Costner, Coppola and the merits and risks of directors bankrolling their own films

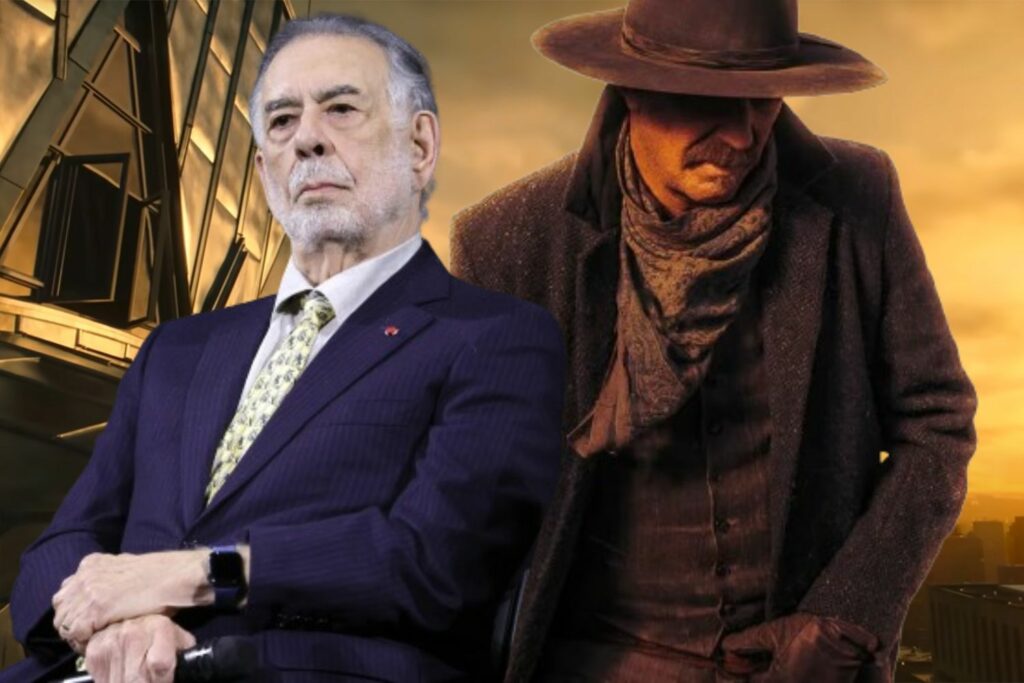

As the curtain closes on Cannes, much of the discourse has surrounded two films: Kevin Costner's dizzyingly ambitious 'Horizon: An American Saga' and Francis Ford Coppola's long-term passion-project 'Megalopolis'. Both were bankrolled by their directors after struggling to secure funding from major studios. Will betting everything pay off?

AN EXCEEDINGLY QUESTIONABLE amount of stock is put into standing ovations at major film festivals. Perhaps it’s because we find the thought of getting a stopwatch ready the moment the credits start to roll comical, but attributing a film’s value to time spent standing and clapping seems like an exercise in farce. Nevertheless, here’s the obligatory standing o’ stat: Horizon: An American Saga and Megalopolis both garnered seven minutes of ovation at Cannes. But that’s not all they have in common.

In case you blazed through it, the introduction to this article already established that both Horizon and Megalopolis were largely funded by their directors, but what they also share is a polarising critical reception – which should, if nothing else, serve as proof that standing ovations aren’t always an indication of good cinema.

IndieWire called Costner’s old-school Western epic set against the backdrop of the American civil war the “dullest cinematic vanity project of the century”, while the BBC described the film as “a numbingly long, incoherent disaster”. On the other hand, Vulture is at least reservedly positive, likening Horizon to “Dune: Part One” but “for dads”.

It was similar fare for Coppola’s tale of an idealistic architect rebuilding a decaying cityscape after a devastating accident, Megalopolis. The Ringer called it a “big, beautiful mess”, The Guardian says it’s “megabloated and megaboring”, but The New Yorker took a different view, labelling it as “madly captivating”.

It’s difficult to discern what the consensus is for Horizon and Megalopolis when the early reviews were, to take an optimistic view of their reception, hot and cold. But mixed reviews are not what a director going all-in on a project wants to hear. If either Costner or Coppola wants to salvage any morsel of commercial success – and avoid outright bankrupting themselves – they need every critic to be waxing lyrical and every moviegoer to be telling their friends and family about the brilliant film they’ve just seen, because we’ve hardly ever seen a director swing for the fences like Costner and Coppola are right now.

Costner, the director, writer and star of Horizon, put up $38 million USD of his own cash for what is only the first of what he says will be four chapters in the ‘American Saga’, after the film wasn’t picked up by any major studios. His fund-raising efforts included taking out a mortgage on his Santa Barbara estate. “I’ll risk those homes to make my movies,” he said in Cannes. Costner also says he quite literally went door to door in Cannes like a salesman to secure further funding for future chapters from residents of the French city.

“I don’t know why it’s so hard to get people to believe in the movie I wanted to make,” he admitted during a press conference last week in Cannes. “I don’t think anybody else’s movie is better than mine. I made it for people… My problem is that I don’t fall out of love with something that’s good.”

Coppola, meanwhile, has placed even more of his own chips in the pot for Megalopolis. Coppola has been trying to get Megalopolis made for a long time, having first been struck with the premise in the ‘70s. But his vision for the film was so ambitious – and so expensive – that studios wouldn’t touch it. He wasn’t going to simply give up though. Through the sale of his vast winemaking empire, the legendary auteur was able to front $120 million USD to fund the film.

Both Costner and Coppola are betting it all on their latest projects, but right now, neither has much going for them. So, will their gambles pay off? The clearest answer may lie in the past.

What directors have financed their own films?

Earlier, we said that we’d hardly ever seen a director put as much money into their own work as Costner and Coppola. ‘Hardly’ was the operative word there. For while it is rare, a small selection of films have been made – and have even found success – after their directors put their livelihoods on the line for the sake of the film. One such director was Francis Ford Coppola himself, who risked it all for the grossly over-budget Apocalypse Now.

It’s possible that no film has had a more tumultuous production period than Apocalypse Now. With filming beginning on location in the Philippines in early 1976, it was only a few days before Coppola had dismissed Harvey Keitel, who was originally cast in the leading role. A few months later, typhoon Olga destroyed most of the film’s sets, forcing production to be temporarily halted and cast members to return home as the crew attempted to salvage a film that was already looking like it would never see the light of day.

At the time, Apocalypse Now was already $2 million over budget. Determined to get it made, Coppola took out a larger loan from United Artists (the studio funding the film), with the stipulation that if the film didn’t gross for more than $40 million, he would cover the difference.

By mid-1977, when Apocalypse Now was finally approaching post-production, the film’s budget had doubled, and United Artists had so much at stake they took out a $15 million life insurance policy on Coppola. While the director himself was using his house, car and profits from The Godfather as collateral in case creditors attempted to renege on any deals.

Apocalypse now finally premiered in 1979, becoming widely recognised as not only one of the greatest war films, but one of the greatest films of all time. It will be Coppola’s hope that Megalopolis has a similar fate.

Coppola wasn’t the only director to go rogue in the late ‘70s. His long-time friend George Lucas made an even larger investment in Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back. Lucas was hardly strapped for cash following the success of the original Star Wars film and had offers from countless studios for the rights to its sequel, but that wasn’t what Lucas wanted. Instead, The Empire Strikes Back was funded entirely out of Lucas’ pocket, as the director wanted to ensure complete and total creative control over his brainchild. With The Empire Strikes Back becoming arguably the most celebrated science fiction film of all time, it’s hard to argue with the results of Lucas’ methods.

Are there any benefits to a director financing their own film?

Lucas’ motives bring us to one of the key benefits of a director-funded film: creative control. While helming a regular, studio-funded film leaves a director beholden to the whims of studio executives and shareholders, by being the majority stakeholder in a film, a director can make just about any creative decision they please without as much as a second word from those around them. Don’t think the film should have a naively optimistic ending? Change the script! Tired of that petulant actor who can’t get his lines right? Sack him and replace him with a hand-picked candidate!

This is the covetable position that Costner and Coppola are in right now, although it does come with some downsides. When the two provided examples (Apocalypse Now and The Empire Strikes Back) are pure gold, you might wonder why the director-funded approach isn’t advocated for more often, but giving one person full creative control over a film won’t always result in a magnum opus. Just as often, the end product will be a vanity project that’s only palatable to a select group of people who share the director’s distinctive tastes. If the early reviews for Horizon and Megalopolis are anything to go by, it would seem Costner and Coppola’s projects are leaning towards the latter.

Will Costner and Coppola’s gambles pay off?

We’re down to the all-important question. Will Costner and Coppola going rogue produce a pair of masterworks, or will their films crash and burn, taking their directors with them? Given the current slate of evidence and the early reception of the films, it seems likely that they’ll fail, at least commercially.

Sure, Apocalypse Now and The Empire Strikes Back were massive commercial successes, but when he made Apocalypse Now, Francis Ford Coppola was the director of the moment, having just masterminded the first and second Godfather films, but not yet making the mistake of conceiving a third. Likewise, the first Star Wars film was the highest grossing film of all time, its sequel was always going to make money.

It would be a surprise if either Horizon or Megalopolis became a commercial success. Neither is the type of film that makes cinemagoers flock to the theatre to see. And in the current landscape, a three-hour film that only serves as part one of four in a saga and an offbeat ‘science epic’ film about a futuristic architect will be difficult to market. That may sound like an unnecessarily reductive description of both films, but it’s how audiences tossing up between a night at the their local cinema and an evening on the couch will feel.

That leaves critical success, which, judging by initial reviews, will also be hard to come by. Perhaps wider audiences will love Horizon and Megalopolis and by awards season, they will have gained enough momentum to make a run for some hardware. That’s not to say self-funded films will catch on though, even in that hypothetical scenario. If the film industry valued critical success over commercial responsibilities, there’d be a lot more blockbuster Oscar winners like Oppenheimer, and a lot less superhero flicks. This rogue, director-funded model may very well die with Costner and Coppola.

Related:

Cannes film festival 2024: Which movies will we be arguing about this year?

What to stream in May: Netflix, Disney+, Stan, Amazon Prime + more