The 38 greatest spy films of all time

The espionage movies every man should watch.

IN THE 1965 film The Spy Who Came In From The Cold, Richard Burton’s disgruntled secret intelligence officer Alec Leamas offers a choice appraisal of his profession: “What the hell do you think spies are? Model philosophers measuring everything they do against the word of God or Karl Marx? They’re not. They’re just a bunch of seedy, squalid bastards like me […] civil servants playing cowboys and Indians to brighten up their rotten little lives.”

Based on the book by John le Carré, Leamas is one of the many less-than-glamorous spies that populate the author’s work and their adaptations, from an out-dated, out-numbered and out of style Gary Oldman in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy to a haggard Philip Seymour Hoffman, giving one of his final (and greatest) performances as a German intelligence officer in A Most Wanted Man.

Here we’ve collated our favourite spy films of all time, from le Carré-style gritty realism to the outlandish espionage fantasises of Jason Bourne and (of course) James Bond, meaning there is something there for everyone – wherever your allegiances lie.

Tenet (2020)

The release schedule knackered by the pandemic and everyone’s ears were knackered from straining to hear what anyone’s saying through the haze of noise and rumbling which permeates the whole thing. (It was a deliberate artistic choice! Actually!!) Tenet was the first Christopher Nolan thinky-thriller to really split opinion. But with a little bit of distance, it all feels less like Nolan’s audition for a Bond film – though there were definitely nods and winks here and there – and more like a genre-bending attempt to launch a sensation straight into your brain. When Protagonist (yep) is recruited by a shadowy organisation which has the technology to manipulate time, he’s tasked with taking out the villainous Sator who wants to save the world by turning it all backwards and destroying it. Whether it makes sense and what actually happens in the end is the wrong question to ask; it’s really a mega-budget attempt to invert blockbuster cinema at large. Robert Pattinson wears some lovely suits too.

The Fourth Protocol (1987)

Received wisdom says that Michael Caine did not have a good Eighties. Jaws: The Revenge looms large in the collective memory, chomping Caine’s decade to bits. But there was a lot of good stuff in there: Bond director Terence Young’s underrated thriller The Jigsaw Man, Educating Rita, Mona Lisa, and this. It takes Caine back to the mid-Sixties milieu of his Harry Palmer character, and as MI5’s John Preston he’s equally insubordinate and troublesome to his betters. It’s a meeting of two eras of Brit spy actors too: Pierce Brosnan is ice-cold KGB officer Valeri Petrofsky, sent by Moscow to set off a false flag nuke on British soil and blame the Americans. Naughty.

Eye of the Needle (1981)

Richard Marquand got the Return of the Jedi gig after this taut World War Two thriller set in Scotland caught George Lucas’ eye. It’s an interesting reversal of the usual taut World War Two thriller though: it follows Donald Sutherland’s Nazi sleeper agent Henry Faber as he tries to get information about the upcoming D-Day landings back to his handlers in Germany via a U-boat rendezvous, but gets stuck on a tiny island as rough weather sets in. Faber starts putting the moves on a young woman named Lucy, but her husband starts getting suspicious of him sneaking film canisters around. Suffice to say, there’s a reason Faber’s known as ‘the Needle’, and it ain’t pretty – his preferred method of dispatching nosy parkers is stabbing them with a very thin knife. Yikes.

Charlie Wilson’s War (2007)

In 1980, Congress’s resident party boy Charlie Wilson is convinced that he should probably do a bit of good while he’s in government, and he starts rummaging around in Afghanistan and covertly funding guerrillas fighting against the Soviet Union. What could possibly go wrong? Well, Wilson ends up completely changing how America fought the Cold War, while also setting in train a series of events which leads, slowly but surely, to the reaping of a whirlwind. (Before Tom Hanks got involved, the final scene of the film was to be of the 9/11 attacks.) Don’t go into this light-footed caper expecting anything particularly historically rigorous – it’s pretty fast and loose with the facts – but Aaron Sorkin’s on script duties, Mike Nichols is behind the camera, and Hanks, Julia Roberts and Philip Seymour Hoffman head up a ludicrously stacked cast.

Spione (1928)

Fritz Lang laid much of the groundwork for the spy films which were to come later with his deeply atmospheric, paranoia-drenched early films. On the heels of the visionary but commercially disastrous Metropolis, Lang and his wife Thea von Harbou put together this low budget thriller to try and avoid the UFA studio cancelling his contract. Lang thought of it as “a small film,” but it’s big on action. When the German secret service sets about bringing down the head of an organised crime organisation, but the operative they put onto it falls in love with his quarry. Things ramp up with the theft of an international peace treaty, there’s a brilliantly tense train crash sequence, and the crescendo at a music hall clearly had an impact on Alfred Hitchcock – he riffed on it in The 39 Steps.

Sneakers (1992)

Sadly nothing to do with people who wear sneakers – for sneaking – but a star-stuffed techno-thriller which packs in Robert Redford, Ben Kingsley, Sidney Poitier, River Phoenix and Dan Aykroyd. Redford is a former radical socialist hacker who Robin Hooded funds to worthy causes, and who’s since formed a crack squad of white hat hackers who test out firms’ security. But when they chance on a black box which can crack open any computer system, they realise they’re in far deeper than they ever realised.

Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery (1997)

Almost as soon as James Bond became a sensation in the early Sixties, the particularly lurid version of spycraft and the underworld of espionage he represented was being spoofed. After Dirk Bogarde’s Hot Enough for June in 1964 came James Coburn in Our Man Flint, the first two Beatles films, Modesty Blaise, the Neil ‘brother of Sean’ Connery vehicle OK Connery and loads others besides. The Sixties loved Bond spoofs. Even The Flintstones got in on it. So it only made sense that the Nineties’ obsession with the Sixties would throw up its own postmodern spin on the genre. Cryogenically frozen in 1967, Austin Powers pitches up in 1997 to track down his old nemesis Dr Evil. An extremely Mike Myers kind of hilarity ensues.

Fantômas – À l’ombre de la Guillotine (1913)

This is the first part of five-film saga released across 1913 and 1914, and probably the earliest example of a straight-up spy film. It was based on a popular newspaper serial about the criminal genius Fantômas, who wears a black hood and leotard and sneaks about using any means to get what he wants. One of his nicknames is “master of everything and everyone” which feels appropriately spy film villainous. Inspector Juve (Edmund Bréon) and journalist Jerôme Fandor (Georges Melchior) are on his tail though. Many of the spy film ingredients are here: lurid bad guy; improbable escapes; international settings; and a conspiracy which just goes deeper and deeper.

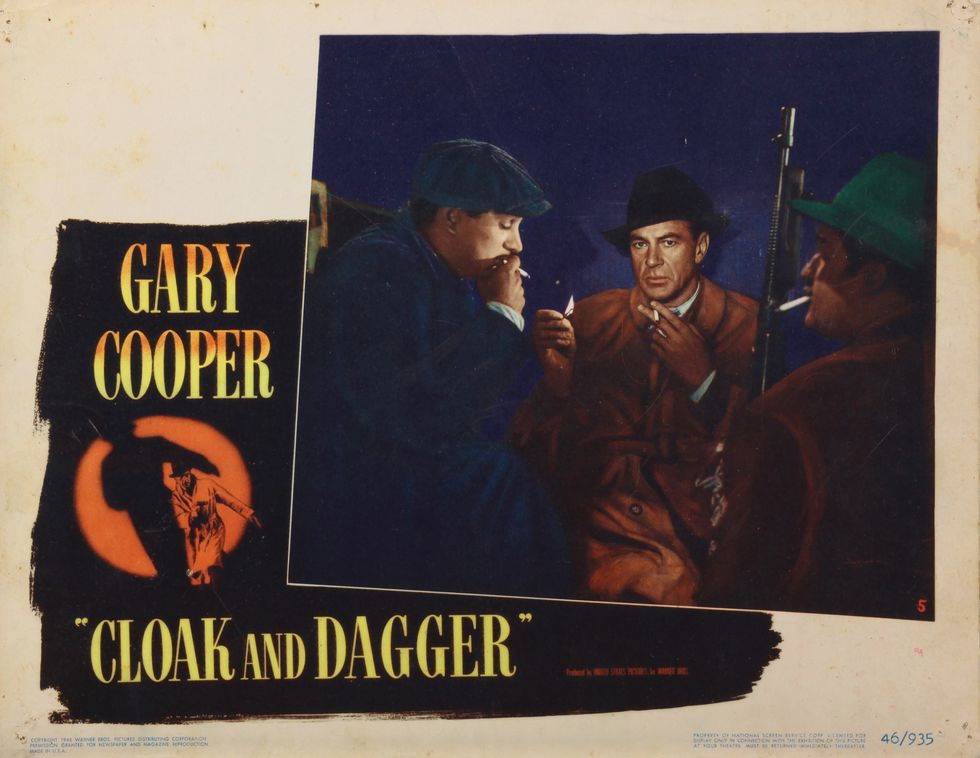

Cloak and Dagger (1946)

When Fritz Lang was offered a role as head of the German studio UFA by Joseph Goebbels, he fled to Paris and then to Hollywood, afraid his Jewish heritage would put him in danger. By the end of the war, he’d find Cloak and Dagger being attacked for being apparently too Communist – the final reel of this nuclear intrigue about keeping the secrets of the bomb out of enemy hands was changed by producers and its writers blacklisted. Gary Cooper is the dashing physicist who falls for Lilli Palmer’s resistance fighter Gina while trying to sort those ruddy Nazis out.

Mata Hari (1931)

The only drawback of a biopic about Mata Hari – the Dutch dancer, courtesan and accused spy who was executed by France during World War One – is it could never really touch the reality of Hari’s life for drama. Greta Garbo’s portrayal does give it a fair crack though. It goes all in on the idea that Hari really was a spy (Hari herself denied it, and she may have been as much a handy French scapegoat as a useful German asset) and used her glamorous wiles to steal secrets for Germany. Garbo was rarely more magnetic and sultry than here, where the conflation of sex and spying first really took hold.

The Lady Vanishes (1938)

The last stretch of Alfred Hitchcock’s run of British-made films up to 1940 returned again and again to the spy thriller. The 39 Steps, Secret Agent and Sabotage are all varying degrees of great – especially the magnificent The 39 Steps, on which more below – and very few films in any genre can top North by Northwest, but none of them are as breezily charming and psychologically twisty as The Lady Vanishes. Somewhere in central Europe, a young bride-to-be called Iris takes a plant pot to the head and meets an old lady called Miss Froy and a young, annoying man called Gilbert before jumping on a train. Iris and Miss Froy get friendly, but then suddenly she’s nowhere to be found. Was she ever there? And if so, who wanted to get rid of her? Espionage, nuns, a whistled musical motif and a train-based shootout ensue. And, in the cricket-mad Charters and Caldicott, it minted the ultimate in doddering comic relief duos.

A Most Wanted Man (2014)

We’re going to see quite a few John Le Carré adaptations here, and there have been a lot of extremely decent ones. They tend, though, to crystallise a particularly Cold War froideur: the ‘good’ guys defending the West and its grubby morality against monsters beyond the Iron Curtain who looked disconcertingly like themselves. A Most Wanted Man is a post-9/11 story set in Germany, where Philip Seymour Hoffman’s Günther Bachmann and his covert team try to turn dissidents with ties to terrorist cells into informants and gradually turning whole chains of command to their side. At the same time, a hardline duo called Mohr and Sullivan are on the tail of a potentially useful source. As ever in Le Carré’s stories, loyalties are tested and morality is greyer than grey, and a stellar cast including Willem Dafoe and Rachel McAdams lifts everything.

The Conversation (1974)

Famous for his surveillance expertise, Harry Caul is the go-to guy for corporations who want to spy on their rivals and, if necessary, their own employees. Gene Hackman’s Caul is a man obsessed with his own privacy, and one of most memorably tragic lead characters in cinema. When he suspects the couple he’s spying on will be murdered, his religious faith causes him to suffer a crisis of confidence. In contrast to director Francis Ford Coppola epics, The Godfather and Apocalypse Now, the tone is pared back, tightly edited and claustrophobic. In other words, the perfect spy movie atmosphere. Coppola stated that the parallels with the contemporary Watergate scandal were coincidental.

The General (1926)

Yes, the one about the train. You’ve seen the bit where Buster Keaton bonks a railway sleeper out of the way with another railway sleeper; watch the whole thing, though, and you’ll see it’s a proto-spy film. The spy just happens to be being played by the most gifted comic actor who ever lived. Desperate to sign up for the Confederates during the American Civil War to impress his beloved – yeah, not a tremendous decision – Keaton’s train driver Johnnie finds himself spurned when he’s turned down for service.

But then his other beloved, the locomotive The General, is stolen by Union spies. He gives chase in another loco, and a series of increasingly spectacular stunts and set pieces ensues. The General might be a comedy, but the way that it pitches an ordinary man into a dangerous political intrigue is pure spy thriller material, and Keaton’s commitment to his own wildly dangerous stunts echoes in Tom Cruise’s eye-boggling latter-day Mission: Impossible work. Keaton reflected toward the end of his life that he “was more proud of that picture than any I ever made.”

Atomic Blonde (2017)

Charlize Theron is MI6 agent Lorraine Broughton, who on the eve of the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 is roped into the office to explain her recent work in the city. A microfilm containing the names of every agent on either side of the Iron Curtain at work in Berlin has been stolen, and she’s dispatched to bring it back. Atomic Blonde isn’t particularly original, but its pulpy, splenetically violent action sequences and the cantankerous buddy-up between Theron and James McAvoy make it more than worth your time.

Citizenfour (2014)

A thoroughly modern spy movie. Filmmaker Laura Poitras serves as director and confidant as she interviews whistleblower Edward Snowdon over eight days in a Hong Kong hotel room, work that would lead to the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service. The revelations over how widespread US surveillance of its own citizens is have lost none of their shock, and as Snowden, Poitras and journalist Glenn Greenwald discuss how they will drop their bombshell on the world, this is as nervous and gripping a watch as anything with John le Carré’s name attached to it.

Top Secret! (1984)

An under-appreciated Zucker-Abrahams-Zucker movie that does for the spy genre what Airplane! did for the airport disaster movie. That is, send it up with unhinged relish. The plot, such as it is, concerns American rock star Nick Rivers (a superbly blank Val Kilmer) being dispatched to East Germany during the second world war to perform at a festival, only to find himself caught up in an underground resistance movement. It’s also a musical, and an Elvis parody. The silliness is infectious. “I know a little German. He’s sitting over there.” “What phony dog poo?” “I know… it all sounds like some bad movie”. When it came out the audience voted with their feet and went to see Gremlins instead. It flopped spectacularly.

The Ipcress File (1965)

“[Harry Palmer] had my attitude to authority: screw it, I’ll do it my way and get it right. A rebel.” So said the great Sir Michael Caine during an interview with Esquire, and we’d have to agree that he’s on to something. For Palmer, service in the MOD is a penance of sorts for his criminal exploits while in the British Army, rather than a career plan. Released in the same year as Sean Connery’s fourth Bond outing, Thunderball, Caine’s Harry Palmer is the anti-007. He shops in supermarkets, likes cooking (omelettes are a speciality) and wants a pay-rise so that he can upgrade his kitchen utensils. Tasked with investigating the brainwashing of sixteen British scientists, Palmer is kidnapped and subjected to the IPCRESS conditioning method, in an attempt to turn him into a double agent. Resisting the process, Palmer purposefully subjects himself to pain while chanting one of Caine’s most iconic quotes: “My. Name. Is. Harry. Palmer!”

No Way Out (1987)

The voice-over in the trailer for Kevin Costner and Gene Hackman’s thriller about a US Naval officer investigating a murder is pure eighties overkill. The plot, however, still stands up as one of the best spy films committed to film, with Gene Hackman turning in an on-the-money performance as the Secretary Of Defence trying to shift the blame for his promiscuous wife’s murder away from himself and on to a rumoured Soviet sleeper agent named Yuri, while tasking Costner – the other man in the affair – to investigate. Called “truly labyrinthine and ingenious” and a “superior example of the genre” in the late, great movie critic Roger Ebert’s original review, it’s Hackman and Costner’s performances that elevate this to a classic. For anyone disappointed with the lacklustre Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit, this is the film to watch to see Costner playing the spy game properly.

Bridge of Spies (2015)

After the none-more-gritty Munich, Steven Spielberg returned to Cold War politicking – but this time he took Tom Hanks and Mark Rylance with him, the latter on career-high form. Hanks is James B Donovan, an insurance lawyer who is drafted in as a patsy to defend Soviet spy Rudolf Abel (Rylance), but sticks to his principles and helps him avoid the death sentence. A few years later, US airman Gary Powers’s U2 spy plane is shot down over Russia and Donovan is tapped up by the Soviets to help with a possible prisoner swap for Abel.

It’s more a character study in the patiently constructed Le Carré mould than it is a no-holds-barred set-piece-driven adventure, which gives Rylance room to quietly and drily earn your sympathy. It looks absolutely glorious too, and with Joel and Ethan Coen helping out on script duties, there are a lot more laughs than in most spy thrillers set in the GDR.

Burn After Reading (2008)

Spy parodies tend to send-up the slickness of secret agents, the vanity of super villains and other Bond-inspired movie tropes. The Cohen Brothers’ star-studded farce Burn After Reading, however, aims its satire at the paranoid incompetence of so-called intelligence agencies, and the scheming dunces who fall foul of them in search of an easy dollar. Think Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy crossed with Four Lions, and… you’re still pretty far away, actually. Just watch it, why don’t you? It’s just as funny now as it was upon release twelve years ago, and the never ending Russiagate debacle only adds prescience to the film’s Cold War mindset.

The set-up: Osbourne “Ozzie” Cox (John Malkovich) quits his job as a mid-level CIA operative to write a memoir. Meanwhile, in a bid to secretly begin divorce proceedings, his wife Katie (Tilda Swinton) downloads his financial records onto a disc to give to her lawyer – but accidentally copies his memoir draft over too. Not long after that, the lawyer in question inadvertently leaves the disc at her local gym, where it’s discovered by two clueless chancers in the form of Linda Litzke (Frances McDormand) and Chad Feldheimer (Brad Pitt). What follows is a tangled web of blackmail, sex, subterfuge, murder and boundless stupidity. The only good decision in the entire film is George Clooney’s beard.

Mission: Impossible – Fallout (2018)

The M:I series pivoted from being a trilogy with one great film to an all-conquering action juggernaut over the course of the 2010s, but it’s easy to forget while you’re watching Tom Cruise fling himself about on the Bhurj Khalifa that he’s supposed to be a spy. He’s a spy though, and a spy for the IMF at that. (That’s the Impossible Mission Force, not the International Monetary Fund.)

In probably the best of all the Mission: Impossible films, he has to stop terrorists cobbling together nuclear bombs with stolen plutonium. That’s not the point, though. The point is that Cruise is very obviously doing all the staggering stunts himself, including the much-vaunted HALO jump sequence. He actually jumped out of a plane 106 times to get the freefall shots, and Fallout finds new ways to channel that visceral rush brilliantly. Angela Bassett, Vanessa Kirby and Henry Cavill’s Moustache join Cruise alongside a roll call of stars from previous impossible missions.

Enemy of the State (1998)

This update of those post-Watergate Robert Redford political thrillers – films which question whether you can trust the organisations that are meant to be looking out for us – places it squarely in the mass surveillance era. The National Security Agency has murdered a prickly congressman who’s being a big nerd about their plan to spy on everyone, but the whole thing’s caught on video.

The footage is planted on district attorney Robert Dean Clayton (Will Smith), and the NSA sets about destroying his life. So, in the classic Hitchcockian mode, he’s got to clear his name and work out what the hell’s going on. It’s less subtle than those mid-Seventies films, but it barrels along and has the enormous draw of a particularly splenetic late-period Gene Hackman, who spends much of his screen time screaming at Smith while looking out for his beloved cat.

Argo (2012)

In the sub-genre of ‘spy films where normal people have to do some spying’, Argo stands apart. Ben Affleck shares top billing with Ben Affleck’s Magnificent Beard in this one, based on the true story of a film crew who had to help bust some American hostages out of Tehran. They didn’t use dead drops or jetpacks or a watch with a laser in it. They pretended to make a fake sci-fi fantasy adventure Star Wars rip-off called Argo and smuggled in some Canadian passports.

While it’s a consummate spy thriller, it manages to bend toward being a heist caper too, with some top turns from John Goodman, Bryan Cranston, and particularly Alan Arkin as the cantankerous, veteran film producer Lester Siegel. Don’t like the fact that it beat Lincoln to the Best Picture Oscar? Argo fuck yourself.

Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (2011)

The set-up is simple: “There’s a mole, right at the top of the Circus,” John Hurt’s MI6 spymaster Control tells Gary Oldman’s George Smiley as he tasks him with catching a traitor leaking secrets to the Soviets. All the key le Carré themes are here in this stripped-down but unhurried take on the novel – loneliness, frailty, decline – and Oldman’s vast armoury of tiny facial flinches and tics make him stand out even in an ensemble of Britain’s more cerebral leading men: alongside Hurt, there’s Benedict Cumberbatch, Tom Hardy, Colin Firth and Mark Strong. The grimy, grotty, shambling Britain of the 1970s is brilliantly evoked, the tailoring is impeccable, and the final montage, set to Julio Iglesias’ version of Somewhere Beyond the Sea, is as satisfyingly elegant a cinematic conclusion as you’ll see.

The Bourne Identity (2002)

Loosely based on Robert Ludlum’s story of an amnesiac spy, Doug Liman’s Bourne Identity pressed the re-set button on the entire genre, with Daniel Craig‘s Bond films and even Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy taking inspiration from Bourne’s brutal, close-quarter’s combat style and gritty, rain-soaked locations. It was also the film that made us take Matt Damon – the angry kid from Good Will Hunting and the stoner-angel from Dogma – seriously as a fully-fledged Hollywood leading man.

The Imitation Game (2014)

It turns out it’s not just the invention of the computer that we can thank the real-life Alan Turing for, but also, in part, the Allied win in World War II. Benedict Cumberbatch stars as the code-cracking Turing and this engaging, Oscar-winning film reimagines the story of when Turing worked at Bletchley Park and invented a machine – which he calls Christopher – to uncover the Nazi’s attack plans. However, there’s a dark agent in the cryptography department; boo, hiss, it’s John Cairncross (Allen Leech), who threatens to out Turing when he discovers his own secret that puts national security at risk. It’s a bitter ending though, when you realise that Turing was never honoured for his work during the war, and took his own life after being convicted of gross indecency and chemically castrated for being gay. The film goes a small way to redress the balance of his remarkable life, and may have been an inspiration for Queen Elizabeth II giving Turing a posthumous Royal Pardon.

The Men Who Stare At Goats (2009)

When Jon Ronson sat down to write The Men Who Stare At Goats – a non-fiction book exploring the US government department of psychic spies that were apparently used for special ops throughout the years – there’s no way he could have imagined it would end up as a Hollywood film featuring George Clooney, Brad Pitt and Ewan McGregor in the starring roles. But then, as Ronson well knows, the truth is often stranger than fiction. This farcical and highly enjoyable caper takes a Coen-brothers-era Clooney (“I’m a Jedi warrior”! Clooney-as-Lyn-Cassady, announces to McGregor-as-Ronson) who details how he and a band of men, the New Earth Army, could make a goat’s heart stop just by staring at it hard enough and were sent out to bring about world peace. Set largely in Iraq with the backdrop of the Iraq war, the exploration of this little-known bizarre squad and its history in the US army works as a fitting counterpoint to highlight the absurdity of war itself.

Notorious (1946)

Alfred Hitchcock at his most hard-boiled, this Cary Grant-Ingrid Bergman double bill about the daughter of a Nazi war criminal recruited to infiltrate a ring of Nazis in Brazil became famous for the scene in which Hitchcock slipped around Hollywood’s ban on kissing scenes over three seconds – by having the actors break the kiss every few seconds before continuing. However, it’s Grant’s wardrobe that we’re most interested in, particularly his flawless dinner jacket, preceding a certain spy with a penchant for bow ties and tuxedos by almost 20 years.

The 39 Steps (1935)

Few films made Orson Welles gasp, “Oh my God, what a masterpiece.” The 39 Steps, named the fourth best British film of the 20th century by the BFI, is one. In only Hitchcock’s second spy film, released a year after The Man Who Knew Too Much, Robert Donat plays Richard Hannay, an innocent man accused of murder who can only clear his name by uncovering an evil cabal called the 39 Steps. Stylish, relentlessly pacy and revolutionary in its time, Hitchcock soups up John Buchan’s novel with daring set pieces – most famously Hannay’s scramble along the outside of the Flying Scotsman and escape onto the Forth Bridge – and adds an erotic charge by shackling the hero to the director’s first icy but irresistible blonde female lead, played by Madeleine Carroll. Hitchcock’s first great thriller introducers the key ingredients of all that were to come: an honourable man caught in a shadowy behemoth’s web; the McGuffin of what the 39 Steps are to keep the action sprinting along; and, most of all, a playful manifestation of the claustrophobic, obsessive relationship with sex he’d return to later in Psycho, Frenzy, Marnie and Vertigo.

Three Days Of The Condor (1975)

Almost deserving of its place on this list because of its style alone (those suits, that knitwear, that peacoat) Sydney Pollack’s 1975 thriller about a CIA researcher who comes back to find his unit dead is quite possibly Robert Redford‘s best role. Out of his comfort zone as the cockey leading man, Redford turns in a stellar performance as he runs from both the CIA and a string of mysterious killers, with Max Von Sydow ticking the ‘evil assassin in tan trenchcoat’ box.

From Russia With Love (1964)

Of course we’re not saying Connery’s second outing is the best Bond film of all time (although there’s a strong case to be made for it) but, in terms of good old fashioned espionage, you’d be hard-pushed to beat Bond’s exploits with SMERSH and super Soviet assassin Red Grant (a stone cold Robert Shaw). From poisoned toe-spikes to taking down a helicopter with a rifle cobbled together from a briefcase, this is the film that set the tone for Bond films to come. The best scene of course is Bond’s tense after-dinner fight with Red Grant aboard the Orient Express, followed by Bond’s pithy one-liner as he takes in the body of the dead Russian, “Red wine with fish. I should have known.”

Spy Kids (2001)

Some readers might baulk at the inclusion of a family-friendly caper in this Very Serious List. But Spy Kids, fun, frenetic and fantastical as it may be, is genuinely up there with some of the most accomplished espionage movies ever made. You’d expect nothing less of writer/director Robert Rodriguez, the celebrated writer/director behind Sin City and From Dusk till Dawn, who always had respect for the taste and intelligence of his youthful target audience. “I wanted this to have the feel like a kid wrote it,” be told Creative Screenwriting in 2015. “Shot it, edited it, directed it. What a kid would do […] I was so inspired by those kinds of movies when I was growing up, and they weren’t making them anymore.”

It begins with a simple premise: what if your seemingly humdrum mum and dad were secretly international spies? Once upon a time, Gregorio (Antonio Banderas) and Ingrid (Carla Gugino) were sent on a mission by their respective intelligence agencies to assassinate each other, but ended up falling in love, retiring and starting a family. All’s well that ends well. But then a spate of disappearances force them to return to action twelve years later, and they soon join the long list of MIA agents. Needless to say, it’s left up to their children, 12-year-old Carmen and 9-year-old Juni, to save the day.

While Spy Kids is undoubtedly the strongest instalment in the four-part franchise, Spy Kids 2: The Island of Lost Dreams features a line (from Steve Buscemi’s frazzled scientist Romero) so unexpectedly poignant that it deserves a mention: “Do you think that God stays in heaven because he too lives in fear of what he has created?”

Zero Dark Thirty (2012)

Kathryn Bigelow’s Oscar winning exploration of the CIA’s obsessive hunt for Osama Bin Laden made a star of Jessica Chastain and was celebrated as one of the most intelligent spy thrillers of all time. Like Homeland turned up to eleven, Zero Dark Thirty brought the reality of torture, military base bombings and al Qaeda to a viewing public that had only previously read about them in broadsheets and limited published accounts. This is a spy film that dispenses with the glamour to show us that spy work is dirty work and the chilling fact that those searching for the truth are often just as clueless as the rest of us.

North By Northwest (1959)

Tied with Vertigo for the title of ‘Hitchcock’s greatest film’, North By Northwest is the original anti-spy spy film. It’s an espionage tale told from the perspective of the innocent as Cary Grant‘s advertising executive Roger Thornhill goes on the run from a shadowy organisation in a case of mistaken identity. There’s lots to get excited about here, from Thornhill’s devotion to a good suit to the epic finale atop a soundstage Mount Rushmore, not to mention to film’s fantastically hard-boiled dialogue: “I’ve got a job, a secretary, a mother, two ex-wives and several bartenders that depend upon me, and I don’t intend to disappoint them all by getting myself ‘slightly’ killed”.

Most conversations about the film tend to focus on the now iconic crop-duster scene (in which Thornhill finds himself in the middle of corn fields, with nowhere to hide as a belligerent pilot swoops down on him) and with good reason – it’s testament to Hitchcock’s ingenuity that a scene so simple – one that eschews the piranha-filled pits, laser beam vasectomies and exotic locals of Bond for a mid-western farmer’s field – still holds up as one of the most menacing chase sequences in film history. All told, North By Northwest remains an iconic film from one of history’s most iconic directors.

The Lives Of Others (2006)

Five years before Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy did dreary Cold War drama, The Lives Of Others gave us a glimpse behind the Iron Curtain and over the Berlin Wall into 1980s Soviet-occupied East Berlin in a drama that documented the Big Brother-esque observations carried out by the Stasi (the German Democratic Republic’s secret police). The film focuses on the surveillance carried out on a German playwright, Georg Dreyman who writes an anti-government article after his friend commits suicide. Told from the perspective of the Stasi official tasked with monitoring Dreyman, The Lives Of Others offers a truly grim glimpse into what it was like to be a spy during the Cold War, particularly if you didn’t necessarily believe in the cause you had devoted your life to.

Produced and directed in Germany, the film does away with Hollywood pretences at a happy endings and silver linings – nothing particularly cheerful happens here, from the daily paranoia of both the observers and the observed to the harrowing final scenes involving Dreyman’s young actress girlfriend. Nor is any character entirely likeable. Dreyman is free-spirited but a devout communist, while Stasi spy Wiesler attempts to suppress evidence on the playwright while condemning countless others to prison or worse. An outstanding film about the grey area lost to the West behind the Berlin Wall and the grey moral ground its inhabitants are forced to inhabit in order to survive.

The Third Man (1949)

Touted as “the first great picture of 1950” and selected by the BFI as the “best British film of the 20th century“, this tale of murder and smuggling in Allied-occupied Vienna remains one of the most stylish thrillers of all time. From the famous “cuckoo clock speech” scene on the Wiener Riesenrad big wheel to Orson Welles’ supposedly dead black marketer Harry Lime emerging from a shadowy doorway, to the final chase through the city’s cavernous sewers, The Third Man is a film that has often been imitated, but never bettered. Much to its producers distain, director Carol Reed insisted on shooting the majority of the film on location in post-war Vienna, and the piles of rubble and bomb craters that help define the film’s almost apocalyptic appeal are real

Scripted by Graham Greene (who occasionally worked as a spy for the British government) the dialogue is to kill for, with a character named Major Calloway warning the film’s inquisitive protagonist to “Leave death to the professionals”. All of these elements combine to make The Third Man without a doubt the best spy movie of all time, and according to many, including Roger Ebert, one of cinema’s greatest accomplishments, “Of all the movies I have seen, this one most completely embodies the romance of going to the movies.”

This story originally appeared on Esquire UK

Related:

The most stylish films of all time

The snubbing of Lily Gladstone and the Oscars complicated history with Indigenous people