What I didn't expect to learn from the Beckham documentary

He might've been a football superstar. But David Beckham is a pretty solid father, partner and team player too.

Jonathan Seidler is an Australian writer. This is his column for Esquire.

LIKE JUST ABOUT everyone with a Netflix subscription, I’ve been absolutely living for Beckham, perhaps one of the last big-budget documentaries we’ll be treated to in a while as the WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes grind the streaming wars to their inevitable conclusion and all the major players start shoring up their profligate spending.

A four part saga about football’s most charismatic star and his equally, if not more influential wife, Beckham is refreshing not only for its incredible level of access—boasting candid interviews with pretty much every superstar player, manager and journalist in our new millennium’s football history—but also its frankness.

It’s been a long time since David Beckham was famous for simply being an elite sportsperson. He’s an international icon, a businessman and a multi-million dollar blue chip brand. Assets like him—and his wife Victoria—are typically ring-fenced by large publicity teams at the highest level from dwelling on any sort of controversy, which is why the near-12 hours of interviews wrangled and whittled down by the show’s director (Succession’s Fisher Stevens) makes for such compelling viewing.

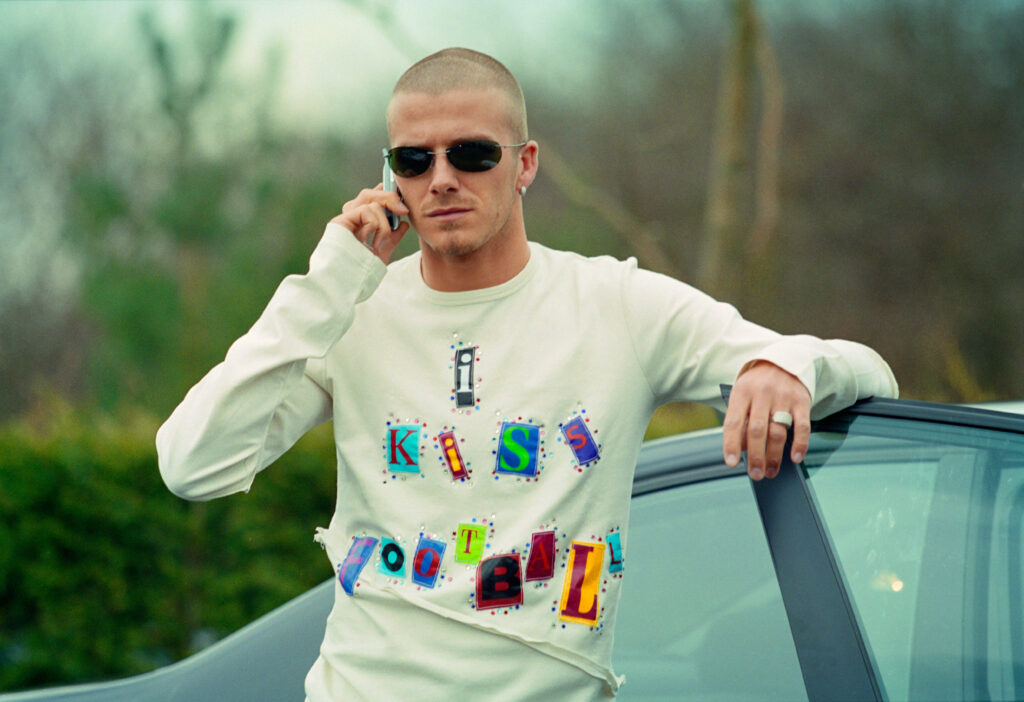

In the show, Beckham tells us a lot about football. But his story also tells us even more about how to navigate the world as men. Throughout my bingeing of the limited series, I found myself mentally taking notes on how he had approached nearly every facet of his life. From his fashion-forward wedding get-ups and vacation saris to his being rejected by multiple father figures and at one point, the entire country, there’s a lot to take away.

Perhaps the most enduring image left of David Beckham is one of persistence. As kids, it’s a trait we all learn is important, whether we’re trying to quit piano lessons or drop out of university courses. But in Beckham we see this taken to the extreme. He keeps training alongside Real Madrid even when their coach bans him from playing another game. He shows up, unflappable in the face of torrential abuse at every Premier League match after dashing England’s hopes at the 1998 World Cup. We never see him crack, or flip out, or storm off the pitch. That he possesses an ungodly level of mental fortitude is hardly in question, but it’s seeing this all unfold sequentially that makes you realise how rare this is in a man.

Equally inspiring is Beckham’s ability to balance superstardom with teamwork. By the time Beckham arrives in Spain, he’s one of the most in-demand celebrities on Earth. Most blokes would probably think that sort of social capital affords them the licence to do whatever the hell they want, Jamie Tartt style. Beckham instead knuckles down on integrating himself into his team, ingratiating himself in particular to Ronaldo and Luis Figa, despite the latter technically playing in the same position as him. He does this time after time at club after club, and it’s a subtle but valuable lesson in what ultimately earns a man respect.

Though he may be a deity to football fans, Becks is not infallible. We learn as much from some significant life missteps as we do from his victories. The most notable of these is a short-lived affair, but racing in for a close second is a photo shoot with J Lo and Beyoncé he undertook while his wife was in labour, not to mention signing with new teams seemingly every few years after leaving United, slingshotting Victoria and his growing coterie of young kids from Madrid to Los Angeles and back again, often with little warning. It’s here that interviews with Victoria allow us to see the impact of her husband’s decisions on her family, which is vitally important. Her clear recounting of her persistent unhappiness, combined with Beckham’s acknowledgement of his significant fuck-ups, goes a long way in demonstrating how families need to work together to stay together, and that this responsibility lies with both parties.

Beckham first became a father in his early 20s, at the height of his career. From the jump, he makes it plain that his kids are a priority to him, often flying out from training to be with them, or relocating his family to be closer to him. This is obviously not a luxury afforded to regular dads, but Beckham could have just as easily only seen his children two to three times a year. It’s refreshing to watch someone that clubs are fighting over to the tune of many millions of dollars still maintain that his kids are on equal footing with his job, which also happens to be the sport he loves. This is not standard practice for elite athletes, or even regular working dads, especially not 20 years ago.

Often, the shows that become water cooler conversation are all hype with little follow-through, especially when they’re about real people. By contrast, Beckham, which will undoubtedly be viewed by millions due to his star power, made me think differently about how I view myself and my relationship to my partner, family and colleagues. As someone who has never sought out role models in the world of sport, I’m surprised at how much the story has affected me. Perhaps it took separating the man from the myth for a brief moment to remind me that the blueprint for how we conduct ourselves as men is always ours to write. You don’t need to be a Premier League diehard to get on board with that.

Jonathan Seidler is an Esquire columnist and the author of It’s A Shame About Ray (Allen & Unwin).

Like all proper columns, this one will be back next week. You can see every one of Jonno’s columns for Esquire here.