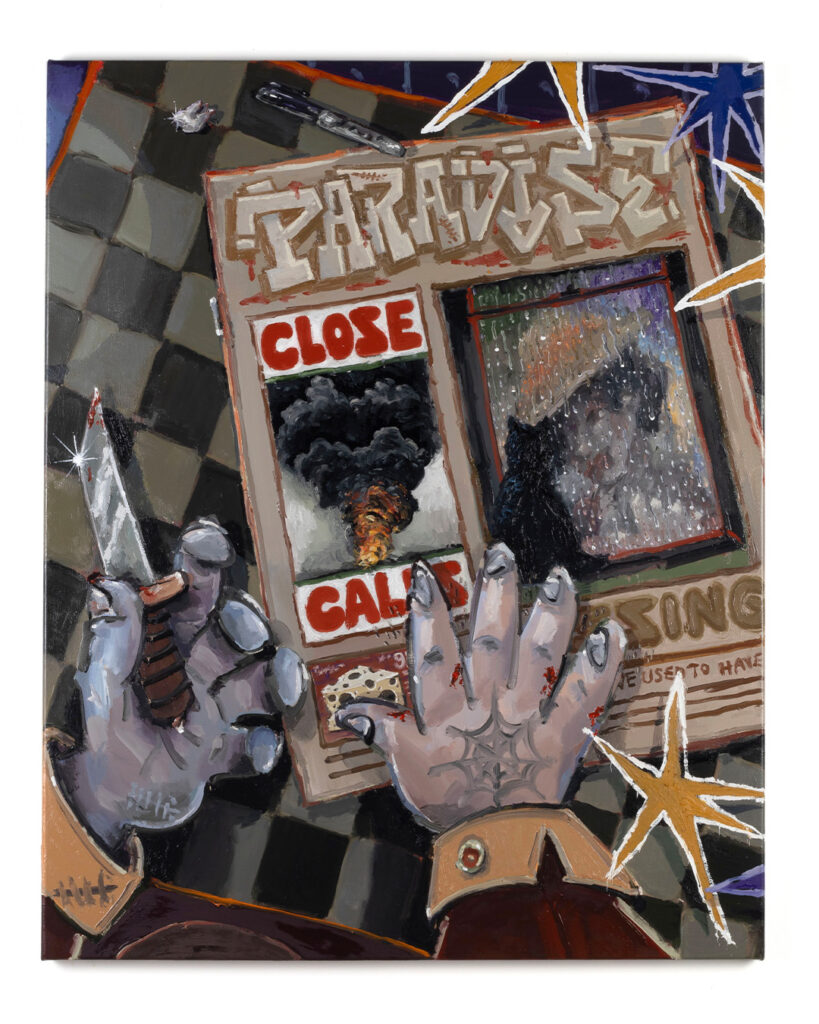

“From graffiti, I bring to my artwork the energy that it’s applied with,” says Kaye, describing how he seeks to capture the spontaneity of his street work on the canvas. “I like the one shot – there’s no fixing things too many times. It’s not overworked. The energy feels left behind with it and the paint gives you a story of the circumstances it was made under.” But he deliberately distances the style of his artworks from familiar graffiti techniques. “I purposely don’t use airbrush or spray paint, because I don’t want it to look too much like it.” By working with oil paint instead, Kaye strives to carve out an identity separate from his graffiti roots, despite its persistent influence. At the same time, he acknowledges the struggle of shedding the persona that comes with identifying as a graffiti artist. “I think it’s been a really long process of breaking away. Graffiti gives you this shield to hide behind. But art is exhausting if it’s not real, so I’ve started to push myself forward by removing the shields and becoming more honest.”

KEEPING YOUR WORD, because your word is all you have, is a sentiment that runs through the veins of street culture all over the world. As I speak to Kaye, the words of Mr Muscles, a graffiti artist and rapper from the group Posseshot, spring to mind. On the track ‘First Name Basis’, Muscles raps: “I’m known for roamin’ with the illest bombers, and I know cooks who put love in their mix like Nonnas, trust me, you’re never wrong if you’re honest”. (For the uninitiated, ‘bombers’ are graffiti artists who leave an explosion of tags in one location; ‘cooks’ refers to cooking drugs).

Comprised of Kharni and Muscles, the rap duo Posseshot stands out as a powerful testament to the intertwined worlds of graffiti and hip hop. “The whole process that we do is exactly the same as graf,” Kharni insists of the similarity between the way they make music and the way they paint. “Every time we make a track, we rock up, we make it on the spot, we do it from start to end. We have a similar process every time. And with our music, personally, we don’t revise shit; we don’t come back to it and add touches. It is what it is; we just bang them out like they’re pieces.”

“It’s pretty hard to avoid – the writing’s on the wall, literally,” Muscles says of graffiti’s growing omnipresence in society, as well as the diversifying community at the heart of the scene. “Like, you can get tradies that have a tag, you’ve got chefs that have a tag, you’ve got lawyers that have a tag . . . because Melbourne is a big melting pot of different cultures. Graf is common ground; you become friends over style. It’s how we win the [culture] war because it’s about art.”

“There’s some limits to HOW GRAFFITI can really be RECOGNISED within INSTITUTIONS”

The immediacy and rawness that characterise Posseshot’s music echo the ethos of graffiti – art that springs from intuitive expression. Muscles elaborates on this alignment: “Working in your environment, using what you have, just pure expression, getting it done then and there. It’s made very much with the same intention of graffiti.”

The cross-pollination between graffiti artists and rap musicians in Melbourne can be traced to the early ’90s, when, according to Kharni, one of the local scene’s founding fathers, Prowler, was “travelling to the States and bringing back hip-hop tapes, basically bringing hip hop to the culture when no one had heard a lot of this stuff.”

Muscles echoes this sentiment. “The culture was multi- elemental. You understood all the elements: DJing, MCing, breakdancing, graffiti [and knowledge of the culture]. If you can express yourself in all those different ways . . . your stocks are up.” In rap, like graffiti, the credibility of an artist comes not just from partaking in the culture but from the lived experiences that inform your expression.

“The reality is that no one actually wants to hear your rap. But if the bloke’s actually a burner, you might want to listen to what he says,” Kharni says. (A burner is a graffiti artist who paints elaborate, time intensive, large-scale graffiti paintings.) “It’s like in America, where people who are actual gangsters take the mic. He’s not just sitting home in a metaphorical world writing letters down.

“Graffiti has always been about being original. It’s like a skate park: you show up and prove yourself. There’s no nepotism. You can’t buy your way into it. You either have the style or you don’t.”

But Kharni notes a growing concern. “What is being proliferated now is more of [the] superficial level of what the culture is about. There are dudes that have put in serious work, and I don’t think they’ve ever worn TN’s,” he says, pointing out that wearing the graffiti ‘uniform’ – Nike TN Air Max Plus sneakers, spray jackets, balaclavas – doesn’t certify anyone’s place in that world. Yet head to any NRL match, rap gig or breaking event, and you’ll see kids from all over the socioeconomic spectrum dressed like eshays, having never uttered a word of pig latin. But such is the appeal of graffiti culture right now: it is inadvertently driving fashion trends.

THE INFLUENCE OF graffiti on men’s fashion is something Sydney-based streetwear designer Roman Jody has watched develop over the last few years. In 2017, while studying at Parsons School of Design in New York City, Jody crafted a hoodie that blended street art with wearable design. “I thought it would be mad if I tagged it,” he says. It marked the inception of his brand, Jody Just. This initial foray into fashion opened doors Jody hadn’t imagined. “The tagged stuff was always a one-of-one thing; it wasn’t mass-produced. It was abstract and obscure.” In 2019, he introduced a collection featuring these tagged hoodies, and to his delight, they garnered attention within the local rap scene, reinforcing the idea that graffiti could find a home in contemporary fashion.

It’s an idea that first sprung up in the ’80s, when American street artist Keith Haring collaborated with British punk designer Vivienne Westwood, his illustrations appearing on pieces from her 1986 ‘Witches’ collection. Subsequently, luxury brands from Louis Vuitton to Vetements and Off-White have created collections inspired by graffiti iconography – in 2001, Louis Vuitton invited US artist and designer Stephen Sprouse to scribble the brand name, tag-style, over a collection of expensive leather bags. Today, the collab is still referenced as one of luxury fashion’s most iconic. Meanwhile, avant-garde e-commerce platforms like SSENSE are peppered with products from independent designers that feature street art-inspired logos and graphics. What sets Jody Just apart from some of these names is his authenticity.

“I grew up in Chatswood [on Sydney’s North Shore]. Since the ’80s, it’s been a spot where graffiti has taken centre stage. We had a big train station, and throughout the ’90s, dudes like TAVEN and DMOTE would paint there,” he says, referring to two of the Sydney scene’s biggest pioneers. In his teenage years, Jody’s daily commute was a journey through an ever-changing gallery of street art. “Catching the train to school every day, I’d see heaps of panels and tracksides, paying attention to different writers and stuff,” he recalls. (A panel is a small piece of graffiti on a train carriage, usually painted under the windows and somewhere between the doors; a trackside is a graffiti work visible from the inside of a train along a railway line.)

Jody first picked up a spray can at the age of 14. “A couple of my friends got schooled and shown the way,” he says. “There were two ways to go with it: the art side or the criminal path. I’ve always seen it from the art side.” To Jody, graffiti is not merely vandalism; it’s a deeply creative act imbued with personal significance. “There are some people who want to paint spots that are really red hot for the adrenaline rush or notoriety,” he notes, “but if you do it for that side of things, you’ll end up being caught up in other shit like racking, xannies, and crime,” he says, referring to stealing and taking the anti-anxiety drug Xanax – two trademarks of the culture. Like Kaye, Jody recognised that many who painted for notoriety became entangled in the darker aspects of street life, so he found himself reviewing his own life choices.

“I knew I wanted to move to the States,” he says, acknowledging the creative opportunities and fresh start that lay beyond Australian borders. In New York, he began to see how graffiti and fashion were intricately intertwined. “My stuff has always been tattoo and graffiti adjacent.” He explains that many of his favourite tattoo artists also come from the graffiti scene, and so it was a natural progression for Jody to draw inspiration from both.

Back in Melbourne, Renks, also, has taken up tattooing, learning the craft from industry legend Johnny Dollar, who has a studio on Punt Road in Richmond. As he sits crouched in front of a client, Renks pierces their bloody skin with black and blue ink, drawing out letters in his infamous Frankston style.

“This style was always about the energy, the angles. With the tagging it had a really aggressive and funky feel to it,” Renks explains. “A lot of the letters would start smaller and then go bigger and just have this … boom! kind of presence.” He finishes the tattoo and takes off his gloves, admiring the graffiti he once painted on walls, now adorning human skin. With its infiltration of popular culture, does he think the artform that put him behind bars is at risk of losing its soul?

“As long as it’s illegal, as long as it’s free, as long as it’s fun . . . graffiti will always have an impact.”

This story originally appeared in the September/October 2024 issue of Esquire Australia.

Find out where to buy the issue here.

Mahmood Fazal is a Walkley award-winning investigative reporter. On the outskirts of his crime writing, Mahmood is currently compiling a book about wine. It is an extension of his Instagram page semiautomaticwine, where he experiments with journalism, automatic writing and poetry to demonstrate the meaning of his favourite wines.