The politics, price, and power of protests in 2025

Protest has always been a tool of resistance. But in 2025, its costs are rising. With new laws and social backlash reshaping who gets to dissent and how, Esquire asks: what is the real power – and price – of standing up?

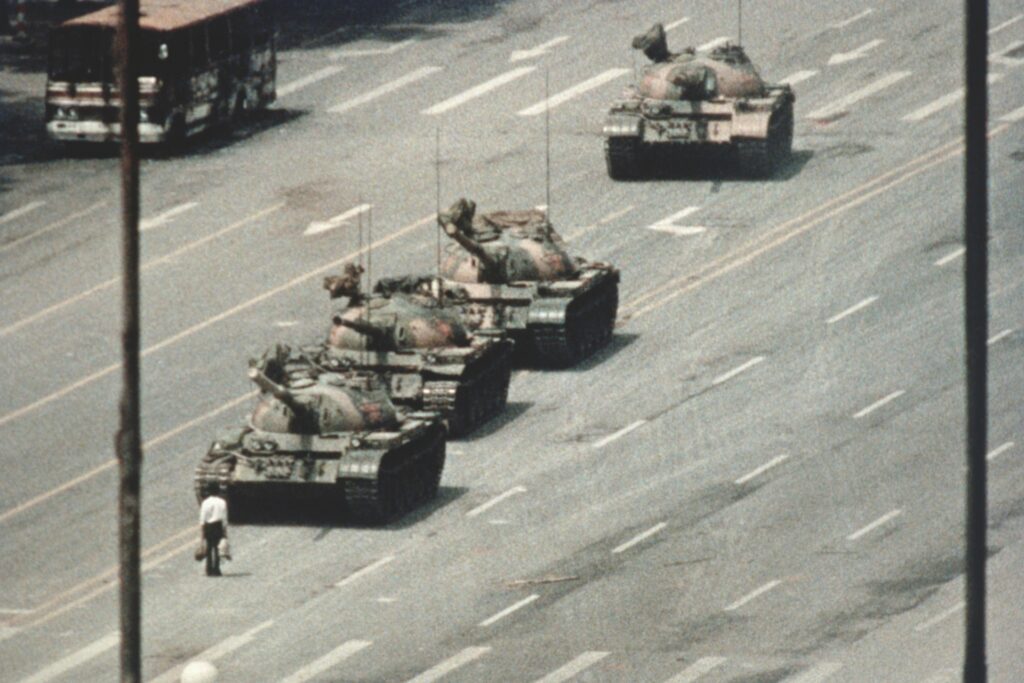

ON A SUNNY DAY IN 2016, 77 women – each pulling a small suitcase – walked in silence towards the Irish embassy in London to protest Ireland’s Eighth Amendment, a constitutional clause equating the life of the unborn with that of the mother, effectively prohibiting abortion (unless the mother’s life is in immediate danger). Twenty-seven years earlier, a lone protester known only as Tank Man stepped into the path of a column of armoured vehicles leaving Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, one day after thousands of pro-democracy demonstrators were massacred by the state.

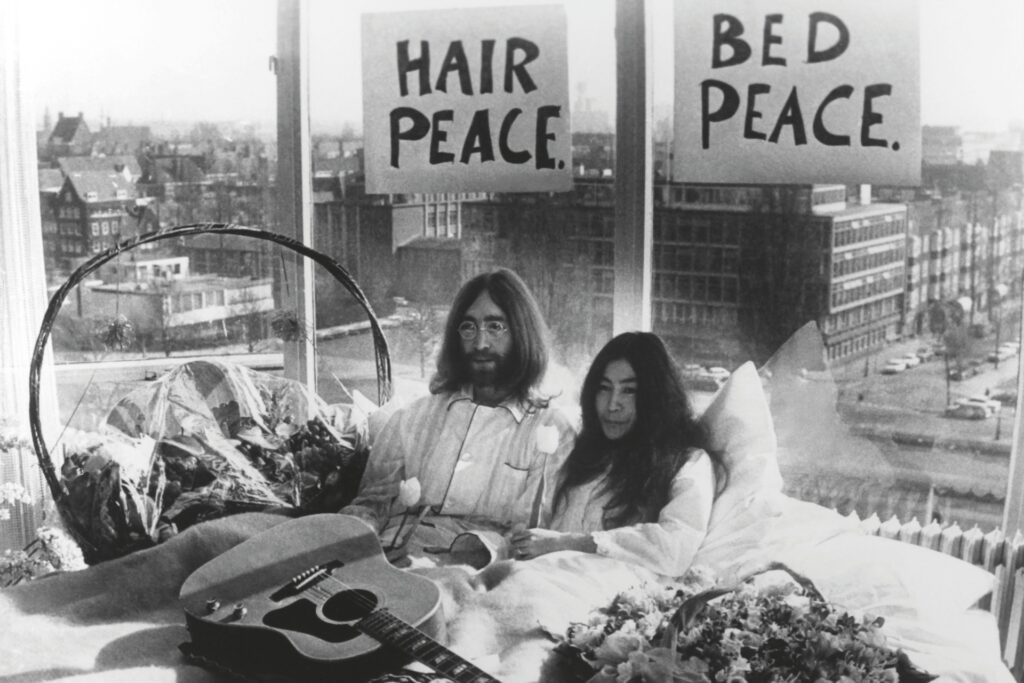

In 2012, eight members of the feminist punk band Pussy Riot mounted a platform in Moscow’s Red Square to perform their song “Putin Zassal” (“Putin Has Pissed Himself”) in the wake of anti-Putin rallies. And in 1969, John Lennon and Yoko Ono invited the world’s media into their Amsterdam honeymoon suite for a weeklong “Bed-in for Peace”, protesting the Vietnam War by, as the name suggests, refusing to get out of bed. These acts – solemn, absurd, iconic, anonymous – aren’t mirrors in scale or shape. But they’re bound by an instinct: a desire to be seen and heard. A calling to protest.

‘Protest’ – from the Latin pro testari (to bear public witness) – exceeds objection. As cultural theorist Raymond Williams wrote in his 1976 book Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society, it is to “stand as a public witness to injustice”. And from the first recorded labour strike in 12th century BCE Egypt to the 100,000-strong march for Palestine across the Sydney Harbour Bridge – taking place at time of writing on a sodden Sunday in early August – the determination to challenge power through protest is a response as old as humanity itself.

But if protest is instinctual, so too is the backlash. In 2025, the response from a subset of those in power has intensified, courtesy of harsher laws, surveillance, police overreach and asset seizures. “This is something that’s been happening since time began,” says David Mejia-Canales, a senior lawyer at the Human Rights Law Centre in Melbourne. “[Protestors] are trying to hold the powerful accountable, and the power will always react in some way.”

In the popular imagination, protest is the messy, oftentimes inconvenient proof of a healthy democracy. The reality is more complicated. “The protection for the right to protest has always been very, very patchy,” says Mejia-Canales. Unlike countries with constitutional guarantees, Australia has no explicit legal right to protest, but rather an implied freedom of political communication, which governments can restrict if they deem the response to be reasonable and proportionate. “What we’re seeing, particularly in the last 20 years, is a very steady erosion of the right to protest by using the criminal law as a weapon,” he says.

In the past few years alone, Australian states have introduced or expanded laws that criminalise basic protest actions. In 2023, South Australia passed a bill that increased the maximum penalty for obstructing a public place from $750 to $50,000, or up to three months in prison. In NSW, climate protestor Deanna ‘Violet’ Coco was sentenced to 15 months in prison (later overturned on appeal) for blocking one lane of traffic on the Sydney Harbour Bridge for 25 minutes.

This past June, the question of reasonable police intervention re-entered the spotlight after former Greens candidate Hannah Thomas was allegedly punched by a NSW police officer during a pro-Palestinian protest in southwest Sydney. After reportedly failing to comply with a move-on order, Thomas sustained a serious eye injury that required multiple surgeries. Her solicitor, Stewart O’Connell, has confirmed she will sue the state of NSW “for the actions of the NSW police officers connected to her apprehension, injury, detention and prosecution”.

Of the protest landscape in 2025, the NSW Police’s media unit stated via email that the “NSW Police Force recognises and supports the rights of individuals and groups to exercise their rights of free speech and peaceful assembly”. It continues: “The priority for NSW Police is always the safety of the wider community and any unlawful activity will not be tolerated.”

Mejia-Canales believes that the consequences of protest aren’t solely about prosecution – they’re about pre-emptive suppression. Protestors are routinely handed bail conditions that prohibit associating with one another, attending further protests or entering the CBD, for example. “[Law enforcement] do that to break up the protest movement,” he says. “They go for the organisers, and then they pull apart the movement, and then the energy in that movement disappears.”

Sometimes, the challenge comes not only from police or legislation, but from the language leaders use to diminish or reframe dissent. In March 2021, after a series of high-profile sexual assault and harassment allegations in Australian politics, tens of thousands of people – overwhelmingly women – joined March4Justice rallies nationwide, demanding action on gendered violence. Addressing Parliament that day, Prime Minister Scott Morrison acknowledged the right to protest before adding: “Not far from here, such marches, even now, are being met with bullets – but not here in this country”. Pitched as a nod to Australia’s freedoms, the remark was read by critics as a minimisation of the protesters’ grievances, implying gratitude for safety rather than urgency for change. A subtle rebuke of sorts, framing protest not as a democratic right but as a privilege that could be withdrawn.

It’s not a new dynamic. As Mejia-Canales points out, the suffragettes were brutalised and imprisoned. The first Mardi Gras marchers were arrested en masse. And, as always, hindsight is 20-20. “We look back at the people who were protesting the war in Vietnam, and we’re like, ‘Yeah, absolutely. That was so right.’ But we can only say that now. Protesters are always right in history books, but they’re never right in today’s headlines.”

Which is why today’s headlines matter. Tarneen Onus Browne – a Gunditjmara, Bindal, Yorta Yorta, Erub and Mer Islands writer and organiser with Warriors of the Aboriginal Resistance – recalls the intense backlash following Melbourne’s 2020 Black Lives Matter rally, organised in just five days to protest the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis and Aboriginal deaths in custody. The personal cost was steep: media vilification, fines for breaching COVID-19 orders (later dropped) and, after the 100,000-person rally, a wave of death threats. “I dyed my hair blonde because I was terrified and didn’t want to be recognisable on the street,” they say. “I just was worried about people wanting to hurt me.” For First Nations organisers, Onus Browne says, the stakes are always higher, amplified by a deep-seated hatred too often underestimated.

Onus Browne’s experience speaks to a larger truth about collective activism: protest is never just about the message. It’s about who delivers it and, increasingly, where it happens. And as with most public expressions, the mediums have shifted. Remember Kony 2012 (it feels like yesterday, doesn’t it?), the short film about Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony? In many ways, the campaign was a turning point in digital organising – a blueprint for modern ‘awareness’ activism – but it also signalled a new kind of visibility. While its impact was muddied by factual inaccuracies and the public breakdown of its creator, Jason Russell, the campaign proved that online mobilisation could reach millions in days.

Today, the risks of online expression are far more potent. In the US, travellers have been denied entry based on memes or messages on their phones that are deemed to be critical of President Trump. Mejia-Canales, who recently travelled to the US, considered bringing a burner phone. “I’m a very, very brown Latino person, and going through the US for me, as a human rights lawyer with all this sort of . . . I don’t have memes on my phone, but I certainly have a lot of privileged information that I don’t want the US authorities to see. It was terrifying for me,” he says.

That fear isn’t unwarranted. ICE raids, police surveillance of protest organisers and deportation threats are all on the rise in the US, and concern about the impact on Australian human rights principles swells in unison. “I fear that this will embolden people who don’t have our best interests at heart to act in the same way here, because it feels possible,” says Mejia-Canales. “It’s not even just possible; it’s happening right now.”

If the price of admission for advocacy is creeping higher, why are people still paying it? For Sydney-based activist Zack Schofield, protest is less a choice than a moral obligation. “I’m really privileged in many ways, and I want to use that privilege as fully as I possibly can,” he says. As an organiser with Rising Tide, a grassroots climate group targeting the coal industry in Newcastle, Schofield has helped lead two blockades of the world’s largest coal port, the most recent drawing more than 7000 participants in November last year. He talks about the extreme heat and natural disasters people around the world will experience, concurrent with the pressures of supporting a family and keeping a roof above their heads. “For those people, I feel like it’s a duty to be as effective an organiser as possible.”

The work is also a source of joy for Schofield. “It’s the people that we’re organising with. The strongest, the deepest, the best relationships in my life have been forged through sharing a common purpose.”

Protest endures, not because it’s easy but because it insists on possibility. And because sometimes, the needle does move. Onus Browne says that, five years on, the effects of the BLM marches are still unfolding. “One of them was the Victorian government really seeing the importance of truth telling,” leading to the Yoorrook Justice Commission – Australia’s first formal inquiry into systemic injustices against First Peoples.

Schofield has been wrestling lately with something he calls “terrible optimism”. “Optimism is terrible for the optimistic because it requires you to take action. If you think that it’s possible to change the world, then you are called to pitch in.” But it’s also terrible for those who don’t like to be challenged for power. Because, deep down, they know that those who are wired to call out injustice will never go quietly.

This story appears in the September/October 2025 issue of Esquire Australia, on sale now. Find out where to buy the issue here.

Related:

The artist behind the “AUSSIE” poster is about to put up more