In the hands of auteur directors, tennis films finally turn pro

The tennis-movie genre has often been used as a comedic device – the sport of brats and snobs. But recent additions have been far more ambitious, holding up a mirror to society’s deepest cracks

FOR A TIME, the tennis movie had more luck as a comedy. Take Kirsten Dunst in Wimbledon (2004) testing the tightness of her racquet’s strings by tapping the frame, only for it to snap. Or in the mockumentary 7 Days in Hell (2015), in which Andy Samberg plays an Agassi type (fake mullet and all) who, somehow, is adopted by the Williams family and coached alongside Venus and Serena in a reverse Blind Side. There are also plenty of comedic tennis scenes: the tit-for-tat gameplay of Rose Byrne as the quintessential country-club mum in Bridesmaids (2011) is one for the ages.

And so it was: the archetypal on-screen tennis player was a snob or an egomaniac, often both (Shia LaBeouf as John McEnroe in 2017’s Borg vs McEnroe – perfect example). With so many rigid rules in force within a perfectly symmetrical court – stark white lines denoting opposing territories, ins and outs – the game sets up contenders to crack. Also, the sport has long been a domain of the white middle-class. And there’s nothing audiences love more than watching rich kids throw tantrums in public.

But not every director has had luck spinning big serves into compelling scripts. Tennis may lack the dynamism of team sports like basketball, or the rags-to-riches narrative arc of baseball, so its storytelling allure lies in its personalities. Every time they take to the court, players engage in a contactless fight channelled through forehands and backhands, the thwack of ball on multifilament; the racquet becomes an axe. These loner superstars – packages of ambition, but also rage, repression and abandon – are ripe for mining; they’re irresistible to our most cerebral filmmakers, who see tennis as so much more than just a sport.

Take husband-and-wife duo Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris’s Battle of the Sexes (2017). You could take one look at Steve Carell (who plays Bobby Riggs), with his bushy sideburns and thick specs, and feel promised two hours of laughs from his male-chauvinist-pig gameplay with Emma Stone’s Billie Jean King. But what Dayton and Faris realised from basing their film on the build-up to the 1973 exhibition match between Riggs and King was that revolutionary epochs in tennis often mirror what’s happening in the world more broadly.

The film starts with King and the Original 9 founding the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) after being refused equal prize money by the sport’s establishment. But that’s just one side of the coin for King. Once she begins an affair with the WTA’s on-call ‘haridresser’ Marilyn Barnett (Andrea Riseborough), the film also portrays what it was like to be gay on the ’70s tennis scene. Society and sport converge, and King’s sponsorships are at risk if she’s outed. By the time the movie premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival, it had been two years since the US Supreme Court had made marriage equality the law of the land. And so, as you watch the titular match ebb and flow, you’re also witnessing a chapter of history unfolding – one King played a part in engineering.

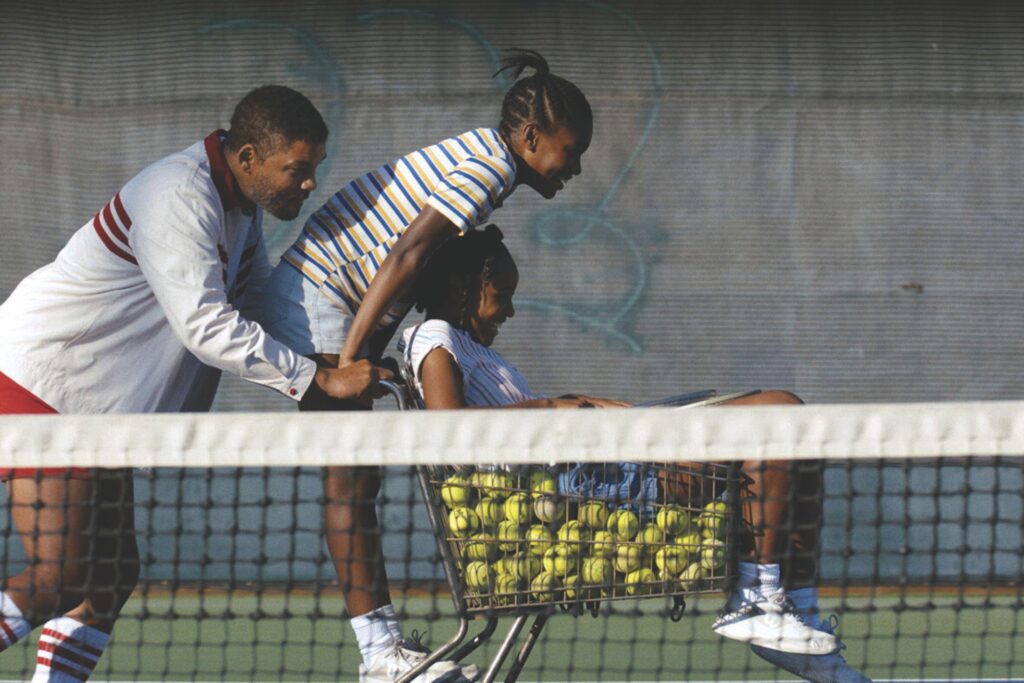

Reinaldo Marcus Green had a similarly lofty goal in recreating the girlhood years of Venus and Serena Williams in the biopic King Richard (2021). The cracked concrete courts of Compton, LA – a far cry from the pristine grass at neighbouring country clubs – weren’t a typical setting for a tennis movie. But that was the point. Yes, this is a movie about the makings of two of the most successful American tennis players in history. More importantly, it is also about two of the most successful female tennis players in history, and the most successful African-American players in history.

As you watch father-coach Richard (played by Will Smith, who won Best Actor at the 2022 Academy Awards, aka the year of ‘the slap’), erect the scaffolding of their early careers, nerves run high as each pole is put in place, often against the backdrop of snobbery, racism and plain old scepticism. The movie encourages you to look beyond the court at how inaccessible the sport was for demographics outside those who governed it. When Venus is on the precipice of stardom, Richard’s dream is not for her to win just yet, but for her to be treated fairly by tennis and its sundry bloodsuckers.

Venus (Saniyya Sidney) might have lost to Arantxa Sánchez Vicario (played by real-life tennis player Marcela Zacarías) at her first pro tournament, age 14, but as she’s greeted by screaming young Black female fans at the exit, you feel as if, ultimately, she’s won.

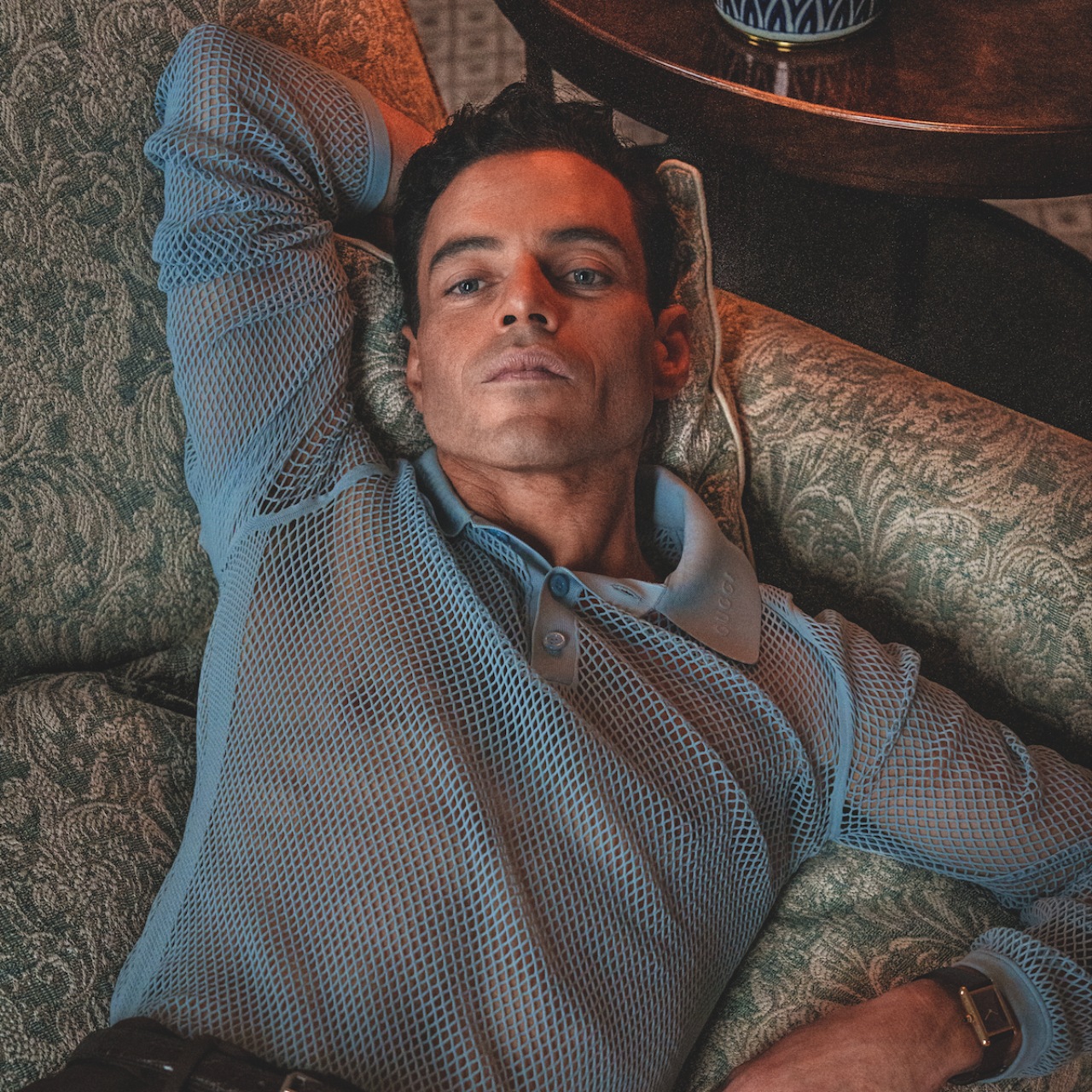

More recently, Luca Guadagnino’s Challengers (2024) became the most shocking tennis movie ever, breaking the pop-culture sound barrier by placing Zendaya, Josh O’Connor and Mike Faist in a steamy love triangle. Written by playwright and author Justin Kuritzkes (this was his first feature film, mind you), the film ties the logic of tennis’ three sets to the logic of a script’s three acts. It’s all in the correspondence between the movement of the ball and the player’s psyche. From the moment Art (Faist) puts the ball in play in the opening ‘Challenger’ match against his former best friend Patrick (O’Connor), physics takes over and all bets are off.

While the tennis movie certainly had a field day of poking fun at the upper-crusters who pay exorbitant membership fees to sip Pimm’s in cable-knit sweaters post frolic, more recent additions to the canon have opted to subvert this trope. The result has seen our most stylish filmmakers depict the sport in ways that differ drastically from the familiar patterns of a television broadcast. Viewed from above, the court’s perfect rectangle forms the ideal mirror to hold up to the cultural zeitgeist, and for filmmakers to express what they care about, visually and sensually. Against the geometric purity of tennis, desire in all its forms can be laid bare.

This story appears in the December/January 2024-25 ‘Summer of Tennis’ special issue of Esquire Australia, on sale now. Find out where to buy the issue here.

Related:

New world order: letter from the Editor

‘American Psycho’ is a perfect movie. Does it need to be remade?