How the new creative directors will change the way we shop for luxury

All eyes will be on the runway when, this June and September, a new guard of designers unveil their debut collections for some of the world’s biggest fashion houses in an attempt to reinvigorate luxury spending. Yet next to the clothes themselves, one of the biggest statements of intent can be found in the way creative directors gut – and reimagine – the architecture of their stores

Correction: This story was written before it was announced on June 2, 2025, that Jonathan Anderson will also be the creative director of Dior womenswear and haute couture, making him the French house’s sole designer.

THE EXTENDED PERFORMANCE of creative director musical chairs at top luxury fashion houses has ensured that, among other things, we all recognise a brand reset when we see one. Phoebe Philo acolytes will continue to curse the day Hedi Slimane arrived at Céline; he dropped the accent aigu from the brand’s name immediately, prying it off the store fronts he rendered in austere marble, black and metal. Daniel Lee ushering in a return to British heritage at Burberry also comes to mind, as does Riccardo Tisci before him, with his gothic Italianate streetwear as minimal as the Sans Serif font of his reimagined logo.

Yet not all inception points are quite so abrupt. An afternoon spent at the new Loewe store in Sydney offers the coda to Jonathan Anderson’s 12-year tenure at the brand. Taking pride of place in the front window display is a five-foot high totemic sculpture by the Mexican ceramicist Andrés Anza; rug tapestries from British textile artist John Allen’s Woven England series lay underfoot. It feels like walking inside a collector’s apartment (a retail concept the Spanish brand terms ‘Casa Loewe’); every piece of furniture and artwork in the store is linked, in some way, to Anderson’s own taste for collecting ceramics, paintings and other monuments of craft.

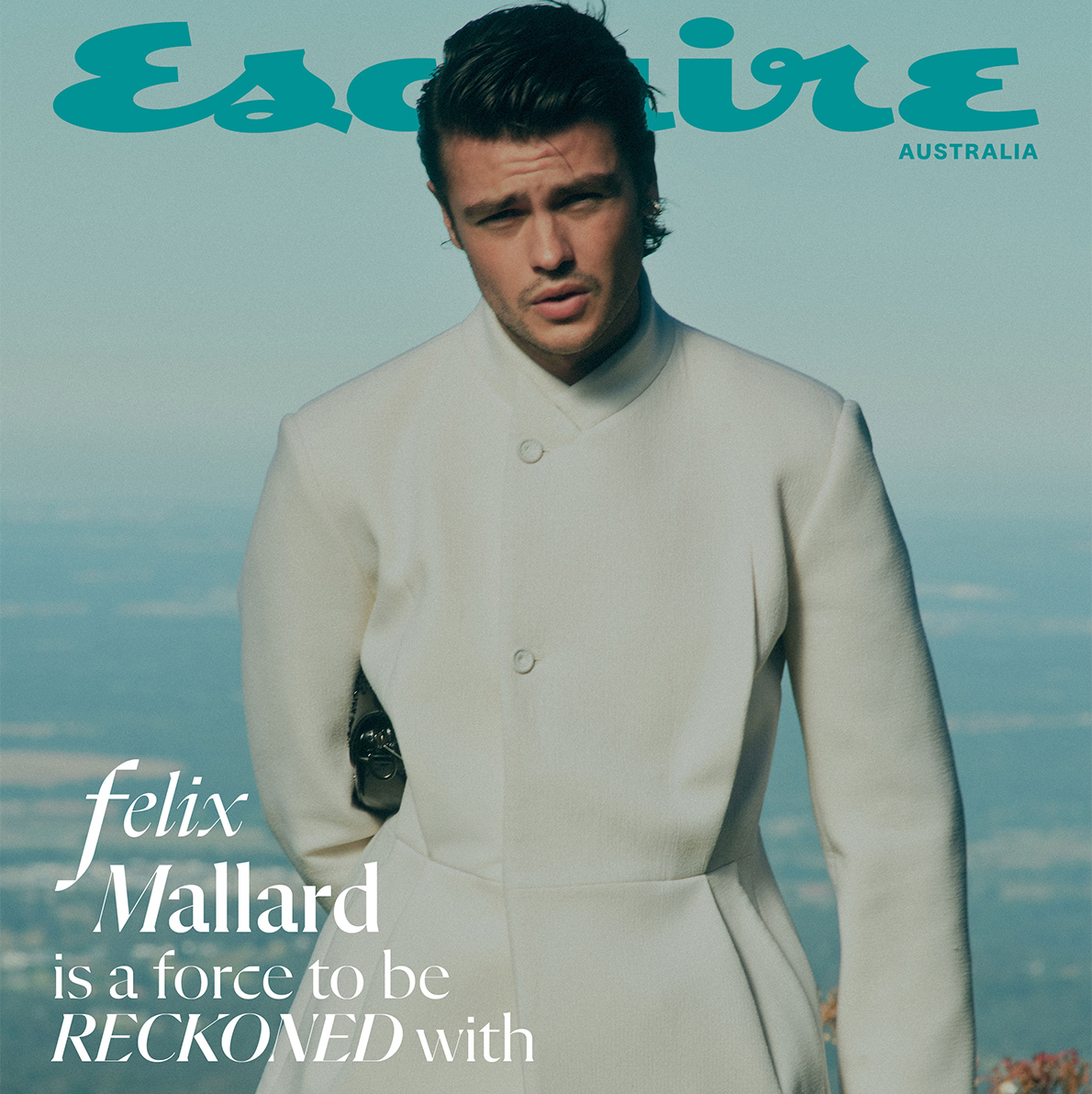

Anderson’s patronage of the arts, and coterie of artists and collaborators he surrounds himself with, is partly what defined his cultural reinvigoration of the 179-year-old Spanish leather goods brand – in 2016, the Northern Irish designer inaugurated the Loewe Foundation Craft Prize, for which Anza won the €50,000 first-place award last year. That this new Sydney store feels like a shrine to the aesthetic he established is interesting – it opened its doors just weeks after it was announced that Anderson would be departing Loewe to join Dior as its new artistic director of menswear, succeeding Kim Jones, who’s held the role since 2018. An indication, perhaps, that the brand’s new caretakers – Jack McCollough and Lazaro Hernandez of cult American brand Proenza Schouler – have been instructed not to fix what isn’t broken. Loewe was named the world’s hottest brand in the first quarter of 2025, according to the Lyst Index, after all.

If you have been paying attention to other high-profile appointments (and dismissals) in the luxury fashion sphere, you’ll be aware that in addition to the new collections – Anderson will debut his first Dior collection during the spring/summer 2026 menswear shows in Paris in June – in most cases, with cleaning house comes new store fit-outs.

“You can think of retail architecture as a kind of manifesto,” says Kelvin Ho, founding director of Australian architecture firm Akin Atelier, who has created flagship spaces for Australian retailers from Bassike to Incu. “When a new creative director steps in, a store redesign becomes a way to align the brand’s physical presence with its new direction. It’s about creating a visual coherence between the clothes and the context in which they’re experienced.”

In direct opposition to the unveiling of the new Loewe store, one of the most stark brand resets we’ve seen in recent years occurred in late 2022 at Gucci. Alessandro Michele’s fruitful seven-year reign at the 104-year-old Italian fashion house had come to an end; the ‘magpie maximalism’ he was known for – his store interiors and window dressings were resplendent in velvet and sequins, like the dressing room of a Golden Age Hollywood actress – were stripped bare in preparation for what was to follow.

In early 2023, Gucci’s parent company, Kering, announced that Sabato De Sarno, the then-fashion director at Valentino, would be taking over from Michele. The Neapolitan designer was tasked with staging a 180 of the brand’s aesthetic (revenue growth had been stagnating under Michele, and the maximalism that defined luxury in the 2010s had fallen out of favour in the COVID era, replaced by a style of minimalism the internet has since appropriated as ‘quiet luxury’). Ahead of De Sarno’s runway debut, the store’s ornate carpets were rolled up and swapped out for grey ones; the façade boarded up for renovations and remade in cold marble, a deep wine hue named ‘Rosso Ancora’ covering every surface.

Michele and Anderson form part of a generation of superstar designers from the last decade whose strength in personality and image-making defined a new and enticing definition of luxury. They remade the brands in their own image, rewrote the rules of exclusivity and ensured their vision flowed from the runway to marketing campaigns and into the physical brick-and-mortar manifestations of the universes they created.

“For decades, luxury brands maintained their extraordinary margins through a monopoly on fiction,” says Eugene Healey, an Australian brand strategist and content creator, referring to the brand narrative that is spun, storybook style, by a creative director. Meanwhile, he points out that “luxury brands have strategically dismantled physical scarcity to achieve scale”, while the image-dominated world we live in has caused a cultural oversupply of luxury”.

Speaking to the current onslaught of creative turnover, Healey suggests that conglomerates are hoping to return this worldbuilding authority to the hands of big-name designers, instead of “the brand showing up through somebody else’s eyes and context [like] creators, curators, gatekeepers, partners”. For a new creative director, what the store space presents is “it’s the one area the brand shows up unmediated”, he says. “It’s the place where the creative director can introduce the consumer to a pure version of the brand’s desired fiction, and communicate how the fiction-slash-world is distinct from what comes before.”

A similar process of wiping the slate clean to establish whole new worlds is destined to happen again within the next year – Haider Ackermann’s first collection for Tom Ford will hit stores in September, as will Sarah Burton’s for Givenchy, while Demna’s highly anticipated debut for Gucci will also take place in the early Northern autumn. Only this time, with the speed and frequency with which these reshuffles are taking place, “the message see-saws, and becomes so convoluted”, Dana Thomas, author of Deluxe: How Luxury Lost Its Lustre, tells Esquire Australia. “Stores are redecorated, and redecorated again. That’s how you lose customers, unless you commit to the new message fully.”

As for a way out of the current luxury spending slump, brands seem to think the solution lies in appointing a creative director with a cult following.

“When it’s time for a reset, like at Gucci when Tom Ford took over in the mid-’90s, and Gucci again now, with Demna, the creative director has to conceive a new message, really remake everything the brand is communicating, from the clothes to store design,” explains Thomas. She nods to Demna’s decade-long tenure at Balenciaga, where his redefinition of new luxury was born in putting domestic debris – IKEA totes, Crocs, shopping bags, towels – on the runway, his stores equally incongruous in sober concrete. It proved successful: revenues grew to US$2 billion at the brand’s peak in 2022, compared to a hovering estimate of US$350 million when he arrived. While, like Michele, Demna’s radical repositioning of luxury eventually lost its shine among consumers, no doubt his track record of conjuring magic is part of what Kering CEO François-Henri Pinault hopes to transfer to Gucci.

While the runway is where we get the first glimpse of the clothes, and Instagram is where we first encounter a marketing moment, stores remain the touchpoint at which most consumers encounter luxury items; the contexts in which they come to life. “It’s where the brand either seduces us to part with our money, or not – in those first few steps inside,” says Thomas. “We either understand the brand message and point of view – and want to be a part of it – or not.”

This story appears in the Winter 2025 issue of Esquire Australia with the title “Luxury Renovations”, on sale now. Find out where to buy the issue here.

Related:

What happens when fashion, entertainment and culture collide?

Where to get authentic Spanish fare in Madrid, according to designer Edward Cuming