What happens when fashion, entertainment and culture collide?

Menswear is becoming increasingly intertwined with celebrity, entertainment and sport. Does this mark the end of an era, or the start of an exciting new chapter?

“LOUIS VUITTON, PHARRELL WILLIAMS and the loss of fashion magic.” Robin Givhan, one of the world’s most esteemed fashion critics, didn’t water down her feelings towards the biggest appointment in fashion this year, and possibly this decade—maybe even longer.

“It serves as another blow to the belief that fashion design is a skill and not merely an attitude,” she wrote for The Washington Post of Louis Vuitton’s decision to hire a celebrity with no formal fashion design training to lead its menswear business. “But okay. Fine. Life is not fair.”

If you have been following the discussion surrounding Pharrell’s appointment at Louis Vuitton, you’ll be aware that Givhan is not alone in her view. From fashion schools to the studios of independent designers all over the world, you’ll be hard-pressed to find a fashion purist who is thrilled by the prospect of a multi-hyphenate musician, however iconic Pharrell may be, calling the shots at the world’s most influential fashion house—in 2022, Louis Vuitton became the world’s first €20 billion ($33 billion AUD) luxury brand. As someone who writes for traditional fashion media—a corner of the industry with its fair share of purists—I get the point of view, however cynical it may seem. Watching Pharrell get the job over highly skilled designers is a bit like being smoked by the runner who didn’t train for the race you’ve spent your entire life preparing for.

But perhaps this is missing the point. After all, with strong ties to the worlds of sport and art, it’s becoming increasingly clear that Louis Vuitton isn’t just a luxury fashion brand, but a booming cultural entity—football superstars Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo starred in a campaign ahead of the 2022 World Cup, while Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama is a longtime collaborator. Depending on who you talk to, therefore, Pharrell’s appointment represents either the writing on the wall for trained designers, or an exciting shift in a notoriously exclusive industry.

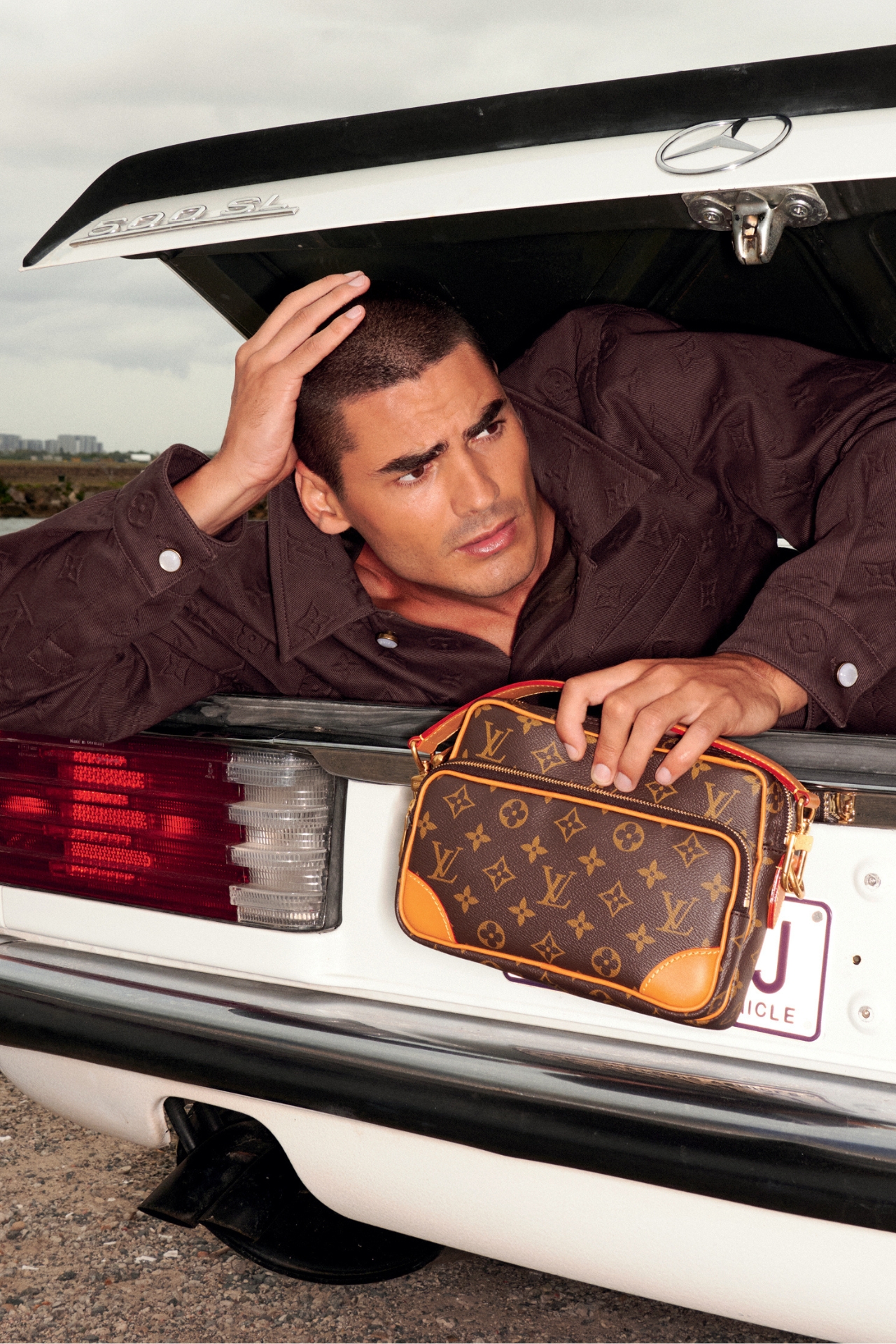

A jacket from Pharrell’s Louis Vuitton collection. COURTESY OF LOUIS VUITTON

First, a recap: following the sudden passing of Virgil Abloh in November 2021, who was the head of Louis Vuitton menswear from 2018 until his death, Pharrell Williams was named the new creative director of the brand’s menswear business in February 2023. The appointment followed years of speculation; it was something of an open secret that critically acclaimed independent designers Grace Wales Bonner and Martine Rose were front runners for the job. But while the industry spun these rumours, Pietro Beccari, a longtime LVMH executive who became the chairman and chief executive of Louis Vuitton in January, had someone entirely different in mind: Pharrell.

In multiple interviews, Beccari has given justifications to the tune of: “After Virgil, I couldn’t choose a classical designer… It was important that we found someone [that has] a broader spectrum,” he told The New York Times. “I thought we needed something more. Something that went beyond just pure design.” Plus, it wasn’t like the ‘Happy’ singer had no ties to fashion—in addition to his reputation as one of music’s most stylish men, Pharrell co-founded streetwear brand Billionaire Boys Club with Japanese fashion icon Nigo in 2003; he’s also collaborated with Chanel on numerous occasions and, in 2004, he worked with Marc Jacobs, the then-creative director of Louis Vuitton and first designer of the brands ready-to-wear line, on a pair of iced out sunglasses called the ‘Millionaires’. (Fun fact: he was also voted the “Best Dressed Man in the World” by US Esquire in 2005).

Pharrell presented his first menswear collection for Louis Vuitton in June. Held on Paris’ Pont Neuf bridge, the spectacle was attended by the world’s most famous people—among them, Beyonce, Lewis Hamilton, Kim Kardashian, Riz Ahmed and Rhianna, who was the star of Pharrell’s first campaign for the brand. Jay-Z performed live after the runway, and the show was met with largely positive reviews, not only for the clothing but, perhaps more importantly, the ‘moment’ it represented. After Abloh, Pharrell is the second Black man to lead Louis Vuitton menswear. And crucially (like Abloh), Pharrell is someone who speaks to the modern ideals of luxury. Today, luxury fashion isn’t just about clothes. It’s about capturing the collective imagination through the use of imagery, personalities, clever collaborations with other pillars of popular culture and, somewhere down the line, clothing.

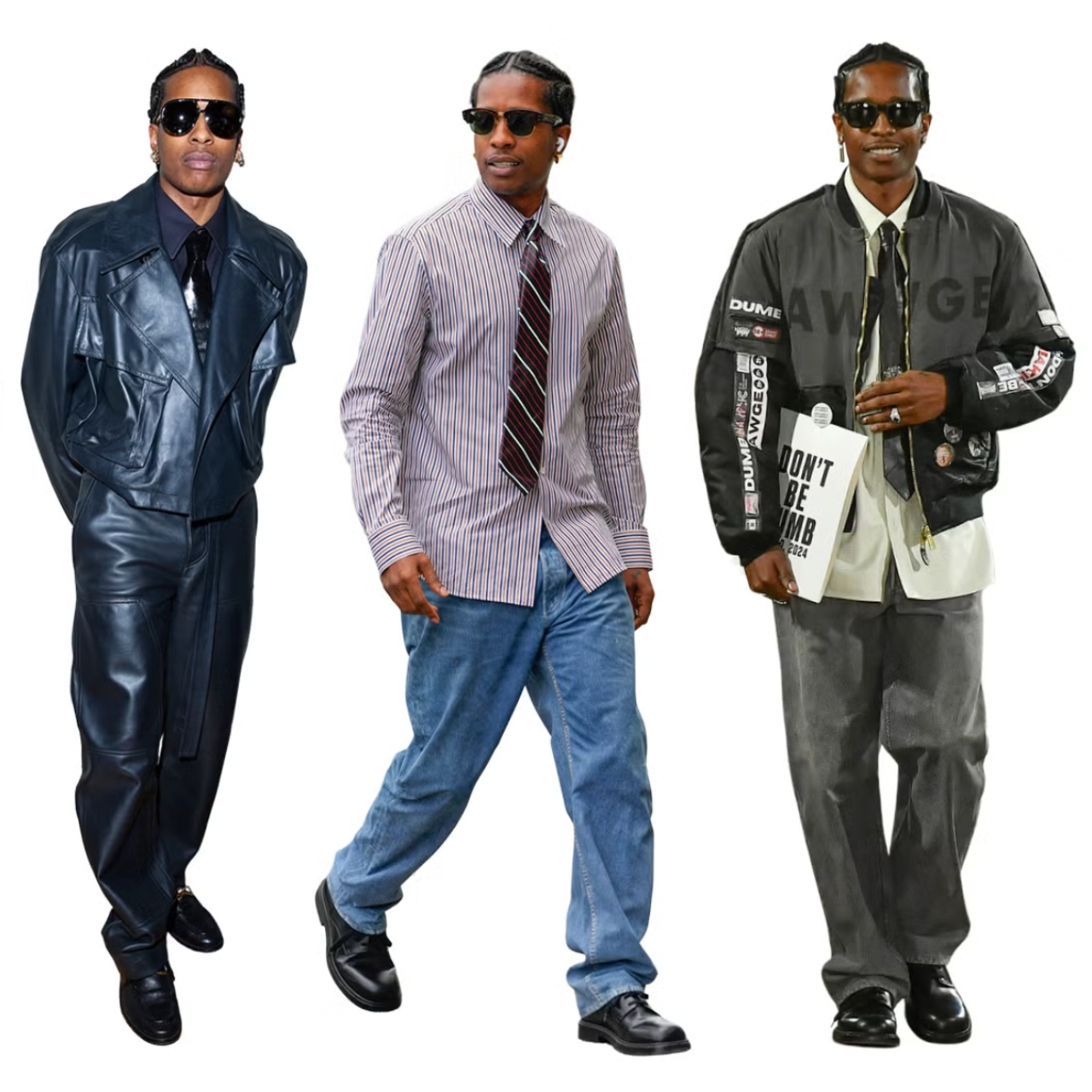

Celebrities at the most recent spring/summer 2024 menswear shows. GETTY

Positioning fashion this way—as a form of popular culture—is becoming an especially effective way to market menswear. Guys are much more likely to be influenced by sports stars and musicians than they are fashion designers in ivory towers. Esquire’s recent interview with Kim Jones, artistic director at Dior Men’s, says it all. “Fashion’s really great and I love working with it, but I think nowadays you need a bit more than that,” says Jones. “I’m much more into culture than fashion in terms of the way things reach people.” And when it comes to reaching people and capturing our imaginations while making dollars, the buck stops with the creative director.

“THERE ARE PRECEDENTS to a lot of this says Rosie Findlay, a London-based fashion researcher and media academic who currently lectures at City, University of London. “A creative director or head designer playing a really big part in branding and image-making at a house has a longer history than we might think it does. It’s just that things have shifted to such a degree now that more people are talking about it.”

Findlay, who goes by @fashademic on X considers Karl Lagerfeld to be the blueprint of the modern creative director. “He was really patient zero,” she says. When Lagerfeld entered Fendi in the ’60s, it was a stuffy fur house known only for its exorbitantly priced coats. Yet by introducing more accessible items made from less-expensive skins, like gloves and hats, he revamped the house’s identity. “In a sense, he set the precedent for what a head designer could do,” adds Findlay.

Karl Lagerfeld (left) and Yves Saint Laurent (middle) with models at the International Wool Secretariat in 1954. COURTESY OF WOOLMARK

It was Lagerfeld’s designs that revamped the brand, but they were successful because they responded to the social moment in which they existed. Over time, this ability to intuit cultural trends—and craft products in dialogue with them—became the marker of a successful fashion designer. Yves Saint Laurent did it with ‘Le Smoking Tuxedo’ in the ’60s; Roy ‘Halston’ Frowick with the halter dress in the ’70s; Alexander McQueen with ‘Bumsters’ in the ’90s and so on. But as time went on and fashion became more of a business, crafting a single product that spoke to the zeitgeist wasn’t enough; the entire brand had to resonate.

In the late ’90s, plucking talented young designers from relative obscurity and giving them permission to breathe new life into legacy brands was becoming more common. In ’96, when McQueen was hired by Givenchy and John Galliano was given the top job at Dior, the pressure these designers were under to reimagine these brands was extreme.

In Gods and Kings: The Rise and Fall of Alexander McQueen and John Galliano, veteran American fashion journalist Dana Thomas observes of the era: “It became obvious to me that the balance between art and commerce was out of whack… They[McQueen and Galliano] were part of a magical moment in fashion, and their endings came at a time when this disconnect was at its most profound.”

In the early 2000s, commerce dug its claws even further into the fabric of the fashion industry. And so this pressure to transform brands into culturally relevant moneymakers became the norm. It also cracked open the door for designers with skillsets beyond sewing and sketching to enter the industry and succeed. Findlay points to Hedi Slimane at Dior Homme as a prime example of this new-age fashion creative. “He was a photographer as well as a designer, and so all this different media he consumed informed his reimagining of this very androgynous, slim ‘poet rocker’ archetype of masculinity, which was hugely influential through fashion at the time,” notes the academic.

“If you’re appointing a creative director today, I think a big part of the concern would be: can this person kind of lick their finger and put it to the wind to see what’s happening?” Up until now, the most evolved example of this cultural pulse-taker was Virgil Abloh. If Karl Lagerfeld was the blueprint for the 20th century creative director, and Hedi Slimane that of the Tumblr generation, Abloh was the archetypal creative director for the digital age. But his appointment at Vuitton was also polarising. Despite running his own wildly successful streetwear brand, Off-White, he had no formal fashion design training. Nevertheless, he understood the power of visuals—arguably the greatest currency of the social media age—and had a savant-like ability to bring important people together, and use his platform to amplify their voices. “The community he created through his practice, while having conversations collectively through Off-White and Louis Vuitton, was really quite amazing,” remarks Findlay. And while Abloh’s designs sold well, this will remain his defining legacy.

Of course, this was always going to be a hard act to follow. And it’s through the lens of what Abloh started that Pharrell’s appointment makes the most sense. But this succession of ‘non-designers’ leading the world’s biggest menswear brand brings us back to the ‘blow’ Givhan writes of, which could also be viewed as an affront to those who’ve spent years toiling away at fashion school. When it comes to scoring the top job, is celebrity now more important than skill?

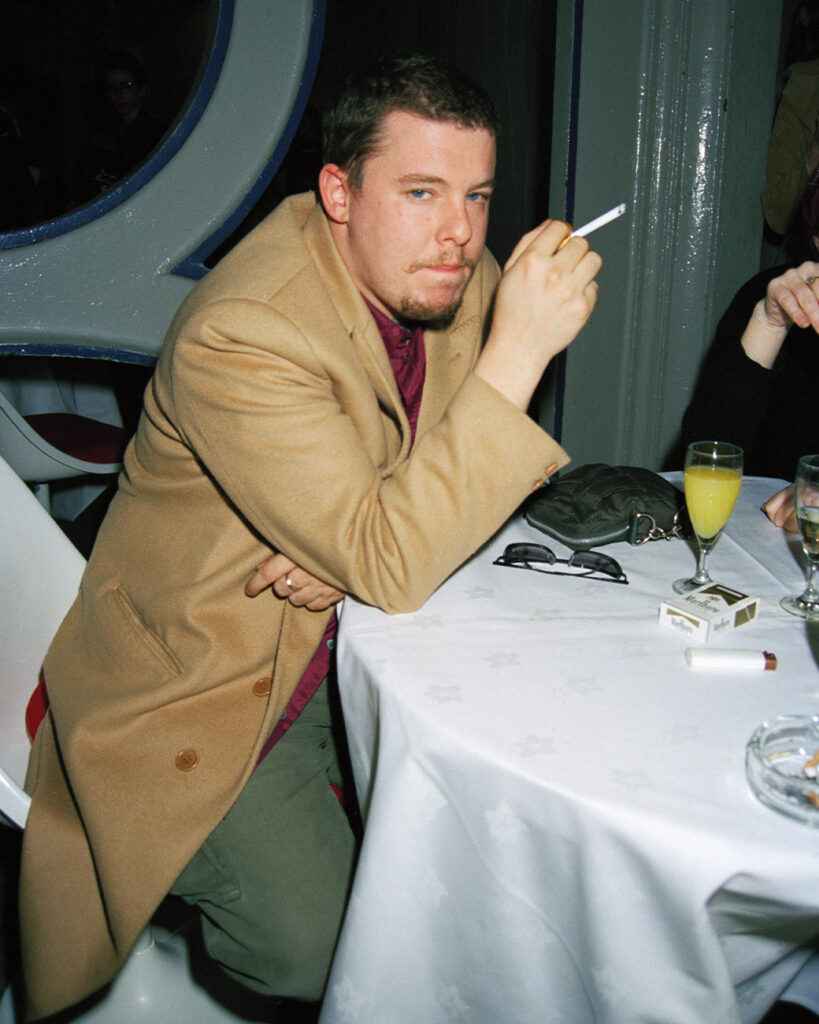

Virgil Abloh at the Off-White show in Paris in 2016. GETTY

“WHEN I WAS YOUNGER, it was really my dream to be the creative director of another brand,” says designer Alix Higgins, who launched his eponymous brand in 2021. “It is still a dream of mine, but it just feels like the days of hiring a young, fresh designer—even someone who is super talented and famous within their own niche—are gone.”

In addition to being one of Australia’s most visionary young designers—his internet- inspired pieces have been worn by Euphoria actress Hunter Schafer and singer Grimes— Higgins teaches fashion students at the University of Technology in Sydney, and he’s also worked in Paris under the high priestess of luxury up-cycling, Marine Serre. He has

somewhat of a vested interest in the conversation, as a young designer with a fast growing brand and big ambitions.

“It makes sense—who could follow Virgil but a superstar like Pharrell? When you have someone as famous as Virgil running the show, and millions of people are listening, you need someone with an extremely huge audience to follow.”

Findlay also emphasises the emergence of luxury conglomerates as playing a key role in the evolution of fashion, and therefore the evolution of the creative director. “Conglomerates are big businesses, and big businesses need to make a profit. So you’re trying to capture people’s attention. You’re trying to make people feel something while gathering the most followers without alienating long-term customers. Luxury fashion is big business now, and that’s been an enormous transformation.”

Another enormous transformation that plays a not insubstantial role in this conversation is celebrity. Where once, fashion shows were intimate events held behind closed doors in private ateliers, the presence of very famous faces at runways today has meant more people than ever care about the spectacle, which is made readily accessible through Instagram and TikTok.

Pharrell Williams. GETTY

Pharrell’s debut show for Louis Vuitton, its men’s spring/summer 2024 collection, has been viewed an eye-watering 15 million times on YouTube since it went live on June 21. Needless to say, fans of Pharrell have played a big role in nudging that number north.

Which brings us to the large group of people who are excited to see a guy like Pharrell leading Louis Vuitton. They are hip-hop heads who still listen to The Neptunes; guys who bought their first ‘fashion’ piece from Billionaire Boys Club; kids that grew up listening to the soundtrack of Despicable Me (Pharrell served as the film’s composer). If Pharrell is to fill the shoes of his predecessor, and meet expectations as a modern creative director, he’ll do it by bringing fashion to a more diverse audience of people—fans who may not be able to afford an LV bag, but who absolutely want in on the action.

“I remember listening to Clipse’s album Hell Hath No Fury as a teenager and being blown away by Pharrell’s production on it,” says Christopher Kevin Au, a music journalist and A&R at Warner Music Australia. “Then to see both members of Clipse walking down the runway at Pharrell’s first Louis Vuitton show… There aren’t many people in the world with such a long-standing reach into so many creative and subcultural lanes, who can create iconic moments like this.”

To create iconic moments that resonate on a global scale; to capture the imagination of fans, not just customers—is what being a creative director today really boils down to. But must you be a bona fide celebrity to get the job done? Look at what Alessandro Michele did at Gucci, and what Jonathan Anderson is doing at Loewe—two formally trained designers with a track record of blending fashion moments with popular culture.

The celebrity creative director, you could argue, isn’t necessary for every luxury brand. But to sustain the scale of Louis Vuitton, a company that views itself not as a fashion brand, but a cultural powerhouse? It’s a pretty savvy move.

Related:

Pharrell Williams consolidates Louis Vuitton — and luxury fashion’s — new groove

Dior, Kim Jones and the art of cosmic couture

Carlos Alcaraz brings the smooth in his first Louis Vuitton campaign