‘All Eyes On Rafah’ and the complexities of social media activism

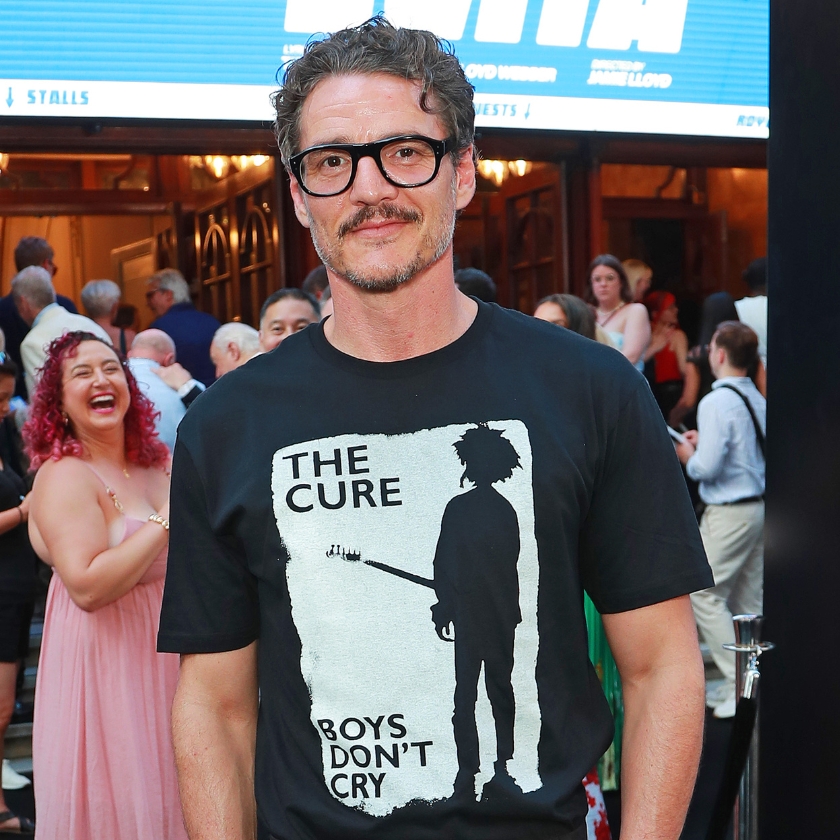

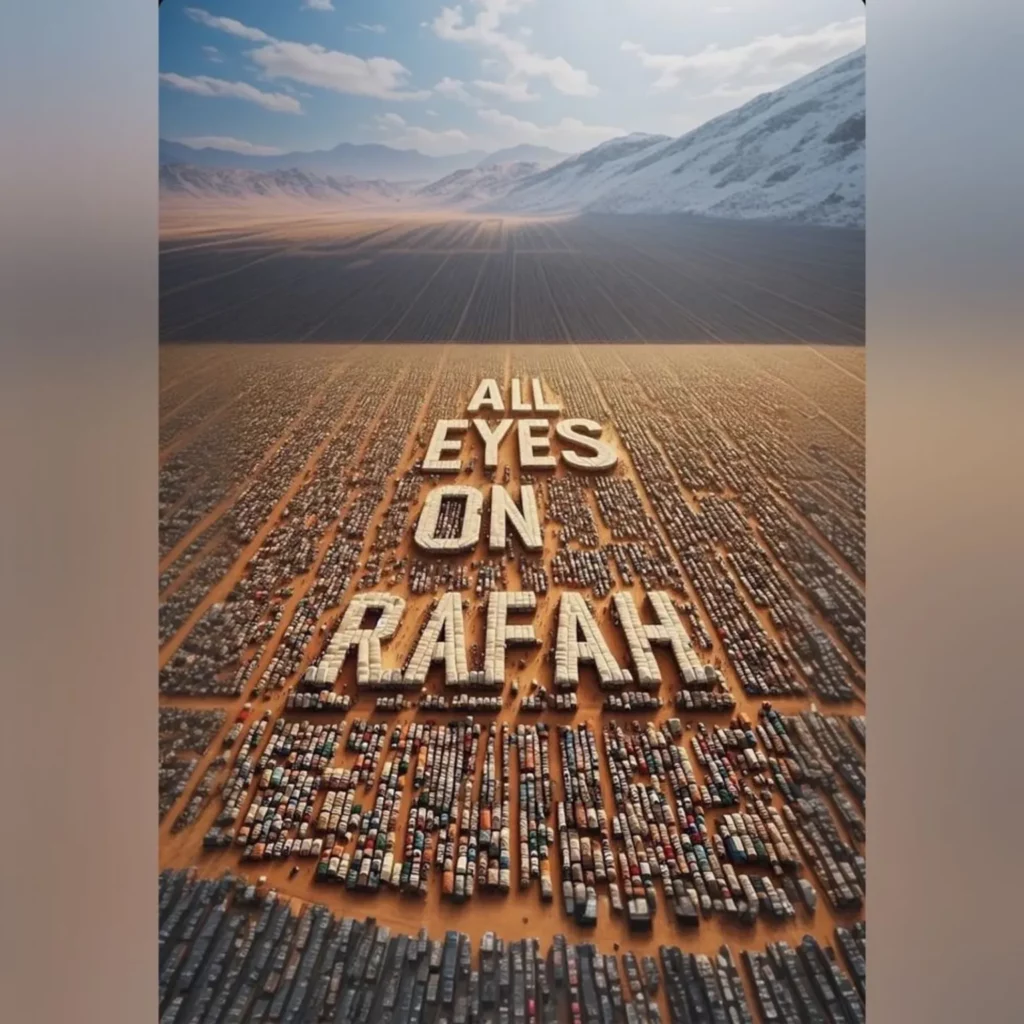

This week the AI-generated image tile, ‘All Eyes On Rafah’, went viral on social media channels, shared by many who’ve never previously been engaged with the conflict in the Middle East. Is this a problem?

THE IMAGE BEGAN hitting my Instagram feed on Tuesday afternoon. ‘All Eyes On Rafah’ in bold, 3D capital letters, looking at first glance like a movie title, rather than what it was – an AI-generated image representing a tragedy.

Soon I was seeing it all over my account as friends and acquaintances shared it on their feeds and stories. The image has since been shared over 47 million times, including by celebrities like Dua Lipa, Lewis Hamilton and Gigi and Bella Hadid.

The image’s virality has been spurred by the fact that it’s an Insta stories template, making it easily sharable. Reports have linked the phrasing of the words back to comments made by the World Health Organisation’s representative for the West Bank and Gaza, Richard Peeperkorn, during a press conference back in February. He said “all eyes” were on feared hostilities in Rafah.

It’s gone viral now after recent attacks on people sheltering in tents in Rafah sparked international outrage. The image’s lack of graphic content – such as the bodies of victims – has also contributed to its pervasiveness, sheltering it from the attention of Instagram’s moderators.

The question is, does simply posting the image serve a purpose? Objectively, there is a case to be made that it does.

“This image serves as a token of support for Palestinians at a time when many users might not be able to witness the events on the ground – whether because of connectivity issues, or platforms’ policies on moderating violent imagery,” Olga Biochak, director of the University of Sydney’s Computational Social Science Lab, told the ABC.

Therein, however, is where the complexities of digital activism begin, for it is the often-‘token’ nature of social media support that invites a cynical reaction to tiles such as ‘All Eyes on Rafah’ (AEOR) and before it, the BLM black square that many people, myself included, added to their feeds back in 2020.

Many of us will instinctively dismiss the posting of a tile like AEOR as performative activism or virtue signalling, particularly when we believe the poster is not someone deeply committed to the cause in question. The Betoota Advocate, in their imperious way, summed it up thus: “Albo under pressure to condemn Netanyahu after Instagram models educate their tradie followers about what’s happening in Gaza”.

I must admit my first reaction to seeing the posts crop up in my stories feed was a cynical one; a metaphorical eye roll, if you like. Later, however, I found myself researching the background and purpose behind the image, in the process learning more about the conflict in Gaza than I’d previously been inclined to seek out. The image had served a purpose.

But I didn’t share it on my own account for reasons that I’m still grappling with. Social media, by nature, is inherently performative, something I often find problematic, yet unable to resist. My feed is mostly curated around work, pictures of my daughter and travel. Posting an AEOR tile would have been a drastic departure from my normal programming. But more importantly, I didn’t feel that it would be authentic. I have not attended any of the rallies in protest of the conflict in Gaza. My support would have been wholly token in nature.

It would not, however, have been mindless, for I am certain I would have agonised about how it would be received by friends and acquaintances. I would have worried that they would roll their eyes, as I had previously done and dismissed me as a passive digital activist. Similarly, if I were to post the tile now, a few days removed from its algorithm-rupturing peak, I would then worry that I’d be seen as either late to the party or a bandwagon-trailing hack.

I had similar overthought misgivings about the black square of the BLM movement, but on that occasion I mentally justified my engagement as being a person of colour and wanting to show solidarity – not that allies who aren’t of colour can’t also show their support. While my decision to post was predicated on a perceived sense of solidarity, it was one made in the absence of any tangible action – I did not attend any rallies or donate any money to that cause.

I remember pushing the post button and mentally cowering as I worried about how the black square would be received. So, what happened? You’ll probably be surprised to hear this, but essentially nothing. My post collected a few likes and now stands as a stark outpost on my grid, a black square that clashes violently with the filtered images of my daughter flying a kite or a view of a sunset. I felt a little grubby afterward, like a digital fraudster.

To make matters worse, I later learned that the widespread sharing of black squares was possibly drowning out vital information and amplification for the BLM movement, such as information about protests and bail funds.

Token digital activism raises broader questions about how much our social media presence should align with our IRL lives. Do only those who’ve attended rallies or donated money have the right to post on these issues? Should we condemn those who post without putting boots on the ground? To add another layer – are those who attend rallies and wear badges and T-shirts, also performing to some extent? You could argue that one of the reasons for Gen-Z’s embrace of social activism over Gen-X’s rejection of political engagement, is because they can post about it – if you attend a rally without posting about it, did you even go?

Where you land on these questions is, of course, for each of us to decide. What I would say – after a lot of overthinking – is that if we let perceptions of how others view us prevent us from following an impulse to post something that, at the very least, might raise awareness about an issue of humanitarian importance, then we are perhaps letting our insecurities hold us back.

I would also add that Instagram has long been maligned as depicting idealised versions of our lives – pink sunsets, dappled gardens, glistening rib-eyes. It’s not, in most cases – including mine – a genuine reflection of our daily existence.

A determined pursuit of authenticity and alignment between our digital and real lives is probably too ambitious for most of us to achieve and would likely require a commitment to asceticism and willingness to sacrifice that many of us would find impossible. In my case, it would require me to post my daughter’s meltdown in Woolies, my daggy double-chinned happy snap from the Goldy, or, if I was truly committing to the ‘bit’, a picture of my TV screen and the couch.

In that sense, posting a mildly political but largely benign Insta tile is probably not worth losing sleep over. It may even be ‘on brand’ for me after all, which admittedly, is a crass and possibly repugnant conclusion to reach as a tragedy continues to unfold.

Related:

Donald Trump is officially a convicted felon. Can he still run for President?