How Oscar Piastri and the McLaren F1 team are helping to save the Great Barrier Reef

The ocean is the hottest it's been in 400 years and climate scientists are warning us the reef is on a one-way track to decay. In an unconventional yet very cool partnership, we get an inside look at how F1 technology can help repopulate our natural wonder

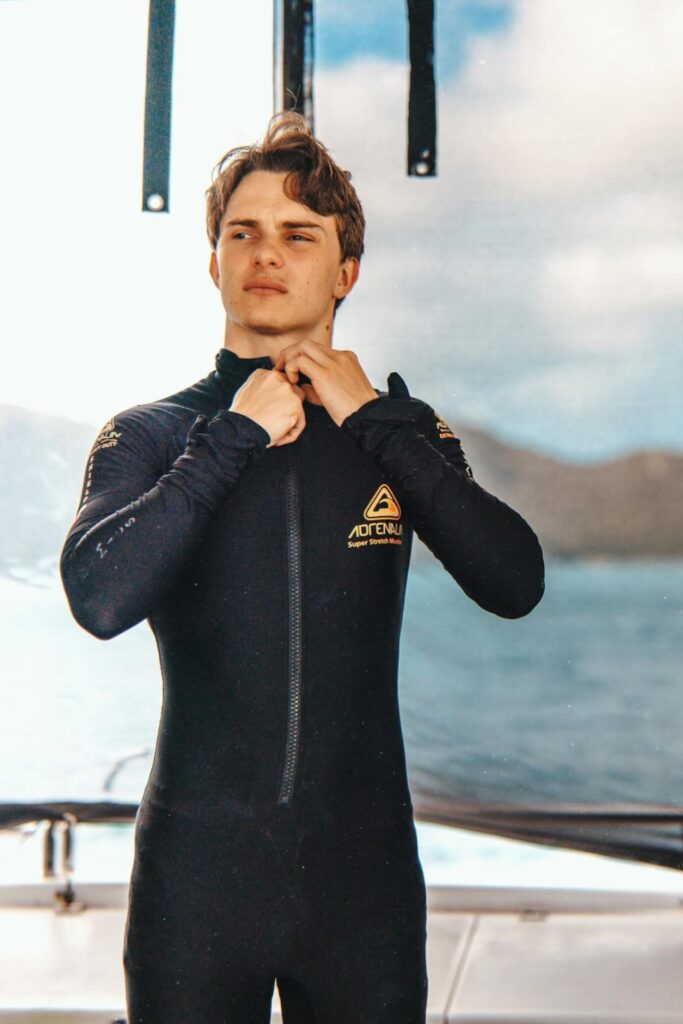

WHEN IT COMES TO ‘moments I thought I’d never find myself in’, bobbing around in the Coral Sea in a stinger suit and snorkel next to Formula 1 driver, Oscar Piastri, turtle-spotting and discussing the state of the Great Barrier Reef, has got to be up there.

Like many unexpected positions I’ve found myself in, I’ve ended up here out of raw curiosity, because since McLaren Racing announced a sustainability partnership with the Great Barrier Reef Foundation earlier this year, I’ve been wondering (and frankly, quite skeptical) about how this pairing came to be. What business does an F1 team have talking about sustainability?

It turns out that just like any other relationship found within the ocean: this is a symbiotic one. As Piastri tells me, it’s a partnership that’s rooted in a shared interest in data, optimisation, engineering and achievement. As for why he’s fronting the campaign? Well, as someone admittedly still growing into his role model era, what better avenue to do so, than helping bring awareness to the plight of one of his home country’s most vulnerable and ancient natural wonders?

At around the same size as Italy, the Great Barrier Reef is home to more than 9,000 biodiverse species. Its decline, led by mass coral bleaching events, invasive species, pollution, overfishing and extreme weather is happening right in front of our eyes, and scientists have been warning us the window to save the reef is closing.

Scientists have already sounded the alarm this year when they witnessed the most extensive and extreme mass bleaching event on record, and the fifth one to occur in eight years, caused by global heating. But just a few weeks ago, another new report came out that showed ocean temperatures in the Great Barrier Reef are at the highest they’ve been in four centuries and without major action to rapidly cut greenhouse gas emissions, said the scientists, “we [as in our generation] will likely be witness to the demise of one of the Earth’s natural wonders.”

The thing about coral reefs, however, is they might have survived for millions of years, due to their natural resistance and ability to recover. But in recent times, the ‘beating hearts of our oceans’ have become the most vulnerable ecosystems on the planet. And now, thanks to the ongoing frequency of severe stressors, they need help.

The Great Barrier Reef Foundation is the leading organisation working to restore the reef through growing and harnessing a nursery of heat-tolerant baby corals – think IVF but for coral – which are deployed annually into the water with the hope they’ll flourish and bring life back to the reef.

The issue is that this method, despite its high success rate, is a technological and labour-rich process that takes time to see success. And as anyone who has worked with government or large-scale corporations knows, securing funding and a helping hand can be just as time-consuming, red tape-wrapped, powerpoint-heavy and laborious as growing and fostering the delicate marine lifeforms themselves.

According to the foundation’s managing director, Anna Marsden, this is made even more difficult by the rise of greenwashing – which is at an all-time high, by the way – and, together with a lack of patience and an increased trepidation in the sustainability sector. “I don’t want people to greenwash, of course, but the result is that there is a timidness now in sustainability plays, and that is hurting causes,” she says. “People want results, and I think there is a lack of people seeing best practice and how it can be done.”

As it turns out, McLaren would view it differently. Instead, the British racing team noted the similarities in the two organisations’ processes and viewed the issue as a problem to help solve – and as Mardsen points out – one that could help pave the way for others to follow via a path of innovation and proof-of-concept.

For context, McLaren Racing has its own climate contribution programme, which is part of the company’s goal of achieving net zero by 2040. But it also has a lesser-known sector called McLaren Accelerator, a crack team of bright minds and in-house experts that repurpose their on-track and performance engineering know-how and learnings to a range of wider applications. McLaren has the most partners of any racing team, so its reach spans multiple industries, from sport to tech to wider industrial applications. As unlikely as it might seem, McLaren and the Great Barrier Reef Foundation figured out they operate in similar ways.

“We understand that it could be [seen as] strange,” Piastri tells me of the partnership. “Even for me, when I was learning [about it all], the parallels in our working environments and the mindsets are incredible in terms of how similar they are.” The 23-year-old driver points out that in Formula 1, teams work hard to continuously optimise and evolve the car, in pursuit of speed and with cost efficiency (and budget caps) front of mind. He noticed that within the non-profit organisations, this was a similar situation.

“For me, the objective of the Great Barrier Reef Foundation is along similar lines: trying to grow the best corals they can, that are going to be resistant to the changing world, as many of them as possible, as quickly as possible and in the most cost-efficient manner.”

He adds, “So whilst it’s a very different topic, the same principles very much apply. And I think that’s where McLaren can help to try and boost the project and add value to it by extending our values in racing, and the methodologies and technologies that we use, into a very different project that will ultimately leave the world in a better place, which I think is a great thing.”

You may be wondering by now how McLaren came to work with the foundation. Well, speaking to the grassroots nature of the British company, the partnership all started with cable ties. “One of the team members was watching a documentary on the Great Barrier Reef one evening and he came to me and said I should talk to them and the guys in the racing team’s supply chain team,” Kim Wilson, McLaren’s sustainability director, tells us.

“He’d emailed them because he had been concerned about cable ties being used to attach coral fragments onto frames – he wanted to know if they were biodegradable and if so, did they have a good supplier because maybe we could use them?”

Turns out, the cable ties being used were from a different reef – and for the record, mortified the Australian non-profit – but the conversation sparked a wider one around data, supply chain and engineering – and the conversation went from cable ties to a full-blown knowledge sharing programme.

McLaren offered up its engineers and technical experts to take a look at the foundation’s coral production line-of-sorts and optimise how it could be sped up and automated for a better result and survivability. Just like we see on the track, the partnership is an ongoing consideration of how data can be used better, based on whatever goal the foundation is trying to achieve.

“As a driver, you have a natural instinctive way of driving, and I guess, a natural talent in some aspects. But without data, I don’t think any of us would be the drivers we are today,” Piastri notes. “For us, there are a lot of changes we make on the car, where we end up just trusting the data and trusting the numbers that it’s going to be faster.”

Data that is fast and digestible is important, he says, but ensuring accuracy is even more so. In practice, racing cars and growing corals, aren’t that dissimilar. “Corals do whatever the hell they want,” Cedric Robillot, executive director of the Great Barrier Reef Foundation, and who helps lead R&D, quips in response to Piastri talking about data and car setups ahead of a race. “You make a change and you can have no idea – the full moon was too bright or whatever,” he laughs.

“To be honest, it can be the same for us,” says Piastri. “Especially overnight, like from FP2 to FP3. Or if we have a night race, for example, like Abu Dhabi, where we have FP1 in the middle of the day when the track is 50 degrees and FP2 when it’s 25. You change a whole bunch of stuff on the car and you’ve got no idea if it’s because the track has less dust on it, whether it’s colder weather, if its because you’re driving better or because the car is actually better.”

He adds, “You’ve got all of those different factors that you can’t always know. So you end up just having to trust the numbers are going to be right.” It’s this mentality that the team have applied to the work with the reef.

Beyond the assisted growth and survival of baby corals and the reef, the partnership highlights two things. One: how companies with diverse backgrounds can look at their processes and consider how they might actively help to move sustainability projects along. And two: how elite athletes, particularly those with young and passionate fanbases, like Piastri, can rotate their gaze towards supporting the world in which they travel so extensively – not unlike how Lewis Hamilton and Sebastian Vettel have used their platforms.

But remember, this is only Piastri’s second year in F1. “In my first year, in Formula 1, I was incredibly focused on on trying to establish my career,” says Piastri. “I am still putting an incredible amount of effort into doing that. But I think for me, other topics outside of Formula 1 and motorsport are important. As you know, Lewis [Hamilton] and Seb [Vettel] have been champions of various topics outside of the sport, so I feel like, with time, I’ll grow into that more and more,” he says.

“I think also there is sort of a growing, let’s say, onus on athletes, in general, to be able to speak about more than just what they do on the track . . . For me, this one in particular, is quite close to home, because it is home. And, I think it would be a genuine shame for, not even generations to come, but current generations, to not be able to see one of the most beautiful parts of Australia.”

Related:

Oscar Piastri claims his first ever Grand Prix victory

The Road Trip: through Victoria’s Yarra Valley in a McLaren Artura