“If the gap is to be closed, we must get to know each other better”

It’s been four months since the Indigenous Voice to Parliament referendum was defeated. With January 26 upon us, in an essay for Esquire, Kaurareg Aboriginal and Kalkalgal, Erubamle Torres Strait Islander activist and author Thomas Mayo writes about why a greater familiarity and understanding between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples is key to ending entrenched inequalities in this country.

“We are a much unloved people. We are perhaps the ethnic group Australians feel least connected to.

– Noel Pearson, 2022 Boyer Lecture.

We are not popular and we are not personally known to many Australians. Few have met us and a small minority count us as friends. And despite never having met any of us and knowing very little about us other than what is in the media and what WEH Stanner, whose 1968 Boyer Lectures looms large over my lectures, called ‘folklore’ about us – Australians hold and express strong views about us, the great proportion of which is negative and unfriendly.

It has ever been thus. Worse in the past but still true today.”

INDIGENOUS LEADER Noel Pearson’s description of how non-Indigenous Australians relate to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people rang true this past year. He foretold of the difficulty we would face with the referendum; the challenging task of convincing a people who do not know us, and who are easily led to think the worst about us, to accept our rightful place in this country. In the wake of the referendum, and with January 26 upon us, versions of the same question have been posed by many of us: how can we possibly have hope when the hand of friendship continues to be slapped away?

In early 2023, research commissioned by Australians for Indigenous Constitutional Recognition (AICR), of which I was a director and spokesperson, assessed just how little-known Indigenous people are, finding that only 15 percent of Australians were aware of the plight of Indigenous peoples.

Months later, just before the October 14 referendum, that poll was conducted again. This was after 70,000 people volunteered for the Yes campaign, at a time when important conversations were being had around kitchen tables and while door knocking and leafleting at train stations and markets around the country was in full swing. This was a time when Australians were getting to know us. The results of that second AICR poll revealed that the campaign raised awareness of our issues to more than 40 percent.

The most important poll, of course, was at the ballot boxes on 14 October. We can take guidance from the correlation between the total Yes vote and the numbers of the second AICR poll, which both sat at around 40 percent.

It seems that support depended on, and continues to depend on, familiarity.

Indigenous Australians are a distinct group. We make up just 3.2 percent of the population, yet we’re 12.5 times more likely to be imprisoned as adults. We’re 26 times more likely to be imprisoned as children, while 61 percent of Indigenous deaths happen before the age of 65, compared with just 17 percent for non-Indigenous Australians. According to the 2023 Closing the Gap campaign report, despite improvements across the health sector, health outcomes remain comparatively worse for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

These statistics tell of a structural problem in the way our country is governed. They make the existence of systemic racism, failed policies and harmful legislation obvious. But these grossly disproportionate rates of illness and incarceration are not who Indigenous people are. They say nothing of our culture, intelligence and DNA, nor do they indicate a lack of love for our children.

Indigenous people are not the sum of their problems.

Many of those who volunteered in the Yes campaign–and many of those that will attend rallies in support of changing the date–were motivated not only by the plight of Indigenous people, but by the joy they experienced when meeting us at events and on country as equals. They were motivated by interacting, listening and making friends.

They learned that First Nations culture is a welcoming and generous culture, a collective culture that cares for our children as a community. For example, our children’s uncles and aunties are as much mothers and fathers as the pair who conceived them. We have deep obligations, not just to our immediate family, but to our broader society, the land and all living things through skin names, totems and moieties.

Within our stories are lessons about life–love, jealousy, responsibility, sustainability–that have been curated and developed throughout countless generations of humanity, and that are as profound and ancient as Socrates’ philosophy and Homer’s Iliad.

Remarkably, the First Nations of this continent were masters at making peace. Hundreds of unique languages could not have evolved on this common continent without expertise at dispute resolution. The Uluru Statement from the Heart is informed by the ancient practice of Makarrata–a Yolngu word for ‘a coming together after a struggle’.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples should not be a source of national guilt. Our nation will be stronger when our Indigenous heritage and culture is recognised, not ignored, as the nation’s proud foundation.

During six years of living and breathing the campaign toward the referendum, a most satisfying experience was seeing the faces of those who did not know us initially, brighten, like when recognising a long-lost friend. I witnessed their dawning discovery that through Makarrata–which also refers to a process of truth-telling and agreement-making that begins with listening–Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s hands were out in friendship, not to take something from them.

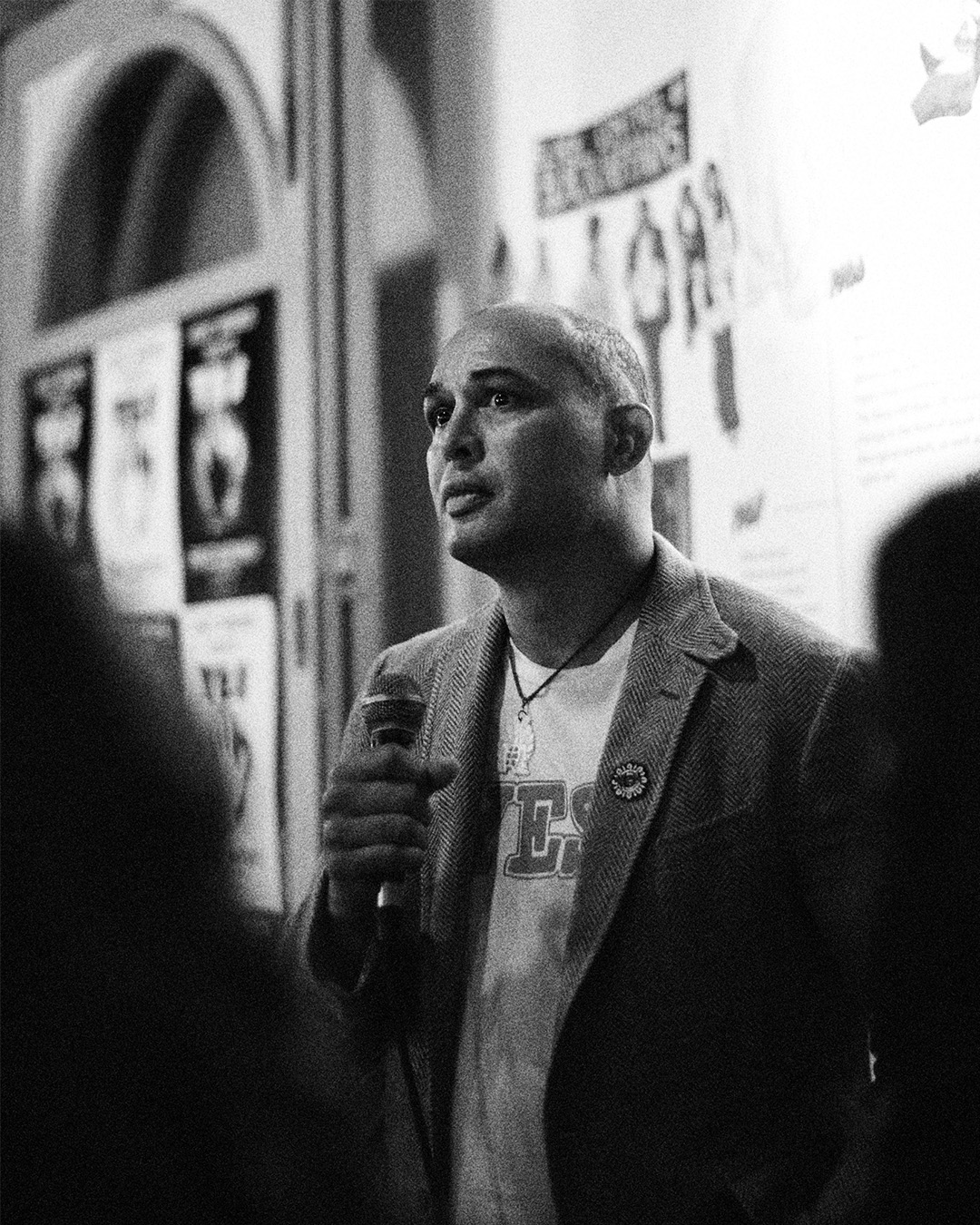

I spoke with hundreds of thousands of Australians at forums, conferences, workplaces and individually. I facilitated gatherings–introductions to Elders and the grandchildren the Yes vote was fighting for. The goodwill and sense of fairness that Australians displayed when they came face to face, hand in hand, with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people–that gave me hope.

It may be many decades before there is another opportunity to recognise the First Peoples in our constitution. But in the months since the referendum, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have dusted themselves off, just as our Elders did when they were told ‘No’ to every piece of progress they eventually gained. We continue to work hard for justice. From the loss, we will get stronger. Our hand remains outstretched.

In all States and Territories on January 26, there will be gatherings of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to mark a day of mourning, the anniversary of the arrival of the First Fleet. It is the day the invasion of Australia began.

January 26 is a day for solidarity, empathy, and an opportunity to get to know us. And all Australians are invited.

My message to Australians who care is to be conscious of your power. I ask that you teach your children, your friends and your family the truth of who Indigenous people are–a proud and unique culture in the world, a source of wisdom, knowledge and connection to our ancient continent.

We all have an ability to perform and engage in this crucial introduction by attending Indigenous events. By being loud and proud in your solidarity, wearing Indigenous labels, supporting Indigenous owned businesses, and by donating to campaigns that will help to close the gap.

The task will be challenging. But like all relationships, we must continue to work on this one–not just so we can end such entrenched disadvantages, but so our children can feel true peace on this shared continent.

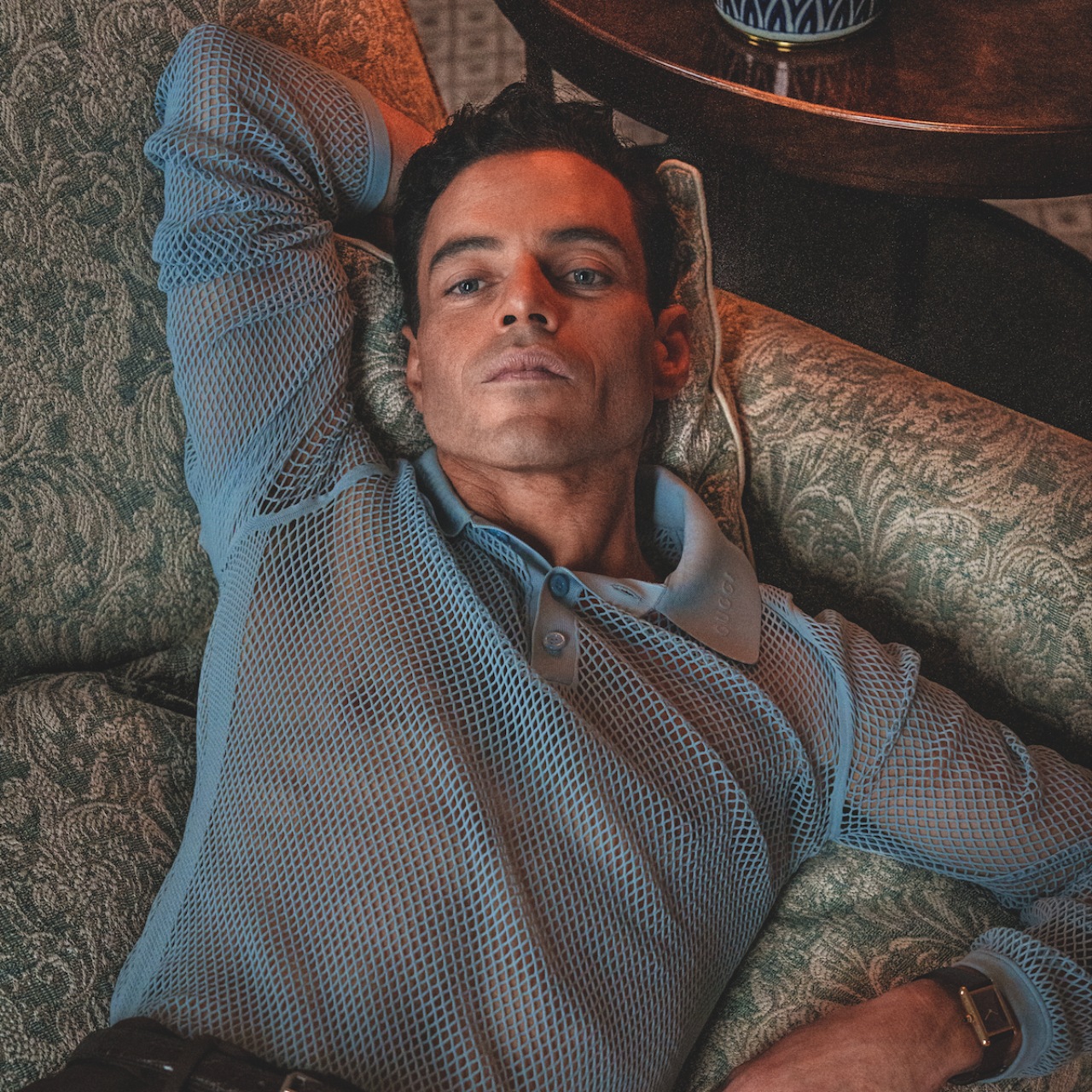

Thomas Mayo is a Kaurareg Aboriginal and Kalkalgal, Erubamle Torres Strait Islander man. He is the Assistant National Secretary of the Maritime Union of Australia (MUA). Thomas is a signatory of the Uluru Statement from the Heart and has been a leading advocate since its inception in May 2017. He is the Chairperson of the Northern Territory Indigenous Labor Network and a director on the Australians for Indigenous Constitutional Recognition board. Thomas is also the author of six books published by Hardie Grant and has many articles and essays published across the major media providers. You can follow him here.

Related:

8 First Nations-owned fashion and streetwear brands to get behind