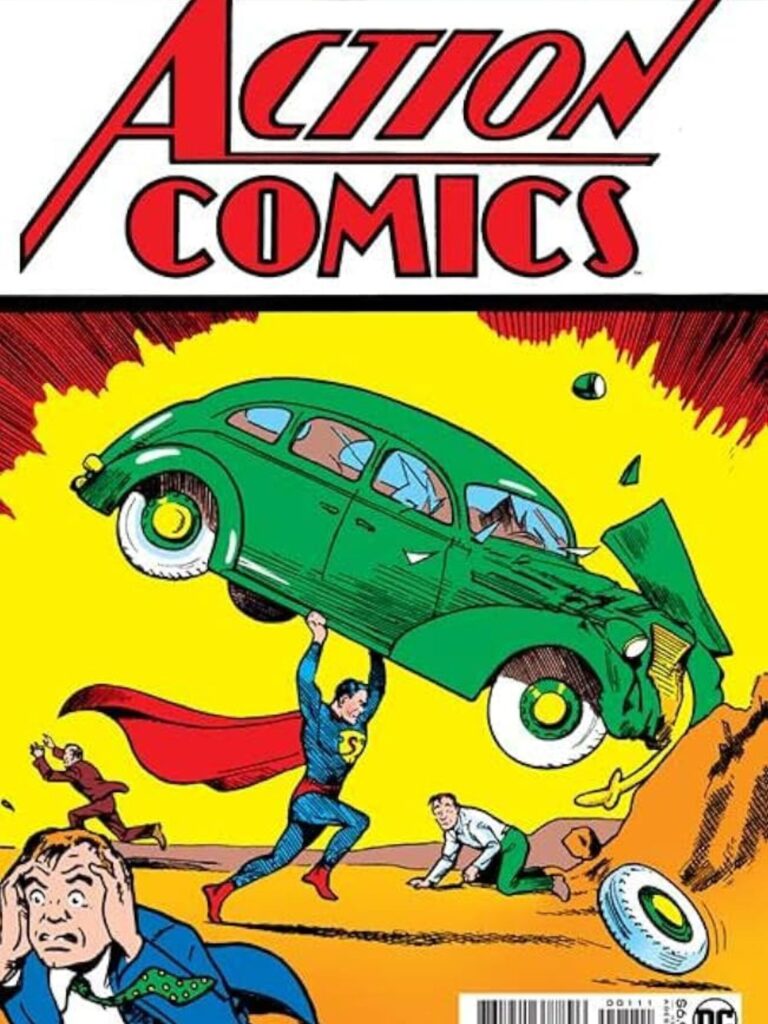

WHEN SUPERMAN FIRST appeared on the cover of Action Comics no. 1 in 1938, he was already a paragon of health and fitness. His chest was broad and his legs were sturdy, but his body was drawn with the lean, simple lines of an Olympic athlete, not a professional bodybuilder.

Early superheroes were strong, certainly – Superman is, in fact, hoisting a car over his head on the cover of the first Action Comics issue – but not swollen. Through the Golden and Silver Ages of comics, Superman, Batman, Spider-Man and their peers were depicted as athletic rather than massive. Take the original on-screen Superman, George Reeves, for example. Reeves was a former boxer and athlete who boasted a naturally solid build, but he didn’t go to great lengths to pack on extra muscle for the role. There was a straightforward reason for this: a superhero’s strength is derived from their powers, not from hypertrophied muscle fibres.

The bodies of superheroes would gradually change. By the ‘70s and ‘80s, as bodybuilding culture crept into the mainstream thanks to figures like Arnold Schwarzenegger, the physiques of superheroes in both comics and film began to shift. They became more exaggerated, with wider shoulders, burnished biceps and torsos shaped like inverted pyramids.

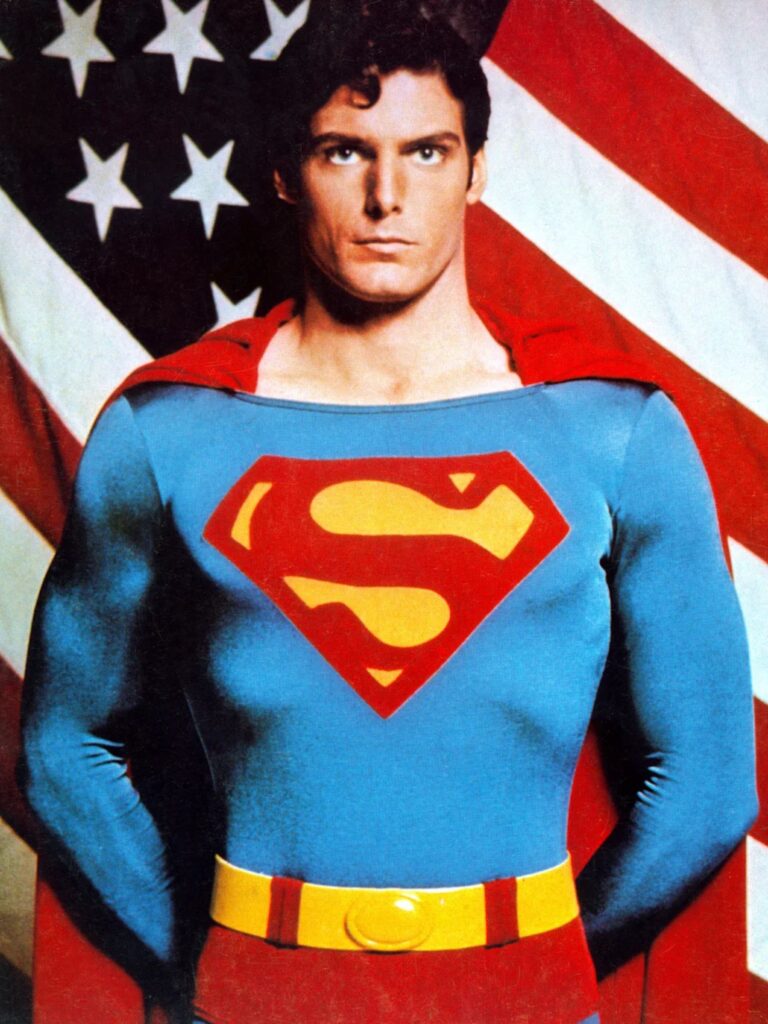

When Christopher Reeve played Superman in 1978, he looked bigger than Reeves, but nowhere near the behemoths that would follow. By the time the Marvel Cinematic Universe exploded in the late 2000s, the physical transformation of its actors became a spectacle unto itself. Behind-the-scenes montages of Chris Hemsworth doing deadlifts or Chris Evans doing a bodyweight circuit became almost as talked-about as the films. Trainers were given the same – if not more – press coverage as directors. What was once make-believe strength became flesh-and-blood muscle.

Today, due to physique inflation, when someone is revealed to be playing a superhero, we don’t ask whether they have the acting skills to sell the part, we begin hypothesising how they’ll train and eat to pack on the requisite size for the role. Muscle has become a kind of visual shorthand, a way to connote a hero’s power to the audience, even when it makes no sense.

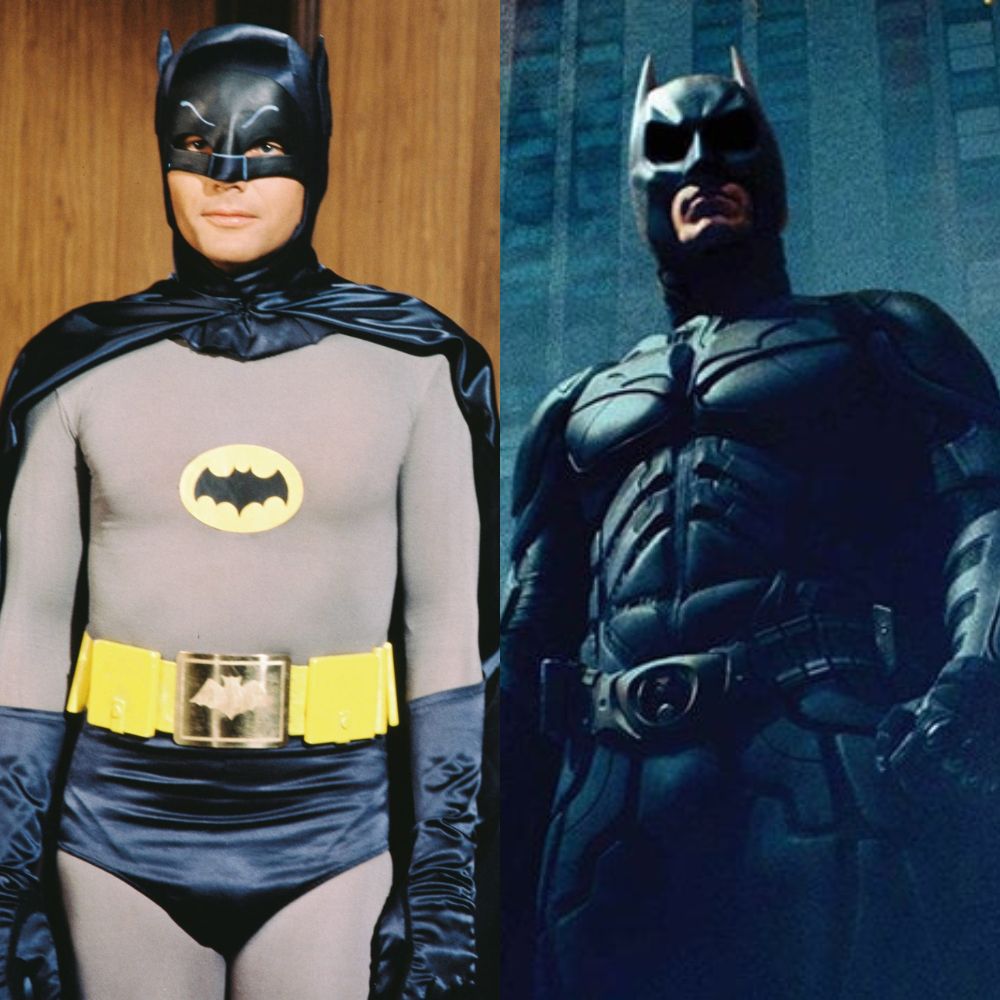

For evidence of physique inflation you need only to look at how Superman has evolved from Reeves to Cavill, or Batman from Adam West to Christian Bale, or, more in a more obvious example, from Hugh Jackman’s first Wolverine to his most recent. The trend has even seeped into side characters. Lex Luthor, who seems far more likely to hire a brolic adversary for Superman than become one himself, received a muscled makeover courtesy of Nicholas Hoult spending plenty of time in the gym ahead of James Gunn’s Superman. We don’t think anyone was demanding that Lex Luthor look a little more shredded.

A reminder: superheroes don’t actually need to be big. Superman draws his strength from the yellow sun, not the hours spent upping his bench press PR. Thor is a god; his hammer, not his deltoids, does the heavy lifting. Even Batman, a logical exception to the rule because of his mortal status, relies on technology as much as brute force.

Consider the Jedi. They are functionally superheroes, with a suite of powers including everything from super strength and speed – though the latter has only been seen once on screen – to telekinesis and mind control. And yet, Yoda isn’t swole. Many Jedi are in great shape – cardio workouts sort of come part and parcel with the job – but none are remotely comparable to Thor or Superman.

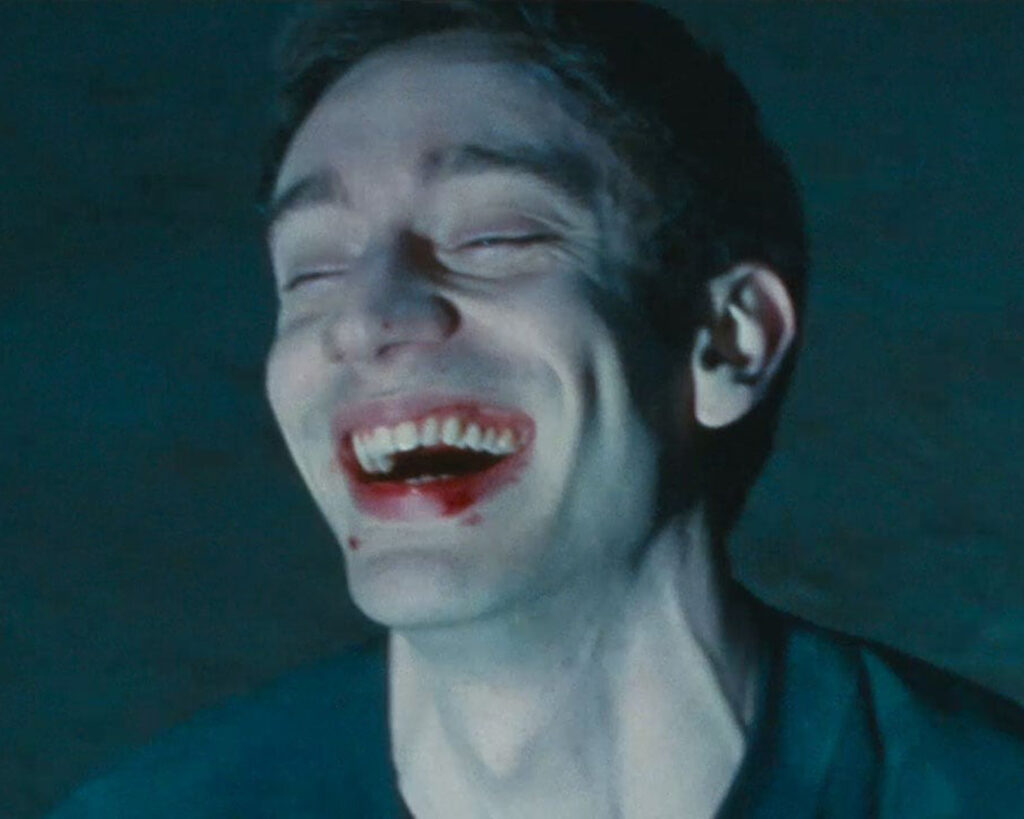

As superhero bodies have gotten bigger, the demands placed on actors to live up to expectations have become more extreme. It’s no wonder some have begun to push back. Robert Pattinson, who played Batman in Matt Reeves’s 2022 film, openly resisted the notion that he had to transform into a powerlifter to play the role. “If you’re working out all the time, you’re part of the problem,” he said in an interview with GQ. “You set a precedent. No one was doing this in the ’70s. Even James Dean – he wasn’t exactly ripped.”

Pattinson would later relent, insisting that he was kidding and had actually been working out. In the end, his Batman was in shape, though not Bale buff.

It seems that the pressure once placed disproportionately on women in Hollywood has, in the superhero era, been redirected toward men. The superhero standard has become a benchmark of unattainable masculinity, one that requires extreme diets, supplements and sometimes more dubious enhancements.

What will it take to reverse this trend? Perhaps one brave actor will lift the lid on PED use, causing a scandal similar to the discovery of steroid use in baseball that ultimately brought about its end. But then again, given that many already assume actors are on PEDs, perhaps no one would care. A Pattinson-esque actor could also become an advocate for slightly smaller physiques. They might even start a trend.

Maybe, just as the demand for superhero films shrinks, superhero physiques will shrink along with them. Actors may find it’s not worth getting big if the film isn’t a surefire blockbuster.

Or alternatively, we might collectively realise that the most compelling superheroes have never been compelling because of their bodies. They endure because of the ideals they represent. Audiences connect with Spider-Man not because of his lats, but because he struggles with responsibility. We love Iron Man not because of his abs, but because his arrogance is matched by his willingness to change. Even the Hulk, the most obvious symbol of muscle-as-power, is really about controlling rage. The stories work because of the characters, not the circumference of their biceps.

Maybe the next generation of heroes won’t need to be super-swole. Maybe they’ll remind us that true strength has never been about size, but about what you do with it.