Uncorked: The thinking behind Australia’s most enigmatic Pinot Noir

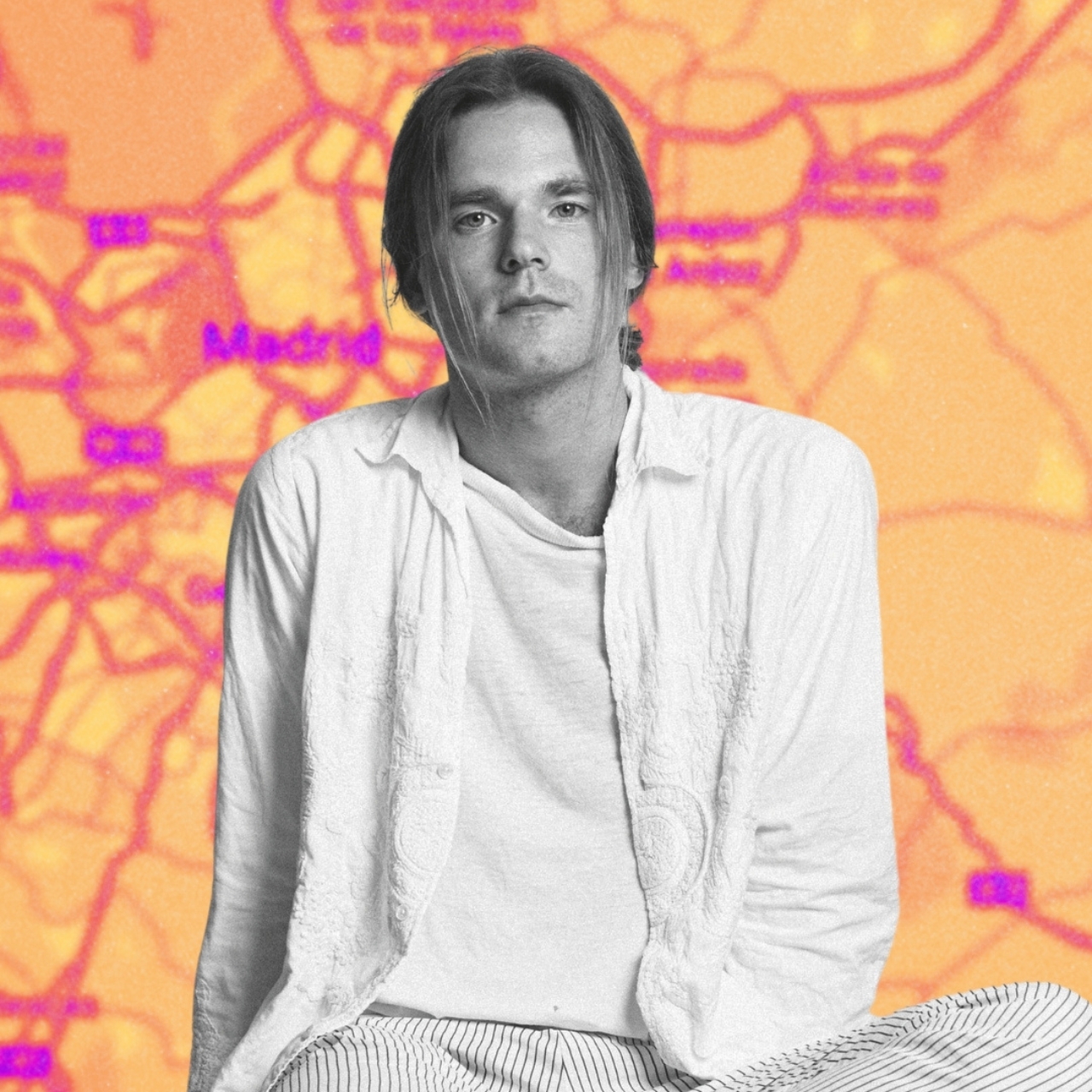

Mahmood Fazal travels to Victoria’s Great Dividing Range to meet a minimal intervention winemaker who is known in certain circles as ‘the master of Pinot Noir’.

Mahmood Fazal is a Walkley award-winning investigative reporter. On the outskirts of his crime writing, Mahmood is currently compiling a book about wine. It is an extension of his Instagram page semiautomaticwine — where he experiments with journalism, automatic writing and poetry to demonstrate the meaning of his favourite wines. Uncorked is his take on a wine column; a romp through the bottles, varieties, phenomenons and personalities that colour the world of wine today.

In Daniel Rutter Long’s sketchbook, buried in the State Library of Victoria, the pharmacist and painter renders his experiences of the Victorian landscape throughout the mid-1800s in a series of ornate impressionist watercolours. Long’s painting, Mossy Face, captures a snaking river in Gippsland as the slopes of emerald and apple coloured hills wind down into the glistening freshwater. Leafing through the sketchbook, I can’t help but think of winemaker William Downie’s story where the active role of agriculture becomes, both literally and metaphorically, the means by which he comes home.

The wines of William unfold like watercolour Rorschach tests of Guendulain Farm—the winemaker’s home in Gippsland on the foothills of the Strzelecki Range, below the Great Dividing Range. Downie, who has been lauded as an influential pioneer of minimal intervention winemaking in Australia, specialises in unique and expressive Pinot Noir wines that reflect and celebrate the character of the sites he farms and manages.

“When you’re a Pinot Noir producer outside Burgundy, you start out wanting to replicate Burgundy and make wines that taste like Burgundy,” Downie tells American wine-critic James Suckling in a 2016 YouTube interview. “But eventually… you realise that the real project is to make wine like the place you’re in.” Downie cultivates an enigmatic magnetism, likened to a cult-like following, that even includes a group of sommeliers who started a ‘Team Downie’ fan club.

“It’s been a challenging run around here,” explains Downie, as he gestures towards the valley around him. We’re swirling the most recent vintage of his Bull Swamp Pinot Noir in our glasses; when I hold it up for a smell, he points out the $100-plus price tag only just covers the cost of production. “We’ve been in that cycle of wetter winter [and] spring for the last few years. And so when it rains, particularly in November and early December, then we just get smashed. We have little flowering. We’ve had five years in a row of between 60% and 90% crop loss.”

From Burgundy to the Bull Swamp

Pinot Noir is a red wine grape that found its home in Australia, via France, in the early 1800s. It’s a wine that’s typically light to medium bodied, quite bright and fruit forward with strawberry and plum notes when young. It contains flavours that can transform with age, on vine or in bottle, toward a deeper liquorice, smoke-filled, earthy story. It’s a popular wine choice at restaurants because of its versatility. At a dinner table of mixed offerings the wine can size up grilled salmon, duck and beef Bourguignon. I’ve been known to open a bottle of William Downie’s Bull Swamp Pinot Noir at home while spinning The Drones’ Gala Mill record, a kangaroo steak on the grill with some blackberry sauce waiting.

The Bull Swamp Pinot comes from a vineyard planted in 1981 on volcanic soil. On the nose, the 2022 vintage presents a stirring gale of blackcurrants, bramble and soil broods out from the glass. After a swig, a staccato of prunes, beetroot and tree bark forge a distinctive image of Gippsland’s heavy landscape. A circular motion of fresh acidity and structured tannin hold the rhythm of the wine in balance. The reverberating colour and sense of music harks back to Downie’s past.

“I was a musician, a bass player in a rock and roll band. We were a guitar pop band with a slightly dirtier edge, bands like The Church, The Stems. We played with the Hoodoo Gurus one time,” explains Downie. “I used to joke to people that I became a winemaker because after seven years of playing in a band I was still a shithouse bass player.” While playing in the band, Downie began working at his local bottle shop for some extra money, “the guy who owned the shop was like, ‘there’s no money in beer and spirits, we’ve got to learn how to sell wine’.”

For Downie, his passion for music was entrenched in the recording process. And after attending some wine appreciation courses by the wine critic Jeremy Oliver, he realised that making wine and recording music were conceptually the same job. “If you think about your real ideal description of what wine is, it’s trying to capture the truth of a place at a point in time. So that you can revisit that sense of place, at that point in time, in the future, at a time of your choosing.”

Downie points out, “A record is exactly the same thing. You know, you’re trying to capture a performance on a day, in a place, in a way that’s accurate and true so somebody can revisit that performance in that place at another time of their choosing in the future.”

Land first, variety second

Downie was exercising the same creative muscles, substituting emotion and musical instruments with intuition and agriculture.

“I was interested in why a wine tastes the way it does. Very little to do with that was about grape variety. I was never really interested in Pinot noir at all and am still not interested in Pinot noir. I’m just interested in trying to find a grape variety that grows well around here and tells a story.”

Downie started his on-site education working at the legendary Bass Phillip vineyard in Gippsland. Then, he did a stint at Yarra Valley institution De Bortoli, all the while becoming increasingly enchanted by the site-specific precision of wines from Burgundy. It wasn’t long before he travelled to France for work. “I did the first whole year, like vintage to vintage with a gap for the Australian vintage, at Domaine Fourrier. Then worked at Domaine Hubert Lignier I.n 2004 Roman Lignier passed away, and they rang me asking me to come back and lead the winemaking for the ‘04 and ‘05 vintage.”

After trying his hand at buying barrels and setting up a micro-negociant in Burgundy, Downie met his partner Rachel, who was working for the iconic wine importer Kermit Lynch; together they decided they wanted to be small holders, making wine and cheese.

“I think the one thing I really learned when I was in France was that the reason there isn’t a direct translation into English of the word terroir is because it’s a really complicated idea. [But] it’s really easy to simplify to; the influence of climate and soil on the characteristics of a wine. But it has a kind of unspoken, but deeply understood by the French, connotation of cultural connection to place.”

The terroir

The only place Downie believed he could make an honest wine is in the place he was born and raised, “I’m physically part of this landscape. I grew up eating food from this landscape, I’m made up of molecules from here.”

Downie pauses before reflecting on his own connection to place. “And then you realise, well, actually I have very little understanding of this area. There’s at least 15,000 years of Gunai Kurnai connection that I need to engage with, understand and learn about which I’m still really shamefully not anywhere near as far down that track as I should be.”

Shaped by his experiences working abroad, Downie believes that to reflect the true character of a vineyard in the wine,minimal intervention in the natural cycle of the winemaking is essential. “Learning how to leave it alone is actually really complicated and does take a long time to figure out—how to do nothing,” laughs Downie.

The process for William Downie’s wines follows the earliest principles of winemaking; whole bunch grapes are placed in a tank, the tank is covered and the must is pressed after 30 days. Downie adds, “We don’t do anything. No pump overs. No punch downs. Nothing. No temperature control, no addition, there’s nothing—it’s just grapes in tanks.”

In the end, the essence of his winemaking happens in the vineyard, at the mercy of the weather, by tending to the land. “It’s all about agriculture,” says Downie. “What we’re trying to do is figure out how to improve the biodiversity in the soil, so that we can leave the earth better than the way we found it.”

See the first edition of Uncorked, where Mahmood reviews the peerless Giaconda Chardonnay, here.

Related: