Why Akira Toriyama’s legacy goes beyond the epic story of 'Dragon Ball Z'

For many it was the pinnacle of breakfast TV. But 'Dragon Ball Z' taught a generation of young men how to train hard and fight for what you love.

I STILL REMEMBER the first time I tuned in to what was then the golden era of Channel 10’s morning kids show Cheez TV. It was late 2001. I’d just moved to Australia from England—needless to say an overwhelming experience for a young eight-year-old. But from that whirlwind month, two things left an indelible mark on my young psyche: the sumptuous decadence of double coat tim-tams, and a Japanese cartoon that, up until then, I’d never seen before. It was, of course, Dragon Ball Z.

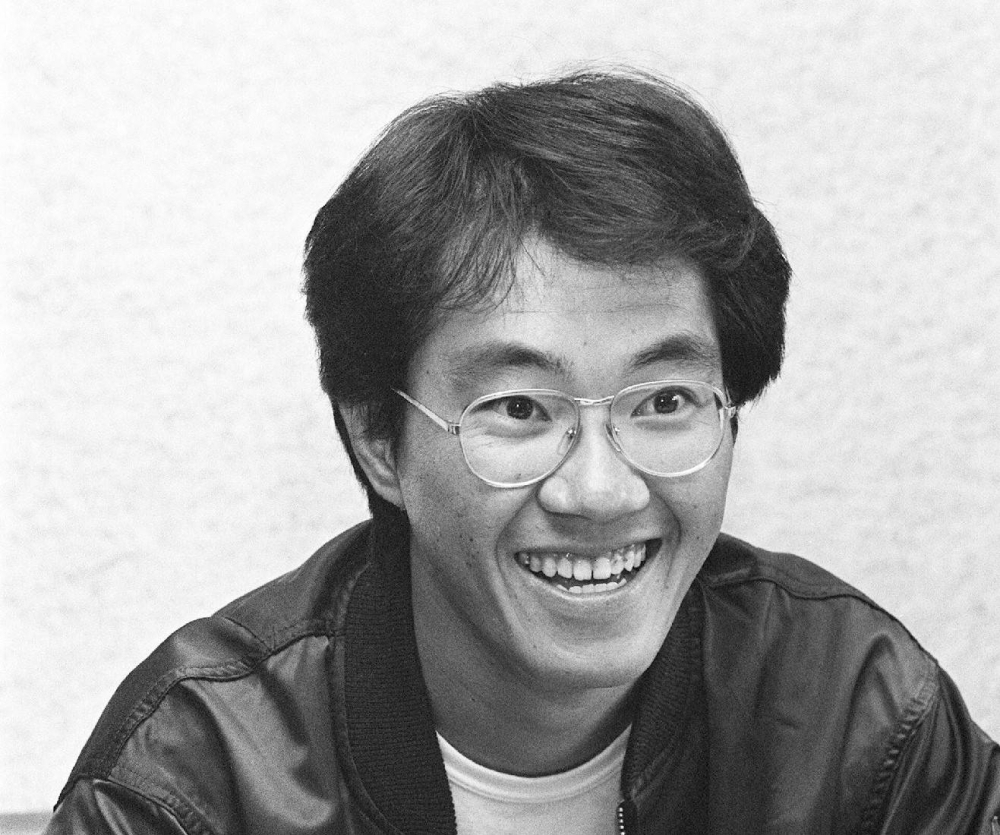

And what a time to tune in. As luck would have it, the first episode I caught happened to be the climax of a young Gohan’s epic duel against arch-villain Cell—still widely lauded as one of the most influential moments in anime. For an eight-year-old boy, seeing a character your age powering up to win a fight of apocalyptic significance was, naturally, intoxicating. But it was only as I grew into my teenage years (and let’s face it, adulthood) that I realised the impact the story created by Akira Toriyama, first in a wildly popular manga genre, and then as an anime beloved by millions, would ultimately have not just on pop culture, but an entire generation of young men. Which is why today, with the announcement of Toriyama’s sudden death at the age of 68, myself and many others will be feeling a potent cocktail of sadness and undeniable nostalgia.

By the standards of both manga and anime, Dragon Ball, and its most popular sequel series Dragon Ball Z and Dragon Ball Super, tell fairly conventional stories. They’re both the template and the epitome of what’s known as battle manga: a fairly formulaic method of storytelling defined by the protagonists’ protracted struggle against greater and more powerful villains. The great skill levied by Toriyama and co. was in their ability to toe the line between cartoonish hyperviolence, which held back just enough to keep the rating agencies approving content for kids’ TV happy, and a level of grandeur which exceeded even that of a Marvel movie: one where characters could punch each other through mountains and level entire planets on a whim. It turned what would have otherwise been a fairly middle-of-the-road Japanese cartoon into a pop culture phenomenon, redefining the West’s perception of anime as it did so.

Where Dragon Ball Z was revolutionary, however, was in its reflective, sometimes even spiritual approach to what would have otherwise been a very simple story about ever-grander contests of strength. For every bulging muscle and epic fight the show became renowned for, emphasis was placed on the training and work ethic it took its characters to achieve the power they had. The world-altering power obtained by Dragon Ball Z’s characters wasn’t the result of a mutation or a freak origin story: it came from hard graft. For me, that continues to be a near-endless front of inspiration, and given the near-mythic status characters like Goku and Vegeta hold among fitness enthusiasts and even pro athletes, I’m confident I’m not alone in that.

But it was in Dragon Ball’s softer moments, particularly, that Toriyama’s method of storytelling had perhaps its most pronounced impact. Dragon Ball was undoubtedly, unashamedly macho, but never wavered in the emphasis it placed on strong female characters, either as fierce, loving matriarchs like Chi-Chi and Bulma or ice-cold villains like Android 18. The familial bonds both the anime and the manga spent countless volumes and episodes building up leant its climactic moments an emotional weight that, while going over the heads of younger viewers amidst the epic transformations and the showers of cataclysmic energy blasts, continues to leave its now much-older fans misty-eyed.

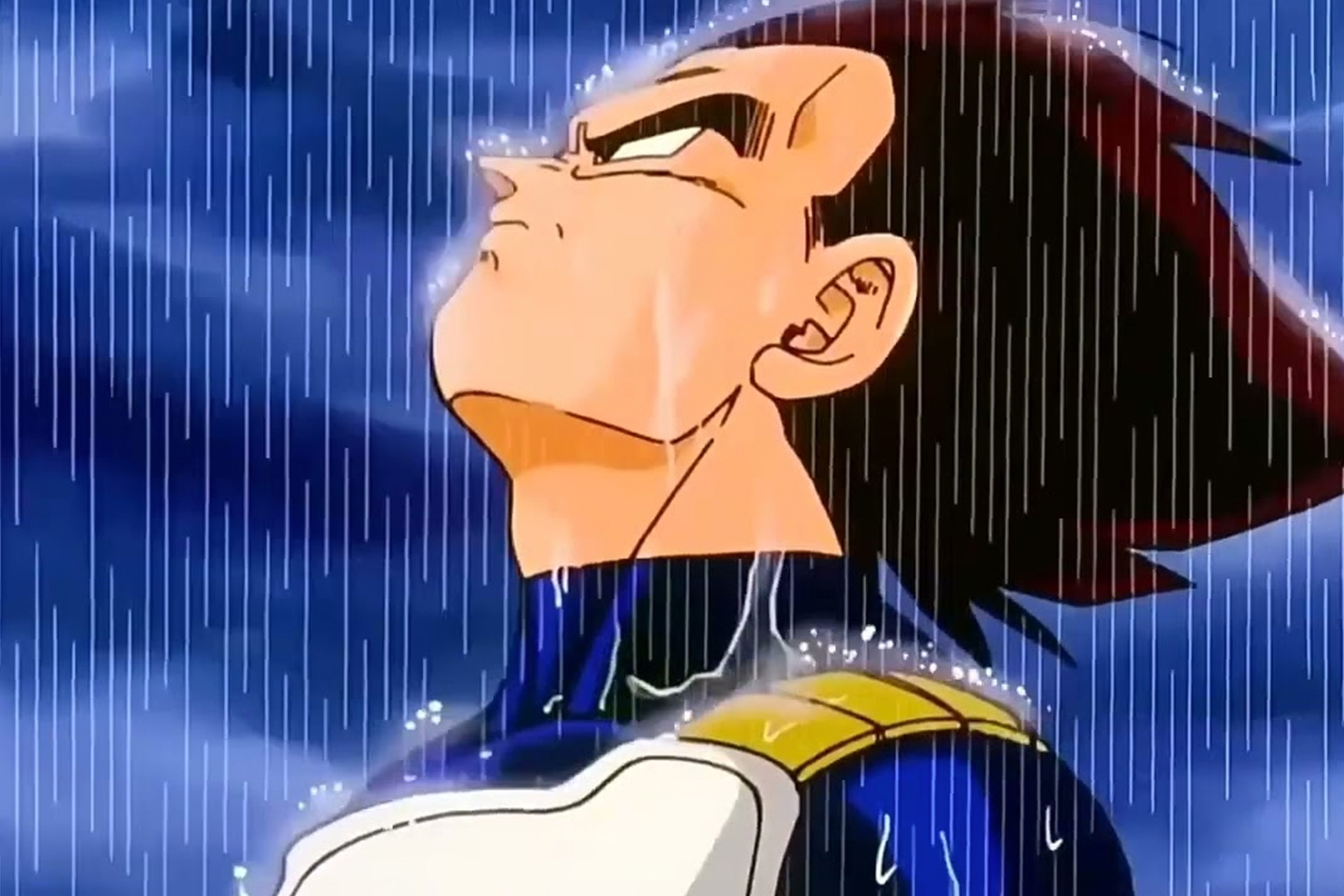

Where I think the most powerful legacy of Akira Toriyama lies, however, is in Dragon Ball’s expression of male emotion as a source of strength, rather than weakness, which became one of the show’s core themes. Goku’s iconic first transformation into the now world famous Super Saiyan came through a veil of tears, as did his son Gohan’s crowning moment in the episode I mentioned earlier. Even the show’s most emphatically stoic character, Vegeta, found his greatest strength unlocked when he finally learned to love. Dragon Ball, ultimately, is a story defined equally by physical and emotional battles. Perhaps Akira Toriyama’s most important achievement, then, was teaching us that it was not just okay, but powerful, to cry—even if we didn’t know it at the time.

Related:

Netflix is a goldmine of anime right now

The Nintendo Switch 2 is (probably) coming out within a year