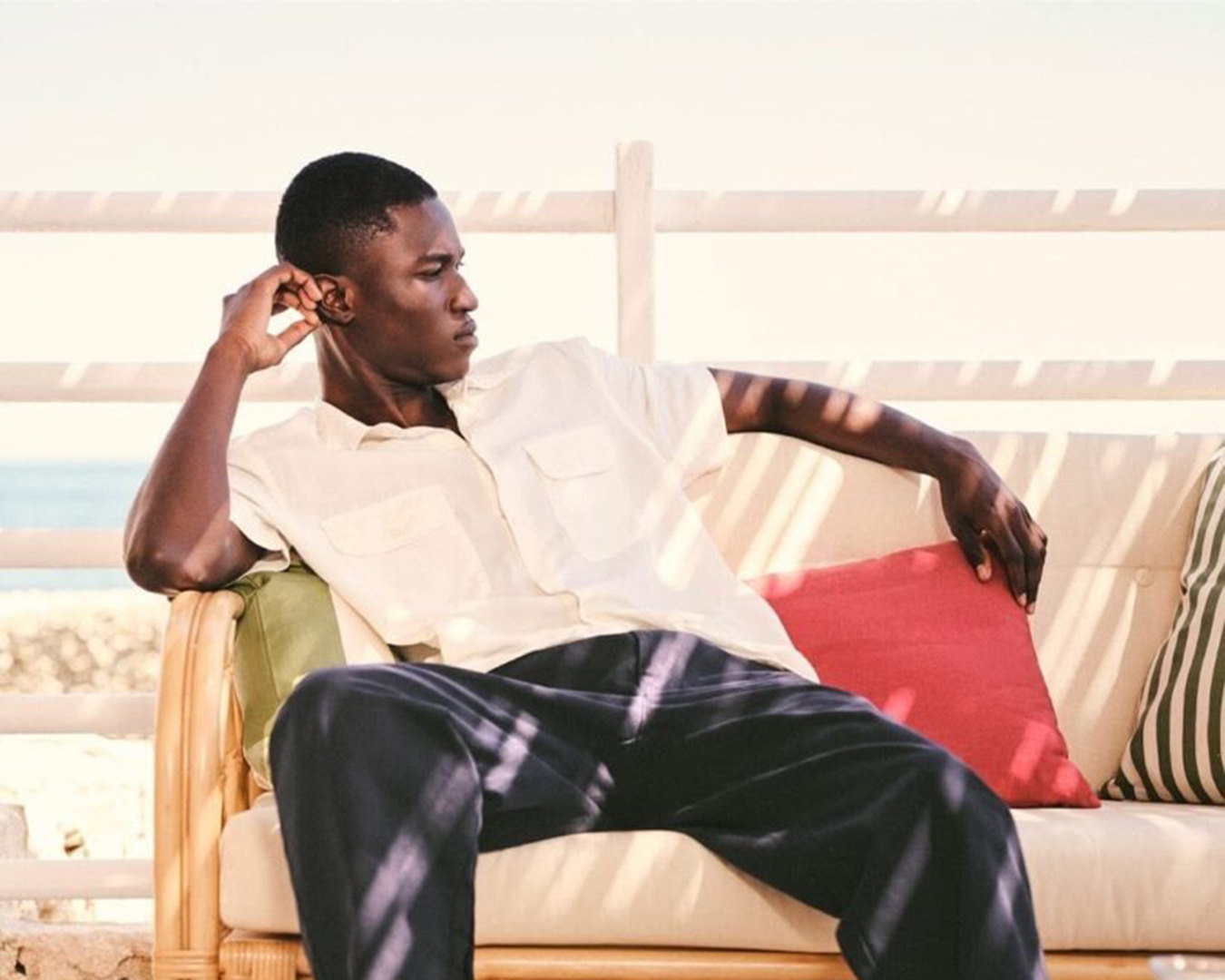

How Perth brand Man-tle built a global cult following around craft

At Man-tle, designers Larz Harry and Aida Kim are pushing a more deliberate, craft-led approach to menswear, earning them customers who like tough clothes that will last forever

I HAVE A SHIRT from Man-tle that sits as though it’s floating on my body. The cut is generous, its armholes deep, and there’s enough room in the sleeves and chest that when I hold my arms up, it inflates with air. But the shirt’s fabric was the biggest revelation: a densely woven cotton designed to crease into a papery texture with time and wear. At first, it was so stiff that I had the childish urge to ball it up and throw it in the air, eager to speed up its patina. In other words, it made me realise – and appreciate – this was a piece of clothing that would grow and change with me. It demanded I wear it in.

Larz Harry and Aida Kim, the husband-and-wife duo behind the brand, have been encouraging this attitude of ‘wearing in’ your clothes since they launched Man-tle in 2015. It’s an ethos at odds with fast fashion, a school of thought that’s changing the way we think about how well-made clothes are supposed to look, feel and behave.

“We’ve always tried to make a product that sits outside fashion but has a timeless character to it. We try to make clothes that last a long time,” says Harry, who, with Kim, is talking to me from their industrial- designed studio-slash-store in Northbridge, just outside Perth’s city centre. This mode of thinking, for Kim, started with her father, who kept a rotation of thick knits, leather, denim and hard Oxford shirts. “He liked really strong fabrics,” she recalls. “I liked watching the garment evolve with time. It became more beautiful . . . it became like a part of him.”

The pair met while working in Tokyo. Kim was a brand director at Black Comme des Garçons, working directly with its founder, Rei Kawakubo, while Harry worked in marketing and communications at Dover Street Market, the concept store created by Kawakubo and her husband, Adrian Joffe. While immersed in these avant-garde worlds, their desire for more practical and durable forms began to percolate. “The move from what we were working with then, to what we do now, was a pretty conscious one,” recalls Harry. “From that experience, it was important to have an original point of view.”

After leaving the company and deciding to start their own, the two drove around Japan in a rental car, courting mills and factories that could help them develop original fabrics. It was one introduction after another, often by an artisan who knew someone who specialised in the thick weave or specific dye Man-tle needed. After establishing their network, the two moved to Harry’s hometown of Perth to continue their new project away from the noise of Tokyo.

“The main work that we do as a brand is designing product,” says Kim, referring to their desire to create pieces outside of the fashion system. “To do that, we have to be here because our lifestyle is really important to us . . . it’s reflected in the garments. If we put ourselves in a big city, I don’t think we could design what we are designing right now.”

When designing collections, the pair look to the arid landscape that stretches out around them. The cut of my particular shirt, Harry explains, allows for ventilation in the dry West Australian heat. Colour, too, is derived from nature: dry eucalypt green and ochre as if swatched from the earth itself. It’s the strength of the sunlight here that Kim, who grew up in South Korea, is perpetually fascinated by. Their work presents a different idea of contemporary Australian menswear, one that’s connected to the land, rather than visions of a far-flung European summer. They’ve captured a global fanbase with pieces offering armour-like assurance, or what many menswear commentators have labelled ‘hard clothes’. But really, their desire to create clothes that are beautiful in a trend-less way, speaks louder. Working here, on what feels like the periphery of multiple major fashion markets, Man-tle has thrived.

Yet Perth is the only city in Australia with a direct flight path to Paris. This makes the couple’s biannual trips to the city for Men’s Fashion Week – where they’ve been hauling suitcases filled with their collections to show in a Marais gallery space since 2017 – a bit easier. Hosting international buyers for wholesale appointments, it’s the only extracurricular sales activity Man-tle partakes in. Outside of Perth, Man-tle has no other presence in Australia (though the brand is stocked at a select handful of niche menswear stores throughout Japan, North America and Europe, global outposts that resonate with Man-tle’s thoughtful ethos).

When Louis Cheslaw, a writer and the menswear columnist for Magasin, visited Man-tle’s Paris showroom in June, it was the first time he was able to feel its signature wax cotton. Like many of the brand’s loyal customers, Cheslaw admits to “nerding out” about the dying process – pieces get their pigment from natural elements like mud and mangosteen. “Prices for some designers are incredibly high right now, without much of a sense of why,” Cheslaw says. “Whereas with designers like Man-tle, those narrative details – about the process and the rarity of the fabrics used – help justify what is still a real expense.”

“For the garment to reflect that it’s made by people’s hands is something we’ve never tried to hide,” says Harry. He’s talking about how, if a piece of dust gets caught in a loom, it leaves a tiny grey line in the fabric. Rather than rejecting such an imperfection, Harry and Kim find it charming. To them, knowing where things come from – seeing evidence of a human hand – is the ultimate signifier of craft. “We would love to communicate this to our customers, that these little things are not problems.”

“To us, ‘craft’ doesn’t mean it’s a ‘perfect’ garment,” adds Kim. “It’s more about everyone’s pride in the process, and we hope the customer can feel that through the garment.”

Adds Harry: “Why would you want it made any other way?”

This story originally appeared in Esquire Australia’s November/December 2024 issue.

Related: