Will Drake's new book get more men reading poetry?

In this week's edition of 'Winging It', Jonathan Seidler looks at the peculiar trend of high profile men branching into poetry.

Jonathan Seidler is an Australian author, father and nu-metal apologist. You may have read his memoir, caught his compelling live performance at this year’s Sydney Writers’ Festival, or noticed his distinct eyebrows on the street. He has some interesting things to say about music, fatherhood, Aussie culture, mental health and the social gymnastics of group chats. This is his column for Esquire.

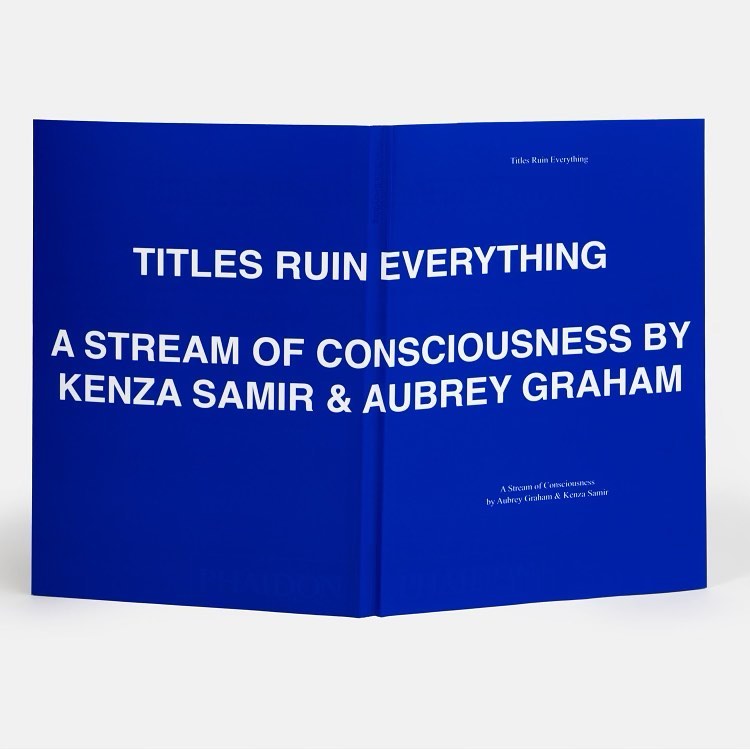

Canadian music monolith Drake recently announced the launch of his newest project with a full-page wraparound in The New York Times. He’s a low-key guy. It’s called ‘Titles Ruin Everything’, a book of poetry to be released through highbrow art book publisher Phaidon, which is also well known for publishing the design bible Wallpaper*.

Naturally there’s an album to accompany it, but that’s besides the point, as is Drake’s preeminent role as the guy who performs rhyming couplets over sick beats to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars.

In an attention economy where songs regularly need to outperform their competitors in the first 15 seconds so as to charm the TikTok algorithm, it’s curious that the man born Aubrey Graham, a rapper so perennially ’online’ that he regularly spoofs himself with the express purpose of launching a thousand memes, should decide to invest significant time, effort and funds into such a deliberately slow medium as poetry.

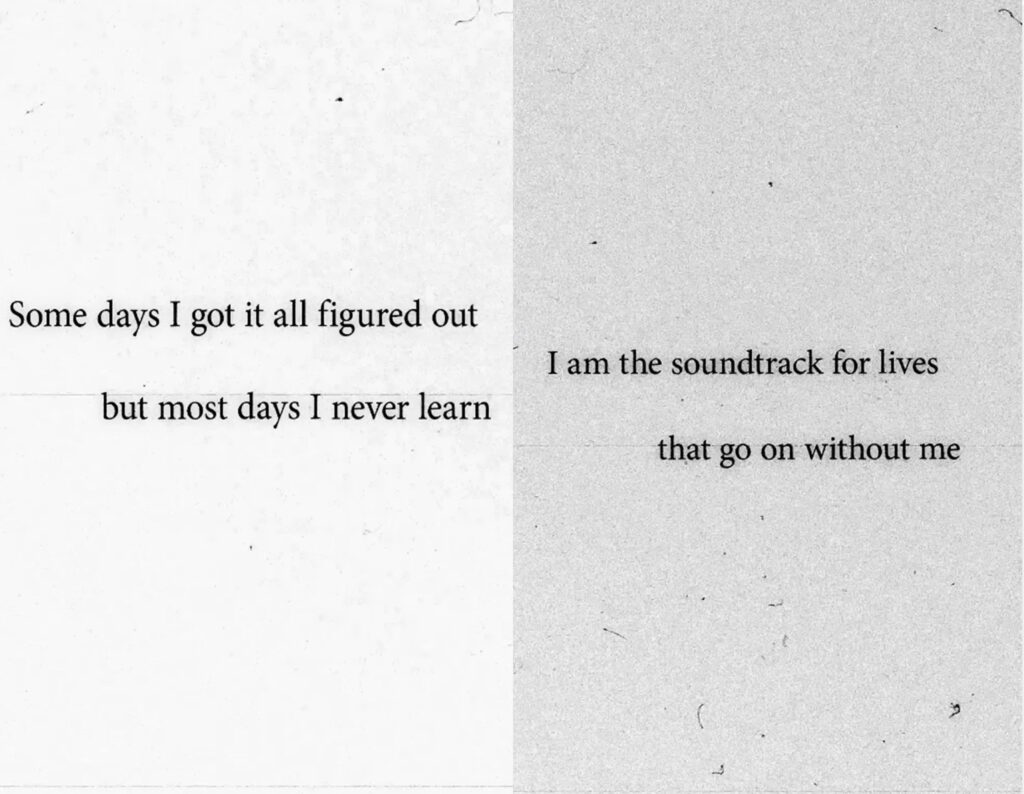

We still have little idea of TRE’s contents. Early press indicates the poems are little more than a collection of killer one-liners, something Drake has already made a cornerstone of his career. And really, in the aforementioned attention economy, who are we to decry a one line poem?

‘I am the soundtrack for lives that go on without me,’ reads one such early work released (on Instagram, of course) by Drake’s new publisher. Could it be our generation’s ‘For sale: baby shoes never worn’?

Phaidon says Drake “has been writing poetry as a means of personal expression for quite some time.” This makes more sense. Drake has famously made wearing his heart on his sleeve a personal brand. Discussing one’s emotions is not a new phenomenon for a man who once topped the Billboard charts for ten weeks with a song entitled ‘In My Feelings.’

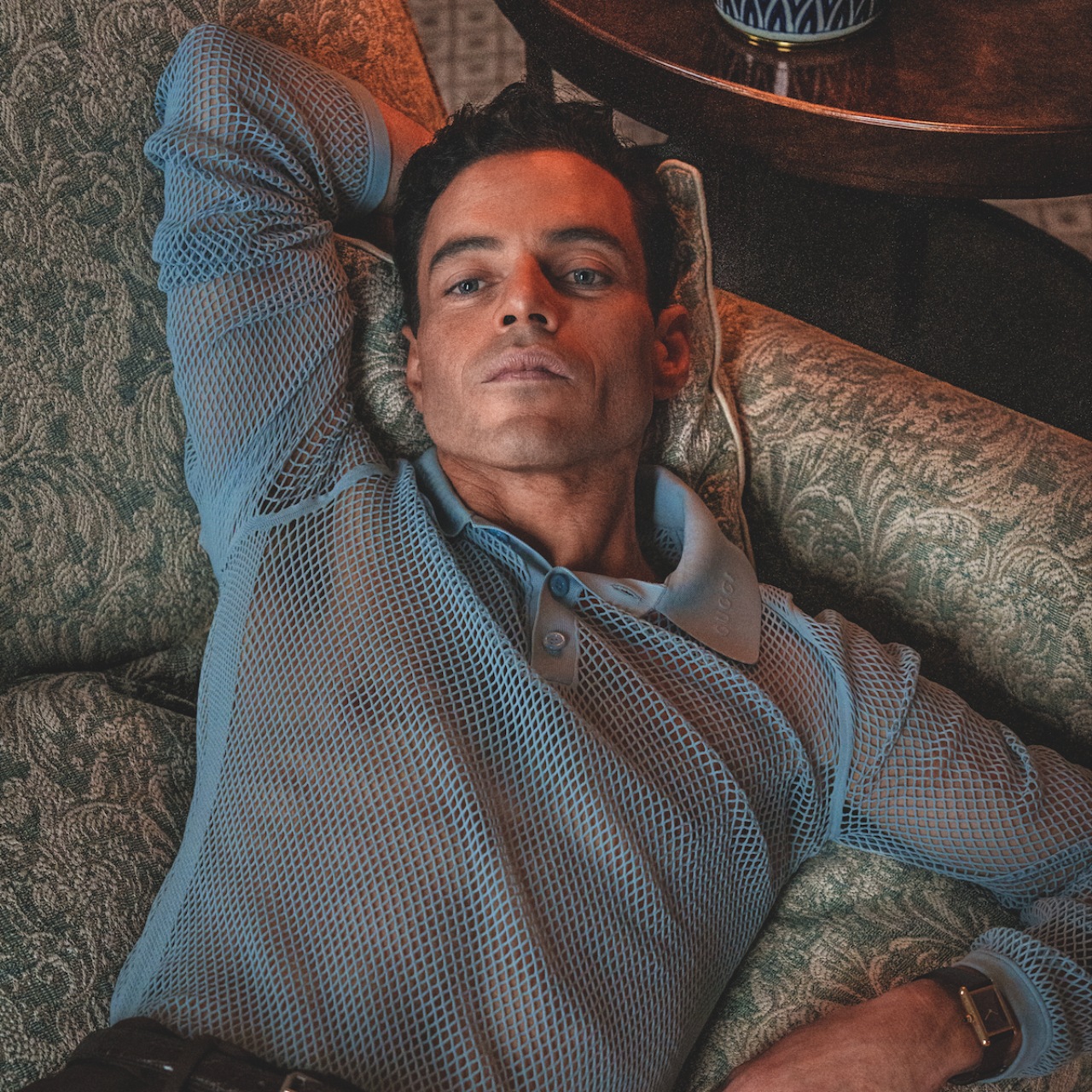

But absent the club-ready beats of his right hand man Noah ‘40’ Shebib, poetry lays Drake bare. He cannot rely on expensive video trickery or a rare pair of Jordans to shimmy his way out of bad prose. At the apex of his career, with an armada of imitators and a frankly ludicrous bank balance, it seems like a pointless risk.

Unless Drake is trying to tell us something.

One of the most successful crossover poets in recent years is Ocean Vuong. His recent collection, which often feels almost lyrical in its beauty, is so popular that Vuong’s publisher recently announced they’d be pressing new recordings of them to vinyl. At the same time as songwriters are becoming poets, poets are becoming songwriters.

But while more high profile men are releasing poetry, their audience doesn’t reflect this. There’s a truism in the Australian publishing world that even men’s interest titles are ultimately targeted at women, who do the lion’s share of the purchasing. In the case of poetry, however, it rarely sells well. (I had two Australian book publishers confirm this, though for obvious reasons, they were hesitant to go on the record). And even when someone as successful as Vuong (or closer to home, Evelyn Araluen) breaks the mould and it does, it’s typically not being bought for — or by — blokes.

For most men, poetry is a thing we were made to read at school, forced to remember every time we sung the national anthem or tried and figure out if it’s indeed beer before grass that puts you on your arse. Having something drilled into you this early — in my case, it was trigonometry — is a surefire way to guarantee you’ll never touch it again.

This is a shame, because poetry teaches us how to express a lot with a little. It is valuable for its economy, its nakedness, the way in which it can create worlds or stop our hearts in only a few stanzas. There’s nothing on Earth like it.

“I think musicians are gravitating towards poetry as a site to be confessional and emotional, without the extra layers of production,” West Australian poet Madison Godfrey told me recently. “Reading a poem can feel like being told a story in someone’s bedroom, as opposed to overhearing a story in the crowded bar of a pop song.”

With Vuong and now Drake, we find ourselves somewhere closer to that bedroom, a rarified space in the middle of a music and literary Venn Diagram that’s currently the domain of multi-disciplinary wordsmiths like Omar Musa and Kae Tempest. Hell, if there’s even a handful of guys that want to get into the exhilarating work of Jazz Money or Tony Birch after devouring the inner machinations of Drake’s id, we should chalk that up to a win.

The world’s most famous Toronto native probably isn’t on a noble mission to make more men read T.S Eliot. But by releasing poetry deliberately in this fashion — “I made an album to go with the book,” reads his website — he sends a message about the value he ascribes to words, and the care he takes in arranging them. There’s also a lesson in here about the value of paying attention, from a man who made most of his fortune trying to distract us.

And yes, Kendrick already won a Pulitzer. But as Drake well knows, he didn’t win it for poetry. That sucker is still wide open.

Jonathan Seidler is an Esquire columnist and the author of It’s A Shame About Ray (Allen & Unwin).

Like all proper columns, this one will be back next week. You can see Jonno’s first column for Esquire here.