The murky path to becoming a New York Times best seller, explained

Publishing insiders tell Esquire why they find "the list" so frustrating — turns out, it's a data project full of contradictions.

*indicates that a name has been changed at the request of the source

ANYONE WHO’S WORKED for a major book publisher in recent memory knows the energy that crackles through the office at 4:59 P.M. on Wednesday afternoons, right before the preview of next week’s best seller list arrives from The New York Times. After months of pitching reviews, planning marketing campaigns, doing bookseller outreach, and begging for budget, this is the moment when you find out if it was enough to earn your author a spot on the best seller list.

The New York Times best-seller list debuted in October 1931, reporting first on the top-selling titles in New York City before expanding in 1942. Over the years, what’s known in the industry as “the list” has come to comprise eleven weekly and seven monthly lists, covering paperbacks, audiobooks, and e-books (combined with print sales), as well as separate lists for children’s books, business titles, and more.

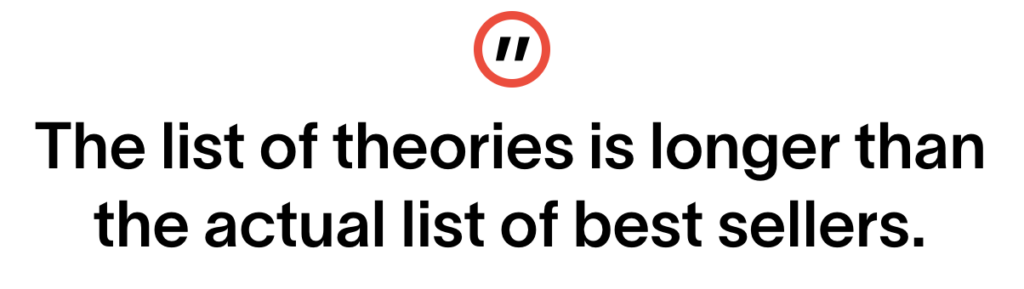

No one outside The New York Times knows exactly how its best sellers are calculated—and the list of theories is longer than the actual list of best sellers. In The New York Times’ own words, “The weekly book lists are determined by sales numbers.” It adds that this data “reflects the previous week’s Sunday-to-Saturday sales period” and takes into account “numbers on millions of titles each week from tens of thousands of storefronts and online retailers as well as specialty and independent bookstores.” The paper keeps its sources confidential, it argues, “to circumvent potential pressure on the booksellers and prevent people from trying to game their way onto the lists.” Its expressed goal is for “the lists to reflect what individual consumers are buying across the country instead of what is being bought in bulk by individuals or associated groups.” But beyond these disclosures, the Times is not exactly forthcoming about how the sausage gets made.

Laura B. McGrath, an assistant professor of English at Temple University who teaches a course on the history of the best seller, compares The New York Times’ list to the original recipe for Coca-Cola: “We have a pretty good idea of what goes into it, but not the exact amount of each ingredient.”

Kathleen Schmidt, president of KMSPR, a book publicity and marketing firm, speculates that The New York Times’ main data sources are Amazon, ReaderLink (a distributor for big box stores like Target, Walmart, and Hudson News), individually reporting stores, and BookScan (one of publishing’s main data providers). The Times denies the use of any services that aggregate data, but according to Schmidt, those in the industry believe otherwise. “I can’t imagine they do not use BookScan at all. They can’t simply rely on the individual stores,” she said.

Eloise*, a book publicist I spoke to who spent several years working within the Big Five (the five largest publishing houses: Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, Simon & Schuster, Hachette, and Macmillan), theorized that The New York Times seems “to look for signs that a book is selling large quantities organically — that is, individual copies being purchased from a variety of booksellers… with an emphasis on independent bookshops and geographic diversity.”

She also believes that The New York Times uses data from BookScan, employing it to flag books with a large percentage of bulk orders that might detract from the paper’s mission to represent individual consumer purchases.

Related: On the rise of short books

Although the list claims to be a numerical ranking with full autonomy from The New York Times Book Review, some of the sources I spoke with believe that an element of editorial curation must be at play. “To my knowledge, The New York Times tracks sales of books, and the sales are what is ‘supposed to’ decide where those books sit on the list. However, the truth is, it’s much more editorialised,” Sarah*, a book publicist who has worked at two Big Five houses, suggested to me. “There is quite a bit taken into consideration — i.e., are the book sales mostly bulk buys? Are they mostly indie bookstore sales? Are they mostly Amazon sales? Even which list the book would be considered for has a huge effect.” For example, whether a book is considered for the Hardcover Nonfiction weekly list or the Advice, How-To, & Miscellaneous weekly list might affect whether it becomes a best seller at all.

Sarah went so far as to suggest that the Times’s curation goes beyond a preference for books acquired at independent retailers — a theory posited by many I spoke to. “It’s frustrating when you get the actual numbers of what every book on the list sold and a book with lower numbers is higher on the list,” she said. “You know it’s because of connections or The New York Times preferring one read over another.”

Times spokesperson Melissa Torres denied in an email that any editorial judgments are involved in constructing the best seller list.

Tracy*, a freelance book publicist who used to work for a book public relations firm, also said that, in her experience, publicly available sales data doesn’t line up with what appears on The New York Times best-seller list. She said, “In the past, when I had access to BookScan, I sometimes did an exercise with authors where I’d show the sales figures for the books on the list in any given week. They often did not correspond to the position on the list—for example, the #5 book on the list may have sold fewer copies than the #9 book on the list.”

Asked why such a scenario might occur, Torres said, “As always, raw sales are only one factor in determining if or where a book might rank on our lists,” and directed Esquire to the best sellers methodology statement.

Like everyone I consulted, Tracy and Sarah both acknowledged that there’s no surefire way to know the list’s recipe. This is one of the reasons why those inside the publishing machine find The New York Times best-seller list so frustrating — it’s a data project full of contradictions.

OUTSIDE THE WALLS of The New York Times, making a book into a best seller can become quite a convoluted endeavor. And despite The New York Times’ claim that the paper doesn’t make its data sources public “to circumvent potential pressure on the booksellers and prevent people from trying to game their way onto the lists,” everyone I spoke to argued that attempts to game the list are as frequent in book publishing as new Danielle Steel novels.

Many of these tactics involve generating sales at reporting retailers before or right at the time of publication, thus making sure that those sales count toward the list. Any book purchased prior to its on-sale date is entered into the system on publication day and counted toward the week-one sales total, which means that racking up preorders is one of the best ways to ensure that a book debuts on the best sellers list. As soon as the retailer product pages go live (approximately six to eight months in advance of publication), the race is on to generate as many book sales as possible before the week-one window closes. This is one reason why so many books fall off the list after only one week — because there’s no ongoing sales momentum once all the preorders are placed. Torres confirmed as much, telling Esquire, “This is why books frequently stay on our lists for only a week or two and drop off, instead of climbing up and walking down the lists more gradually as they did decades ago.”

“If you’re an author that has an established platform where you’re in the media, you’re a frequent podcast guest, and have quarterly speaking engagements, then you have the exposure to generate sales through the months leading up to your publication date,” said Dawn Michelle Hardy, an independent publishing consultant and founder of the Literary Lobbyist. She points out that authors on the paid speaking circuit are able to negotiate the purchase of books into their honorarium package in lieu of a standard speaking fee, thereby driving up their best seller chances. Say an author does fifteen 300-person speaking gigs in the six months before their book goes on sale — that’s a 4,500-book head start on publication day.

To ensure that these books are counted toward the list, authors make arrangements for the sales to be channeled through a reporting source — like an independent bookstore. Eloise explained how, in the case of an author who negotiated book sales in lieu of their speaking fee, “the author would have those books purchased through various indie booksellers who specialise in business-to-business sales (i.e., [the indie] would get the sale, but [the book] would ship directly from the warehouse to the event).”

Authors who don’t go through that subterfuge (or whose tactics are detected) get a telltale dagger symbol under their name on the best-seller list, signifying that institutional, special interest, group, or bulk purchases were included at the discretion of The New York Times Best-Seller List Desk. The dagger doesn’t always mean that someone weaselled their book onto the list, but it’s a helpful tool for consumers to identify which books might have had a helping hand.

Preorder incentives are another method that authors and publishers regularly employ to juice week-one sales. These incentives range from basic (get a sneak peek at the book’s first chapter) to charming (get a hand-drawn illustration by the author) to downright cunning (get a second copy of the book free for your friend — a ploy to double the book sales). But with the exception of something as gauche as Gary Vaynerchuk giving an NFT to anyone who pre-ordered twelve copies of his 2021 book Twelve and a Half, preorder incentives are usually more strategic than outright obnoxious, so long as individual customers are the ones making the preorders.

Related: Will Drake’s new book get more men reading poetry?

FOR AUTHORS WITH deep pockets and big egos, there are companies they can hire to manoeuvre their way onto the list — or at least try. According to the sources I spoke to, a company called Book Highlight is known for running these “best seller campaigns.”

Book Highlight markets itself as “a performance-driven, full service agency dedicated to increasing the audience and impact of authors and their books.” Some in the industry believe that Book Highlight is actually just a rebranded version of ResultSource, a marketing firm that had a bad run of press in the 2010s for its alleged methods of pushing books, including some from the religious right, onto the list.

“They don’t advertise this outright on their website, of course, but authors can pay for them to purchase a certain number of books in a way that supposedly looks to be ‘organic’ sales,” explained Tracy, who has worked with authors who have hired Book Highlight. “As I understand it, an author will pay for X quantity of their own book and the cost of Book Highlight’s services. Book Highlight will then purchase the books from different retailers in low numbers and they will be shipped to a Book Highlight distribution centre. From there, the author can either sell or give those books to organisations who want to purchase them for events.”

Book Highlight did not respond to a request for comment on the details of its service and its alleged relationship to ResultSource.

While the impetus and funding for best seller campaigns from Book Highlight or any other such company comes mainly from authors, that doesn’t mean that publishers aren’t well aware of this practice.

“Although publishers do not employ this company or work with them, their knowledge and tacit compliance is necessary,” Elliot*, a Big Five book publicist with more than fifteen years of experience, told me. “Namely, publishers need to know in advance that there will be an entity out there buying up thousands of copies of books in order to print enough to satisfy the demand.” I can tell you from nearly a decade spent working at the Big Five — these campaigns aren’t a secret to those inside the publishing machine.

Some authors even forgo the consultant and handle the best-seller campaign on their own. “I’ve had authors who send other people to indie bookstores or Barnes & Nobles across the country, wherever they have friends/connections, and ask them to buy out books, then they will pay them back,” Sarah told me. “It’s almost always health/wellness and diet book authors. It’s honestly astounding.”

While authors of many genres use these tactics, it’s rare to see a dagger next to your favourite literary novelist’s new book. Typically, it’s nonfiction authors with big names, bigger egos, and the funds needed to blow more than most writers earn on their advances to have “New York Times best-selling author” in their LinkedIn bio.

According to Tracy, “business authors” are among those most likely to do this. “They usually have disposable income since they are high-powered executives at whatever company, and they care less about people actually reading it than being able to say they were a New York Times best seller,” Tracy alleged. “In my opinion, books written by executives are simply tools for building the authors’ brands, landing more high-paying ‘keynotes’ and other ‘thought leadership’ opportunities, and giving a veneer of credibility.”

Notably, Marc Benioff (co-CEO of Salesforce), Stephen Schwarzman (CEO of Blackstone), and Howard Schultz (CEO of Starbucks) all had daggers under their names when their books appeared on the list, though whether any of these three conducted best seller campaigns remains unknown.

Schmidt pointed to Donald Trump Jr. and Jared Kushner as examples of people whose books were reportedly buoyed by massive bulk purchases, referring to an October piece in Forbes that connected a Trump political committee’s purchase of $158,000 in books to Kushner’s 2022 memoir Breaking History. In Trump Jr.’s case, the Times itself reported that the RNC spent nearly $100,000 on copies of his 2019 book Triggered, which, like Kushner’s book, debuted atop the Hardcover Nonfiction list, along with a dagger.

“By allowing bulk purchases to inform a book’s placement on the list, even with a dagger, The New York Times is discounting single purchases of other books that may have hit the list if bulk purchases weren’t allowed to count,” says Schmidt, who’s seen these practices throughout her career. She argues, “This is an inequitable practice by both publishers and The New York Times. If the industry wants to uplift BIPOC and LGBTQ authors, allowing certain authors to game the list isn’t the way to make progress.” When asked for comment by Esquire, Torres, the Times spokesperson, replied, “We believe our methodology provides our readers with the best assessment of which books are broadly selling across the U.S.”

Related: How one man stole $2.9 billion worth of art

The question is: How much does being a New York Times best-selling author really matter? I’d argue that it does matter, and while I could sit here waxing poetically about how legacy institutions don’t need to be our barometer for quality art in a modern society, there are objective benefits that come with making it onto the list.

“While no one who works in the book business believes that the best seller list is neutral or accurate or democratic, they understand its value as a marketing tool,” said Professor McGrath. On the most basic level, best sellers are often displayed on a table at the front of a bookstore and receive selective real estate on e-commerce sites. Best sellers get special graphics on their book jackets and produce big news for publicists to share with book media.

“Initially, the Times best-seller list provided publishers with feedback, but it did not necessarily dictate publication,” McGrath notes. “Now, the best seller list symbolises the way that publishing thinks: It’s an industry driven by data. Decisions about book acquisition and promotion are made with sales figures in mind.”

Being a New York Times best seller also helps in negotiating future book deals, which might not seem like a big thing to a CEO or politician whose book is a vanity project for their larger brand, but it’s a very big deal to writers trying to make a living. There are very few spots up for grabs each week, and every time someone engineers their way into one of them — be it through Book Highlight or more standard practices, like timing bulk buys for speaking opportunities — the author who misses out on it also misses out on store placement, more attention from their publisher, or even a best seller bonus that was written into their contract.

Despite Markus Dohle’s testimony that everything in publishing is random, I can assure you that many parts of the publishing industry are not. Because publishers are in the business of selling as many books as possible, agents and publishers pay attention to who ends up on the best seller list. A list with no bearing on literary merit shouldn’t have to matter, but publishing is a business like any other. Let me put it this way: I’ve never been to a publishing house holiday party where we didn’t hear how many New York Times best sellers our division published that year.

While it’s unlikely that The New York Times is about to release or change its magic formula, consumers do have the power to make more informed choices about the weight they give that weekly ranking, and the books they purchase as a result of it.

In the words of Professor McGrath: “The New York Times list is just as important for what it doesn’t show us: significance. Books that make it onto the list sell a lot of copies, and fast, but that doesn’t mean that they will stand the test of time. They might not be read or remembered in five, ten, fifteen years.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Esquire US