How metrosexuality changed the face of masculinity

Thirty years since the phrase was first coined, Esquire looks back on the proud and colourful reign of the metrosexual

IT WAS 1995. I was staring down the final months of my last year of high school before slinking into life’s most tantalising period of freedom. I was also staring into the bathroom cupboard of my cousin, Patrick. Six years older, working a post-grad, entry-level finance job, he was the brother I’d never had and someone I’d long admired – and still do.

He’d weaned me on music that wasn’t on the radio – everything from Iggy Pop to The Smiths to World Party to Public Enemy, R.E.M., Masters at Work and Weezer – and held an eye for fashion that focused far beyond Country Road’s chambray shirts or Shawn Stüssy’s global delivery of skate pants. Pat’s bathroom cabinet – as I learned that evening – was an assembly of grooming products I’d never before seen, and fragrances I’d never before smelt.

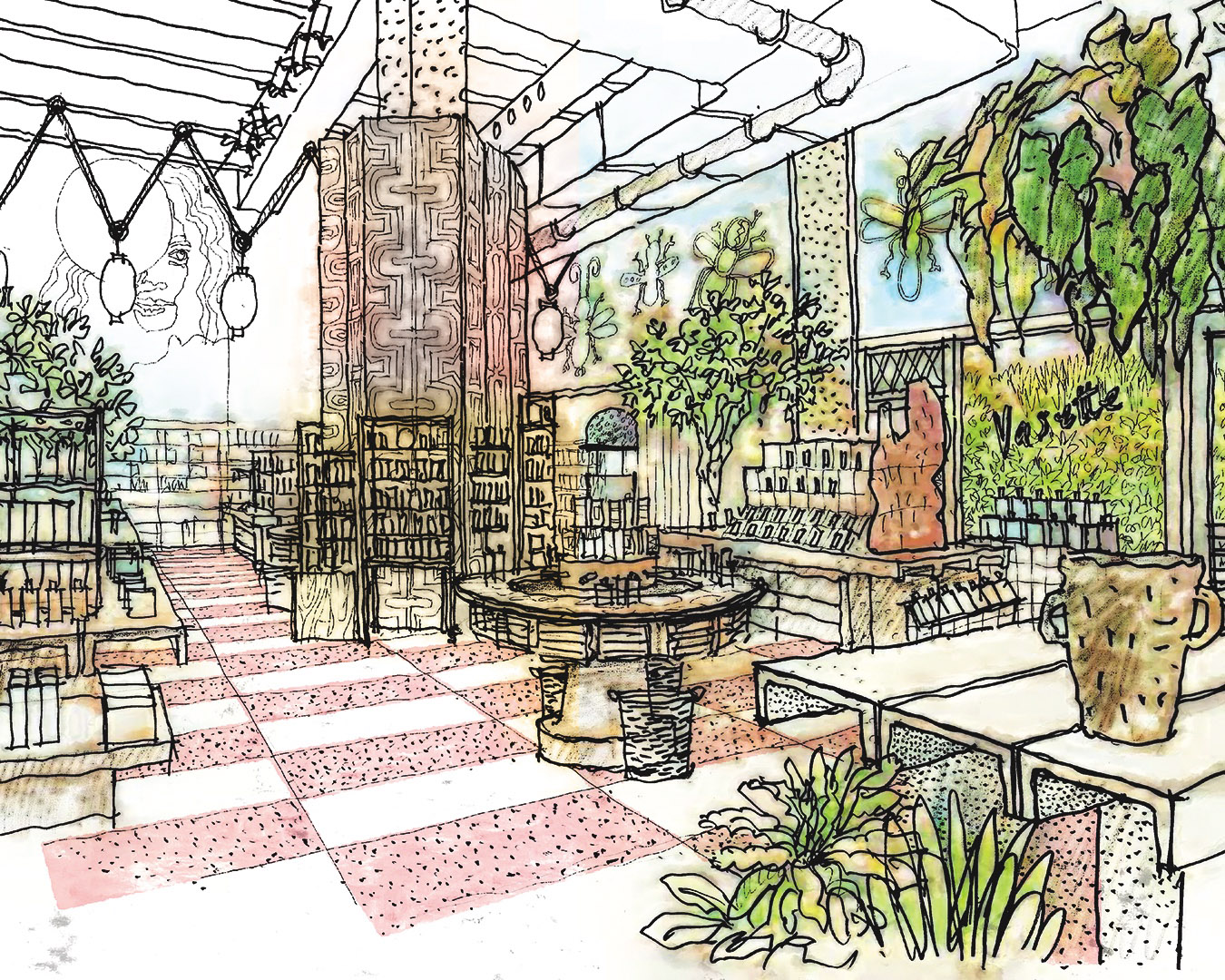

“Grab some of the Issey,” he barked from an adjacent room of the Perth apartment he’d been renting against my aunt’s wishes – a tightly designed studio within an inner-city warehouse conversion, the first of its kind in our remote city and a magnetic beacon of my downtime.

The ‘Issey’, of course, was the tall, opaque bottle of Issey Miyake’s debut men’s scent, L’Eau d’Issey. The layered fragrance was a good fit for my cousin – himself a unique entwinement of elements that I couldn’t quite get a handle on, but which I respected and wanted to replicate. His weekends were spent playing top-level footy, chasing skirt (disclaimer: phrasing from the time), drinking with mates and poring over UK magazines such as i-D and The Face. He was fashion literate and, as I discovered that evening, into cosmetics. He set a tone – a confident and diverse expression of masculinity. He was, as I’d later learn, the archetypal metrosexual.

It is 30 years this November since that term was coined by British journalist Mark Simpson in a piece in the The Independent newspaper called ‘Here Come the Mirror Men’. The article explored Simpson’s attendance at London’s It’s a Man’s World, the tagline for which was, ‘Britain’s first style exhibition for men’. The event, noted Simpson, “proves that male narcissism is here and we’d better get used to it”. What Simpson espoused ran two-fold – that straight men were increasingly doing double-takes when passing a mirror, checking personal appearance and style, clothing and beauty; and that marketers across fashion and grooming had found (and were quickly exploiting) a new slice of hetero masculinity that was eagerly adopting elements of gay culture.

While the march of the ’90s metrosexual that Simpson spoke of was in its infancy, it was enough to be dressed up and glorified in the glossy pages of the men’s mags of the time, Esquire included. Still, it wasn’t until a few years later and the turn of the century (a collection of words that immediately makes you feel old) that the metrosexual came to properly strut to the beat of global pop-culture prominence. By then I’d followed Patrick to London. Well, I’d chased his stories of a sociopolitical climate being propelled and shaped by youthful energy, optimism and a ‘give-a-fuck’ attitude. Anything, it seemed, went. And, to a point, that was true.

Music, as the barometer, was a unique interplay where garage house and garage rock came to emanate from speakers, with new rave, nu-folk and post-Britpop bolstering the soundtrack of the time. So, too, Westlife – though the less said about them the better.

Ecstasy was now mainstream. Having launched out of the gay clubs to lift and dance across the Second Summer of Love and make Madchester seem interesting, it had come to a place of ubiquity in being openly necked by near everyone under 30 near every weekend.

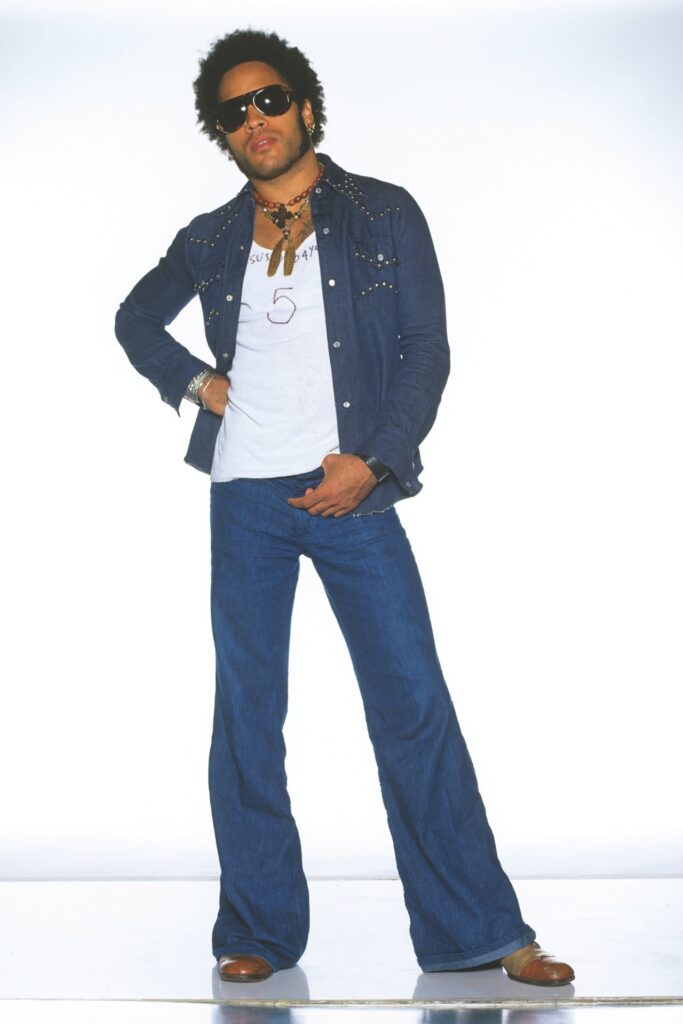

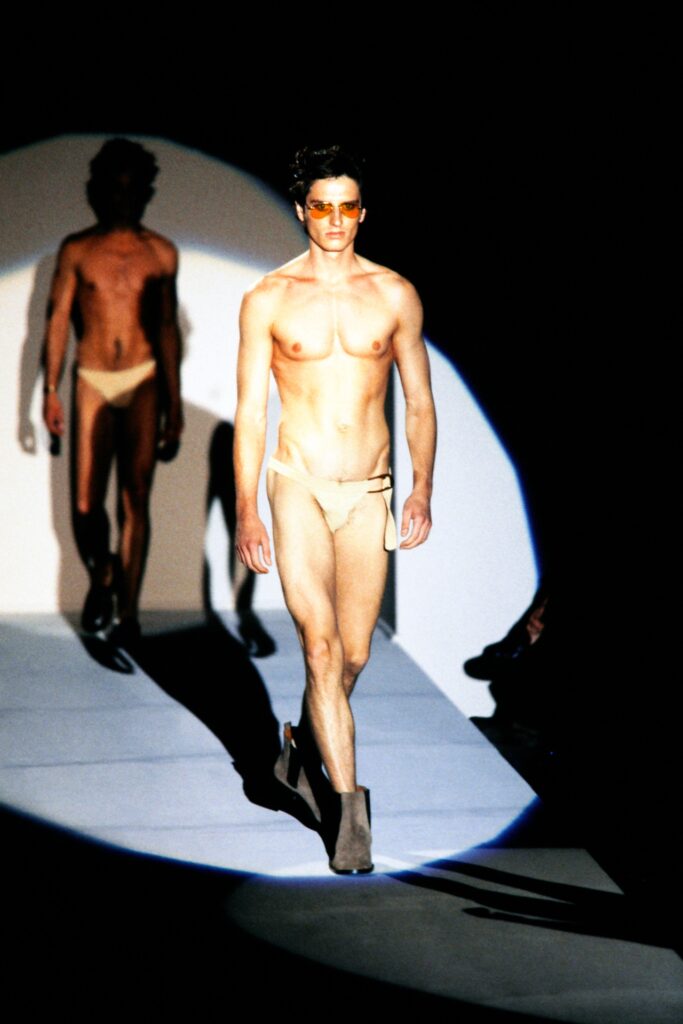

Clothing was open for interpretation, though luxury labels were conspicuous via logoed designs with a rising, elevated street scene (think Maharishi) battling the tightening ways of some denim. By now, Tom Ford had sent a male G-string down the runway (1997), and later (2003) shaved a ‘G’ into the pubic hair of a female model for an advertisement.

It all came to form a rather heady melange – a pick-and-mix period that also offered a newfound sense of acceptance about being, in today’s parlance, ‘fluid’ in finding one’s identity. At this crossroads of masculinity, Simpson returned to better explain and explore metrosexuality in a 2002 article for the US website Salon.

“The typical metrosexual is a young man with money to spend, living in or within easy reach of a metropolis – because that’s where all the best shops, clubs, gyms and hairdressers are,” he wrote under the headline, ‘Meet the Metrosexual’. “He might be officially gay, straight or bisexual, but this is utterly immaterial because he has taken himself as his own love-object, and pleasure as his sexual preference.”

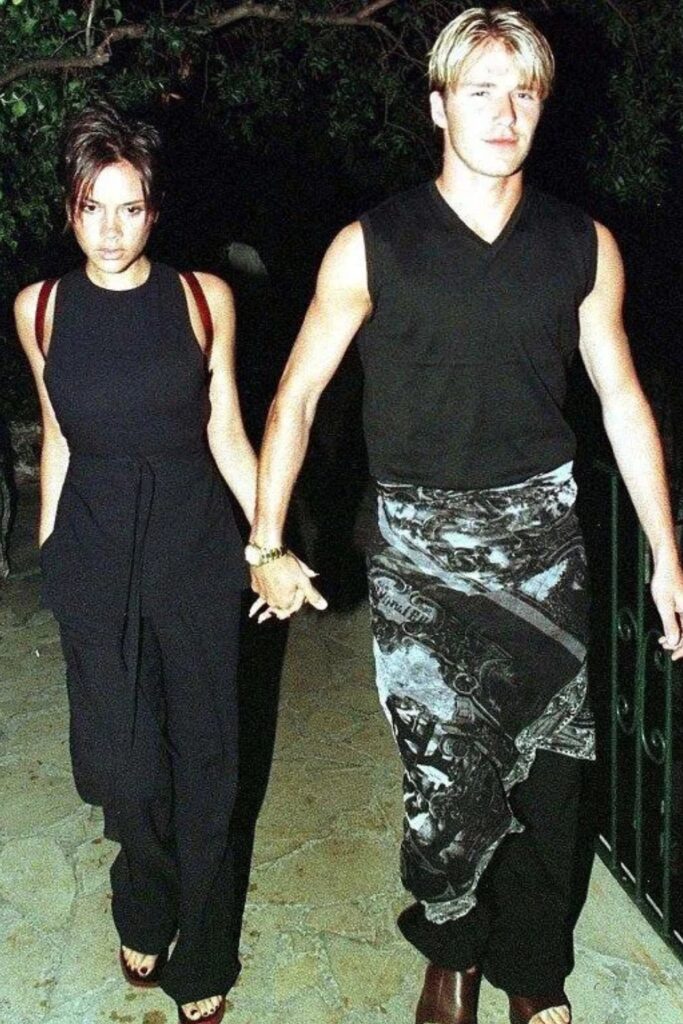

True. And by then metrosexuality had found physical embodiment in David Beckham. Cartoonish he may at times appear today, back then Becks was a deity who led the modern imprint on masculinity (aided by the fact he’d also escaped footballing purgatory following his 2002 World Cup heroics). Beckham was a freakish talent within masculinity’s greatest pantheon – modern sport. He was also that guy who once wore a ‘skirt’ (as tabloids labelled his 1998 sarong), sported a diamond stud earring, married a global popstar, wore pink nail polish, set fortnightly hair trends (while encouraging men to forgo the barber for a hair “stylist”) openly followed a grooming regime and swilled some booze with his mates every now and again.

Equally, it should be conceded, the metrosexual could be a bit of a dick: a try-hard fuelled by narcissism and/or a fragile sense of self-worth – and perhaps the coke that would often line the inside pockets of his fitted Helmut Lang jackets. But the narcissism was never quite to the level of Patrick Bateman’s early ’90s-style of self-obsession. No, the metrosexual was, for the most part, a welcome arrival who was about more than male vanity, who helped march masculinity away from archaic and brutal former iterations. Yes, it was partly a marketing ploy, but its uptake ultimately shifted the needle for the better.

While the metrosexual would eventually become lost in the thick beards and craft beer barrels of whatever that was that came next (lumbersexual?), it opened the door to choice, individuality and acceptance. So, too, cabinets lined with some rather decent scent.

This story appears in the November/December 2024 issue of Esquire Australia, on sale now. Find out where to buy the issue here.

Related: